Case 3 | Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema*

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 11% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Survey Note:

usually the patients in the examination fall between the extremes of the classic Records below.

Record 1

This thin man (with an anxious, drawn expression) presents the classic ‘pink puffer’ appearance. He has nicotine staining of the fingers. He is tachypnoeic at rest with lip pursing during expiration, which is prolonged. The suprasternal notch to cricoid distance is reduced (a sign of hyperinflation; normally >3 finger breadths). His chest is hyperinflated, expansion is mainly vertical and there is a tracheal tug. He uses his accessory muscles of respiration at rest and there is indrawing of the lower ribs on inspiration (due to a flattened diaphragm). The percussion note is hyperresonant, obliterating cardiac and hepatic dullness, and the breath sounds are quiet (this is so in classic pure emphysema – frequently, though, wheezes are heard due to associated bronchial disease).

These are the physical findings of a patient with emphysema (inspiratory drive often intact).†

Record 2

This (male) patient (who smokes, lives in a foggy city, works amid dust and fumes, and has probably had frequent respiratory infections) presents the classic ‘blue bloater’ appearance. He has nicotine staining on the fingers. He is stocky and centrally cyanosed with suffused conjunctivae. His chest is hyperinflated, he uses his accessory muscles of respiration; there is indrawing of the intercostal muscles on inspiration and there is a tracheal tug (both signs of hyperinflation). His pulse is 80/min, the venous pressure is not elevated (may be raised with ankle oedema and hepatomegaly if cor pulmonale is present), the trachea is central, but the suprasternal notch to cricoid distance is reduced. Expansion is equal but reduced to 2 cm and the percussion note is resonant; on auscultation, the expiratory phase is prolonged and he has widespread expiratory rhonchi and (may be) coarse inspiratory crepitations. (His forced expiratory time (see Section B, Examination Routine 3) is 8 sec.) There is no flapping tremor of the hands (unless he is in severe hypercapnoeic respiratory failure in which case ask to examine the fundi – ?papilloedema).

These are the physical findings of advanced chronic bronchitis‡ (inspiratory drive often reduced) producing chronic small airways obstruction (and, if ankle oedema, etc., right heart failure due to cor pulmonale).

Causes of Emphysema

Record 1 (Continuation)

The decreased breath sounds over the … zone of the R/L lung of this patient with emphysema raises the possibility of an emphysematous bulla.

Investigations Include:

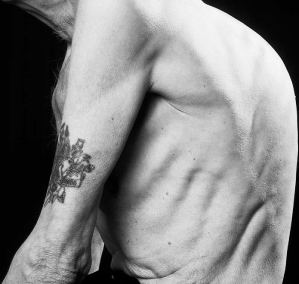

Figure C1.2 Hyperinflated rib cage. Note indrawing of intercostal muscles.

Case 4 | Bronchiectasis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 9% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Record

This patient (who may be rather underweight, breathless and cyanosed) has clubbing of the fingers (not always present) and a frequent productive cough (the patient may cough in your presence;* there may be a sputum pot by the bed). There are (may be) inspiratory clicks heard with the unaided ear. There are crepitations over the … zone(s) (the area(s) where the bronchiectasis is) and (may be) widespread rhonchi.

The diagnosis could well be bronchiectasis. The frequent productive cough and inspiratory clicks are in favour of this. Other possibilities (clubbing and crepitations) are:

Possible Causes of Bronchiectasis

Investigations Include

Case 5 | Dullness at the Lung Base

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 7% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Record

The pulse is regular and the venous pressure is not elevated. The trachea is central,* the expansion is normal, but the percussion note is stony dull at the R/L base(s), with diminished tactile fremitus and vocal resonance, and diminished breath sounds. There is (may be) an area of bronchial breathing above the area of dullness.

The diagnosis is R/L pleural effusion.†

Causes of Pleural Effusion

Other Causes of Pleural Effusion

Other Causes of Dullness at a Lung Base

Pleural Biopsy

Biopsy is carried out using an ‘Abram’s biopsy needle’. The specificity for detecting TB and malignancy is better with a pleural biopsy than with a pleural aspiration on its own. Remember that any biopsies for TB cultures should be placed in normal saline and not formalin.

Thoracoscopy

This is a technique involving visual inspection of the pleural cavity for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes (e.g. pleurodesis).

Case 6 | Rheumatoid Lung

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 4% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Record

There is (may be) cyanosis (there may also be dyspnoea) and the principal finding in the chest is of fine inspiratory crackles (or crepitations – whichever term you prefer) on auscultation at both bases.

In view of the rheumatoid changes (see Vol. 3, Station 5, Locomotor, Case 1) in the hands (there may also be clubbing), the likely diagnosis is pulmonary fibrosis associated with rheumatoid disease (rheumatoid lung).

Classic fibrosing alveolitis develops in 2%* of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and has a poor prognosis. It may progress to a honeycomb appearance on chest X-ray, bronchiectasis, chronic cough and progressive dyspnoea. Pulmonary function tests show reduced diffusion capacity, diminished compliance and a restrictive ventilatory pattern.

Gold, used in the therapy of rheumatoid arthritis, can also induce interstitial lung disease; it is indistinguishable from rheumatoid pulmonary fibrosis except that the gold-induced disease may reverse when the drug is discontinued.

Other Pulmonary Manifestations of Rheumatoid Disease

Pleural disease. † Though frequently found at autopsy, rheumatoid pleural disease is usually asymptomatic. The rheumatoid patient may have a pleural rub or pleural effusion but only occasionally would the latter be of sufficient size to cause respiratory limitation. The pleural fluid at diagnostic aspiration is never blood- stained and often contains immune complexes and rheumatoid factor; it is high in protein (exudate) and LDH and low in glucose, C3 and C4. The white count in the pleural fluid is variable but usually <5000/µL.

Intrapulmonary nodules. Single or multiple radiological nodules may be seen in the lung parenchyma before or after the onset of arthritis. They are usually asymptomatic but may become infected and cavitate. As they have a predilection for the upper lobes and can cause haemoptysis, they can resemble tuberculosis or even carcinoma. They can rupture into the pleural space, causing a pneumothorax. Massive confluent pulmonary nodules may be seen in rheumatoid lungs in association with pneumoconiosis (Caplan’s syndrome).

Obliterative bronchiolitis. Rarely, small airways obstruction may develop into a necrotizing bronchiolitis, classically associated with dyspnoea, hyperinflation and a high-pitched expiratory wheeze or ‘squawk’ on auscultation. This complication may also result from therapy with gold or penicillamine.

Two other manifestations are pulmonary arteritis (reminiscent of polyarteritis nodosa) and apical fibrobullous disease.

Case 7 | Old Tuberculosis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Record 1

The trachea is deviated to the R/L. The R/L upper chest shows deformity with decreased expansion, dull percussion note, bronchial breathing and crepitations. The apex beat is (may be) displaced to the R/L. There is a thoracotomy scar posteriorly with evidence of rib resections.

The patient has had a R/L thoracoplasty for treatment of tuberculosis before the days of chemotherapy.

Record 2

The tracheal deviation to the R/L and the diminished expansion and crackles at the R/L apex suggest R/L apical fibrosis.

Old tuberculosis is the likely cause.

Record 3

Expansion is diminished on the R/L with dullness and reduced/absent breath sounds at the R/L lung base. There is a R/L supraclavicular scar (there may also be crepitations).

The patient has had a phrenic nerve crush for TB before the days of chemotherapy.

Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis*

First 2 months (intensive phase†):

Four-month continuation phase:

Case 8 | Chest Infection/Consolidation/Pneumonia

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Record

There is reduced movement of the R/L side of the chest. There is dullness to percussion over … (describe where) with bronchial breathing, coarse crepitations, whispering pectoriloquy and a pleural friction rub.

These features suggest consolidation (say where).

Most Common Causes of Consolidation

Bacterial pneumonia (pyrexia, purulent sputum, haemoptysis, breathlessness)

Carcinoma (with infection behind the tumour; ?clubbing, wasting, etc; see Station 1, Respiratory, Case 13)

Pulmonary infarction (fever less prominent, sputum mucoid, occasionally haemoptysis and blood-stained pleural effusion)

Causes of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Hospital Studies*

| Microbe | Percentage |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 39 |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 13.1 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 10.8 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 5.2 |

| Legionella spp | 3.6 |

| Chlamydia psittaci | 2.6 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1.9 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 1.9 |

| All viruses | 12.8 |

Investigations May Include

The CURB-65 Score

One or fewer of the above is associated with a low mortality (1.5%) and perhaps suitability for home treatment, whereas three or more features are suggestive of a severe pneumonia with a higher mortality (22%) and the advisability of consideration of ICU support.

Case 9 | Yellow Nail Syndrome

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Survey Note:

see Vol. 2, Section F, Anecdotes 89 and 90.

Yellow nail syndrome is dealt with in Vol. 3, Station 5, Skin, Case 12.

Case 10 | Kyphoscoliosis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Survey Note:

see Vol. 2, Section F, Anecdotes 91 and 92.

Record

On inspection of the chest from the side (of this patient whom you have been told has been referred for investigation of breathlessness), I note an increase in thoracic curvature. There is no suggestion of any prominent angular features indicative of a gibbus and no evidence of any reversal of the normal lumbar lordosis. Further inspection of the patient when bending forwards shows restriction in the mobility of the spine. Inspection of the back shows no evidence of neurofibromatosis, spina bifida (hairy patch), thoracotomy scars, or spinal surgery scars. Whilst sitting down and bending forwards, the curvature remains, suggesting that the scoliosis is fixed. There is a rib hump. Palpation of the spine reveals no tenderness. Sliding the fingers down the spine reveals no evidence of a palpable step at the lumbo-sacral junction (feature of spondylolisthesis). Whilst the patient is standing, he demonstrates that he cannot touch his toes on flexion, and there is reduced extension when asked to bend back, whilst keeping the pelvis steady. There is evidence of reduced lateral flexion and rotation. There are no other features suggestive of old poliomyelitis or any obvious muscle atrophy in any of the limbs. The patient is (may be) cyanosed. Chest expansion is reduced but percussion and breath sounds are normal.

The patient demonstrates a scoliosis, most likely idiopathic in origin. The breathlessness is likely to be due to hypoventilation secondary to the deformity.

Scoliosis is a lateral curvature of the spine. Deformity of the spine will suggest a structural scoliosis rather than a non-structural scoliosis where the vertebrae are normal and the curvature can be due to compensatory reasons, e.g. tilting of the pelvis, sciatic due to unilateral muscle spasm or postural. In structural scoliosis, the deformity cannot be altered by a change in posture.

Kyphosis is the term used to describe the increased forward curvature. Therefore kyphoscoliosis describes an abnormal curvature of the spine in both coronal and sagittal planes. There may be varying degrees of kyphosis and scoliosis in an individual patient.

Causes of Kyphoscoliosis Include

Prognosis depends on age of onset, the level of the spine affected (the higher the level, the worse the prognosis), the number of primary curves, the type of structural scoliosis (congenital versus idiopathic).

Causes of Kyphosis only Include

Investigations Include

X-ray of spine and chest – concavity, with displacement of the spine and narrowing of the pedicles. On convexity there will be widening of the rib spaces. Angular deformity can be measured more accurately using the Cobb method*

MRI of the spine may be considered to look at the spinal cord

Spirometry – restrictive picture with a reduced FEV1 and FVC. FVC of under 1 L will increase the risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure secondary to hypoventilation

Non-Invasive Ventilation

The need for domiciliary NIV should be assessed in the presence of breathlessness, poor sleep quality, and type II respiratory failure from blood gas analysis. Long-term follow-up by NIV specialists is necessary. Pulmonary hypertension is common in untreated respiratory failure.

Case 11 | Stridor

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 1% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Record

The patient is comfortable at rest. From the bedside I can hear a noisy, high-pitched sound with each inspiration. Her respiratory rate is 12/min. Chest expansion is normal, resonance is normal and auscultation reveals normal vesicular breath sounds and no added sounds. There is (may be) a healed tracheostomy scar present.

In view of the tracheostomy scar, it is likely that the inspiratory stridor is due to tracheal stenosis following prolonged ventilatory support via a tracheostomy.

Inspiratory stridor usually implies upper airways obstruction and tracheal narrowing (extrathoracic).

Causes of Inspiratory Stridor

Expiratory stridor is usually found with lower intrathoracic obstruction.

Causes of Expiratory Stridor

Causes of Tracheal Stenosis

Management would include referral to thoracic surgeon who would consider rigid bronchoscopy with possible dilation and/or stent insertion. Primary reconstruction may be considered as definitive treatment.

Case 12 | Marfan’s Syndrome

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 1% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Survey Note:

see Vol. 2, Section F, Experience 27 and Anecdote 88.

Marfan’s syndrome is dealt with in Vol. 3, Station 5, Locomotor, Case 9.

Case 13 | Carcinoma of the Bronchus

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 0.8% of attempts at PACES Station 1, Respiratory.

Survey Note:

candidates reported a variety of signs. The three records given are typical.

Record 1

There is clubbing of the fingers which are nicotine-stained. There is a hard lymph node in the R/L supraclavicular fossa. The pulse is 80/min and regular, and the venous pressure is not raised. The trachea is central, chest expansion normal, but the percussion note is stony dull at the R/L base and tactile fremitus, vocal resonance and breath sounds are all diminished over the area of dullness.

The likely diagnosis is carcinoma of the bronchus causing a pleural effusion.

Record 2

The patient is cachectic. There is a radiation burn on the R/L upper chest wall. There is clubbing of the fingers which are nicotine-stained. The pulse is 80/min, venous pressure is not elevated and there are no lymph nodes. The trachea is deviated to the R/L and expansion of the R/L upper chest is diminished. Tactile vocal fremitus and resonance are increased over the upper chest where the percussion note is dull and there is an area of bronchial breathing.

It is likely that this patient has had radiotherapy for carcinoma of the bronchus which is causing collapse and consolidation of the R/L upper lung.

Record 3

There is a radiation burn on the chest. There are lymph nodes palpable in the R/L axilla. The trachea is central. I did not detect any abnormality in expansion, vocal fremitus, vocal resonance or breath sounds, but there is wasting of the small muscles of the R/L hand, and sensory loss (plus pain) over the T1 * dermatome. There is a R/L Horner’s syndrome (see Station 3, CNS, Case 41).

The diagnosis is Pancoast’s syndrome (due to an apical carcinoma of the lung involving the lower brachial plexus and the cervical sympathetic nerves).

Other Complications of Carcinoma of the Bronchus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree