The Child with a Skin Condition

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Recall the differences between the skin of the infant and that of the adult.

3. Identify common congenital skin lesions and infections.

4. Describe two topical agents used to treat acne.

6. Discuss the nursing care of various microbial infections of the skin.

7. Discuss the prevention and care of pediculosis and scabies.

9. List five objectives of the nurse caring for the burned child.

10. Describe how the response of the child with burns differs from that of the adult.

11. Identify the principles of topical therapy.

12. Differentiate four types of topical medication.

13. Examine the emergency treatment of three types of burns.

14. Discuss the prevention and treatment of sunburn and frostbite.

Key Terms

allergens (ĂL-ŭr-jĕnz, p. 695)

alopecia (ăl-ō-PĒ-shă, p. 699)

autograft (ĂW-tō-grăft, p. 704)

chilblain (CHĬL-blān, p. 707)

comedo (KŌM-ĕ-dō, p. 694)

crust (p. 691)

Curling’s ulcer (KŬR-lĭngz ŬL-sŭr, p. 704)

debridement (dĕ-BRĒD-măw, p. 704)

dermabrasion (dŭrm-ă-BRĀ-zhŭn, p. 694)

ecchymosis (ĕk-ĭ-MŌ-sĭs, p. 691)

emollient (ĕ-MŎL-ē-ŭnt, p. 696)

eschar (ĔS-kăhr, p. 703)

exanthem (ĕg-ZĂN-thŭm, p. 690)

frostbite (p. 707)

heterograft (HĔT-ŭr-ō-grăft, p. 704)

hives (p. 690)

homografts (HŌ-mō-grăfts, p. 704)

ileus (ĬL-ē-ŭs, p. 704)

isograft (Ī-sō-grăft, p. 704)

macule (MĂK-yūl, p. 691)

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (mĕth-ĭ-SĬL-ĭn rē-zĭs-tĕnt stăf-ĭ-lō-KŎK-ŭs ĂW-rē-ŭs, p. 698)

papule (PĂP-yūl, p. 691)

pediculosis (pĕ-dĭk-yū-LŌ-sĭs, p. 700)

pruritus (prū-RĪ-tŭs, p. 692)

pustule (PŬS-tyūl, p. 691)

sebum (p. 694)

stye (p. 691)

total body surface area (TBSA) (p. 701)

vesicle (VĔS-ĭ-kŭl, p. 691)

wheal (WĒL, p. 691)

xenografts (ZĒ-nō-grăfts, p. 704)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

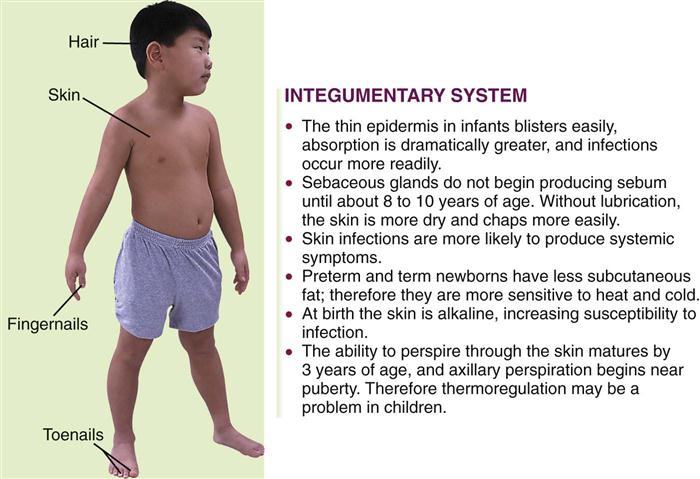

Skin Development and Functions

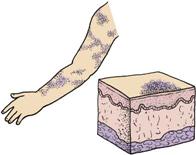

The main function of the skin is protection. It acts as the body’s first line of defense against disease. It prevents the passage of harmful physical and chemical agents and prevents the loss of water and electrolytes. It also has a great capacity to regenerate and repair itself. The skin and the structures derived from it, such as hair and fingernails, are known as the integumentary system. Figure 30-1 depicts these structures and how they differ in the developing child and in the adult.

Maintaining skin integrity is important to self-esteem and therefore has both a psychological and a physiological component. This is particularly evident in patients with facial disfiguration. Four basic skin sensations—pain, temperature, touch, and pressure—are felt by the skin in conjunction with the nervous system. The skin also secretes sebum, which helps to protect and maintain its texture. The outer surface of the skin is acidic, with a pH of 4.5 to 6.5 to protect the skin from pathological bacteria, which thrive in an alkaline environment.

The skin is composed of two layers: the epidermis (derived from the ectoderm) and the dermis (derived from the mesoderm). Vernix caseosa, a cheeselike substance, covers the fetus until birth. This protects the fetal skin from maceration as the fetus floats in its watery home. The fetal skin is at first so transparent that blood vessels are clearly visible. Downy lanugo hair begins to develop at about 13 to 16 weeks, especially on the head. At 21 to 24 weeks the skin is reddish and wrinkled, with little subcutaneous fat. Adipose tissue forms during later weeks. At birth the subcutaneous glands are well developed, and the skin is pink and smooth and has a polished look. It is thinner than the skin of an adult.

Skin Disorders and Variations

Certain skin conditions in children may be associated with age, as in the case of milia in infants and acne in adolescents. A skin condition may be a manifestation of a systemic disease, such as chickenpox. Some lesions, such as strawberry nevi and mongolian spots, are congenital. Other skin lesions, such as those seen in rubella and fifth disease, are self-limited and do not necessitate treatment.

There are great individual differences in skin texture, color, pH, and moisture. Skin color is an important diagnostic criterion in cases of liver disease, heart conditions, and child abuse and for overall assessment. Complete blood counts and serum electrolyte levels are helpful in diagnosing skin conditions. Skin tests are used in diagnosing allergies. The purified protein derivative (PPD) test is useful in screening for tuberculosis. Skin scrapings are used for microscopic examination. The Wood’s light is an instrument used to diagnose certain skin conditions. It reflects a particular color according to the organism present.

Hair condition is important to observe. Hair is inspected for color, texture, quality, distribution, and elasticity. Hair may become dry and brittle and may lack luster owing to inadequate nutrition. Hair may begin to fall out or even change color during illness or the ingestion of certain medications.

Skin conditions may be acute or chronic. The nurse should describe the lesions with regard to size, color, configuration (e.g., butterfly rash), presence of pain or itching, distribution (e.g., arms, legs, behind ears), and whether the rash is general or local. Hives, a general rash that appears abruptly, is often an allergic or medication reaction. The condition of the skin around the lesions is also significant, as is the skin turgor. Managing itching is a key component in preventing secondary infection from scratching. Dressings and ointments are applied as prescribed. Preventing infections is a consideration in open wounds. Mongolian spots and physiological jaundice are covered in Chapters 12 and 14. The communicable diseases are discussed in Chapter 32.

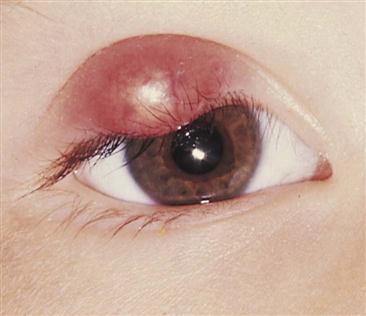

Many childhood infectious diseases, such as measles, German measles, and chickenpox, involve the presence of an exanthem (a skin rash). Box 30-1 identifies terms used to describe some conditions of the skin that the nurse may witness. Some rashes begin as one lesion and evolve into others. For example, the sequence of chickenpox rash is macule to papule, to vesicle, and then to crust. A stye is an infection of the sebaceous gland of the eyelash (Figure 30-2).

Congenital Lesions

Strawberry Nevus

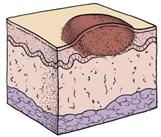

The strawberry nevus (Figure 30-3) is a common hemangioma (consists of dilated capillaries in the dermal space) that may not become apparent for a few weeks after birth. Although it is harmless and usually disappears without treatment, it is disturbing to parents, especially when it appears on the head or face. At first it is flat, but it gradually becomes raised. The lesion is bright red, elevated, and sharply demarcated. The lesions gradually blanch, with 60% disappearing spontaneously by 5 years of age and 90% disappearing by 9 years of age. Laser treatment or excision may be considered if the area becomes ulcerated. Parents are often quizzed about the growth by insensitive persons and may be advised of various unorthodox treatments. The nurse offers support and reassurance to parents and corrects misinformation. After laser surgery, the skin may appear black for 7 to 10 days. Salicylates should be avoided, and sun exposure should be minimized.

Port-Wine Nevus

Port-wine nevi (Figure 30-4) are present at birth and are caused by dilated dermal capillaries. The lesions are flat, sharply demarcated, and purple to pink. The lesion darkens as the child gets older. If the area is small, cosmetics may disguise the lesion. If the area is large, laser surgery may be indicated.

Skin Manifestations of Illness

Infections

Miliaria

Pathophysiology.

Miliaria (prickly heat) refers to a rash caused by excess body heat and moisture (Figure 30-5). There is a retention of sweat in the sweat glands, which have become blocked or inflamed. Rupture or leakage into the skin causes the inflamed response. It appears suddenly as tiny, pinhead-sized, reddened papules with occasional clear vesicles. It may be accompanied by pruritus (itching). It is seen in infants during hot weather or in newborns that sleep in overheated rooms. It often occurs in the diaper area or in the folds of the skin where moisture accumulates. Plastic enclosures on diapers hold in body warmth that results in a rash. This harmless condition may be reversed by removing extra clothing, bathing, skin care, and frequent diaper changes.

Intertrigo

Pathophysiology.

Intertrigo (in, “into,” and terere, “to rub”) is the medical term for chafing. It is a dermatitis that occurs in the folds of the skin (Figure 30-6). The patches are red and moist and are usually located along the neck and in the inguinal and gluteal folds. This condition is aggravated by urine, feces, heat, and moisture. Obese children are more prone to intertrigo. Prevention consists of keeping the affected areas clean and dry. The child is allowed to be out of diapers to expose the area to air and light. Maceration of the skin can lead to secondary infections.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Pathophysiology.

Seborrheic dermatitis (cradle cap) is an inflammation of the skin that involves the sebaceous glands (Figure 30-7). It is characterized by thick, yellow, oily, adherent, crustlike scales on the scalp and the forehead. The skin beneath the patches may be red (erythematous). Less often it may involve the eyelids, the external ear, and the inguinal area. Secondary bacterial and yeast infections may occur. It is seen in newborns, in infants, and at puberty. In newborns it is commonly known as “cradle cap.” It is seen in infants with sensitive skin, even when the head and hair are washed frequently. Seborrhea resembles eczema, but it usually does not itch and there is a negative family history. In adolescence it is more localized and is usually confined to the scalp. A condition resembling seborrheic dermatitis is common in children and adolescents infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Treatment.

Treatment consists of shampooing the hair on a regular basis. Scales that are particularly stubborn in newborns may be softened by applying baby oil to the head the evening before and shampooing in the morning. The scalp is rinsed well. A soft brush is helpful in removing loose particles from the hair. The nurse teaches the parent how to shampoo an infant’s head using the football hold (see Figure 22-4). A dandruff-control shampoo is used for adolescents. Medications such as sulfur, salicylic acid, or hydrocortisone may be prescribed. Topical antifungal agents effective against Pityrosporum have also been suggested. The response to therapy is usually rapid.

Diaper Dermatitis

Pathophysiology.

Diaper dermatitis (diaper rash) is a commonly seen condition that results from prolonged contact of the skin to a mixture of urine and feces. The urine increases the pH of the skin, resulting in increased sensitivity to fecal enzymes. If the skin remains moist inside the soiled diaper, the skin may become more likely to develop a Candida albicans infection. The rash of simple diaper dermatitis may appear as an erythema (redness); however, a beefy red rash in the diaper area may be indicative of a Candida (thrush) infection and necessitates prompt treatment (Figure 30-8). Disposable diapers contain a super-absorbent gel material that helps maintain normal skin pH and therefore reduces the occurrence of diaper dermatitis.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

It is easier to prevent diaper rash than to cure it. This is accomplished by frequent diaper changes to limit the skin’s exposure to moisture. The diaper is periodically removed to expose the skin to light and air. With each diaper change, the perineal area is gently and thoroughly cleansed (preferably with warm water) and gently dried. After bowel movements, the area is cleansed with mild soap and water. The skin folds are thoroughly washed, rinsed, and dried. A cloth, non–alcohol-containing wipe or a cosmetic pad may be used to remove feces from the skin. Some common over-the-counter ointments for prevention of diaper dermatitis include ointments with the active ingredients of vitamins A and D and lanolin, and other products containing 10% zinc oxide. Products with a higher percentage of zinc oxide are protective but hard to wash off. Aggressive scrubbing of the skin should be avoided. Mineral oil can aid in removing sticky ointments. The use of corticosteroid ointments in an occluded diaper area should be avoided since skin absorption can cause systemic complications (Eichenfeld et al., 2008).

Acne Vulgaris

Pathophysiology.

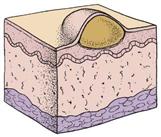

Acne is an inflammation of the sebaceous glands and hair follicles in the skin (Figure 30-9). Because of hormonal influence, the sebaceous glands enlarge at puberty and secrete increased amounts of a fatty substance called sebum. Genetic factors and stress are also thought to play a part. The course of acne may be brief or prolonged (lasting 10 years or longer). Premenstrual acne in girls is not uncommon. The principal lesions include comedones, papules, and nodulocystic growths.

A comedo (plural, comedones) is a plug of keratin, sebum, or bacteria. Keratin is a protein substance and is the main constituent of epidermis and hair. There are two types of comedones: open and closed. In the open comedo, or blackhead, the surface is darkened by melanin. Closed comedones, or whiteheads, are responsible for the inflammatory process of acne. With continued buildup, the walls of the follicle rupture, releasing their irritating contents into the surrounding skin. A pustule may appear when this develops near the exterior. This process occurs no matter how carefully the teenager washes because surface bacteria are not involved in the pathogenesis. Acne is usually seen on the chin, the cheeks, and the forehead. It can also develop on the chest, the upper back, and the shoulders. It usually is more severe in winter.

Treatment.

The basic treatment of acne has changed considerably over the past few years. It is no longer thought that certain foods trigger the condition; therefore the restriction of chocolate, peanuts, and cola drinks is unwarranted. A regular, well-balanced diet is encouraged. Patients who are not taking tetracycline or vitamin A benefit from sunshine. General hygienic measures of cleanliness, rest, and the avoidance of emotional stress may help to prevent exacerbations.

Routine skin cleansing is indicated, and greasy hair and cosmetic preparations should be avoided. Excessive cleansing of the skin can irritate and chap the tissues. Squeezing pimples ruptures intact lesions and causes local inflammation. The topical preparations recommended include benzoyl peroxide gels or lotions that dry and peel the skin and suppress fatty acid growth. Tretinoin acid (Retin-A) helps eliminate keratinous plugs. Vitamin A can increase sensitivity to the sun, so precautions should be taken when it is used. Tetracycline, erythromycin, doxycycline (Vibramycin), or minocycline (Minocin) may be given in conjunction with topical medications in more serious cases. Monilial vaginitis is a secondary complication sometimes seen when these drugs are used, and this should be explained to the unsuspecting adolescent girl.

Isotretinoin (Accutane) is given to patients with severe pustulocystic acne who have been unable to benefit from other types of treatment. It has many side effects; thus the patient must be carefully monitored with liver studies and lipid levels. It is not prescribed during pregnancy or to those at risk for pregnancy because of the possibilities of fetal deformity. Planing of the skin to minimize scarring (dermabrasion) is done selectively, because it is not always successful. Oral contraceptives (OCs) such as Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate and ethinyl estradiol) may also be given because sebum production is controlled by androgens, and these OCs reduce androgen levels.

Acne is distressing to the adolescent, particularly when the face is extensively involved. Sometimes even a minimal problem is seen as disastrous when it happens before an important event. The self-conscious young person feels different and embarrassed. The nurse who is attuned to the feelings of individuals can provide understanding support. Although the adolescent is educated to assume responsibility for the regimen, including the parents helps to prevent conflict surrounding it. Drug-induced acne can occur in children taking long-term steroids, phenobarbital, phenytoin, lithium, vitamin B12, or medications containing iodides or bromides.

Herpes Simplex Type I

Pathophysiology.

Herpes simplex type I, a viral infection, is commonly known as a cold sore or fever blister. It may begin with a feeling of tingling, itching, or burning on the lip. Vesicles and crusts form (Figure 30-10). Spontaneous healing occurs in about 8 to 10 days. Communicability is highest early in the formation and is spread by direct contact. Recurrence is common because the virus lies dormant in the body until it is activated by stress, sun exposure, menstruation, fever, and other causes. Patients must become familiar with their own personal triggers. Herpes can be serious in newborns and in the patients who are immunocompromised.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Topical acyclovir may reduce viral shedding and hasten healing. In the hospital, ointments are applied with gloved hands. Contact and protective environment precautions should be followed (see Appendix A). Patients are instructed not to pick at lesions, because this may produce spreading to other sites. They should not share lipstick and should avoid kissing while lesions are active. Sensitivity to the self-conscious adolescent who has a cold sore is important. Genital herpes caused by the herpes virus type II and spread by sexual contact is discussed in Chapter 11 and Table 11-1. The distinction between the two types has become less clear because of an increase in the practice of oral-genital sex.

Infantile Eczema

Pathophysiology.

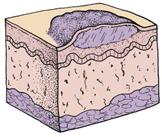

Infantile eczema, or atopic dermatitis, is an inflammation of genetically hypersensitive skin (Figure 30-11). The pathophysiology is characterized by local vasodilation in affected areas. This progresses to spongiosis, or the breakdown of dermal cells and the formation of intradermal vesicles. Chronic scratching produces weeping and results in lichenification, or coarsening, of the skin folds. The exact cause of this condition is difficult to pinpoint because it is thought to be caused mainly by allergy. Infantile eczema is rarely seen in breastfed infants until they begin to eat additional food. It seems to follow a definite familial history of allergies; emotional factors are often involved.

Eczema is actually a symptom rather than a disorder. It indicates that the infant is oversensitive to certain substances called allergens, which enter the body via the digestive tract (food), by inhalation (dust, pollen), by direct contact (wool, soap, strong sunlight), or by injections (insect bites, vaccines). Some children develop the triad of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and hay fever.

Manifestations.

Although infantile eczema can occur at any age, it is more common during the first 2 years. The pruritic lesions form vesicles that weep and develop a dry crust. They are more severe on the face but may occur on the entire body, particularly in the skin folds. Eczema is worse in the winter than in the summer and has periods of temporary remission.

The infant scratches because the itching is constant, and he or she is irritable and unable to sleep. The lesions become easily infected by bacterial or viral agents. Infants and children with eczema should not be exposed to adults with cold sores because they may develop a systemic reaction with high fever and multiple vesicles on the eczematous skin. Eczema may flare up after immunization. Laboratory studies may show an increase in immunoglobulin E (IgE) and eosinophil levels.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Treatment of the child with infantile eczema is aimed at relieving pruritus (itching), hydrating the skin, relieving inflammation, and preventing infection. An emollient bath is sometimes ordered for its soothing effect on the skin. Oatmeal and a mixture of cornstarch and baking soda are examples of emollients prescribed. The infant’s hair is washed with a soap substitute rather than a shampoo. Some dermatologists think that bathing should be kept to a minimum. The physician may suggest that a bath oil such as Alpha Keri Therapeutic Bath Oil be used as the lesions begin to heal. This prevents the skin from becoming too dry. To be correctly used, bath oils should be added after the patient has soaked for a while and the skin is hydrated. In this way, moisture is sealed rather than excluded, as it is when oil is added before the patient gets into the tub.

Whenever possible, patients are treated at home because of the danger of infection in the hospital. When soap is used, a mild, nonperfumed soap such as Dove or Neutrogena is used. Glycerin-based lubricants are preferred over lanolin, which may be an irritant to an infant who is allergic to wool (Perry et al., 2010). Aquaphor and Eucerin are lotions that can be used to enhance skin hydration.

Corticosteroids may be administered systemically or locally. Antibiotics are needed if infection is present. Medication to help relieve itching is ordered for the patient. A child who is uncomfortable and unable to sleep may receive sedation.

The nurse plays a vital role in the treatment of patients with skin problems (Nursing Care Plan 30-1). The nurse should assess the family’s ability to cope with the care of this child at home. Techniques of home bathing or application of soaks combined with quiet playtime enhances family coping. Control of itching is essential. Ointments are applied with a gloved hand to minimize contact with the skin. The fingernails of the child are kept short, and cotton gloves or socks can be used to prevent scratching. Appropriate dress is advised, as is using cotton fabric and avoiding wool and stuffed animals because of their allergy potential. Clothes should be laundered using mild soaps, avoiding products that contain fragrances or harsh chemicals. Parents should be taught the principles of general hygiene to prevent secondary infection of the open skin lesions. A hypoallergenic formula and a plan to identify possible food allergens are explained to parents. When a food allergen is the cause of eczema, stopping the food results in a clearing of the skin; however, restarting the food after a time may cause an anaphylactic reaction. The types of topical medications are listed in Table 30-1.