The Child with an Emotional or Behavioral Condition

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

3. Discuss the impact of early childhood experience on a person’s adult life.

4. Discuss the effect of childhood autism on growth and development.

6. List the symptoms of potential suicide in children and adolescents.

7. Discuss immediate and long-range plans for the suicidal patient.

8. List four behaviors that may indicate substance abuse.

9. Name two programs for members of families of alcoholics.

10. Discuss the problems facing children of alcoholics.

11. List four symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

13. Compare and contrast the characteristics of bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa.

Key Terms

art therapy (p. 748)

behavior modification (p. 748)

bibliotherapy (p. 748)

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision) (DSM-IV-TR) (p. 747)

dysfunctional (p. 748)

family therapy (p. 748)

intervention (p. 748)

milieu therapy (mēl-yoo THĔR-ă-pē, p. 748)

play therapy (p. 748)

psychosomatic (sī-kō-sō-MĂ-tĭk, p. 748)

recreation therapy (p. 748)

sibling rivalry (p. 758)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

The Nurse’s Role

The nurse is often the person who has the greatest amount of contact with the family. Assessing child-parent relations is an important and ongoing aspect of care. To work effectively with the disturbed child, nurses first must understand the types of behavior considered within normal range. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision) (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) is a resource that defines mental disorders and is used by health professionals to aid in diagnoses of specific mental health conditions. Nurses are valuable members of the multidisciplinary health care team in that they work closely with hospitalized acutely ill children, long-term chronically ill children, and children in school. Nurses should keep a careful record of behavior and note relationships with members of the family. Such notations are meaningful to the physician and other staff members, who are as concerned with prevention of problems as they are with treating them.

Every day, everywhere, children are trying to cope with stress. Many succeed and grow stronger; some do not. Early childhood intervention programs are helpful in preventing major problems that affect growth and development. Parenting classes teach what to expect at various ages and stages. They also stress the importance of age-appropriate discipline and guidance. Parent groups provide education, socialization, and support. Other agencies provide a variety of services. Some services include the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI), Family Service Association of America, Toughlove, and Youth Suicide National Center. Nurses must be aware of such resources to guide parents appropriately.

When parents request guidance, the nurse encourages them to seek help from their family physician or pediatrician or from a community mental health center. In the hospital, a psychiatric clinical nurse specialist (CNS) is an excellent resource. If the child is in school, the services of the school psychologist or guidance counselor may prove valuable. Some religious centers employ counselors who are available free of charge to parishioners. Families who lack adequate financial resources can be directed to the appropriate agencies. Some agencies not only provide emergency funds but also can establish a budgeting system for those receiving minimum wages. This is particularly helpful when the parents are young adolescents.

No matter how dysfunctional the parent-child relationship, most children consciously and unconsciously identify with parental values. Discrediting of the parents’ values by the health care provider threatens the child’s security and creates anxiety. The nurse reassures parents and helps them regain or maintain confidence in their parenting role. In addition, because children do not seek treatment on their own, the nurse should assist parents in becoming invested in the treatment modality. Finally, as a professional, the nurse supports organizations concerned with mental health, votes on issues that are pertinent to the welfare of children in the community, and offers services when needed.

Types and Settings of Treatment

The basic staff of the modern child guidance clinic is composed of a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, a pediatrician, and the nurse. Usually the child guidance clinic provides diagnostic and treatment services. It may be part of a hospital, school, court, or public health or welfare service, or it may be an independent agency.

The psychiatrist is a medical doctor who specializes in mental disorders. The psychoanalyst is usually a psychiatrist but may be a psychologist; all psychoanalysts have advanced training in psychoanalytic theory and practice. The clinical psychologist has an advanced degree in clinical psychology from a recognized university. Many of these specialists work in the school system with children, teachers, and families to prevent or resolve problems. A counselor is a professional with a master’s degree from an accredited institution. Many counselors specialize in a specific area, such as substance abuse or counseling of children. In most states, counselors must be licensed.

Children who do not respond well to individual outpatient therapy may require the type of care provided in residential treatment centers. Their home situations may be so disruptive that they might benefit from a change of environment. This alternative also provides a cooling-down period for the family. Family therapy is begun and includes all family members. The length of stay for the child varies from 1 to 3 weeks. Partial hospitalization programs in which the child attends therapy during the day and returns home at night are popular.

Intervention may involve individual, family, or group therapy; behavior modification; or milieu therapy. It may also involve a combination of these therapies. Behavior modification focuses on modifying specific behaviors by means of stimulus and response conditioning. Milieu therapy refers to the physical and social environment provided for the child. Art therapy, music therapy, and play therapy are particularly helpful in dealing with younger children who have difficulty expressing themselves. Recreation therapy is also valuable. Bibliotherapy, the reading of stories about children in a situation similar to the child’s situation, is also therapeutic. Creating an emotionally safe environment is basic to all forms of therapy.

Origins of Emotional and Behavioral Conditions

Early childhood experiences are critical to personality formation. Situations that disrupt family patterns can have a lasting impact on the child. Children who come from these dysfunctional families may experience any of the following: failure to develop a sense of trust (in their caregivers and environment), excessive fears, misdirected anger manifested as behavioral problems, depression, low self-esteem, lack of confidence, and feelings of lack of control over themselves and their environment. These and other manifestations may make children feel negative about themselves and the world. They experience guilt and may blame themselves when confronted with disappointment and failure.

Growing up can be painful even under the best circumstances. It is difficult for the child in the early school years to live up to so many rapidly developing standards. Guilt and anxiety develop. Finger sucking, nail biting, excessive fears, stuttering, and conduct problems are reflections of nervous tension.

The current trend toward prevention by identifying risk factors and advocating early intervention is a major goal of children’s mental health services. The term psychosomatic has come to refer to the dysfunctions of the body that seem to have an emotional or a mental basis. Each person has a different potential for coping with life. Truancy, lying, stealing, failure in school, and a crisis such as death or divorce of parents are but a few of the difficulties that may necessitate intervention. Box 33-1 summarizes some of the disorders that can affect behavior and appear during infancy, childhood, and adolescence. Some behavioral disorders are caused by genetic factors; for example, autism is thought to have autosomal recessive inheritance.

Organic Behavioral Disorders

Childhood Autism

Autism is a developmental disorder manifested by motor-sensory, cognitive, and behavioral dysfunctions. It involves impaired social interaction, communication, and interests. Autism refers to one of five disorders defined in the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) as a development disorder, autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and others such as Rett syndrome and disintegrative disorder (APA, 2000). It is often referred to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Cole, 2009). It may be caused by a defect in neurogenesis in the early weeks of fetal life, occurs in 6.69 per 1,000 children, and is more common in males.

Lack of pointing or gesturing at an early age, failure to make eye contact and look at others, poor attention behavior, poor orientation to one’s name, and repetitive behaviors are significant signs of dysfunction by 1 year of age. Research has shown that cognitive delays do not always occur. Peer-related social behavior normally develops early in the preschool period, with symbolic play normally emerging by 2 years of age. Autistic children do not show interest in other children and have difficulty engaging in pretend play. Solitary play is the preference of the autistic child.

Early identification and intervention may help the autistic child. The nurse who is alert to dysfunctions in the social behavior of young children can facilitate early referral, which may result in more meaningful social advances for the autistic child. A checklist for autism in toddlers (CHAT) can be done at 18 months of age. Many sources of information and assessment questionnaires are available online (see Online Resources at the end of the chapter). Treatment of autism involves providing well-structured home and school environments, behavior modification, and in some cases the use of specific drugs to deal with specific behavioral problems. The goal of therapy is to maximize ability to live independently.

Drug therapy of autism is not curative. Haloperidol calms the child without sedating, but it offers no help with learning abilities. Stimulants such as amphetamines decrease hyperactivity, but they impair cognition and may increase self-injurious behavior. A multidisciplinary approach to care is essential. The nurse’s role is to identify abnormal behavior as early as possible, refer for follow-up care, and monitor the side effects of prescribed medications.

The nurse’s approach to the patient should be slow paced, with few distractions. The child should be allowed to become familiar with the office, room, or equipment. Permission should be asked of the child before touching him or her, and sudden movements or loud noise should be avoided. Safety and family support are priorities. The development of meaningful language by 5 years of age is a favorable prognosis, although most autistic children require long-term care.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders in Children

With obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a recurrent, persistent, repetitive thought invades the conscious mind (obsession), or a ritual movement or activity (not related to adapting to the environment) assumes inordinate importance (compulsion). The rituals or movements may involve touching an object, saying a certain word, or washing the hands repetitively. OCD in children differs from OCD in adults in that the symptoms are not usually part of an obsessive personality. The behavior may start as early as 4 years of age but may not be noticed as interfering with daily functioning until 10 years of age or older. Children usually are aware of their compulsive behavior and may voluntarily control themselves while in school with peers. Untreated, the problem grows to interfere with total functioning. OCD is related to depression and other psychiatric disorders such as Tourette’s syndrome; suicidal behavior is a high risk for adolescents with OCD.

OCD does not involve an impairment of cognitive function or interpersonal relationships. OCD has a genetic origin. Some research studies show involvement of the basal ganglia of the frontal lobe and a problem with the neurohormonal system. Children often become withdrawn and isolated from their peers and family. Poor school performance is related to compulsive repetitive behavior rather than a deficit in intelligence. Family conflicts arise to compound the problem. Clomipramine is one medication used to control behavior. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine alter serotonin uptake and are effective for OCD problems.

Behavior therapy combined with medication provides the best results. The treatment involves exposure to the stressor or obsession and prevention of the compulsory response. For behavior therapy to be successful, however, the child must be motivated and capable of following directions. Parent and sibling involvement and support are essential. The nurse’s role is to assess normal growth and development and understand that ritualistic behavior that is normal at 3 years of age is normally replaced by hobbies of collecting and special interests by 8 years of age. Prolonged ritualistic behavior should be referred for follow-up care. Assessing the response to and side effects of medications used to treat OCD is an important nursing role.

Environmental or Biochemical Behavioral Disorders

Depression

Depression in a child is not as easy to identify as depression in an adult. Many children have difficulty expressing their feelings and often “act out” their concerns. Depression is an emotion common to childhood. Sadness caused by receiving poor grades, moving to a new community, or losing a pet may trigger a depressive mood that results in either a dependent type or a disruptive type of behavior. These manifestations are resolved in a short time and are considered perfectly normal.

A major depressive or mood disorder is usually characterized by a prolonged behavioral change from baseline that interferes with schooling, family life, and/or age-specific activities. Symptoms can include loss of appetite, sleep problems, lethargy, social withdrawal, and sudden drop in grades. In young children, head banging, truancy, lying, and stealing can occur. If left untreated, depressive behavior can lead to substance abuse and/or suicide. Inheritance factors, organic factors, and environmental factors all contribute to major depressive disorders in children. Treatment of depressive disorders is often on an outpatient basis and may include prescribed drugs.

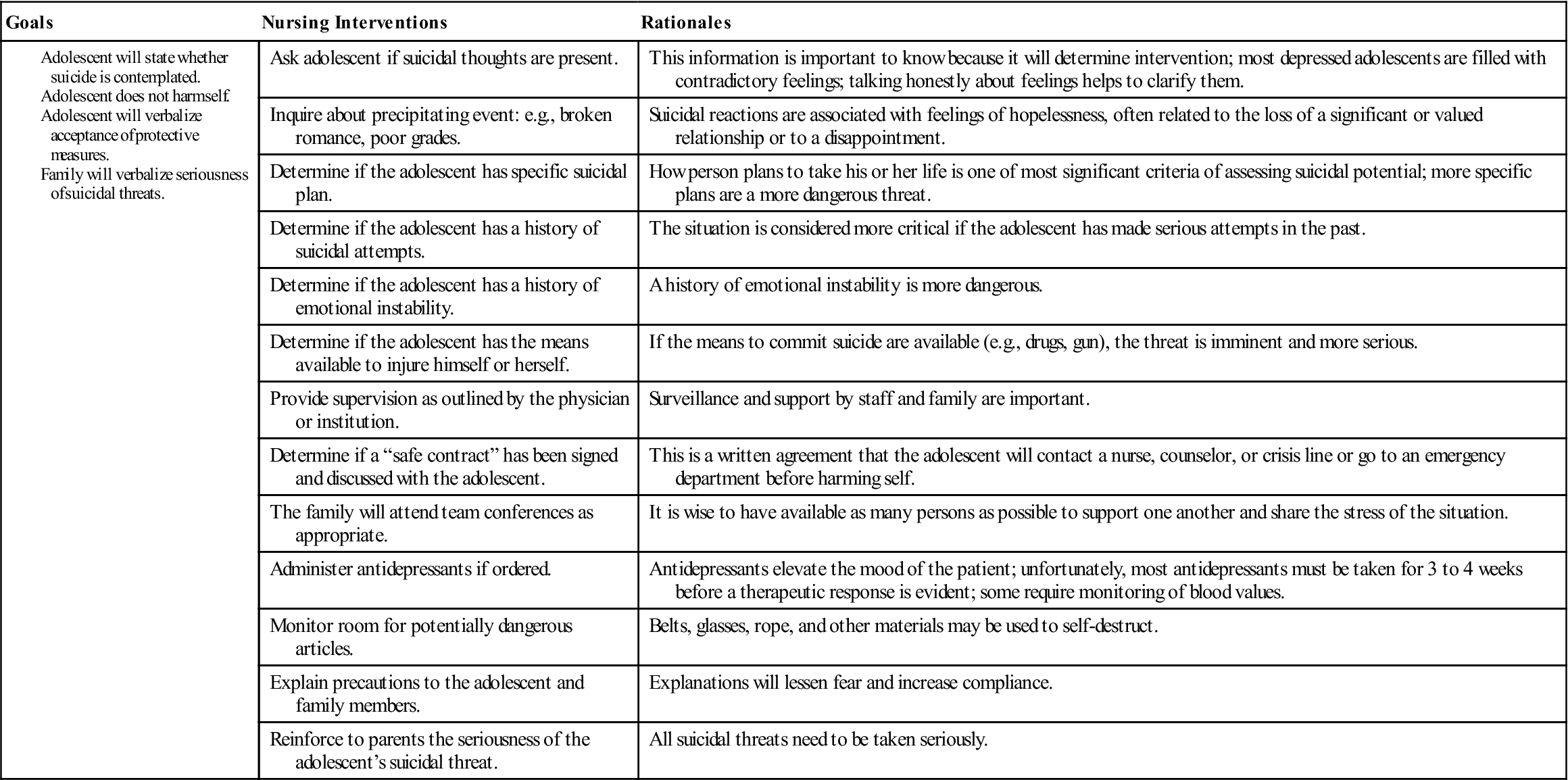

Nursing responsibilities include recognizing the signs of depression and initiating appropriate and prompt referral (Nursing Care Plan 33-1). Educating parents and school personnel concerning the identification of children at risk is an important nursing function in the community and in the hospital setting.