The Child with a Communicable Disease

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Interpret the detection and prevention of common childhood communicable diseases.

3. Discuss the characteristics of common childhood communicable diseases.

5. Discuss national and international immunization programs.

6. Describe the nurse’s role in the immunization of children.

7. Demonstrate a teaching plan for preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in an adolescent.

8. Formulate a nursing care plan for a child with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Key Terms

acquired immunity (p. 732)

active immunity (p. 732)

body substance (p. 731)

communicable disease (kŏ-MYŪ-nĭ-kă-būl dĭ-ZĒZ, p. 731)

endemic (ĕn-DĔM-ĭk, p. 731)

epidemic (ĕp-ĭ-DĔM-ĭk, p. 731)

erythema (ĕr-ĭ-THĒ-mă, p. 734)

fomite (FŌ-mīt, p. 731)

health care–associated infection (p. 732)

incubation period (p. 731)

macule (MĂK-yūl, p. 734)

natural immunity (p. 732)

opportunistic infections (ŏp-pŏr-tū-NĬS-tĭk ĭn-FĔK-shŭnz, p. 732)

pandemic (păn-DĔM-ĭk, p. 731)

papule (PĂP-yūl, p. 734)

passive immunity (p. 732)

pathogens (PĂTH-ō-jĕnz, p. 731)

pathognomonic (păth-ŏg-nō-MŎN-ĭk, p. 734)

portal of entry (p. 731)

portal of exit (p. 731)

prodromal period (prō-DRŌ-mŭl PĒ-rē-ŏd, p. 731)

pustule (PŬS-tyūl, p. 734)

reservoir for infection (p. 731)

scab (p. 734)

standard precautions (p. 733)

transmission-based precautions (p. 733)

vector (VĔK-tŭr, p. 731)

vesicle (VĔS-ĭ-kŭl, p. 734)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

There have been only a few brief periods in history when infectious disease did not dominate the attention of health care professionals. Despite immunization, sanitation, antimicrobial drugs, and other controls, the world continues to face infectious agents such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Despite our knowledge of immunizations, some children still suffer from common communicable diseases. Antimicrobial drug-resistant organisms are increasing in number and virulence, and immunocompromised patients are threatened by nonpathogenic organisms. Prevention and control are key factors in managing infectious disease.

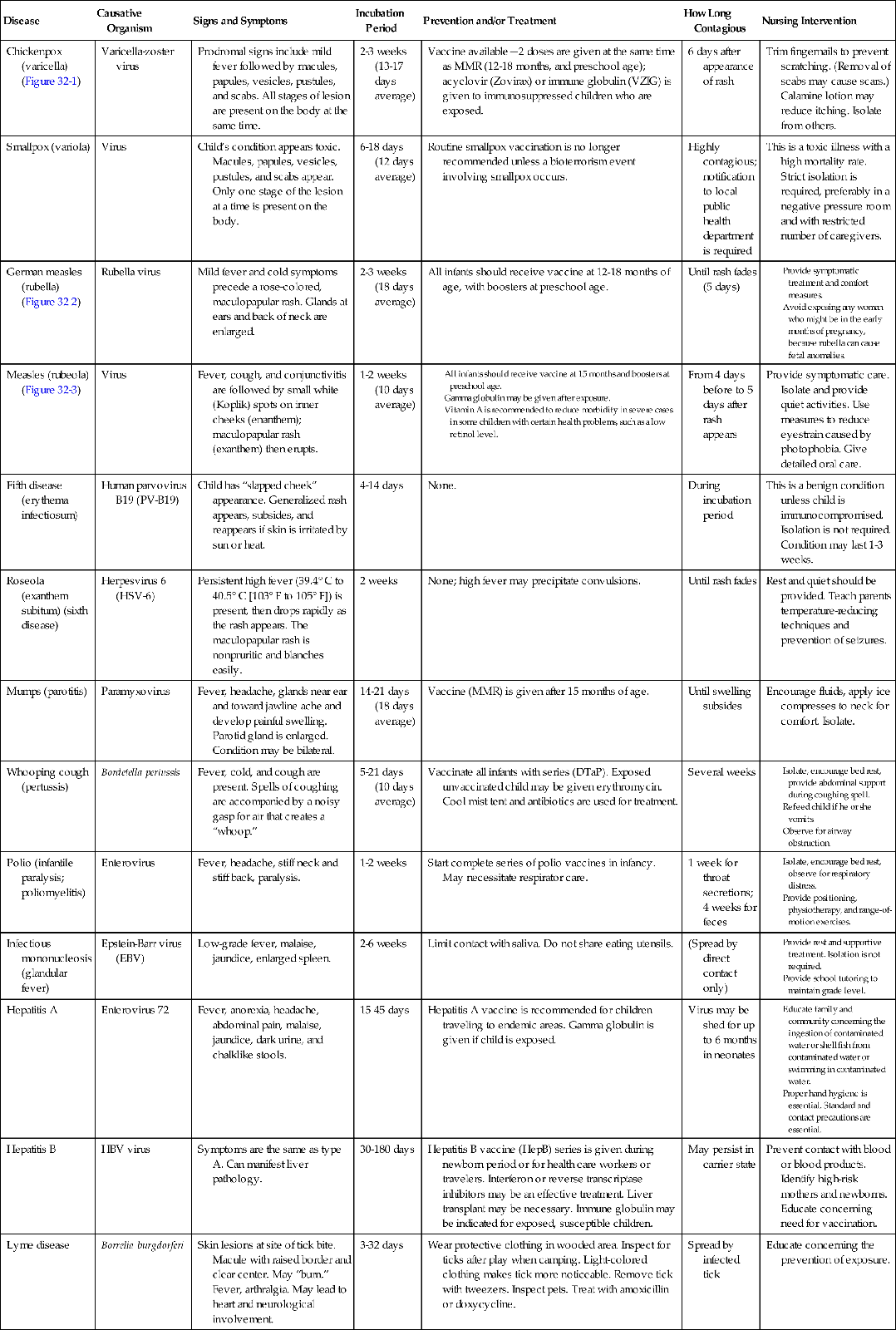

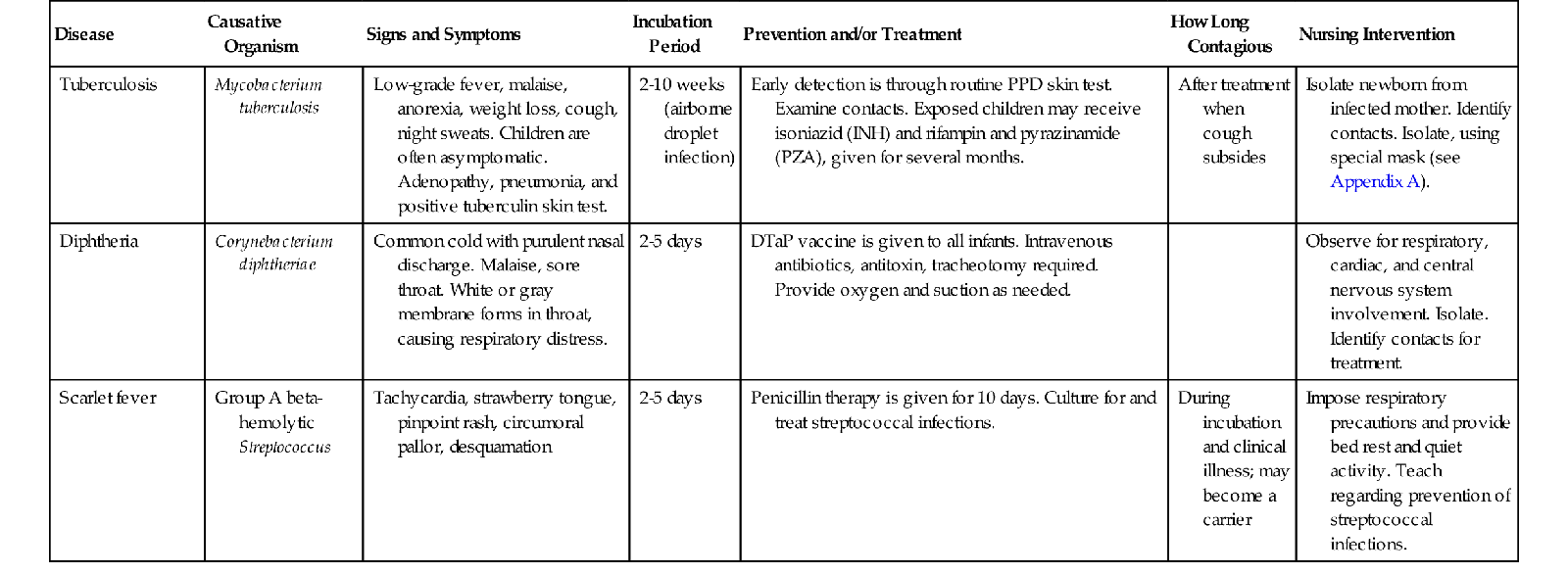

Common Childhood Communicable Diseases

The incidence of common childhood communicable diseases has dramatically decreased as immunological agents have been developed. Diseases such as smallpox have declined to a point worldwide that routine immunizations are no longer recommended. (A brief review of smallpox is presented in this chapter because the nurse must be able to identify a smallpox lesion and promptly isolate the patient and arrange for immediate follow-up care to prevent an outbreak of this deadly illness.) Providing all children with the appropriate immunizations is the health care challenge of today. Air travel is commonplace, and rapid transmission of contagious diseases from around the world makes alert assessment by the nurse and all health care workers essential.

Review of Terms

A communicable disease is one that can be transmitted, directly or indirectly, from one person to another. Organisms that cause disease are called pathogens.

The incubation period is the time between the invasion by the pathogen and the onset of clinical symptoms. The prodromal period refers to the initial stage of a disease: the interval between the earliest symptoms and the appearance of a typical rash or fever. Children are often contagious during this time, but because the symptoms are not specific they may attend preschool or another group program and spread the disease. A fomite is any inanimate material that absorbs and transmits infection. A vector is an insect or animal that carries and spreads a disease. A pandemic is a worldwide high incidence of a communicable disease. An epidemic is a sudden increase of a communicable disease in a localized area. Endemic refers to a continuous incidence of a communicable disease expected in a localized area.

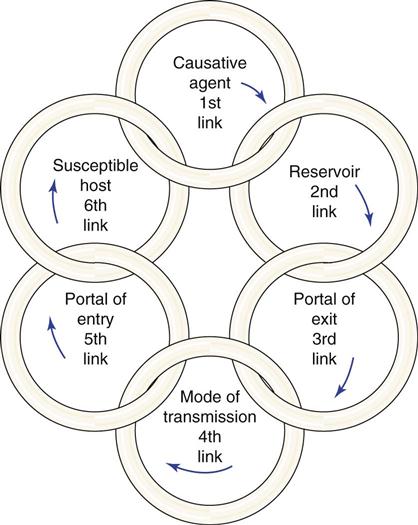

Body substance refers to moist secretions or parts of the body that can contain microorganisms. Emesis, saliva, sputum, semen, urine, feces, and blood are examples of body substances. Body substance precautions indicate the need to wear disposable protective gloves and/or garments when coming in contact with these body substances. A portal of entry is a route by which the organisms enter the body (e.g., a cut in the skin). A portal of exit is the route by which the organisms exit the body (e.g., feces or urine). A reservoir for infection is a place that supports the growth of organisms (e.g., standing, stagnant water). The chain of infection refers to the way in which organisms spread and infect the individual (Figure 32-4). Standard precautions are found in Appendix A. Careful hand hygiene is basic and essential to prevent the spread of infection.

Host Resistance

Many factors contribute to the virulence of an infectious disease. The age, sex, and genetic makeup of the child have a bearing on the degree of resistance. The nutritional status of the person, as well as physical and emotional health, is also important. The efficiency of the blood-forming organs and of the immune systems affects resistance. Important factors in host resistance to disease include the following:

The child who has an underlying condition such as diabetes, cystic fibrosis, burns, or sickle cell disease may be more susceptible to certain organisms. Children with HIV or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or cancer and children receiving steroid or immunosuppressive drugs often have depressed immune systems. This makes them very susceptible to opportunistic infections (an opportunistic infection is caused by organisms normally found in the environment that the immune-suppressed individual cannot resist or fight). An infection acquired in a health care facility during hospitalization is termed a health care–associated infection.

Types of Immunity

Immunity is natural or acquired resistance to infection. In natural immunity, resistance is inborn. Some races apparently have a greater natural immunity to certain diseases than others. Immunity also varies from person to person. If two persons are exposed to the same disease, one may become very ill and the other may show no evidence of the disease.

Acquired immunity is not the result of inherited factors but is gained as a result of having the disease or is artificially acquired by receiving vaccines or immune serums. Vaccines contain live attenuated (weakened) or dead organisms that are not strong enough to cause the disease but stimulate the body to develop an immune reaction and antibodies. When the person produces his or her own immunity, it is called active immunity.

If a person is exposed and needs immediate protection from a specific infectious disease, antibodies can be obtained in immune serums; most are from animals, but some are from humans. For example, tetanus serum (used to prevent lockjaw) is procured from the horse, but gamma globulin, which is rich in antibodies, is obtained from human blood. This type of immunity, known as passive immunity, acts immediately but does not last as long as immunity actively produced by the body. Passive immunity provides the antibody. It does not stimulate the system to produce its own antibodies.

A carrier is a person who is capable of spreading a disease but does not show evidence of it. Typhoid fever is an example of a disease spread by a carrier.

Transmission of Infection

Infection can be transmitted from one person to another by direct or indirect means. Direct transmission involves contact with the person who is infected (the body fluids of that person, such as nasal discharge or an open lesion). Indirect transmission involves contact with objects that have been contaminated by the infected person. These objects are called fomites. Bedrails, intravenous (IV) pumps, overbed tables, door handles, used tissues, countertops, and toys are examples of fomites. For example, the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) lives on dry soap for several hours. Therefore picking up soap used by a person infected with RSV transmits the organism. This is one of the reasons why use of liquid soap is advocated. The chain of infection transmission is shown in Figure 32-4. Preventing the spread of infection depends on breaking the chain.

Various tests are available to determine whether an individual has been exposed to a particular disease, such as the Mantoux intradermal purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test or a blood serum test called the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test, for tuberculosis. The Schick test for diphtheria and the Dick test for scarlet fever have been replaced by serum DNA-PCR (DNA polymerase chain reaction) testing.

Medical Asepsis, Standard Precautions, and Transmission-Based Precautions

The purpose of medical aseptic techniques used with all patients is to prevent the spread of infection from one person to another. A person or object is considered contaminated if he, she, or it has touched the infected patient or any equipment or fomite that has come in contact with the patient or his or her bodily fluids.

Articles that have come in direct contact with the patient must be disinfected before they can be used by others. When something is disinfected, the microorganisms in or on it are killed by physical or chemical means. The autoclave, which uses steam under pressure, is considered effective in killing most microbes when the article is adequately exposed and sterilized for the proper length of time.

All children suspected of having a communicable disease who are admitted to the hospital are placed on both standard and transmission-based precautions until a definite diagnosis is established. A private room or negative-pressure room (prevents air from flowing out of the room when the door is opened) may be assigned. (See Appendix A for specific transmission-based precautions and the practices required.)

Disposable items are used when a child is placed on transmission-based precautions; these include tissues, suction catheters, thermometers, suture sets, nursing bottles, and blood pressure cuffs. They are disposed of according to hospital protocol.

The nurse must understand the importance of protecting himself or herself and others from a contagious patient. This is accomplished by specific precautions, called standard precautions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend standard precautions be used on all patients; these involve, at minimum, hand hygiene and the use of disposable gloves. In addition to these precautions, transmission-based precautions are designed according to the method of spread of infection, such as airborne infection isolation (AII), contact, and droplet (see Appendix A).

Airborne infection isolation precautions are used for patients with conditions such as tuberculosis, varicella (chickenpox), and rubeola (measles). Small airborne particles floating in the air can be inhaled any place in the room. The use of negative-pressure rooms and respirator masks (e.g., N95 particulate masks) are required upon entering the room. The respirator masks are removed upon exiting the room.

Contact precautions are used when the condition causes organisms to be transmitted via skin-to-skin contact or through indirect touch of a contaminated fomite. Gloves and a cover gown are worn for close contact with patients with RSV, patients with hepatitis A who are incontinent, patients with contagious skin diseases such as impetigo, and patients with wound infections. It is important to note that some diseases may have more than one mode of spread and therefore necessitate more than one precaution technique.

Droplet precautions are used with diseases such as pertussis and influenza. When the patient coughs or sneezes, the droplets can contaminate an area 3 feet around the patient. Beyond the 3-foot radius, a mask and gown are not usually necessary.

Standard precautions are discussed in Appendix A along with the protocols for the use of masks, gowns, gloves, and other protective equipment. Personal protective equipment (PPE) should be worn when anticipating the risk of exposure to blood, body fluids, or other potentially infectious materials.

Protective Environment Isolation

Protective environment isolation precautions (previously called reverse isolation) are used for patients who are not communicable but have a lowered resistance and are highly susceptible to infection. This simple procedure reduces the incidence of health care–associated infections. The patient is placed in a private room with the door closed. It is recommended that all persons wear a gown, a mask, and gloves when attending the child. Both the child and family need adequate explanations concerning the protective environment precautions.

Hand Hygiene

The nurse must perform hand hygiene on his or her hands between patients and after removing gloves. Hospital-approved antibacterial soaps and lotions are used. The use of hot water, instead of warm water, can irritate skin and may promote the development of resistant strains of microorganisms. Self-contained liquid soap dispensers are preferable to bar soap, which can harbor organisms. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers can be used as long as the hands are not visibly soiled. Artificial fingernails, including tips, wraps, and nail jewelry are not permitted in patient care areas. Refer to hospital infection prevention and control policies. Caregivers with skin lesions on exposed areas of their bodies should not provide direct patient care until the lesions are completely cleared.

Family Education

Education of family members must be ongoing. Factors to be emphasized include the necessity for immunization of children, proper storage of food (particularly perishables), use of pasteurized milk, proper cooking of meats, cleanliness in food preparation, and proper hand hygiene. The nurse must review the ways in which infectious diseases are spread. Children must be taught to avoid using community hand towels. Other modes of transmission, such as crowded living conditions, insects, rodents, and sandboxes, may also be discussed.

Rashes

Many infectious diseases begin with a rash. Rashes tend to be itchy (pruritic) and uncomfortable. Symptomatic care is provided by prescribing acetaminophen (Tylenol) and diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or topical lotions. Rashes can be described as follows (see Box 30-1):

• Erythema: Diffused reddened area on the skin

• Macule: Circular reddened area on the skin

• Papule: Circular reddened area on the skin that is elevated

• Vesicle: Circular reddened area on the skin that is elevated and contains fluid

• Pustule: Circular reddened area on the skin that is elevated and contains pus

• Scab: Dried pustule that is covered with a crust

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree