Theory of comfort

Thérèse Dowd

“In today’s technological world, nursing’s historic mission of providing comfort to patients and family members is even more important. Comfort is an antidote to the stressors inherent in health care situations today, and when comfort is enhanced, patients and families are strengthened for the tasks ahead. In addition, nurses feel more satisfied with the care they are giving”

K. Kolcaba (personal communication, March 7, 2012).

Katharine Kolcaba

1944 to present

Credentials and background of the theorist

Katharine Kolcaba was born and educated in Cleveland, Ohio. In 1965, she received a diploma in nursing and practiced part time for many years in medical-surgical nursing, long-term care, and home care before returning to school. In 1987, she graduated in the first RN to MSN class at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, with a specialty in gerontology. While in school, she job-shared a head nurse position on a dementia unit. It was in this practice context that she began theorizing about the outcome of patient comfort.

Photo credit: Barker’s Camera Shop, Chagrin Falls, OH.

The author wishes to thank Katharine Kolcaba for her assistance with this chapter.

Kolcaba joined the faculty at the University of Akron College of Nursing after graduating with her master’s degree in nursing. She gained and maintains American Nurses Association (ANA) certification in gerontology. She returned to CWRU to pursue her doctorate in nursing on a part-time basis while continuing to teach. Over the next 10 years, she used course work in her doctoral program to develop and explicate her theory. Kolcaba published a concept analysis of comfort with her philosopher-husband (Kolcaba & Kolcaba, 1991), diagrammed aspects of comfort (Kolcaba, 1991), operationalized comfort as an outcome of care (Kolcaba, 1992a), contextualized comfort in a middle-range theory (Kolcaba, 1994), and tested the theory in an intervention study (Kolcaba & Fox, 1999).

Currently, Dr. Kolcaba is an emeritus associate professor of nursing at the University of Akron College of Nursing, where she teaches theory to MSN students. She also teaches theory to DNP students at Ursuline College in Mayfield Heights, Ohio. Her interests include interventions for and documentation of changes in comfort for evidence-based practice. She resides in the Cleveland area with her husband, where she enjoys being near her grandchildren and her mother. She represents her company, known as The Comfort Line, to assist health care agencies implement the Theory of Comfort on an institutional basis. She is founder and coordinator of a local parish nurse program and a member of the ANA. Kolcaba continues to work with students conducting comfort studies.

Theoretical sources

Kolcaba began her theoretical work diagramming her nursing practice early in her doctoral studies. When Kolcaba presented her framework for dementia care (Kolcaba, 1992b), a member of the audience asked, “Have you done a concept analysis of comfort?” Kolcaba replied that she had not but that would be her next step. This question began her long investigation into the concept of comfort.

The first step, the promised concept analysis, began with an extensive review of the literature about comfort from the disciplines of nursing, medicine, psychology, psychiatry, ergonomics, and English (specifically Shakespeare’s use of comfort and the Oxford English Dictionary [OED]). From the OED, Kolcaba learned that the original definition of comfort was “to strengthen greatly.” This definition provided a wonderful rationale for nurses to comfort patients since the patients would do better and the nurses would feel more satisfied.

Historical accounts of comfort in nursing are numerous. Nightingale (1859) exhorted, “It must never be lost sight of what observation is for. It is not for the sake of piling up miscellaneous information or curious facts, but for the sake of saving life and increasing health and comfort” (p. 70).

From 1900 to 1929, comfort was the central goal of nursing and medicine because, through comfort, recovery was achieved (McIlveen & Morse, 1995). The nurse was duty bound to attend to details influencing patient comfort. Aikens (1908) proposed that nothing concerning the comfort of the patient was small enough to ignore. The comfort of patients was the nurse’s first and last consideration. A good nurse made patients comfortable, and the provision of comfort was a primary determining factor of a nurse’s ability and character (Aikens, 1908).

Harmer (1926) stated that nursing care was concerned with providing a “general atmosphere of comfort,” and that personal care of patients included attention to “happiness, comfort, and ease, physical and mental,” in addition to “rest and sleep, nutrition, cleanliness, and elimination” (p. 26). Goodnow (1935) devoted a chapter in her book, The Technique of Nursing, to the patient’s comfort. She wrote, “A nurse is judged always by her ability to make her patient comfortable. Comfort is both physical and mental, and a nurse’s responsibility does not end with physical care” (p. 95). In textbooks dated 1904, 1914, and 1919, emotional comfort was called mental comfort and was achieved mostly by providing physical comfort and modifying the environment for patients (McIlveen & Morse, 1995).

In these examples, comfort is positive and achieved with the help of nurses and, in some cases, indicates improvement from a previous state or condition. Intuitively, comfort is associated with nurturing activity. From its word origins, Kolcaba explicated its strengthening features, and from ergonomics, its direct link to job performance. However, often its meaning is implicit, hidden in context, and ambiguous. The concept varies semantically as a verb, noun, adjective, adverb, process, and outcome.

Kolcaba used ideas from three early nursing theorists to synthesize or derive the types of comfort in the concept analysis (Kolcaba & Kolcaba, 1991).

• Relief was synthesized from the work of Orlando (1961), who posited that nurses relieved the needs expressed by patients.

• Ease was synthesized from the work of Henderson (1966), who described 13 basic functions of human beings to be maintained during care.

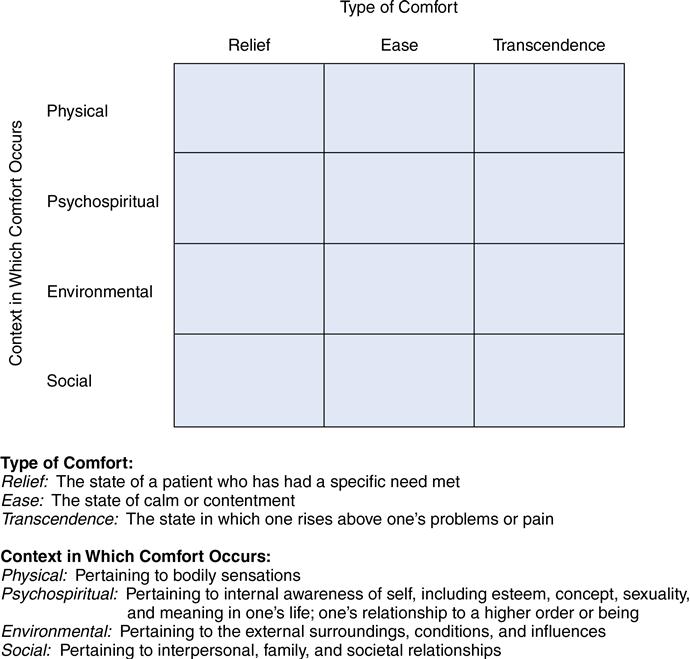

Four contexts of comfort, experienced by those receiving care, came from the review of nursing literature (Kolcaba, 2003). The contexts are physical, psychospiritual, sociocultural, and environmental. The four contexts were juxtaposed with the three types of comfort, creating a taxonomic structure (matrix) from which to consider the complexities of comfort as an outcome (Figure 33–1).

The taxonomic structure provides a map of the content domain of comfort. It is anticipated that researchers will design instruments in the future such as the questionnaire developed from the taxonomy for the end-of-life instrument (Kolcaba, Dowd, Steiner, & Mitzel, 2004). Kolcaba includes the steps on her website for adaptation of the General Comfort Questionnaire by future researchers.

Use of empirical evidence

The seeds of modern inquiry about the outcome of comfort were sown in the late 1980s, marking a period of collective, but separate, awareness about the concept of holistic comfort. Hamilton (1989) made a leap forward by exploring the meaning of comfort from the patient’s perspective. She used interviews to ascertain how each patient in a long-term care facility defined comfort. The theme that emerged most frequently was relief from pain, but patients also identified good position in well-fitting furniture and a feeling of being independent, encouraged, worthwhile, and useful. Hamilton concluded, “The clear message is that comfort is multi-dimensional, meaning different things to different people” (p. 32).

After Kolcaba developed her theory, she demonstrated that changes in comfort could be measured using an experimental design in her dissertation (Kolcaba & Fox, 1999). In this study, health care needs were those (comfort needs) associated with a diagnosis of early breast cancer. The holistic intervention was guided imagery, designed specifically for this patient population to meet their comfort needs, and the desired outcome was their comfort. The findings revealed a significant difference in comfort over time between women receiving guided imagery and the usual care group (Kolcaba & Fox, 1999). Kolcaba and associates conducted additional empirical testing of the Theory of Comfort, which is detailed in her book (Kolcaba, 2003, pp. 113–124) and cited on her website. These comfort studies demonstrated significant differences between treatment and comparison groups on comfort over time. Examples of interventions that have been tested include the following:

• Guided imagery for psychiatric patients (Apóstolo & Kolcaba, 2009)

• Hand massage for hospice patients and long-term care residents (Kolcaba, Dowd, Steiner, & Mitzel, 2004; Kolcaba, Schirm, & Steiner, 2006)

• Patient-controlled heated gowns for reducing anxiety and increasing comfort in preoperative patients (Wagner, Byrne, & Kolcaba, 2006)

In each study, interventions were targeted to all attributes of comfort relevant to the research settings, comfort instruments were adapted from the General Comfort Questionnaire (Kolcaba, 1997, 2003) using the taxonomic structure (TS) of comfort as a guide, and there were at least two (usually three) measurement points used to capture change in comfort over time. The evidence for efficacy of hand massage as an intervention to enhance comfort is published in Evidence-Based Nursing Care Guidelines: Medical-Surgical Interventions (Kolcaba & Mitzel, 2008).

Further support for the Theory of Comfort was found in a study of four theoretical propositions about the nature of holistic comfort (Kolcaba & Steiner, 2000):

1. Comfort is generally state-specific.

2. The outcome of comfort is sensitive to changes over time.

4. Total comfort is greater than the sum of its parts.

Tests on the data set from Kolcaba and Fox’s (1999) earlier study of women with breast cancer supported each proposition. Other areas of study included in the Kolcaba website are burn units, labor and delivery, infertility, nursing homes, home care, chronic pain, pediatrics, oncology, dental hygiene, transport, prisons, deaf patients, and those with mental disabilities.

Major assumptions

Nursing

Nursing is the intentional assessment of comfort needs, the design of comfort interventions to address those needs, and reassessment of comfort levels after implementation compared with a baseline. Assessment and reassessment may be intuitive or subjective or both, such as when a nurse asks if the patient is comfortable, or objective, such as in observations of wound healing, changes in laboratory values, or changes in behavior. Assessment is achieved through the administration of verbal rating scales (clinical) or comfort questionnaires (research), using instruments developed by Kolcaba (2003).

Patient

Recipients of care may be individuals, families, institutions, or communities in need of health care. Nurses may be recipients of enhanced workplace comfort when initiatives to improve working conditions are undertaken, such as those to gain Magnet status (Kolcaba, Tilton, & Drouin, 2006).

Environment

The environment is any aspect of patient, family, or institutional settings that can be manipulated by nurse(s), loved one(s), or the institution to enhance comfort.

Health

Health is optimal functioning of a patient, family, health care provider, or community as defined by the patient or group.

Assumptions

1. Human beings have holistic responses to complex stimuli (Kolcaba, 1994).

2. Comfort is a desirable holistic outcome that is germane to the discipline of nursing (Kolcaba, 1994).

3. Comfort is a basic human need that persons strive to meet or have met. It is an active endeavor (Kolcaba, 1994).

4. Enhanced comfort strengthens patients to engage in health-seeking behaviors of their choice (Kolcaba & Kolcaba 1991; Kolcaba, 1994).

5. Patients who are empowered to actively engage in health-seeking behaviors are satisfied with their health care (Kolcaba, 1997, 2001).

6. Institutional integrity is based on a value system oriented to the recipients of care (Kolcaba 1997, 2001). Of equal importance is an orientation to a health-promoting, holistic setting for families and providers of care.

Theoretical assertions

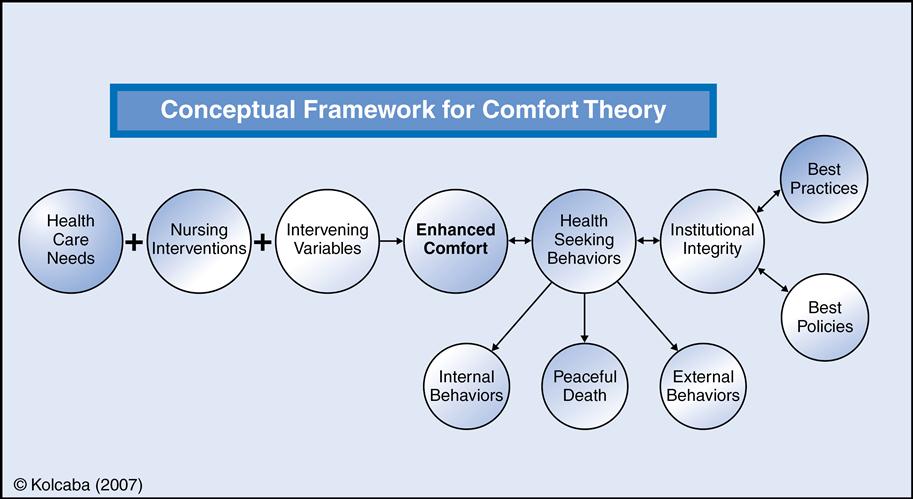

The Theory of Comfort contains three parts (propositional assertions) to be tested separately or as a whole.

Part I states that comforting interventions, when effective, result in increased comfort for recipients (patients and families), compared to a preintervention baseline. Care providers may be considered recipients if the institution makes a commitment to the comfort of their work setting. Comfort interventions address basic human needs, such as rest, homeostasis, therapeutic communication, and treatment as holistic beings. Comfort interventions are usually nontechnical and complement the delivery of technical care.

Part II states that increased comfort of recipients of care results in increased engagement in health-seeking behaviors that are negotiated with the recipients.

Part III states that increased engagement in health-seeking behaviors results in increased quality of care, benefiting the institution and its ability to gather evidence for best practices and best policies.

Kolcaba believes that nurses want to practice comforting care and that it can be easily incorporated with every nursing action. She proposes that this type of comfort practice promotes greater nurse creativity and satisfaction, as well as high patient satisfaction. In order to enhance comfort, the nurse must deliver the appropriate interventions and document the results in the patient record. However, when the appropriate intervention is delivered in an intentional and comforting manner, comfort still may not be enhanced sufficiently. When comfort is not yet enhanced to its fullest, nurses then consider intervening variables to explain why comfort management did not work. Such variables may be abusive homes, lack of financial resources, devastating diagnoses, or cognitive impairments that render the most appropriate interventions and comforting actions ineffective. Comfort management or comforting care includes interventions, comforting actions, the goal of enhanced comfort, and the selection of appropriate health-seeking behaviors by patients, families, and their nurses. Thus, comfort management is proposed to be proactive, energized, intentional, and longed for by recipients of care in all settings. To strengthen the role of nurses as comfort agents, documentation of changes in comfort before and after their interventions is essential. For clinical use, Kolcaba suggests asking patients to rate their comfort from 0 to 10, with 10 being the highest possible comfort in a given health care situation. This documentation could be a part of the electronic data bases in each institution (Kolcaba, Tilton, & Drouin, 2006).

Logical form

Kolcaba (2003) used the following three types of logical reasoning in the development of the Theory of Comfort: (1) induction, (2) deduction, and (3) retroduction (Hardin & Bishop, 2010).

Induction

Induction occurs when generalizations are built from a number of specific observed instances

(Hardin & Bishop, 2010). When nurses are earnest about their practice and earnest about nursing as a discipline, they become familiar with implicit or explicit concepts, terms, propositions, and assumptions that underpin their practice. Nurses in graduate school may be asked to diagram their practice as Dr. Rosemary Ellis asked Kolcaba and other students to do, and it is a deceptively easy-sounding assignment.

Such was the scenario during the late 1980s as Kolcaba began. She was head nurse on an Alzheimer’s unit at the time and knew some of the terms used then to describe the practice of dementia care, such as facilitative environment, excess disabilities, and optimum function. However, when she drew relationships among them, she recognized that the three terms did not fully describe her practice. An important nursing piece was missing, and she pondered about what nurses were doing to prevent excess disabilities (later naming those actions interventions) and how to judge if the interventions were working. Optimum function had been conceptualized as the ability to engage in special activities on the unit, such as setting the table, preparing a salad, or going to a program and sitting through it. These activities made the residents feel good about themselves, as if it were the right activity at the right time. These activities did not happen more than twice a day, because the residents couldn’t tolerate much more than that. What were they doing in the meantime? What behaviors did the staff hope they would exhibit that would indicate an absence of excess disabilities? Should the term excess disabilities be delineated further for clarity?

Partial solutions to these questions were to (1) divide excess disabilities into physical and mental, (2) introduce the concept of comfort to the original diagram, because this word seemed to convey the desired state for patients when they were not engaging in special activities, and (3) note the nonrecursive relationship between comfort and optimum functioning. This thinking marked the first steps toward a theory of comfort and thinking about the complexities of the concept (Kolcaba, 1992a).

Deduction

Deduction occurs when specific conclusions are inferred from general premises or principles; it proceeds from the general to the specific (Hardin & Bishop, 2010). The deductive stage of theory development resulted in relating comfort to other concepts to produce a theory. Since the works of three nursing theorists was entailed in the definition of comfort (Paterson & Zderad, 1975; Henderson, 1966 and Orlando, 1961), Kolcaba looked elsewhere for the common ground needed to unify relief, ease, and transcendence (three major concepts). What was needed was a more abstract and general conceptual framework that was congruent with comfort and contained a manageable number of highly abstract constructs.

The work of psychologist Henry Murray (1938) met the criteria for a framework on which to hang Kolcaba’s nursing concepts. His theory was about human needs; therefore it was applicable to patients who experience multiple stimuli in stressful health care situations. Furthermore, Murray’s idea about unitary trends gave Kolcaba the idea that, although comfort was state-specific, if comforting interventions were implemented over time, the overall comfort of patients could be enhanced over time. In this deductive stage of theory development, she began with abstract, general theoretical construction and used the sociological process of substruction to identify the more specific (less abstract) levels of concepts for nursing practice.

Retroduction

Retroduction is useful for selecting phenomena that can be developed further and tested. This type of reasoning is applied in fields that have few available theories (Hardin & Bishop, 2010). Such was the case with outcomes research, which now is centered on collecting databases for measuring selected outcomes and relating those outcomes to types of nursing, medical, institutional, or community protocols. Murray’s twentieth-century framework could not account for the twenty-first–century emphasis on institutional and community outcomes. Using retroduction, Kolcaba added the concept of institutional integrity to the middle-range Theory of Comfort. Adding the term extended the theory for consideration of relationships between health-seeking behaviors and institutional integrity. In 2007, the concepts of best practices and best policies were linked to institutional integrity. Theory-based evidence organizes the knowledge base for best practices and policies (see Figure 33–2).

Acceptance by the nursing community

Practice

Students and nurse researchers have frequently selected this theory as a guiding framework for their studies in areas such as nurse midwifery (Schuiling, Sampselle, & Kolcaba, 2011), hospice care (Kolcaba, Dowd, Steiner, et al., 2004), perioperative nursing (Wilson & Kolcaba, 2004), long-term care (Kolcaba, Schirm, & Steiner, 2006), stressed college students (Dowd, Kolcaba, Steiner, et al., 2007), dementia patients (Hodgson & Andersen, 2008), and palliative care (Lavoie, Blondeau, & Picard-Morin, 2011).

When nurses ask patients or family members to rate their comfort from 0 to 10 before and after an intervention or at regular intervals, they produce documented evidence that significant comfort work is being done. A verbal rating scale is sensitive to changes in comfort over time (Dowd, Kolcaba, Steiner, et al., 2007). A list of effective comforting interventions for each patient/family member is readily available and communicated.

Perianesthesia nurses have incorporated the Theory of Comfort into their Clinical Practice Guidelines for management of patient comfort. In this setting, comfort management specifies (1) assessing patients’ comfort needs related to current surgery, chronic pain issues, and comorbidities; (2) creating a comfort contract with patients prior to surgery that specifies effective comfort interventions, understandable and efficient comfort measurement, and the type of postsurgical analgesia preferred; (3) facilitating comfortable positioning, body temperature, and other factors related to comfort during surgery; and (4) continuing with comfort management and measurement in the postsurgical period (Wilson & Kolcaba, 2004).

Education

Goodwin, Sener, & Steiner (2007) described guidelines for applying the Theory of Comfort in accelerated baccalaureate nursing programs. The theory proved to be easy for faculty to understand and apply and provided an effective method to role-model a supportive learning partnership with the students. The Theory of Comfort is included in Core Concepts in Advanced Practice Nursing(Robinson & Kish, 2001). The theory is appropriate for students to use in any clinical setting, and its application can be facilitated by use of Comfort Care Plans available on Kolcaba’s website.

Recently, Goodwin, Sener, and Steiner (2007) utilized the Theory of Comfort as a teaching philosophy in a fast-track nursing education program for students with baccalaureate degrees in other disciplines. The taxonomic structure and conceptual framework guided ways of being a comforting faculty member. The theory provided ways for students to obtain relief from their heavy course work by facilitating questions to their clinical problems, maintaining ease with their curriculum through trusting their faculty members, and achieving transcendence from their stressors with use of self-comforting techniques. The authors anticipate “that this adaptation may assist students to transform into professional nurses who are comfortable and comforting in their roles and who are committed to the goal of lifelong learning” (p. 278).

Research

An entry in the Encyclopedia of Nursing Research speaks to the importance of measuring comfort as a nursing-sensitive outcome (Kolcaba, 2006). Nurses can provide evidence to influence decision making at institutional, community, and legislative levels through studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of comforting care. Kolcaba (2001) called for measurement of comfort in large hospitals and home care to expand the theory and develop the literature on evidence-based comfort.

Using the taxonomic structure of comfort (see Figure 33–1) as a guide, Kolcaba (1992a) developed the General Comfort Questionnaire to measure holistic comfort in a sample of hospital and community participants. Positive and negative items were generated for each cell in the taxonomic structure grid. Twenty-four positive items and twenty-four negative items were compiled with a Likert-type format ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, with higher scores indicating higher comfort. At the end of the instrumentation study with 206 one-time participants from all types of units in two hospitals and 50 participants from the community, the General Comfort Questionnaire demonstrated a Cronbach alpha of 0.88 (Kolcaba, 1992a).

Researchers are welcome to generate comfort questionnaires specific to their areas of research. The verbal rating scales and other traditionally formatted questionnaires may be downloaded from Kolcaba’s website, where she also responds to inquiries in an effort to enhance the use of her theory. Instructions for use of the questionnaires are available on her website. Popularity of the theory seems to be associated with universal recognition of comfort as a desirable outcome of nursing care for patients and their families.

Further development

Kolcaba has persisted in the development of her theory from the original conception as the root of her practice, to concept analysis that provided the taxonomic structure of comfort, to development of ways to measure the concept, and currently to its use for practice, education, and research. She uses a full array of approaches to build her theory.

The methodical development of the concept resulted in a strong, clearly organized, and logical theory that is readily applied in many settings for education, practice, and research. Kolcaba developed templates for measurement to facilitate application of the comfort theory in additional settings. The comfort management templates she provided for use in practice settings have been helpful to students and faculty members. Outcomes of research have demonstrated the appropriateness of her theory for measuring whole-person changes that were less effectively captured with other types of instruments, as noted in a study of urinary incontinence (Dowd, Kolcaba, & Steiner, 2000).

The original theoretical assertion (Part 1) of the Theory of Comfort has stood up to empirical testing. When a comfort intervention is targeted to meet the holistic comfort needs of patients in specific health care situations, comfort is enhanced beyond baseline measurement. Furthermore, enhanced comfort has been correlated with engagement in health-seeking behaviors (Schlotfeldt, 1975). Empirical tests of the theoretical assertions for the second and third parts of the theory are to be conducted. Outcomes for desirable health-seeking behaviors could include increased functional status, faster progress during rehabilitation, faster healing, or peaceful death when appropriate. health-seeking behaviors are negotiated among the patient, family members, and care providers. Institutional outcomes would include decreased length of stay for hospitalized patients, smaller number of readmissions, decreased costs, and achievement of national awards such as the Beacon Award. Kolcaba consults with hospital administrators who want to enhance quality of care. She views quality care as comforting actions delivered in an intentional manner in order to create an environment that leads to engagement in health-seeking behaviors.

Kolcaba postulates that intentional emphasis on and support for comfort management by an institution or community increases patient/family satisfaction, because persons are healed, strengthened, and motivated to be healthier. Extending the Theory of Comfort to the community is of current interest. It is well known that some communities are more comfortable to live in, grow old in, and go to school in than are others.

An area of interest for further development is the universal nature of comfort. Currently, the General Comfort Questionnaire has been translated into Taiwanese, Spanish, Iranian, Portuguese, and Italian (see Kolcaba website), and translation into Turkish is pending. Comfort of children has been accurately observed and documented in perioperative settings (personal communication, Nancy Laurelberry, February 16, 2008), and the use of Comfort Daisies by children who self-report (see website) has been tested in a hospital setting (personal communication, Carrie Majka, February 28, 2008).

The Theory of Comfort has been included in electronic nursing classification systems such as NANDA (2011), NIC (2008), and NOC (2008). Kolcaba consults with hospitals to include comfort management in their documentation systems. Use of the theory has made significant contributions to nursing practice and the discipline. Kolcaba continues to spend time and energy developing and disseminating the theory through presentations, publications, and discussions since retirement from full-time teaching.

The Theory of Comfort is widely usedas an organizing framework for Magnet application and recertification of Magnet Status. Nurses often choose this framework themselves because it describes what they want to do for patients and families, and what patients want from nurses during their hospitalization. An array of possible uses of the framework components is offered to the hospital, such as Comfort Rounds, performance review criteria, methods of documentation, clinical ladder criteria, and so on. The “value added” benefit when nurses are supported in their comforting interventions can be empirically demonstrated through measurement of institutional outcomes such as patient satisfaction, “Best Hospital” designations, and cost savings.

Critique

Clarity

Some of the early articles such as the concept analysis (Kolcaba & Kolcaba, 1991) may lack clarity but are consistent in terms of definitions, derivations, assumptions, and propositions. Clarity is much improved in the article explicating the theory and subsequent articles. Kolcaba applies the theory to specific practices using academic, but understandable, language. All research concepts are defined theoretically and operationally.

Simplicity

The Theory of Comfort is simple because it is basic to nursing care and the traditional mission of nursing. Its language and application are of low technology, but this does not preclude its use in highly technological settings. There are few variables in the theory, and selected variables may be used for research or educational projects. The main thrust of the theory is for nurses to return to a practice focused on the holistic needs of patients inside or outside institutional walls. It is simplicity that allows students and nurses to learn and practice the theory easily (Kolcaba, 2003).

Generality

Kolcaba’s theory has been applied in numerous research settings, cultures, and age groups. The only limiting factor for its application is how well nurses and administrators value it to meet the comfort needs of patients. If nurses, institutions, and communities are committed to this type of nursing care, the Theory of Comfort enables efficient, individualized, holistic practice. The taxonomic structure of comfort facilitates researchers’ development of comfort instruments for new settings.

Accessibility

The first part of the theory, asserting that effective nursing interventions offered over time will demonstrate enhanced comfort, has been tested and supported with numerous studies. Furthermore, in the study by Dowd, Kolcaba, & Steiner (2000), enhanced comfort was a strong predictor of increased health-seeking behaviors, meaning when patients are more comfortable, they do better in rehab or recovery. This relationship supports the second and third part of the comfort theory. The comfort instruments have demonstrated strong psychometric properties, supporting the validity of the questionnaires as measures of comfort that reveal changes in comfort over time and support of the taxonomic structure.

Importance

The Theory of Comfort describes patient-centered practice and explains how comfort measures matter to patients, their health, and the viability of institutions. The theory predicts the benefit of effective comfort measures (interventions) for enhancing comfort and engagement in health-seeking behaviors. The Theory of Comfort is dedicated to sustaining nursing by bringing the discipline back to its roots. Documentation of comfort strategies and their effects empirically demonstrates the art of nursing. The outcome of comfort describes the effects of memorable helping interactions with nurses that go beyond checklists or physician orders. It encompasses the art and science of nursing. Making electronic data systems inclusive of value-added outcomes such as comfort is imperative. Collaboration and the openness of Kolcaba’s website facilitates dissemination of the theory for application.

The orientation to patient and family comfort may have been present first in nursing, but it has become invisible and perhaps less valued by a health care system that promotes the use of medications and technology. Refocusing on patient and family comfort represents a return to the roots of nursing and also to the need for empirical evidence. We can demonstrate through research that comfort is foundational to patient recovery, to other health-seeking behaviors, and to institutional viability. The focus is applicable to other health care professions and ancillary workers. The use of a comfort framework implemented throughout a hospital facilitates everyone being “on the same page.”

Summary

From its inception, the Theory of Comfort has focused on what the discipline of nursing does for patients. As the theory evolved, the definition derived from concept analysis expanded to include broader aspects of the patient such as cultural and spiritual aspects. The basic format of the taxonomic structure and conceptual framework remains the same. The development of the General Comfort Questionnaire was important to validate that the concept can be measured and documented, it is positive, and it is related to desirable patient, family, and institutional outcomes.

The theory has relevancy for practice and easily guides nurses in the planning and designing of nursing care in any setting. Its usefulness in education has been described as providing a framework that enables students to organize their assessments and plans of care and learn the art of nursing as well as the science. It is useful for expert nurses in the delivery of care as they demonstrate what they do beyond the technical aspects of nursing.

In research, the theory provides a way to validate improvement in patient comfort after receiving comforting interventions. The concept of comfort accounts for the aspect of quality that the patient describes as “feeling better.” Kolcaba has made consistent efforts to develop and expand comfort into all realms of health care. Through her own thinking and in interaction with nurses and other health professionals, the concept has continually evolved into patient and nurse care techniques. Institutions have recognized the value of designing comfort environments for both their patients and their staff. Through Kolcaba’s publications and Internet activities (website), the Theory of Comfort is now worldwide.