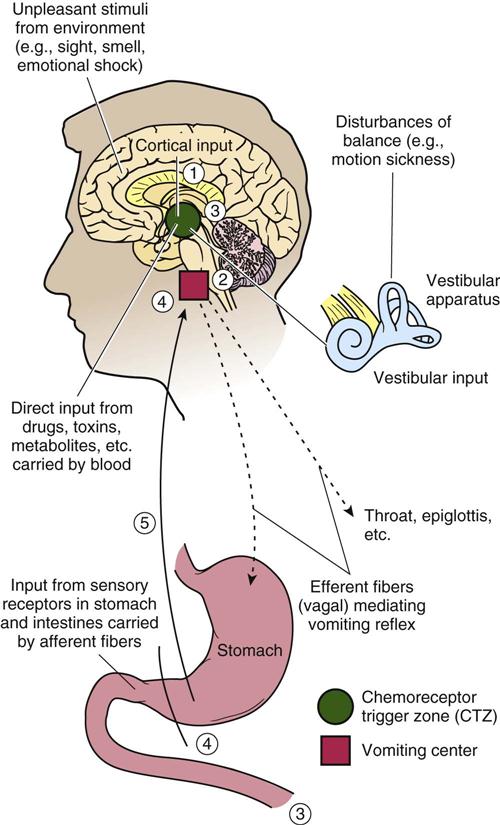

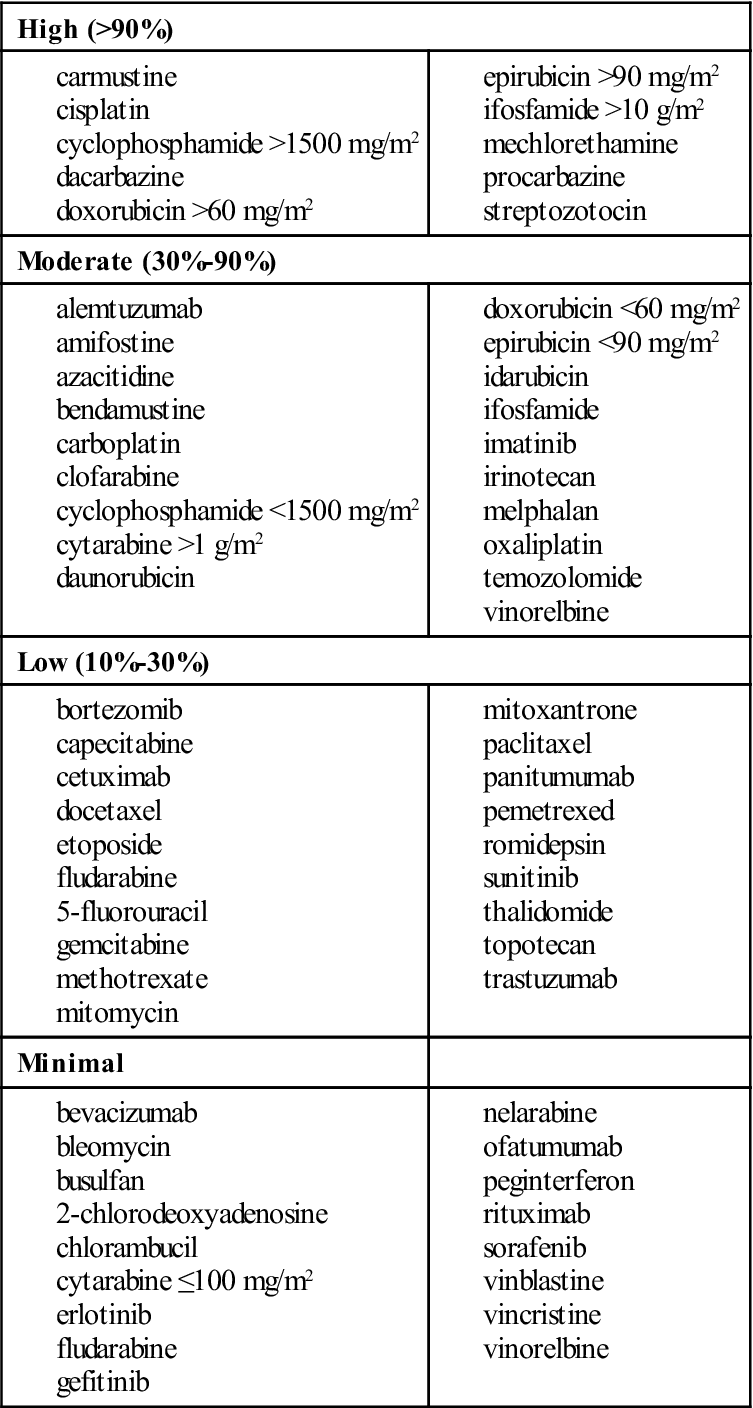

1 Describe the six common causes of nausea and vomiting. 2 Discuss the three types of nausea associated with chemotherapy and the nursing considerations. 3 Identify the therapeutic classes of antiemetics. 4 Discuss the scheduling of antiemetics for maximum benefit. nausea ( vomiting ( emesis ( retching ( regurgitation ( postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) ( hyperemesis gravidarum ( psychogenic vomiting ( chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) ( anticipatory nausea and vomiting ( emetogenicity ( delayed emesis (p. 536) radiation-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV) (p. 536) Nausea is the sensation of abdominal discomfort that is intermittently accompanied by a desire to vomit. Vomiting is the forceful expulsion of gastric contents (emesis) up the esophagus and out the mouth. Nausea may occur without vomiting, and sudden vomiting may occur without prior nausea, but the two symptoms often occur together. Retching is the involuntary labored, spasmodic contractions of the abdominal and respiratory muscles without emesis (also known as “dry heaves”). Nausea and vomiting accompany almost any illness, are experienced by virtually everyone at one time or another, and have a wide variety of causes (Box 34-1). The primary anatomic areas involved in vomiting are shown in Figure 34-1. The vomiting center (VC; more recently referred to as the “central pattern generator”), located in the medulla of the brain, coordinates the vomiting reflex. Nerves from sensory receptors in the pharynx, stomach, intestines, and other tissues connect directly with the VC through the vagus and splanchnic nerves and produce vomiting when stimulated. The VC also responds to stimuli originating in other tissues, such as the cerebral cortex, vestibular apparatus of the inner ear, and blood. These stimuli travel first to the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), which then activates the VC to induce vomiting. The CTZ is also located in the medulla. An important function of the CTZ is to sample blood and spinal fluid for potentially toxic substances and, when detected, to initiate the vomiting reflex. The CTZ cannot initiate vomiting independently, but only by stimulating the VC. Both the VC and the CTZ are much smaller than shown in Figure 34-1. The cerebral cortex of the brain can be a source of stimulus or suppression of the VC (see Figure 34-1). Vomiting can occur as a conditioned response (e.g., see “Anticipatory Nausea and Vomiting,” later in this chapter) or as a reaction to unpleasant sights and smells. Suppression of motion sickness by the person’s concentration on some mental activity is an example of cortical control of the vomiting reflex. Psychological factors can play an important role (see “Psychogenic Vomiting”), although they are usually controlled by physical factors. When the VC is stimulated, nerve impulses are sent to the salivary, vasomotor, and respiratory centers. The vomiting reflex begins with a sudden deep inspiration that increases abdominal pressure, which is further increased by contraction of the abdominal muscles. The soft palate rises and the epiglottis closes, thus preventing aspiration of vomitus into the lungs. The pyloric sphincter contracts and the cardiac sphincter and esophagus relax, allowing stomach contents to be expelled. The flow of saliva increases to aid the expulsion. Autonomic symptoms of pallor, sweating, and tachycardia cause additional discomfort associated with vomiting. Regurgitation occurs when the gastric or esophageal contents rise to the pharynx because of greater pressure (gas bubbles, tight clothing, body position) in the stomach and should not be confused with vomiting. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) constitute a relatively common complication after surgery. The incidence of nausea and vomiting varies with the surgical procedure, gender, age, obesity, anesthetic procedure, and analgesia used. A previous history of motion sickness and PONV also is an indicator of the likelihood of developing this postoperative complication. Factors associated with obesity that may contribute to a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting are a larger residual gastric volume, increased esophageal reflux, and increased risk for gallbladder and gastrointestinal (GI) disease. Fat-soluble anesthetics may also accumulate in adipose tissue and continue to be released long after anesthesia is discontinued. Pain not treated with appropriate analgesia may also induce nausea and vomiting. Surgical procedures that have a higher incidence of PONV are extraocular muscle and middle ear manipulations, testicular traction, and abdominal surgery. Women have a higher incidence of PONV, possibly because of hormonal differences. Children ages 11 to 14 years have the highest incidence based on age group. Patients who have had general anesthesia have a higher incidence of PONV than those who have had regional anesthesia; spinal anesthesia is generally associated with less PONV than general anesthesia, and peripheral regional anesthesia is the least emetogenic. Analgesics (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, alfentanil) used as premedication or with regional anesthetics frequently induce nausea and vomiting. Patients under nitrous oxide anesthesia have a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting than do those under halothane, enflurane, or isoflurane. Swallowed blood and gas accumulation in the stomach may also induce nausea and vomiting. Nausea and vomiting associated with motion are thought to result from stimulation of the labyrinth system of the ear, with subsequent transmission of this stimulus to the vestibular network located near the VC. When there is strong or frequent stimulation, such as from a rocking ship or airplane, the vestibular network is bombarded with an abnormally high number of impulses that radiate by cholinergic nerve impulses to the adjacent VC. Thus, drugs that inhibit the cholinergic nerve impulses from the vestibular network to the VC should be effective in treating motion sickness. The percentage of women reporting vomiting during the first 16 weeks of gestation is relatively constant at about 40%, decreasing to 20% from 17 to 20 weeks; only 9% of women report vomiting after 20 weeks of pregnancy. Vomiting is much more common among primigravidas, younger women, nonsmokers, African Americans, and obese women. Contrary to commonly held beliefs, vomiting is not more common in women who have experienced prior fetal losses or women with hypertension, proteinuria, or diabetes. There is also no association between vomiting and cohabitation; unplanned pregnancy; or gallbladder, liver, or thyroid disease. Although traditionally described as “morning sickness,” most women report that symptoms of nausea and vomiting tend to persist to varying degrees throughout the day. The cause of morning sickness is unknown, but its occurrence and severity appear to be related to the levels of free and bound estradiol and sex hormone–globulin-binding capacity. A woman with severe persistent vomiting that interferes with nutrition, fluid, and electrolyte balance may be experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum, a condition in which starvation, dehydration, and acidosis are superimposed on the vomiting syndrome. Hospitalization for fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional therapy may be required. Psychogenic vomiting can be self-induced, or it can occur involuntarily in response to situations that the person considers threatening or distasteful (e.g., eating food whose origin is considered repulsive). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is the most unpleasant adverse effect associated with the use of cancer chemotherapy. Many patients regard it as the most stressful aspect of their disease, more so even than the prospect of dying. Because the object of cancer therapy is at least to prolong life, the effect of CINV on the quality of life must be considered. Three types of emesis have been identified in patients receiving antineoplastic therapy—anticipatory nausea and vomiting, acute CINV, and delayed emesis. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting is a conditioned response triggered by the sight or smell of the clinic or hospital or by the knowledge that treatment is imminent. The onset of anticipatory nausea and vomiting is usually 2 to 4 hours before treatment and is most severe at the time of chemotherapy administration. Patients who experience anticipatory nausea and vomiting are more likely to be younger and to have received about twice as many courses of chemotherapy, with more drugs, for about three times as long as patients who do not experience this complication. Acute CINV may be stimulated directly by chemotherapeutic agents. These agents have emetogenicity, which refers to having the ability to cause emesis. This type of emesis may begin 1 to 6 hours after chemotherapy has been administered and may last for up to 24 hours. The emetogenicity of antineoplastic drugs is highly variable, ranging from an incidence of almost 100% with high-dose cisplatin to less than 10% with chlorambucil. Table 34-1 summarizes chemotherapeutic agents in terms of emetogenicity. Emetogenicity also is influenced by dosage, duration, and frequency of administration. Table 34-1 Potential of Emesis With Intravenous Antineoplastic Agents* *Estimated incidence without prophylaxis. Data from Roila F, Hesketh PJ, Herrstedt J, et al: Prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced emesis: results of the 2004 Perugia International Antiemetic Consensus Conference, Ann Oncol 17:20-28, 2006; Grunberg SM, Warr D, Gralla RJ, et al. Evaluation of new antiemetic agents and definition of antineoplastic agent emetogenicity—state of the art, Support Care Cancer 19(Suppl 1):S43-S47, 2010. Patient factors also affect acute CINV. The incidence and severity of CINV are generally higher in younger people, women, those in poor general health, and those with metabolic disorders (e.g., uremia, dehydration, infection, GI obstruction). Patients with a history of motion sickness seem to be more sensitive to the emetic effects of cytotoxic agents. The patient’s outlook and attitude about cancer and therapy can significantly influence the frequency and severity of nausea and vomiting. Delayed emesis occurs 24 to 120 hours after the administration of chemotherapy. The mechanisms are not known, but delayed emesis in patients receiving chemotherapy may be induced by metabolic by-products of the chemotherapeutic agent or by destruction of malignant cells. The emesis experienced is usually less severe than that which occurs acutely, but it still can be significant in reducing activity, nutrition, and hydration. Patients who have incomplete control of acute emesis often experience delayed emesis. Events that often trigger delayed nausea and vomiting are brushing teeth, using mouthwash, manipulating dentures, seeing food, and quickly standing up after getting out of bed in the morning. Another common cause of emesis associated with the treatment of cancer is radiation-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV). The use of high-energy radiation (also known as radiotherapy) from x rays, gamma rays, neutrons, and other sources to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors also induces nausea and vomiting, especially when concurrent chemotherapy is used. Radiation may come from a machine outside the body (external beam radiation therapy), or it may come from radioactive material placed in the body near cancer cells (internal radiation therapy, implant radiation). The frequency of RINV depends on the treatment site, field exposure, dose of radiation delivered per fraction, and total dose delivered. Control of vomiting is important for relieving the obvious distress associated with it and preventing aspiration of gastric contents into the lungs, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. Primary treatment of nausea and vomiting should be directed at the underlying cause. Because this is not always possible, treatment with nondrug as well as drug measures is appropriate. Most medicines (antiemetics) used to treat nausea and vomiting act either by suppressing the action of the VC or by inhibiting the impulses going to or coming from the center. These agents are generally more effective if administered before the onset of nausea, rather than after it has started. The seven classes of agents used as antiemetics are dopamine antagonists, serotonin antagonists, anticholinergic agents, corticosteroids, benzodiazepines, neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, and cannabinoids. As noted, there is no single cause of PONV, and therefore treatment with a single pharmacologic agent for all cases is unlikely. Measures such as limiting patient movement and preventing gastric distention can reduce PONV. Adequate analgesia can also forestall this complication. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics are not emetogenic (opioids are emetogenic) and should be given consideration if appropriate to the type of surgical procedure. Antiemetics used include dopamine antagonists, anticholinergic agents, and serotonin antagonists. The histamine-2 (H2) antagonists (e.g., cimetidine, ranitidine) also are occasionally used to reduce gastric secretions to minimize nausea and vomiting. PONV is usually managed with an as-needed (PRN) order, but patients who are considered to be at moderate to high risk for PONV should be considered for prophylactic antiemetic therapy. In addition to minimizing the risk factors listed, a multimodal treatment approach is recommended because of the variety of receptor types associated with PONV. Therapy may include hydration, supplemental oxygen, a benzodiazepine for anxiolysis, a combination of antiemetics that work by different mechanisms (e.g., droperidol, dexamethasone, serotonin antagonist), intravenous (IV) anesthesia induction agents (e.g., propofol and remifentanil), and analgesia with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (e.g., ketorolac) rather than an opioid. Nonpharmacologic techniques prior to surgery using acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and acupressure stimulation have also been shown to reduce PONV. The first step in treating PONV is to identify the cause. If a nasogastric (NG) tube is in place, check its patency and placement in preventing abdominal distention. Do not move an NG tube that was inserted during surgery (e.g., gastric resection); in this case, there is a danger of penetrating the suture line. Irrigation of a blocked NG tube may alleviate the nausea and vomiting. (A health care provider’s order to irrigate the NG tube is required.) Administration of PRN antiemetics when the patient first reports nausea will often prevent vomiting. Most agents used to reduce nausea and vomiting from motion sickness are chemically related to antihistamines. The effectiveness of antihistamines in motion sickness probably results from their anticholinergic properties, not from their ability to block histamine. In most cases, morning sickness can be controlled by dietary measures alone. The woman should be advised to eat small, frequent dry meals and to avoid fatty foods and other foods found to cause problems. Sometimes it may be difficult or impossible to work in the kitchen around food, and assistance may be required. In about 10% to 15% of cases, dietary measures alone will be insufficient and drug therapy should be considered. Drugs that have been widely used for treating morning sickness are vitamin B6, antihistamines (doxylamine, diphenhydramine, dimenhydrinate, meclizine), and phenothiazines such as promethazine and prochlorperazine. Ginger, an herb (see Chapter 48), is used in many cultures to treat pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. From a safety standpoint, vitamin B6 and doxylamine are generally recommended first. If persistent vomiting threatens maternal nutrition, promethazine may be considered. If antidopaminergic antiemetic therapy is required, prochlorperazine is the safest time-tested medicine. Ondansetron and metoclopramide have been shown to be effective antiemetics in treating hyperemesis gravidarum, and no teratogenic effects have been reported to date. When a person has chronic or recurrent vomiting, a diagnosis of psychogenic vomiting is made after eliminating all other possible causes. The person with psychogenic vomiting usually does not lose weight and can control vomiting in certain situations (e.g., in public). Identification of the causes of psychogenic vomiting and successful resolution of the problem may not be possible. After an extensive workup eliminates other potential causes, a short course of an antiemetic drug (e.g., metoclopramide) or antianxiety drug may be prescribed, along with counseling. People with a negative attitude toward therapy, such as the belief that it will be of no benefit, are more likely to develop anticipatory nausea and vomiting. It tends to become more severe as treatments progress unless behavior therapy modifies the conditioned response. Such treatments include progressive muscle relaxation, mind diversion, hypnosis, self-hypnosis, systematic desensitization, music therapy, acupressure, and benzodiazepines (alprazolam, lorazepam). Nurses can play a significant role by maintaining a positive supportive attitude with the patient and making sure that the patient receives antiemetic therapy before each course of chemotherapy. Antiemetic therapy to minimize acute CINV is based on the emetogenic potential of the antineoplastic agents used. Combinations of antiemetics are often used, based on the assumption that antineoplastic agents produce emesis by more than one mechanism. In general, all patients being treated with chemotherapeutic agents of moderate-to-high emetogenic potential should receive prophylactic antiemetic therapy before chemotherapy is started. Combinations of ondansetron, dolasetron, granisetron or palonosetron, dexamethasone, aprepitant, and possibly lorazepam and/or an H2 blocker (e.g., ranitidine) and/or a proton pump inhibitor (e.g., esomeprazole, pantoprazole) are often used. Antiemetic therapy should be continued for 2 to 4 days to prevent delayed vomiting. Emesis induced by moderately emetogenic agents may be treated prophylactically with a similar regimen and therapy should be continued for 24 hours. Dexamethasone with or without a phenothiazine (prochlorperazine) or metoclopramide is recommended if the chemotherapy has low emetic potential. Lorazepam and an H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor (such as cited earlier) may be added to the antiemetic regimen, if necessary. Antiemetic therapy is not recommended with medications with minimum emetic risk, although prochlorperazine may be used to prevent delayed emesis. All antiemetics should be given an adequate amount of time before chemotherapy is initiated and should be continued for an appropriate time after the antineoplastic agent has been discontinued. In general, patients who have complete control of acute emesis have a much lower incidence of delayed-onset emesis. A combination of prochlorperazine, lorazepam, and diphenhydramine given orally 1 hour before meals has successfully controlled delayed emesis. Recent studies have indicated that providing optimal antiemetic therapy with the chemotherapy will significantly reduce the frequency of delayed emesis. Adding aprepitant, the neurokinin-1 (NK1) antagonist, in combination with a serotonin antagonist plus dexamethasone, significantly reduces the incidence of delayed emesis. Clinical guidelines recommend that patients who will be receiving radiation over a large portion of the body or those receiving single-exposure, high-dose radiation therapy to the upper abdomen should receive preventive antiemetic therapy. Granisetron and ondansetron, serotonin antagonists, with or without dexamethasone are approved and recommended to treat RINV. Patients at low to intermediate risk for RINV should receive granisetron, ondansetron, or prochlorperazine before each dose of radiation. Rescue medicines used to treat RINV include prochlorperazine and metoclopramide. Patients who require rescue antiemetic therapy should be pretreated with a serotonin antagonist before the next dose of radiation therapy. Nausea and vomiting are associated with illnesses of the GI tract and other body systems and with adverse effects of medications and food intolerance. Nursing care must be individualized to the patient’s diagnosis and needs at all times. History

Drugs Used to Treat Nausea and Vomiting

Objectives

Key Terms

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 534)

) (p. 535)

) (p. 535)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

) (p. 536)

Nausea and Vomiting

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Common Causes of Nausea and Vomiting

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

Motion Sickness

Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy

Psychogenic Vomiting

Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

Radiation-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

Drug Therapy For Selected Causes of Nausea and Vomiting

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

Motion Sickness

Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy

Psychogenic Vomiting

Anticipatory Nausea and Vomiting

Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

Delayed Emesis

Radiation-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

![]() Nursing Implications for Nausea and Vomiting

Nursing Implications for Nausea and Vomiting

Assessment

34. Drugs Used to Treat Nausea and Vomiting

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree