The School-Age Child

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

3. Discuss how to assist parents in preparing a child for school.

4. List two ways in which school life influences the growing child.

5. Contrast two major theoretical viewpoints of personality development during the school years.

6. Discuss accident prevention in this age-group.

Key Terms

androgynous (ăn-DRŎJ-ĭ-nŭs, p. 437)

concrete operations (p. 435)

latchkey children (p. 440)

preadolescent (prē-ăd-ō-LĔS-ĕnt, p. 443)

Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) (p. 437)

sexual latency (p. 435)

stage of industry (p. 435)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

General Characteristics

School-age children (6 to 12 years of age) differ from preschool children in that they are more engrossed in fact than in fantasy and are capable of more sophisticated reasoning. School-age children develop their first close peer relationships outside of the family group and their first affiliation with adults outside of their family who will influence their lives in a significant way.

As a result of the increased contact with the world outside and increased cognitive abilities, school-age children begin to understand how others evaluate them. School-age children are often judged by their performance—good grades or athletic feats. Their sense of industry and the development of a positive self-esteem are directly influenced by their ability to become an accepted member of a peer group and meet the challenges in the environment.

The school-age child must be able to pay attention in class (with at least a 45-minute attention span), understand language, and progress from the skill of writing or reading to understanding what is written or read. To be successful in school, the child must work toward a delayed reward and must risk being unsuccessful in his or her efforts. However, parents must be guided to understand that multiple unsuccessful experiences for their child can lead to the development of a fear of trying in the future. New experiences for the school-age child include the first night sleeping away from home at a friend’s house or camp, successes that are formally celebrated, chores that are dependably performed, conflict resolution with peers, and the selection of adult role models.

School-age children have an ardent thirst for knowledge and accomplishment. They tend to admire their teachers and adult companions. They use the skill and knowledge they obtain to attempt to master the activities they enjoy, including music, sports, and art. Thus this phase is referred to by Erikson as the stage of industry. Unsuccessful adaptations at this time can lead to a sense of inferiority. Participation in group activities heightens. Romantic love for the parent of the opposite sex diminishes, and children identify with the parent of the same sex. Freud refers to this period as a time of sexual latency. The type of acceptance school-age children receive at home and at school will affect the attitudes they develop about themselves and their role in life. Piaget refers to the thought processes of this period as concrete operations.

Concrete operations involves logical thinking and an understanding of cause and effect. The egocentric view of the preschool child is replaced by the ability to understand the point of view of another person. The child can understand the origin or consequence of an event he or she is experiencing. By 10 years of age, the child understands that people do not always control events in life, such as death, spirituality, or the origin of the world (Box 19-1).

Between 6 and 12 years of age, children prefer friends of their own sex and usually prefer the company of their friends to that of their brothers and sisters. Outward displays of affection by adults are embarrassing to them. Although they are now too big to cuddle on their parents’ laps, they still require much love, support, and guidance.

Between 6 and 12 years of age, self-esteem becomes very important in the developmental process. Children are evaluated according to their social contribution, such as the ability to attain good grades, hit home runs or earn a “yellow belt” in Karate class (Figure 19-1). Children’s feelings about themselves are very important and should be assessed.

Physical Growth

Growth is slow until the spurt directly before puberty. Weight gains are more rapid than increases in height. The average gain in weight per year is about 2.5 to 3.2 kg (5.5 to 7 lb). The average increase in height is approximately 5.0 cm (2 inches). Growth in head circumference is slower than before, because myelinization within the brain is complete by 7 years of age. Head circumference increases from 20 to 21 inches between 5 and 12 years of age. At the end of this time, the brain has reached approximately adult size. (Dentition and nutrition are discussed in Chapter 15.)

Muscular coordination is improved, and the lymphatic tissues become highly developed. The skeletal bones continue to ossify, and the body has a lower center of gravity. The body is supple, and sometimes skeletal growth is more rapid than growth of muscles and ligaments. The child may appear “gangling.” There is a noticeable change in facial structures as the jaw lengthens. The sinuses are often sites of infection. The 6-year molars (the first permanent teeth) erupt. The loss of primary teeth begins at about age 6 years, and about four permanent teeth erupt per year. The gastrointestinal tract is more mature, and the stomach is upset less often. Stomach capacity increases, and caloric needs are less than in preschool years. The heart grows slowly and is now smaller in proportion to body size than at any other time of life.

The shape of the eye changes with growth. The exact age at which 20/20 vision occurs, once believed to be about 7 years of age, is now believed to be sometime during the preschool years. The capabilities of the child’s sense organs, including hearing, have an important bearing on learning abilities.

The vital signs of the child of school age are near those of the adult. The temperature is 37° C (98.6° F), the pulse is 85 to 100 beats/min, and respirations are 18 to 20 breaths/min. The systolic blood pressure ranges from 90 to 108 mm Hg; the diastolic blood pressure ranges from 60 to 68 mm Hg. Boys are slightly taller and somewhat heavier than girls until changes indicating puberty appear. The differences among children are greater at the end of middle childhood than at the beginning.

The changes in body proportions help the child prepare for activities commonly enjoyed in school. However, size is not correlated with emotional maturity, and a problem is created when a child faces higher expectations because he or she is taller and heavier than peers. Sedentary activities and habits in the school-age child are associated with a high risk of developing obesity and cardiovascular problems later in life.

Sexual Development

Gender Identity

The sex organs remain immature during the school-age years, but interest in gender differences progresses to puberty. Gender role development is greatly influenced by parents through differential treatment and identification. These two interdependent processes are at work in the family and in society. In infancy, boys and girls are often wrapped in pink or blue blankets. Later, their dress, the types of toys and games chosen for them, television, and the attitudes of family members may serve to fortify gender identity, although unisex dress and play are currently popular.

The influence of the school environment is considerable. The teacher can directly foster stereotyping in the assignment of schoolroom tasks, the choice of textbooks, and the disapproval of behavior that deviates from the child’s gender role. Aggressive behavior is sometimes overlooked in boys but is discouraged in girls.

Some adults develop a gender role concept that incorporates both masculine and feminine qualities, sometimes termed androgynous. Because healthy interpersonal relationships depend on both assertiveness and sensitivity, the incorporation both of traditionally masculine and traditionally feminine positive attributes may lead to fuller human functioning.

Sex Education

Sex education is a lifelong process. Parents convey their attitudes and feelings about all aspects of life, including sexuality, to the growing child. Sex education is accomplished less by talking or formal instruction than by the whole climate of the home, particularly the respect shown to each family member.

Children’s questions about sex should be answered simply and at their level of understanding. Correct names should be used to describe the genitalia. The hospitalized child who complains, “My penis hurts,” is understood by all. Private masturbation is normal and is practiced by both males and females at various times throughout their lives. It does not cause acne, blindness, insanity, or impotence. The young boy must be prepared for erections and nocturnal emissions (“wet dreams”), which are to be expected and are not necessarily the result of masturbation. The young girl is prepared for menarche and is provided with the necessary supplies. This is particularly important to the early maturer because an elementary school may not provide dispensing machines in the restrooms. (See the discussion of the menstrual cycle in Chapter 2.)

Both sexes are concerned during the school years with the disproportion of their bodies, and they may be self-conscious when undressing. They may compare themselves with their friends. They need reassurance about their awakening sexuality, which affects their thoughts and behavior.

Factual knowledge concerning sex and drugs is an essential component of sex education both in the home and at school. School nurses can assist in preparing sex education programs, but participation of parents is valuable. Sex education can be taught in the context of the normal process and function of the human body. Facts must be provided. Values clarification can be added and influenced by parents in the home. If children realize that their parents are uncomfortable with discussing the subject, they may turn to peers, who often supply erroneous and distorted information. The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) maintains that every sex education program should present the topic from six aspects: biological, social, health, personal adjustment and attitudes, interpersonal associations, and establishment of values.

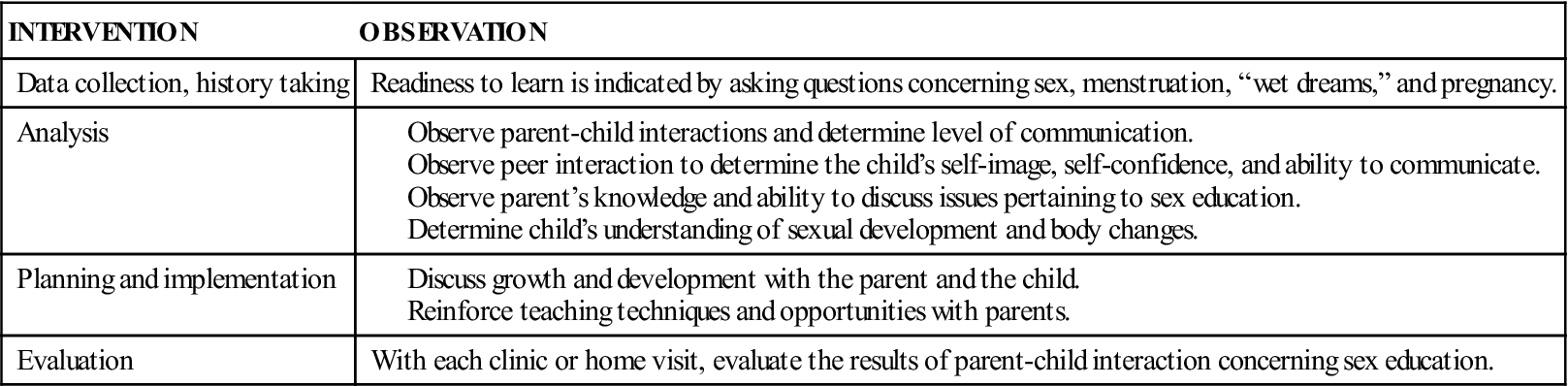

Regardless of the practice setting, nurses can help parents and children with sex education through careful listening and anticipatory guidance (Table 19-1). They can teach decision-making skills and responsibility. Nurses should review normal developmental behavior and explain age-specific information. They provide families with useful written information that stresses sexuality as a healthful rather than as an illness-related concept. The nurse should always consider cultural differences when counseling.

Table 19-1

Using the Nursing Process in Sex Education of the School-Age Child

Sexually Transmitted Infections.

Education concerning sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention should be presented in simple terms. The school nurse is a vital link in the education of the child and the parents. There are audiovisual materials designed for the school-age child. Factual information about STIs and concrete information on how to say “no” to sexual intercourse and drugs is an essential component in the sex education of the preadolescent. The nurse can help to implement educational programs in the school, the clinic, the church, and other community organizations. The facts concerning the harmful effects of drugs and unprotected sex should be communicated to the child without using scare tactics.

Influences from the Wider World

School-Related Tasks

The home, the school, and the neighborhood each have an impact on the growth and development of the child. Schools have a profound influence on the socialization of children, who bring to school what they have learned and experienced in the home. Although some children come from healthy, intact, and financially secure families, many do not. A child may be disabled or abused or may suffer from a chronic illness. Parents may be alcoholics, substance abusers, unemployed, or suffering from numerous other physical or stress-related conditions. Nurses must remember these factors, because they surface continually with this age-group. Moral development occurs as they have experience with, and understand, rules and fairness. The understanding of what is right and what is wrong and the development of values occurs as a result of their experience.

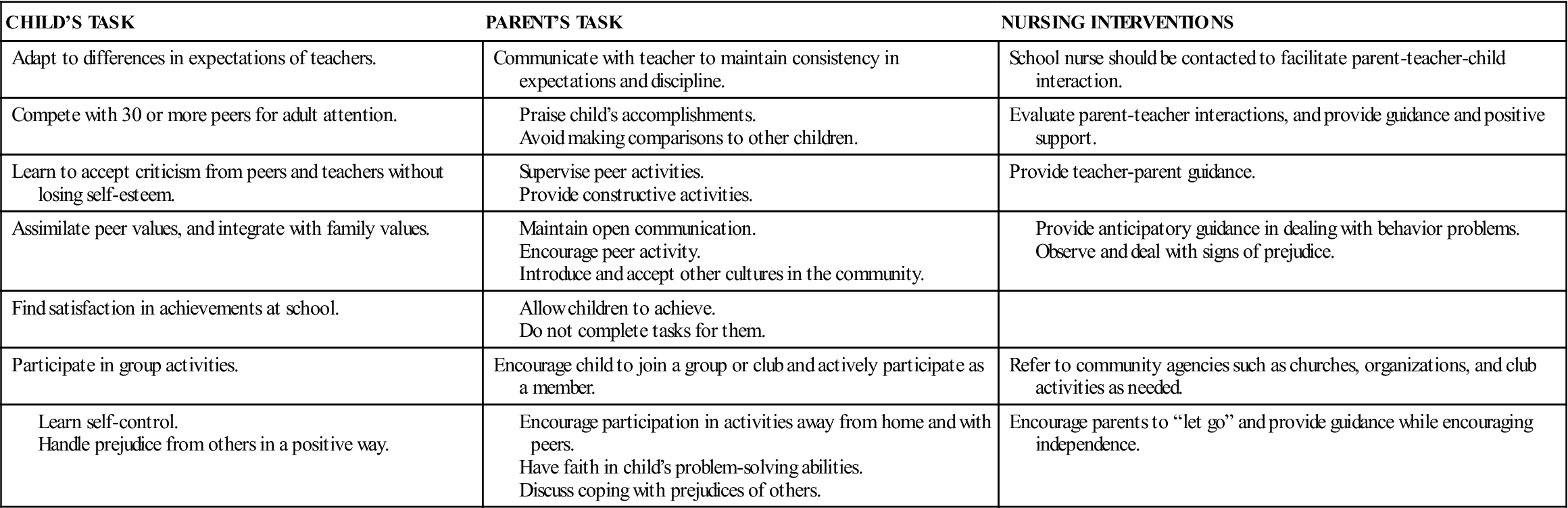

Children may be unable to verbalize their needs; therefore caretakers must become particularly astute in their observations. Table 19-2 reviews the expected growth and development abilities related to required school tasks. Success in school requires an integration of cognitive, receptive, and expressive (language) skills. Repeating a grade in school can seriously impair self-image, and therefore it is important to identify deficits or health problems that affect learning as early as possible.

Table 19-2

Growth and Development of the School-Age Child in School-Related Tasks

A holistic attitude of child care must focus not only on intellectual achievement and test scores but also on such qualities as artistic expression, creativity, joy, cooperation, responsibility, industry, love, and other attributes. The sensitive nurse can assist parents by affirming the individuality of children and by encouraging parents to share with their children the pride they are experiencing as the children learn and progress through the elementary grades. The Patient Teaching box summarizes parental guidance that the nurse may find useful in preparing children for the beginning of school.

The nurse observes patterns of communication between parents and child and assists with specific behavioral problems. In general, the transition to junior high school or “middle school” means multiple classrooms, a series of teachers, and a change of buildings. The child is developing adult characteristics and has new feelings about his or her body, parents, teachers, and peers. Anticipatory guidance includes a review of normal physiology and how it changes with puberty. Information concerning sexuality is reviewed, and the child is encouraged to ask questions at the time they arise.

A warm, ongoing relationship between the parents and child helps to provide a safe atmosphere of caring. Adults should develop a heightened awareness for things such as school attendance problems, tardiness, and signs of loneliness or depression. They should continue to encourage children to discuss their school problems, feelings, and worries. Parents and children must set realistic goals. A good question for adults to contemplate periodically is, “When was the last time this child had a success?” Homework should be the child’s responsibility, with a minimum of assistance from parents. For some children, visits to the nurse’s office may be their only continuous contact with a health care worker. The nurse may be instrumental in establishing positive health patterns that may be carried into adulthood.

The school nurse can guide the parents in determining health care requirements for the school-age child. Schools provide some health screening, but the financial resources of the family may prevent adequate follow-up care, clothing, or transportation. School lunch programs are available in most schools for the child identified as being in need.

Safety is an important issue for the school-age child. The rules of the road should be taught before the child walks or rides a bike to school. Car safety and the use of seat belts must be a regular ritual. Caution in play is essential, but a child must not be made to feel afraid to try new activities or skills.

Play

Play activities in the school-age child involve increased physical and intellectual skills and some fantasy. The sense of belonging to a group is very important, and conformity to “be just like my friends” is of vital importance to the child. The culture of the school-age child involves membership in a group of some type. If parents do not provide a club, scout, or church group, the child may find a group of his or her own, which may be a gang.

Teams are important to growth and development, and competition is a new challenge. Rituals such as collecting items and playing board games are enjoyable quiet activities for the school-age child. Television is often considered to be a “baby-sitter” when overused, but many educational and exciting programs are offered during prime-time hours. Computer and video games challenge intellect and skill and are healthy outlets as long as they do not completely replace active physical play. Play enables the child to feel powerful and in control. Mastering new skills helps the child to feel a sense of accomplishment, which is necessary to successfully achieve Erikson’s phase of industry (Figure 19-2). Participation in organized sports can develop skill, teamwork, and fitness, but excessive pressure and unrealistic expectations can have negative effects. High-stress and high-impact sports such as football are not desirable sports activities for the school-age child because of the risk of injury to the immature skeletal system.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree