Case 3 | Parkinson’s Disease

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 8% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

This man has an expressionless, unblinking face and slurred low-volume monotonous speech. He is drooling (due to excessive salivation and some dysphagia) and there is titubation. He has difficulty starting to walk (‘freezing’) but once started, progresses with quick shuffling steps as if trying to keep up with his own centre of gravity. As he walks, he is stooped and he does not swing his arms which show a continuous pill-rolling tremor. (He has poor balance and tends to fall, being unable to react quickly enough to stop himself.) His arms show a lead-pipe rigidity at the elbow but cog-wheel rigidity (combination of lead pipe rigidity and tremor, i.e. worse with anxiety) at the wrist. He has a positive glabellar tap sign (an unreliable sign) and his signs generally are asymmetrical – note the greater tremor in the R/L arm. (The tremor is decreased by intention but handwriting may be small,* tremulous and untidy.) There is blepharoclonus (tremor of the eyelids when the eyes are gently closed).

The diagnosis is Parkinson’s disease.†

Male-to-female ratio is 3/1.

The Features of Parkinson’s Disease are

Bradykinesia (the most disabling) can be demonstrated by asking the patient to touch his thumb successively with each finger. He will be slow in the initiation of the response and there will be a progressive reduction in the amplitude of each movement and a peculiar type of fatiguability. He will also have difficulty in performing two different motor acts simultaneously.

Other Causes of the Parkinsonian Syndrome

Other Conditions Which May have Some Extrapyramidal Features

NB: A condition which is often misdiagnosed as Parkinson’s disease in the elderly is benign essential tremor (often autosomal dominant, intention tremor worse with stress, no other neurological abnormality; usually improves when alcohol is taken and sometimes with diazepam or propranolol).

Stiff-Person Syndrome (SPS)

This is a rare disease of severe progressive muscle stiffness of the spine and lower extremities with superimposed muscle spasms triggered by external stimuli or emotional stress. When stiffness and spasms are present together, patients have difficulty ambulating and are prone to unprotected falls, i.e. falls like a tin soldier. When in spasm the muscles are hard to palpation. Typically symptoms begin between the age of 30 and 50 and respond to benzodiazepines. EMG shows a characteristic abnormality and anti-GAD (glutamic acid decarboxylase) antibodies* are present in 60%. In GAD antibody-positive SPS there is a strong association with other autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, pernicious anaemia and vitiligo (see Vol. 3, Station 5, Skin, Case 8).

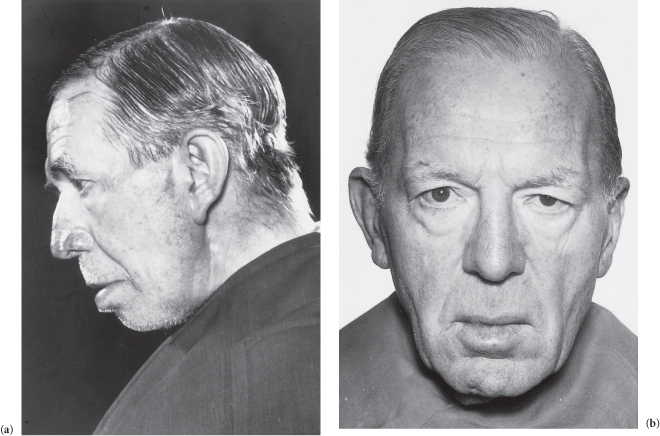

Figure C3.5 (a,b) Parkinson’s disease.

Case 4 | Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease (Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy)*

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 6% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

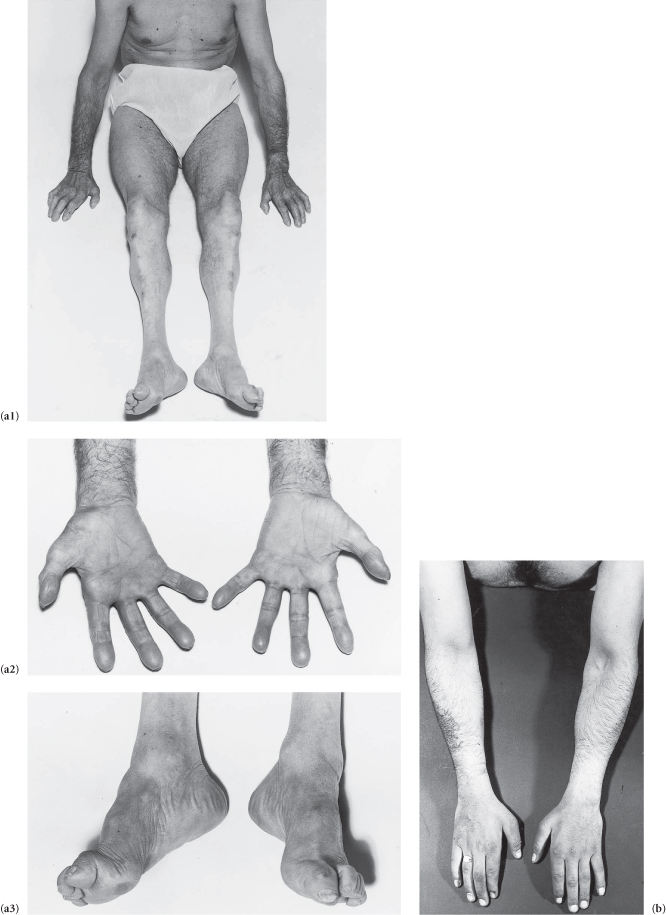

There is distal wasting of the lower limb muscles with relatively well-preserved thigh muscles.† The feet show pes cavus and clawing of the toes, and there is weakness of the extensors of the toes and feet. The ankle jerks are absent and the plantar reflexes show no response. There is only slight distal involvement of superficial modalities of sensation (though occasionally marked sensory loss may lead to digital trophic ulceration). The lateral popliteal (?and ulnar) nerves are palpable (in some families only). The patient has a steppage gait (bilateral foot-drop). There is (may be) wasting of the small muscles of the hand.

The diagnosis is Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease.*

Patterns of inheritance are variable.

The degree of disability in this condition is commonly surprisingly slight in spite of the remarkable deformities. Toe retraction and talipes equinovarus may occur and fasciculation (much less apparent than in motor neurone disease) is sometimes seen.

The degeneration is mainly in the motor nerves. It is sometimes also found in the dorsal roots and dorsal columns, and slight pyramidal tract degeneration is often seen (however, in classic cases extensor plantars are not found). The condition usually becomes arrested in mid-life. Other members of the patient’s family may have a forme fruste and show just minor signs such as pes cavus and absent ankle jerks only.

Figure C3.6 (a1–3) Note that the muscle wasting stops in the thighs, foot-drop, pes cavus, and wasting of the small muscles of the hand all in the same patient. (b) Distal wasting in the upper limbs.

Case 5 | Abnormal Gait

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 6% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Survey Note:

relative frequencies in the survey were cerebellar ataxia 45%, spastic paraplegia 27%, sensory ataxia 9%, Parkinson’s disease 9% and Charcot–Marie–Tooth (steppage gait) 9%. Hemiplegia, waddling gait and gait apraxia did not occur in our survey.

Record 1

The gait is wide-based and the arms are held wide (both upper and lower limbs tend to tremble and shake). The patient is ataxic and tends to fall to the R/L, especially during the heel-to-toe test which he is unable to perform. Romberg’s test is negative.

This suggests cerebellar disease which is predominantly R/L sided. (Now, if allowed, examine for other cerebellar signs: finger–nose, rapid alternate motion, nystagmus, staccato dysarthria, etc; see Station 3, CNS, Case 7.)

Possible Causes

Record 2

The patient has a stiff, awkward ‘scissors’ or ‘wading through mud’ gait.

This suggests spastic paraplegia. (Now, if allowed, examine tone, reflexes, plantars, sensation, etc; see Station 3, CNS, Case 6)

Possible Causes

Record 3

The gait is ataxic and stamping (his feet tend to ‘throw’; both the heels and the toes slap on the ground). The patient walks on a wide base, watching his feet and the ground (to some extent he can compensate for lack of sensory information from the muscles and joints by visual attention). He has difficulty walking heel-to-toe and the ataxia becomes much worse when he closes his eyes; Romberg’s test is positive.

He has sensory ataxia (now look for Argyll Robertson pupils and for clinical anaemia).

Possible Causes

Record 4

This (depressed, expressionless, unblinking and stiff) patient stoops and his gait, initially hesitant, is shuffling and has lost its spring. The arms are held flexed and they do not swing. The hands show a pill-rolling tremor. His gait is festinant, i.e. he appears to be continually about to fall forward as if chasing his own centre of gravity.

He has Parkinson’s disease.* (Now examine the wrists for cog-wheel rigidity, elbows for lead-pipe rigidity, and for the glabellar tap sign, etc; see Station 3, CNS, Case 3).

Record 5

The patient has a steppage gait. He lifts his R/L foot high to avoid scraping the toe because he has a R/L foot-drop. He is unable to walk on his R/L heel (heel walking difficulty is an excellent way of testing subtle dorsiflexion weakness).

Possible Causes

Record 6

The R/L leg is stiff and with each step he tilts the pelvis to the other side, trying to keep the toe off the ground; the R/L leg describes a semi-circle with the toe scraping the floor and the forefoot flopping to the ground before the heel. The R/L arm is flexed and held tightly to his side and his fist is clenched.*

The patient has a hemiplegic gait.

Record 7

The patient has a lumbar lordosis and walks on a wide base with a waddling gait, his trunk moving from side to side and his pelvis dropping on each side as his leg leaves the ground. At each step his toes touch the ground before his heel. (This is a description of the typical gait of a patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the most common cause of a waddling gait. Other conditions causing wasting or weakness of the proximal lower limb (see Station 3, CNS, Case 23) and pelvic girdle muscles also cause it, e.g. polymyositis, rickets/osteomalacia.)

Record 8

The patient (an elderly person) walks with a broad-based gait, taking short steps and placing his feet flat on the ground like a person ‘walking on ice’ – so-called ‘sticky feet’. This is probably why this gait is also referred to as a magnetic gait. Neither turning nor straight walking is fluent. (There is a tendency to retropulsion which increases the danger of falling.) The patient cannot hop on one foot.

This is gait apraxia (a common but little recognized disorder of the elderly; frontal lobe signs including dementia and positive grasp and suck reflexes will confirm the diagnosis). The most common cause is a degenerative process similar to Alzheimer’s disease. Other causes include subdural haematoma, tumour, normal pressure hydrocephalus or a lacunar state.

Case 6 | Spastic Paraparesis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 6% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

The tone in the legs is increased and they are weak (in chronic immobilized cases there may be some disuse atrophy, and in severe cases there may be contractures). There is bilateral ankle clonus, patellar clonus and the plantar responses are extensor. (?Abdominal reflexes; consider testing gait if the patient can walk.*)

The patient has a spastic paraparesis.† The most likely causes are:

Other Causes

Case 7 | Cerebellar Syndrome

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 5% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record 1

There is nystagmus to the R/L and there is ataxia with the eyes open as shown by impairment of rapid alternate motion on the same side (dysdiadochokinesis). The finger–nose test is impaired on the R/L with past pointing to that side and an intention tremor (increases on approaching the target). The heel–shin test is impaired on the R/L and the gait is ataxic with a tendency to fall to the R/L. There is ataxic dysarthria with explosive speech (staccato).

The patient has a R/L cerebellar lesion.

Causes Include

Other Causes of Cerebellar Ataxia Include

Other Cerebellar Signs

Record 2 (Vermis Lesion)

There is a wide-based cerebellar ataxia (ataxic gait and rombergism more or less the same with eyes open and closed; cf. sensory ataxia – worse with eyes closed), but there is little or no abnormality of the limbs when tested separately on the bed. This suggests a lesion of the cerebellar vermis.

Case 8 | Hemiplegia

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 4% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

There is a R/L upper motor neurone weakness of the facial muscles.* The R/L arm and leg are weak (without wasting) with increased tone and hyperreflexia. The R/L plantar is extensor and the abdominal reflexes are diminished on the R/L side.

This is a R/L hemiplegia.

There is also (may be) hemisensory loss on the R/L side. Visual field testing reveals (may be) a R/L homonymous hemianopia. The most likely causes are:

A right-sided hemiplegia associated with dysphasia would suggest (in a right-handed patient) that the causative lesion is affecting the speech centres in the dominant hemisphere (see Station 3, CNS, Case 40) as well as the motor cortex (precentral gyrus) and if there are sensory signs, the sensory cortex (postcentral gyrus). If cerebrovascular in origin, the causative lesion is likely to be in the carotid distribution.

The presence of signs such as nystagmus, ocular palsy, dysphagia (?nasogastric or PEG feeding tube) and cerebellar signs suggests that the hemiparesis is due to a brainstem lesion. If cerebrovascular in origin, the lesion is likely to be in vertebrobasilar distribution (see Station 3, CNS, Case 44 for the eponymous syndromes†).

Parietal Lobe and Related Signs‡

Apraxia. Whereas in agnosia the difficulty is in recognition, in apraxia it is in execution. Though power, sensation and coordination are all normal, the patient is unable to perform certain familiar activities. It may affect:

The lesions (tumours or atrophy) tend to be in the corpus callosum, parietal lobes and premotor areas. Dominant lobe lesions may produce bilateral apraxia. Unilateral left-sided apraxia may be caused by a lesion in the right posterior parietal region or in the corpus callosum of a right-handed patient. The lesion in ‘dressing apraxia’ is usually in the right parietooccipital region. In ‘constructional apraxia’ (most often seen in patients with hepatic encephalopathy), the patient is unable to construct simple figures such as triangles, squares or crosses from matchsticks.

Dyslexia (impairment of reading ability), dysgraphia (impairment of writing ability) and dyscalculia (difficulty with calculating) usually represent lesions in the posterior parietal lobe.

Proprioceptive loss due to a parietal lesion may not infrequently be seen and may present as an ‘alien hand’ – the patient failing to control the limb when it is not in direct vision.

Case 9 | Muscular Dystrophy

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Survey Note:

most cases in the surveys seem to be facioscapulohumeral except one possible case of limb-girdle type.

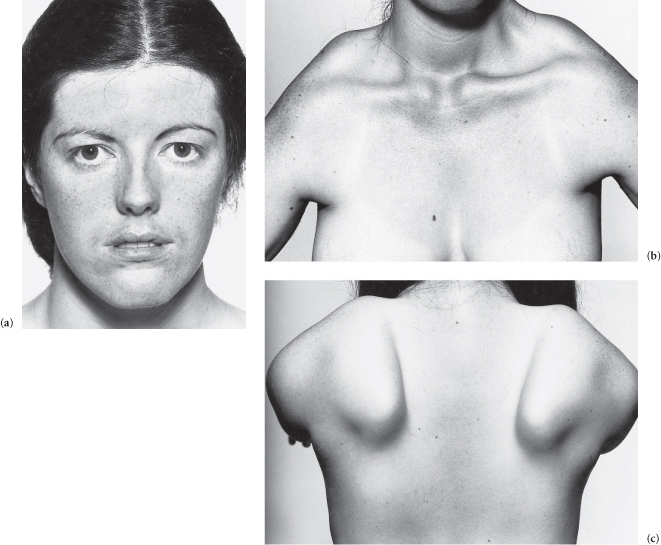

Record 1

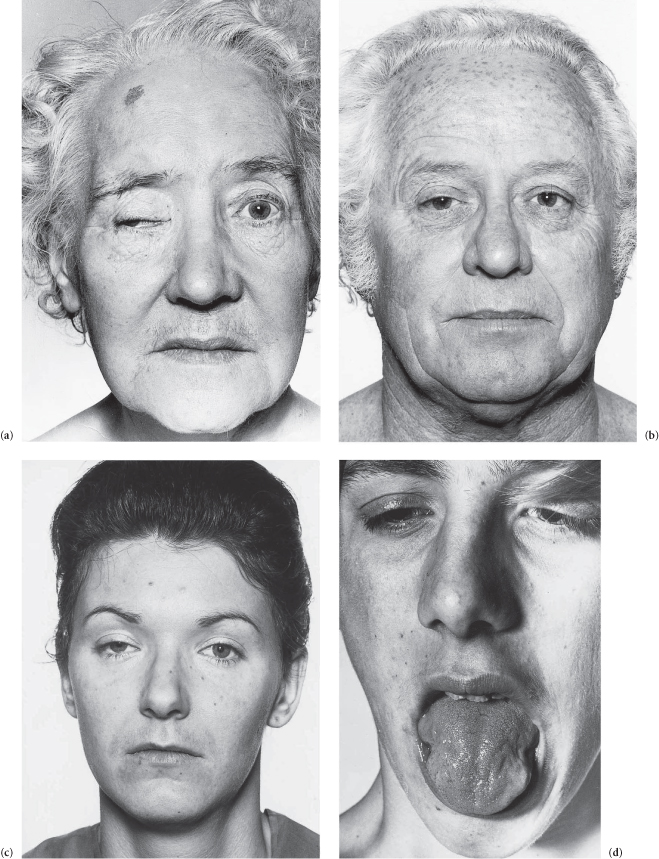

The patient has a dull, unlined, expressionless face (myopathic facies) with lips that are (usually) open and slack. There is wasting of the facial and limb-girdle muscles, and the superior margins of the scapulae (viewed from the front) are (may be) visible above the clavicles. The movements of smiling, whistling and closing the eyes are impaired. There is winging of the scapulae (when the patient leans against a wall with arms extended). There is (may be) involvement of the trunk and legs (anterior tibials may cause bilateral foot-drop) now or in the future.

The diagnosis is facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy* (autosomal dominant, course variable but usually relatively benign).

Record 2

There is limb-girdle wasting and weakness which affects some groups of muscles more than others (e.g. deltoid and spinati are usually spared), and the face is spared. There is (not uncommonly) enlargement of the calf muscles.

These features suggest limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (autosomal recessive, both sexes affected equally, more benign if the upper limb is involved first, usually begins in the second or third decade, sometimes arrests but usually patients are severely disabled within 20 years of onset).

Other Muscular Dystrophies

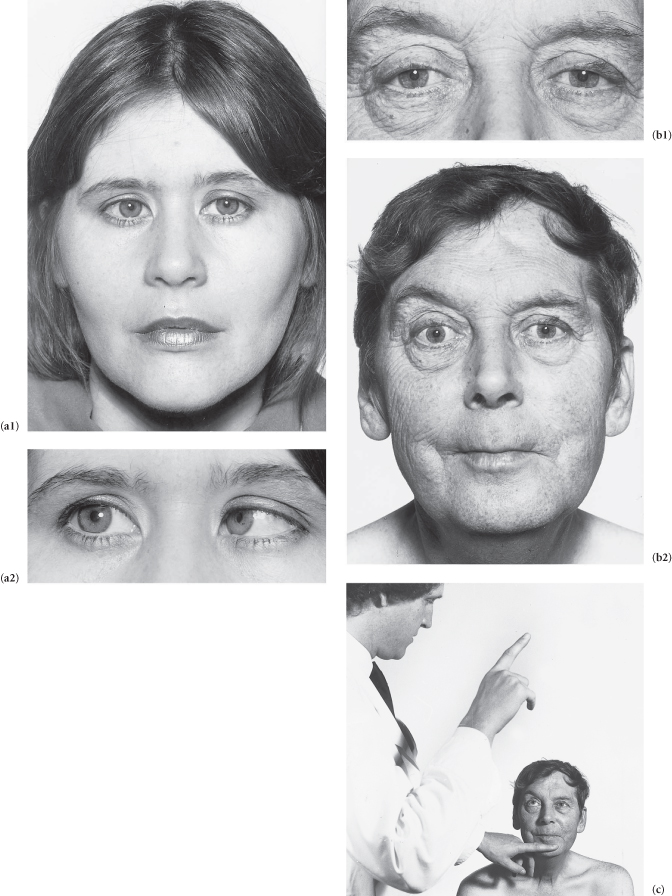

Figure C3.7 (a) Myopathic facies (facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy). (b) The superior margins of the scapulae are visible from the front (same patient as (a)). (c) Winging of the scapulae (same patient).

Case 10 | Multiple Sclerosis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record 1

The patient (?a young adult) has ataxic nystagmus (see Station 3, CNS, Case 32), internuclear ophthalmoplegia (see Station 3, CNS, Case 16), temporal pallor of the discs (see Vol. 3, Station 5, Eyes, Case 3), and slurred speech (see Station 3, CNS, Case 36) with ataxia (see Station 3, CNS, Case 5) and widespread cerebellar signs (see Station 3, CNS, Case 7). There are pyramidal signs and dorsal column signs.

The likely diagnosis is demyelinating disease* (a useful euphemism for multiple sclerosis).

Record 2

The legs of this (?middle-aged) patient have increased tone, they are bilaterally spastic and weak. There is bilateral ankle clonus and patellar clonus and the plantars are extensor. The abdominal reflexes are absent. The heel–shin test suggests some ataxia in the legs and there is slight impairment of rapid alternate motion in the upper limbs.

These features suggest that this spastic paraplegia is due to demyelinating disease. An examination of the fundi may show involvement of the discs.†

Male-to-female ratio is 2/3.

Features of Multiple Sclerosis

MRI scans often detect many more MS lesions than are suspected clinically (CT scans can also detect lesions but are much less sensitive than MRI). Gadolinium enhancement of the MRI lesions suggests active inflammation.

Case 11 | Motor Neurone Disease

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

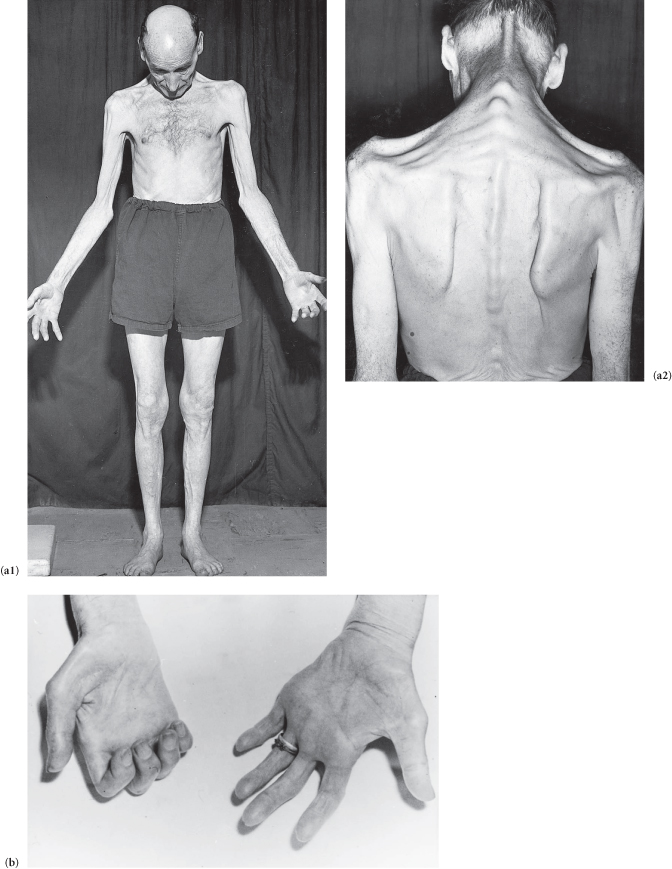

This patient has weakness, wasting and fasciculation of the muscles of the hand (see Station 3, CNS, Case 52), arms and shoulder girdle (progressive muscular atrophy in its pure form is characterized by minimal pyramidal signs), but the upper limb reflexes are exaggerated (reflexes in motor neurone disease may be increased, decreased or absent depending on which lesion is predominant). There is upper motor neurone spastic weakness with exaggerated reflexes in the legs (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis *). There is ankle clonus and the patient has bilateral extensor plantar responses. The patient also has (may have) indistinct nasal speech, a wasted fasciculating tongue and palatal paralysis (progressive bulbar palsy; see Station 3, CNS, Case 21). There are no sensory signs.

The diagnosis is motor neurone disease.

Other Conditions in Which Fasciculation May Occur

Differential Diagnosis of Motor Neurone Disease

Cervical cord compression (see Station 3, CNS, Case 26) is the most important condition to be excluded in the diagnosis of motor neurone disease. Bulbar palsy and sensory signs should be carefully sought, but a cervical MRI scan is often required to exclude it. Syphilitic amyotrophy (slowly progressing wasting of the muscles of the shoulder girdle and upper arm with loss of reflexes and no sensory loss; fasciculation of the tongue may occur) should always be excluded in the investigation of motor neurone disease as it is amenable to treatment. Occasionally patients with old polio, after many years, develop a progressive wasting disease (with prominent fasciculation) which is indistinguishable from progressive muscular atrophy motor neurone disease.

Another condition that needs to be considered is spinal muscular atrophy of juvenile onset type 3 (Kugelberg–Welander disease). This is due to a mutation in the survival motor neurone gene on chromosome 5. The onset is in childhood or in the teen years. It is a milder form of spinal muscular atrophy affecting mostly proximal muscles, but the patients can stand and walk unaided. It can be distinguished from chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy by the presence of normal CSF protein and normal nerve conduction studies.

CNS lymphoma may also present with clinical features suggestive of MND and is an important differential diagnosis to exclude.

Figure C3.8 (a1,2) Generalized muscle wasting (note weakness of the extensors of the neck). (b) Wasting of the small muscles of the hand.

Case 12 | Friedreich’s Ataxia

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

There is pes cavus, (kypho)scoliosis and (may be) a deformed and high-arched palate. The patient is ataxic and clumsy with an intention tremor and his head shakes. There is nystagmus (often slow and coarse and observed before formal examination) and dysarthria (slow and slurred or scanning and explosive). There is (?gross) bilateral impairment of rapid alternate motion, finger–nose and heel–shin tests. Knee and ankle jerks are absent and the plantar responses are extensor. Position and vibration sense are diminished in the feet.

The diagnosis is Friedreich’s ataxia.

Other Features (If Asked)

The condition is one of the hereditary spinocerebellar degenerations. It is an autosomal recessive trinucleotide repeat disorder with a GAA unstable expansion in the long arm of chromosome 9. The fully-fledged syndrome is rare among affected family members who more commonly show slight signs of abnormality in the lower limbs, chiefly pes cavus and absent reflexes (formes fruste).

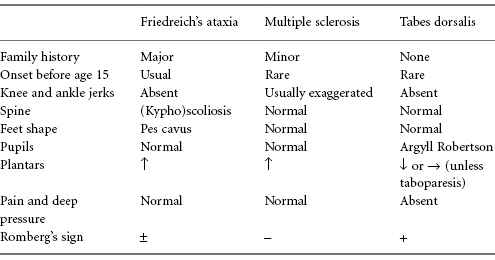

The major classic ataxic conditions which may need to be differentiated from Friedreich’s ataxia, particularly if the latter is mild and presents late, are MS and tabes dorsalis (rare). Typical features which may help to differentiate these conditions are shown in Table C3.4.

Table C3.4 Features which may help to differentiate the major ataxic conditions

Other Conditions Which May have Features of Friedreich’s Ataxia (all are Recessive)

Case 13 | Visual Field Defect

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record 1

There is a homonymous hemianopia. This suggests a lesion of the optic tract behind the optic chiasma (with sparing of the macula and hence normal visual acuity).

Likely Causes

Record 2

There is a bitemporal visual field defect worse on R/L side. This suggests a lesion at the optic chiasma. (NB: There may be optic atrophy, sometimes with a central scotoma, on the R/L side due to simultaneous compression of the optic nerve by the lesion.)

Possible Causes

Rarer causes are glioma, granuloma and metastasis

Record 3

The visual fields are considerably constricted, the central field of vision being spared. This is tunnel vision.* I would like to examine the fundi, looking for evidence of retinitis pigmentosa, glaucoma (pathological cupping) or widespread choroidoretinitis. (Hysteria may occasionally be a cause; papilloedema causes enlargement of the blind spot and peripheral constriction.)

Record 4

There is a central scotoma. (NB: The discs may be pale (atrophy), swollen and pink (papillitis), or normal (retrobulbar neuritis).)

Causes to be Considered

Record 5

There is homonymous upper quadrantic visual field loss. This suggests a lesion in the temporal cortex.

NB: Field defects may sometimes originate from retinal damage, e.g. occlusion of a branch of the retinal artery or a large area of choroidoretinitis.

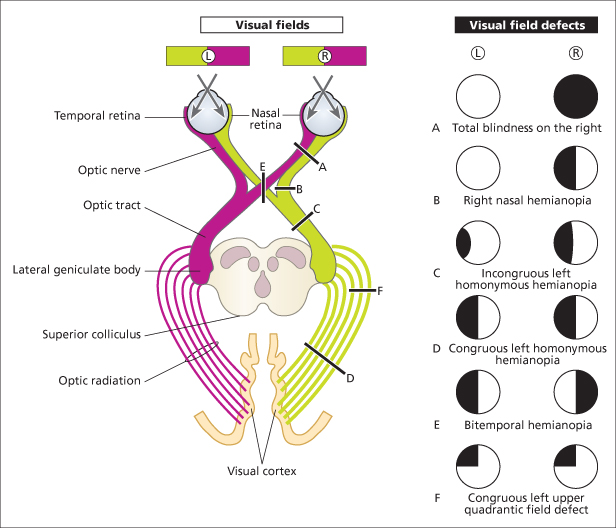

Figure C3.9 The visual pathways and visual field defects resulting from different lesions. If there is exact overlap of the field defects from both eyes, the defect is said to be congruous. If not, it is incongruous. The defects in B and E above are incongruous. Though the complete homonymous hemianopia in D is congruous, lesions of the optic tract (C), which are comparatively rare, produce characteristic incongruous visual changes. The fibres serving identical points in the homonymous half fields do not fully co-mingle in the anterior optic tract so lesions encroaching on this structure produce incongruous and usually incomplete homonymous hemianopias. Lesions of the geniculate ganglia, visual radiations or visual cortex produce congruous visual field defects. F represents a lesion of the temporal loop of the optic radiation.

Case 14 | Ulnar Nerve Palsy

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

The hand shows generalized muscle wasting * and weakness which spares the thenar eminence. There is sensory loss over the fifth finger, the adjacent half of the fourth finger and the dorsal and palmar aspects of the medial side of the hand.† (Look for hyperextension at the metacarpophalangeal joints with flexion of the interphalangeal joints in the fourth and fifth fingers – the ulnar claw hand.)‡

The patient has an ulnar nerve lesion. (Now examine the elbow for a cause.)

Likely Causes

Other Causes

NB: Other causes of wasting of the small muscles of the hand (see Station 3, CNS, Case 52) may sometimes resemble ulnar nerve palsy. The major features pointing to ulnar nerve palsy as the cause are sparing of the thenar eminence and the characteristic sensory loss pattern. The main distinguishing features of the differential diagnoses which may mimic the muscle wasting of ulnar paralysis are:

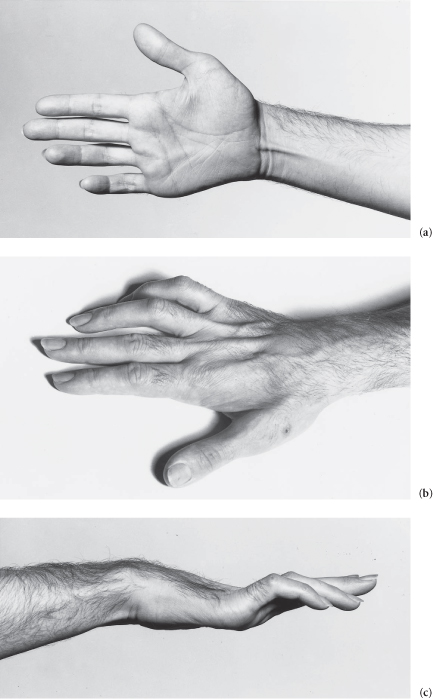

Figure C3.10 (a) Loss of hypothenar eminence. (b) Dorsal guttering. (c) Typical ulnar claw hand.

Case 15 | Old Polio

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

The R/L leg is short, wasted, weak and flaccid with reduced (or absent) reflexes and a normal plantar response. There is no sensory defect. The disparity in the length of the limbs suggests growth impairment in the affected limb since early childhood. The complete absence of sensory and pyramidal signs points to a condition affecting only lower motor neurones.*

The diagnosis is old polio affecting the R/L leg.

If you see one limb smaller than the other, a possible differential diagnosis to consider is infantile hemiplegia. In this, there is usually hypoplasia of the whole of that side of the body and the neurological signs will reflect a contralateral hemisphere lesion (i.e. upper motor neurone).

Figure C3.11 Generalized wasting of the right lower limb due to old poliomyelitis.

Case 16 | Ocular Palsy

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record 1

The patient has a convergent strabismus at rest. There is impairment of the lateral movement of the R/L eye and diplopia is worse on looking to the R/L (the outermost image comes from the affected eye).

The patient has a VIth nerve palsy.

Possible Causes

Record 2

There is ptosis. Lifting the eyelids reveals divergent strabismus and a dilated pupil. The eye is fixed in a down and out position (and there is angulated diplopia).

The diagnosis is complete (NB: the condition is often partial) IIIrd nerve palsy.†

Possible Causes

Other Causes of a IIIrd Nerve Palsy

Other Causes of Ocular Palsy

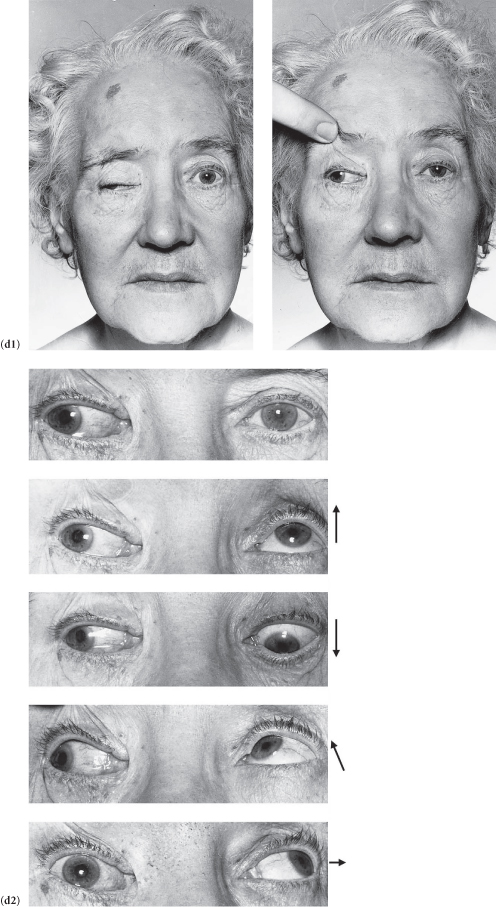

Figure C3.12 (a) Right VIth nerve palsy – diabetic mononeuritis. (1) Patient looking straight ahead (note convergent strabismus); (2) looking to the right. (b1,2) Left IIIrd nerve palsy (note ptosis and mydriasis of the left pupil). The patient had had surgery for a pituitary tumour (note scar on upper forehead and left frontal alopecia). (c) Upward gaze being tested (note the failure of the left eye to follow the examiner’s finger). (d) (Opposite) Complete right IIIrd nerve palsy: (1) note mydriasis of the right pupil and the down and outward deviation of the right eye (due to the unopposed action of the superior oblique and lateral rectus muscles innervated by the IVth and VIth nerves, respectively); (2) testing eye movements (note the failure of the right eye to look straight, upwards, downwards, upwards and laterally, and medially).

Case 17 | Spinal Cord Compression*

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record 1

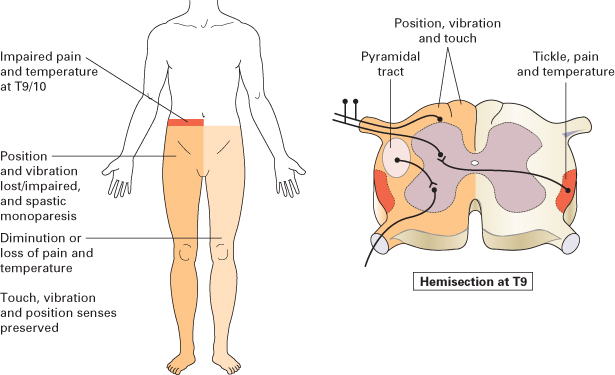

This patient (who complains of difficulty in walking) has a monoparesis of the R/L leg with hypertonia, muscular weakness without wasting, hyperreflexia and an extensor plantar response. There is loss of joint position and vibration senses on the side of the monoparesis and loss of pain and temperature senses on the opposite side below the level (determine the upper limit of the sensory loss) of (e.g.) T8–9 segments.

These features suggest a diagnosis of the Brown–Séquard syndrome resulting from hemisection of the spinal cord. Among the causes are injury, tumour, late myelopathy from radiation therapy and multiple sclerosis.

Record 2

There is muscular weakness in both legs, more on the R/L side with hypertonia, hyperreflexia (?clonus) and bilateral extensor plantars. Soft touch and pinprick sensations are diminished in both legs extending upwards to the level of (e.g.) T8 segment.† Joint position and vibration senses are intact. There is no neurological abnormality in the upper limbs.

These findings, together with your opening statement that this patient has had a recent onset of back pain, suggest spinal cord compression, possibly from a tumour or intervertebral disc prolapse at T7–8 level. This will need to be urgently investigated.

Record 3

The skin over the R/L buttock is loose and droopy due to wasting of the underlying glutei. The corresponding calf muscles are flabby, with weakness of plantar flexion at the ankle joint. The patient is unable to stand on his toes and the ankle jerk is absent on the affected side. The sensation is impaired along the outer border of the foot and the outer half of the sole.

Since you said that the patient has a spinal disc problem, I would suggest that he has had herniation of the fifth lumbar disc compressing the S1 root.‡

Causes of Spinal Cord and Root Compression

Diseases of the Vertebrae and Discs

Tumours

Vascular

Inflammatory Disorders

Diagnosis

The diagnosis depends on the history (trauma, malignancy, pain in the spine, sometimes with a radicular distribution and aggravated by straining and coughing, weakness of the legs and arms and sphincter disturbance), a neurological examination and, in urgent cases, CT or MRI. Diseases of the vertebrae and discs can be diagnosed from history, examination and a plain film of the spine.

Back pain or neck pain should be taken seriously in a patient with a known malignancy. The pain of intraspinal lesions is exacerbated by straining, sneezing, coughing and movement. Unless investigated and treated early, midline pain progresses to radicular pain and is followed by weakness, sensory loss and sphincter disturbance. Patients who have neurological signs of cord compression require immediate treatment with dexamethasone and emergency evaluation.

About 60–80% of patients with spinal cord compression will show erosion or loss of the pedicles, vertebral body destruction or collapse or a paraspinal mass on plain film. However, plain X-ray is hardly ever useful in suspected cord compression.

All patients with suspected spinal cord/nerve root compression should have an MRI scan of the corresponding region of the spine. If MRI is contraindicated (please note, most of the newer intracranial clips, prostheses, etc. are MR compatible), a CT myelogram might be an alternative choice. Suspected spinal cord compression is a neurological emergency.

Figure C3.13 The Brown–Séquard syndrome.

(After Mir MA. Atlas of Clinical Skills, 1997, by kind permission of the author and the publisher, WB Saunders.)

Case 18 | Ptosis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

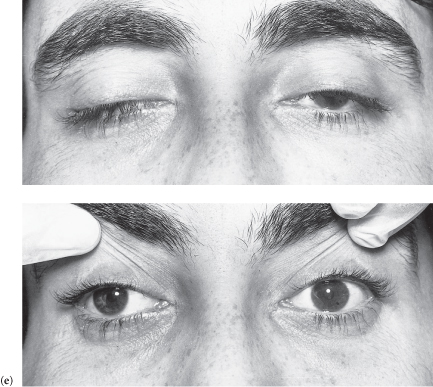

Record 1

There is unilateral ptosis.*

Possible Causes

Record 2

There is bilateral ptosis.*

Possible Causes

Other Causes of Ptosis

Figure C3.14 (a) Third nerve palsy: complete ptosis. (b) Right Horner’s syndrome. (c) Myasthenia gravis: bilateral, asymmetrical ptosis. (d) Myotonic dystrophy: sustained contraction of the lingual muscles after percussion on the tongue plus bilateral ptosis. (e) Ocular myopathy.

Case 19 | Guillain–Barré Syndrome (Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculopathy)

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 1% of attempts at PACES Station 3, CNS.

Record

This (most commonly) young adult has a predominantly motor neuropathy. The weakness is more marked distally* and there is generalized hyporeflexia. There is a lower motor neurone facial weakness (often bilateral) and evidence of bulbar palsy. There is (may be) mild impairment of distal position and vibration perception and slight loss of pinprick sensation over the toes.† The patient has a tachycardia.‡

These features suggest Guillain–Barré syndrome (acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy; AIDP).

Features of AIDP

There is an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection or gastrointestinal illness (e.g. Campylobacter jejuni) within 1 month in 60%§ of cases.

There is a bimodal age distribution – main peak in young adults, lesser peak in 45–64-year age group.

Cerebrospinal fluid protein is usually normal during the first 3 days; it then steadily rises and may continue to rise even though recovery has begun; it may exceed 5 g L−1. A few mononuclear cells may be present in the CSF (<10 mm−3).

Mortality is 5%. The apparently mild case may worsen rapidly and unpredictably. Vital capacity (peak flow rate measurement is irrelevant), blood gases, blood pressure and ability to cough and swallow should be closely monitored; if mechanical ventilation is anticipated from the results then it should be instituted early, before decompensation.

Paralysis is maximum within 1 week in more than 50% of cases and by 1 month in 90%. Recovery usually begins 2–4 weeks later.¶ Rate of recovery is variable, occasionally rapid even after quadriplegia. Eighty-five percent of patients are ambulatory within 6 months. Mild residual peripheral nervous system damage occurs in 50%.

Plasmapheresis in the first 2 weeks shortens the clinical course and reduces morbidity. Intravenous immunoglobulin in the first 2 weeks is an alternative therapy that has equivalent efficacy to plasmapheresis, and is now the treatment of choice.

Some patients present with rapid onset of symmetrical, multiple cranial nerve palsies, most notably bilateral facial palsy (polyneuritis cranialis). Occasionally, there may be a combination of an external ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and areflexia (Miller–Fisher syndrome) associated with high CSF protein and some motor weakness. Serum IgG antibodies to GQ1b ganglioside are found in acute-phase sera of over 90% of Miller–Fisher syndrome patients. They disappear during recovery.

Most patients achieve good recovery from AIDP. The importance of fastidious supportive care during the acute stage cannot be overstressed.

Figure C3.15 External ophthalmoplegia in the Miller–Fisher syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree