Linda Y. North

Care of the patient with an integumentary disorder

Objectives

1. Discuss the primary functions of the integumentary system.

2. Describe the differences between the epidermis and dermis.

3. Discuss the functions of the three major glands located in the skin.

4. Discuss the general assessment of the skin.

5. Discuss the viral disorders of the skin.

6. Discuss the bacterial, fungal, and inflammatory disorders of the skin.

7. Identify the parasitic disorders of the skin.

8. Describe the common tumors of the skin.

9. Identify the disorders associated with the appendages of the skin.

10. State the pathophysiology involved in a burn injury.

11. Identify the methods used to classify the extent of a burn injury.

12. Discuss the stages of burn care with appropriate nursing interventions.

13. Discuss how to use the nursing process in caring for patients with skin disorders.

14. Identify general nursing interventions for the patient with a skin disorder.

Key terms

alopecia ( l-

l- -P

-P -sh

-sh –

– , p. 94)

, p. 94)

autograft ( W-t

W-t -gr

-gr ft, p. 100)

ft, p. 100)

contracture (k n-TR

n-TR K-ch

K-ch r, p. 98)

r, p. 98)

Curling’s ulcer (K R-l

R-l ngz

ngz  L-s

L-s r, p. 98)

r, p. 98)

excoriation ( ks-k

ks-k r-

r- –

– -sh

-sh n, p. 72)

n, p. 72)

heterograft (xenograft) (H T-

T- r-

r- -gr

-gr ft; Z

ft; Z -n

-n -gr

-gr ft, p. 100)

ft, p. 100)

homograft (allograft) (H -m

-m -gr

-gr ft;

ft;  L-

L- -gr

-gr ft, p. 100)

ft, p. 100)

pediculosis (p -d

-d k-

k- -L

-L -s

-s s, p. 87)

s, p. 87)

pruritus (proo-R -t

-t s, p. 61)

s, p. 61)

pustulant vesicles (P S-t

S-t -l

-l nt V

nt V S-

S- -k

-k lz, p. 76)

lz, p. 76)

suppuration (s p-

p- -R

-R -sh

-sh n, p. 77)

n, p. 77)

urticaria ( r-t

r-t -K

-K -r

-r –

– , p. 81)

, p. 81)

The skin, or integument is a major organ and the outer covering of the body. Together with its appendages—hair, nails, and special glands—it makes up the integumentary system. Skin is essential to life. Society has long held healthy skin in high esteem, probably because it is so visible to others. People spend many hours grooming their hair, cleansing their skin, and manicuring their nails. But beyond its social aspect, the integument is the body’s protector, its first line of defense against infection and injury.

Anatomy and physiology of the skin

Functions of the skin

Although the skin covers the outside of the body, its main function is homeostasis and protection of the internal organs. Each day it is subjected to temperature and humidity changes, trauma, ecchymosis, abrasions, contact with pathogens, and wear and tear. The skin carries out the numerous functions to protect and maintain the body (Box 3-1).

Protection

Sensory receptors within the skin receive information about the environment. Messages about heat, cold, pressure, and touch are received and relayed to the central nervous system for interpretation. Healthy skin protects the body from absorbing many chemicals and foreign substances. Additionally, as long as it remains intact, skin provides a barrier to many microorganisms in the environment. Internal organs are cushioned and protected by a subcutaneous layer of adipose (fat) tissue. The skin aids in elimination of waste products, prevents dehydration, and serves as a reservoir for food and water.

Temperature regulation

Skin assists the body in maintaining a constant temperature under varying internal and external conditions. It allows blood vessels near the surface to constrict when the environment is cold to preserve heat and allows them to dilate when it is hot to release excess body heat. Sweat glands release moisture, which cools the body as it evaporates. A layer of adipose tissue works as an insulator by retaining heat.

Vitamin D synthesis

Cholesterol compounds in the skin are converted to vitamin D when exposed to the sun’s ultraviolet rays. Vitamin D is necessary for healthy bone development. Prolonged exposure to the sun’s rays, which is ultraviolet radiation, should be avoided because of the increased risk of developing skin cancer.

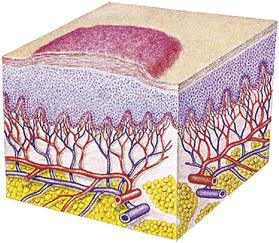

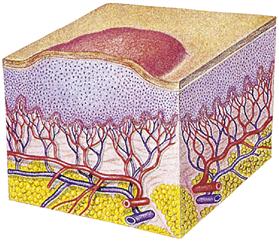

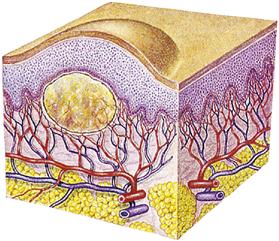

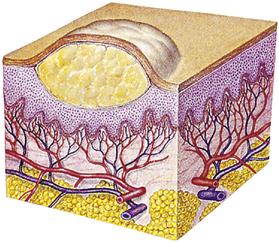

Structure of the skin

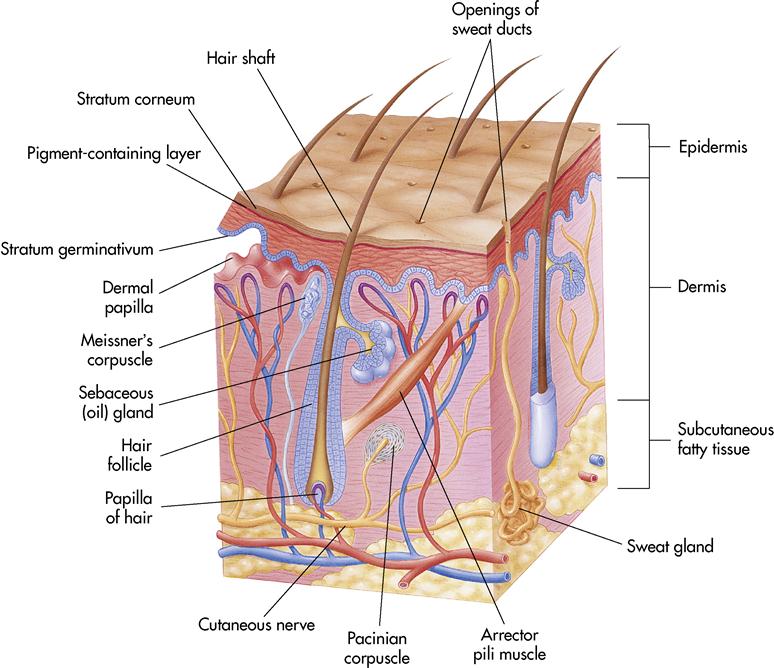

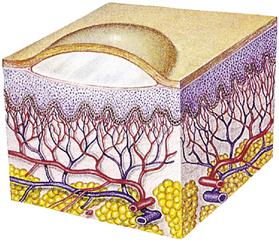

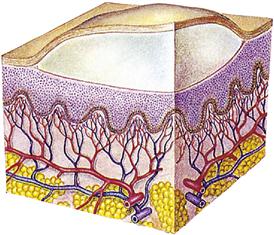

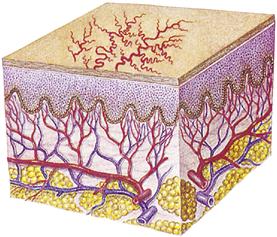

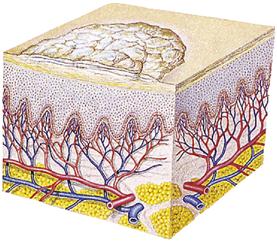

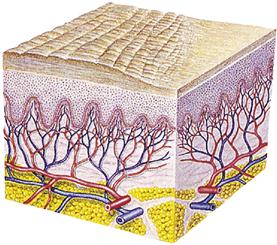

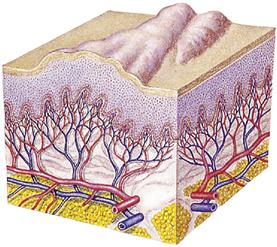

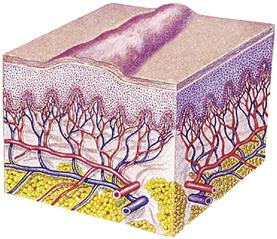

Skin consists of two layers: the outer epidermis and inner dermis, or corium. Beneath these layers of skin lies the subcutaneous layer, or superficial fascia (Figure 3-1).

Epidermis

The epidermis, the superficial fascia (avascular layers of the skin), is composed of stratified squamous (from the Latin squama, meaning “scale”) epithelium. The cells of the epidermis are tightly packed and have no distinct blood supply. The epidermis is divided into layers, or strata: an outer, dead, cornified portion and a deep, living, cellular portion. The inner layer is called the stratum germinativum; it is the only layer of the epidermis able to undergo cell division and reproduce itself. It receives its blood supply and nutrition from the underlying dermis through a process called diffusion. This provides a constant new supply of cells for the upper layers and enables the skin to repair itself after injury. As these cells push their way to the surface, their internal structures are destroyed and the cells die. When they reach the outermost layer, called the stratum corneum, they are flat and the cell structure is filled with a protein called keratin (horn). The stratum corneum is sometimes called the horny layer. The keratin makes the cells dry, tough, and somewhat waterproof.

Another layer in the epidermis contains highly specialized cells called melanocytes. These cells give rise to the pigment melanin, a black or dark brown pigment occurring naturally in the hair, the skin, and the iris and choroid of the eye. Melanin is responsible for the skin’s color. The greater the concentration of melanin, the darker the skin. Sometimes irregular patches with greater concentrations of melanin occur, producing freckles. The amount of melanin a person has is inherited from the parents. Although skin color is inherited, exposure to the sun and other factors can influence skin color.

Dermis

The dermis, or corium, is often called the true skin. It is well supplied with blood vessels and nerves and also contains glands and hair follicles. It varies in thickness throughout the body but tends to be thickest in the palms and soles. The dermis is composed of connective tissue with cells scattered among collagen and elastic fibers. The dermis receives strength from the collagen and flexibility from the elastic connective fibers. The cells throughout this layer are bathed in tissue fluid called interstitial fluid. The skin wrinkles with the normal aging process, as the dermis loses some of its elastic connective fibers and the subcutaneous tissue directly beneath it loses some of its adipose tissue. Located in the upper portion of the dermis are small fingerlike projections called papillae that project into the lower epidermal layer. Without the dermal papillae, the epidermal layer would be unable to survive.

Subcutaneous layer

The subcutaneous layer, sometimes called the superficial fascia, is the layer of tissue directly beneath the dermis that connects the skin to the muscle surface. This layer is composed of adipose tissue and loose connective tissue. It serves several important functions: (1) stores water and fat, (2) insulates the body, (3) protects the organs lying beneath it, and (4) provides a pathway for nerves and blood vessels. The distribution of subcutaneous tissue throughout the body provides shape and contour. A woman’s body usually contains more subcutaneous tissue than a man’s; thus her body is softer and more rounded.

Appendages of the skin

Sudoriferous glands

The sudoriferous (sweat) glands are coiled, tubelike structures located in the dermis and subcutaneous layers. The tubes open into pores on the skin surface. Approximately 3 million sweat glands are located throughout the integumentary system. These glands excrete sweat, which cools the body’s surface. Sweat is composed of water, salts, urea, uric acid, ammonia, sugar, lactic acid, and ascorbic acid.

Ceruminous glands

Ceruminous glands are modified sudoriferous glands. They secrete a waxlike substance called cerumen and are located in the external ear canal. Cerumen is thought to protect the canal from foreign body invasion.

Sebaceous glands

The sebaceous (oil) glands secrete sebum (an oily secretion) through the hair follicles distributed on the body. Their function is to lubricate the skin and hair that covers the body. Sebum also inhibits bacterial growth.

Hair and nails

Hair is composed of modified dead epidermal tissue, mainly keratin. It is distributed all over the body in varying amounts. The root of the hair is enclosed in a follicle deep in the dermis. The shaft of the hair protrudes from the skin. Surrounding the hair follicle is a band of muscle tissue called arrector pili (see Figure 3-1). A sensation of cold or fear causes these muscles to contract, making the hair stand upright and dimpling the skin surrounding it. The effect is called piloerection, or “gooseflesh.”

Nails are also composed mainly of keratin, but the keratin is more compressed. The base of the nail, the root, is made up of living cells and is mostly covered by the cuticle. Part of the root, the lunula, is exposed and looks like a white crescent. The remainder of the nail is called the nail body. It appears pink because of the blood vessels lying immediately beneath it.

Assessment of the skin

Inspection and palpation

A thorough assessment of the skin helps identify many diseases that result from an outside organism penetrating the skin. However, remember that recognizing skin conditions by inspection takes time and experience.

Begin the assessment by obtaining a careful health history from the patient. Ask the patient about (1) recent skin lesions or rashes, (2) where the lesions first appeared, and (3) how long the lesions have been present. Also ask about a personal or family history of asthma, seasonal rhinitis, or drug allergies. Explore all complaints of pain, pruritus (the symptom of itching), tingling, or burning. Ask the patient about personal skin care and about (1) any recent skin color changes: (2) exposure to the sun, with or without sunscreen: and (3) family history of skin cancer.

Assess the skin under natural lighting, and use the senses of sight, touch, and smell while inspecting and palpating the skin. Expose the area to be assessed while maintaining privacy. Remember to wear gloves when inspecting the skin, mucous membranes, and any involved area. In the hospital, the morning bath provides an excellent opportunity to assess the patient’s skin without exposure or embarrassment.

Observe the color of the skin. The color depends on many physiologic factors, including the following:

• Amount of hemoglobin in the blood

• Oxygen saturation in the blood

• Amount of substances such as bilirubin, urea, or other chemicals in the blood

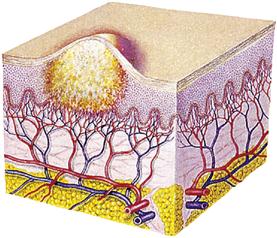

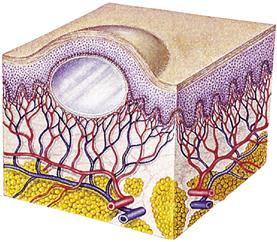

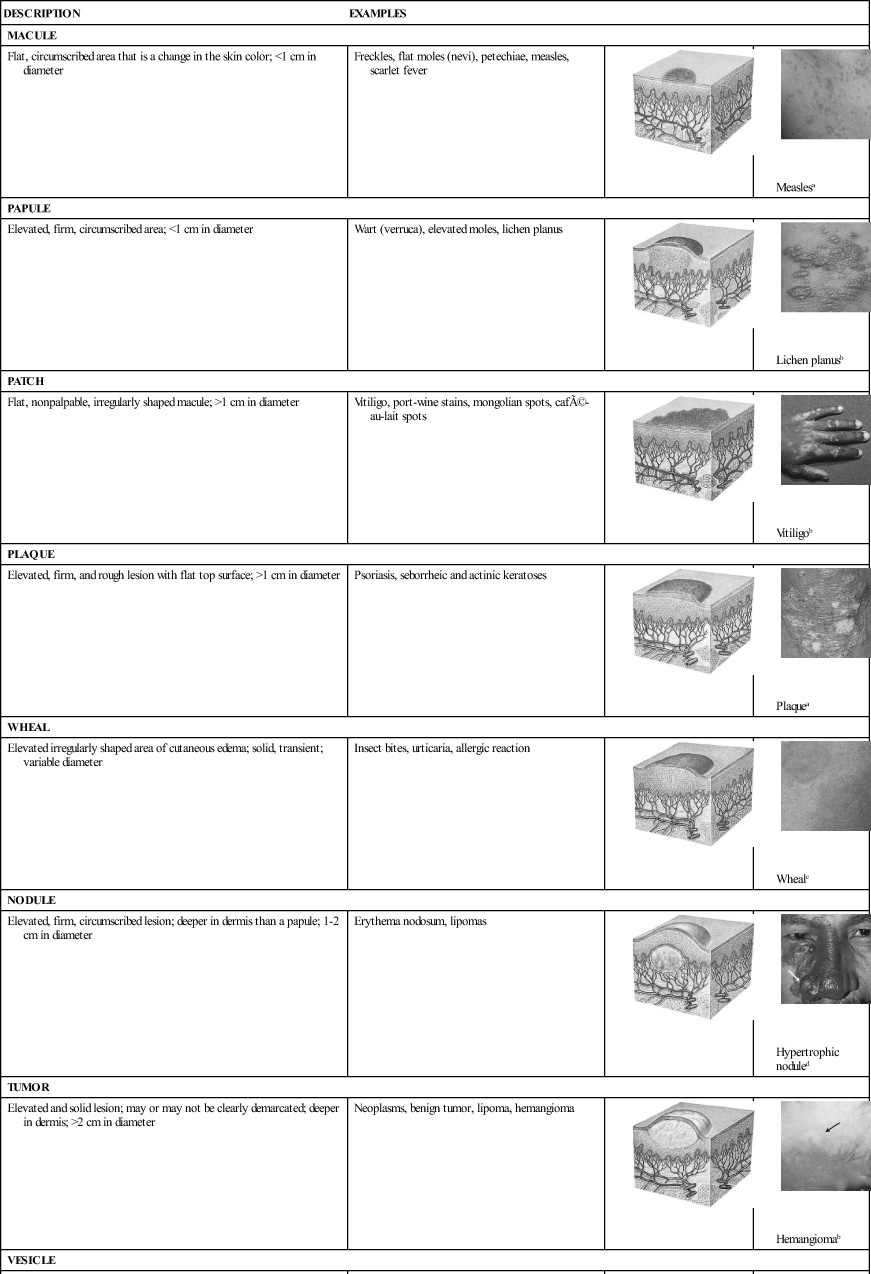

Assessment of specific skin lesions, their appearance, and their location assists the dermatologist in diagnosing skin disorders and the nurse in providing care. Most disorders have only one or two types of lesions. Some of the typical clinical manifestations of skin disorders are shown in Table 3-1.

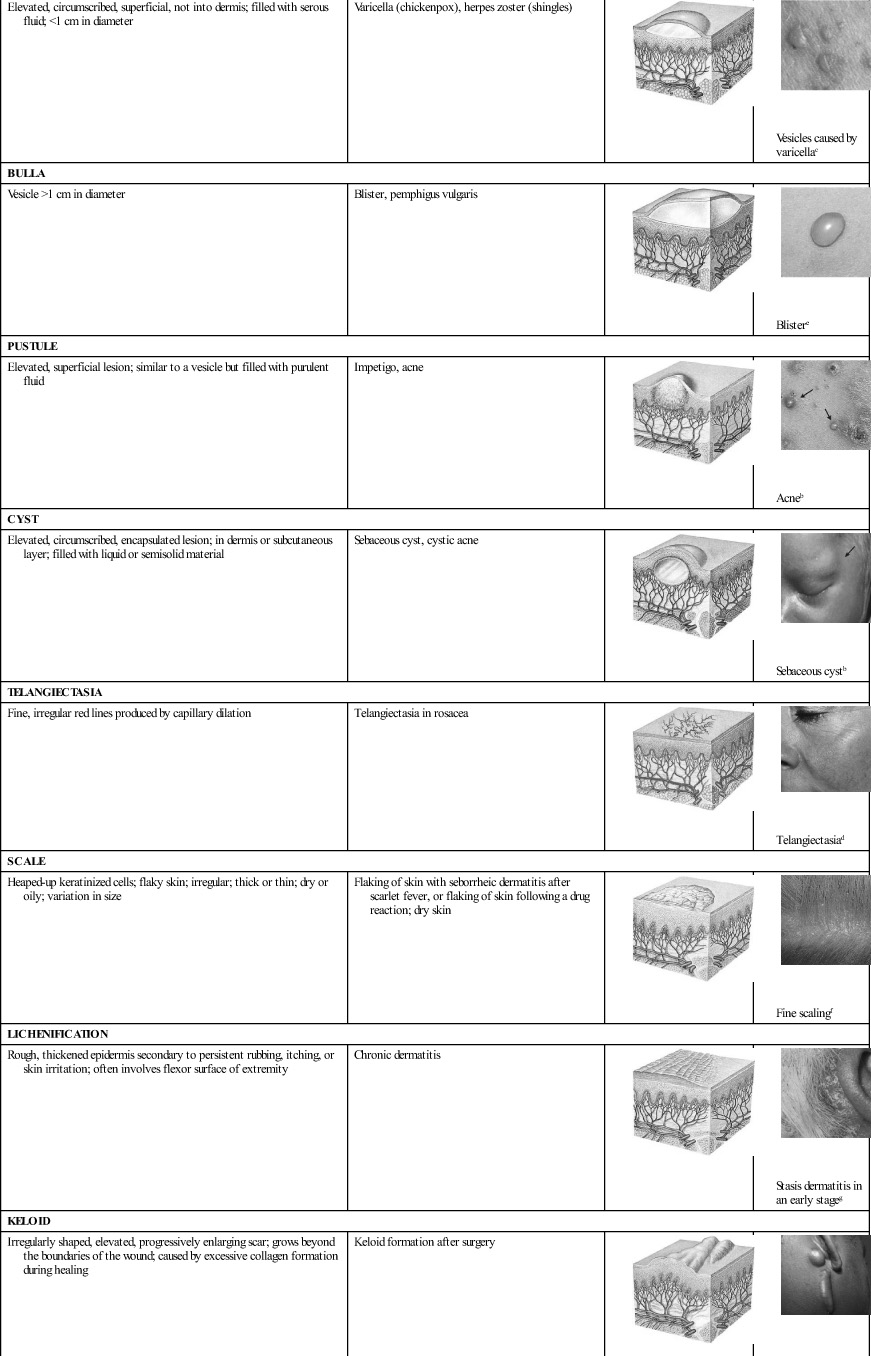

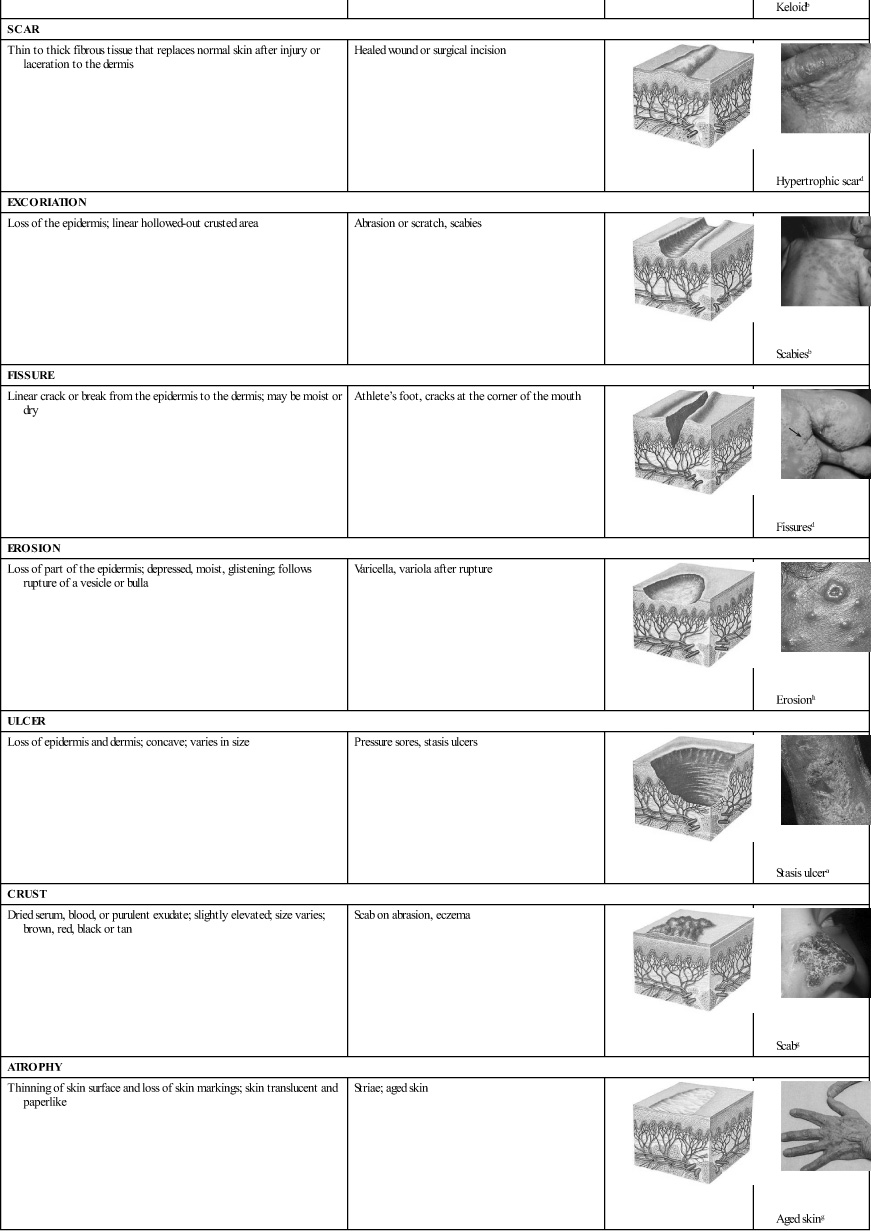

Table 3-1

| DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLES | ||

| MACULE | |||

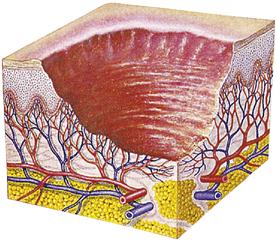

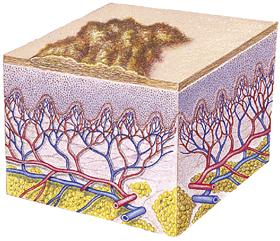

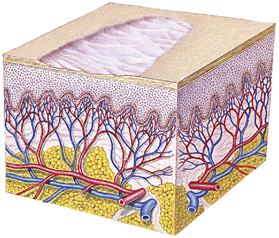

| Flat, circumscribed area that is a change in the skin color; <1 cm in diameter | Freckles, flat moles (nevi), petechiae, measles, scarlet fever |  |  Measlesa |

| PAPULE | |||

| Elevated, firm, circumscribed area; <1 cm in diameter | Wart (verruca), elevated moles, lichen planus |  |  Lichen planusb |

| PATCH | |||

| Flat, nonpalpable, irregularly shaped macule; >1 cm in diameter | Vitiligo, port-wine stains, mongolian spots, café-au-lait spots |  |  Vitiligob |

| PLAQUE | |||

| Elevated, firm, and rough lesion with flat top surface; >1 cm in diameter | Psoriasis, seborrheic and actinic keratoses |  |  Plaquea |

| WHEAL | |||

| Elevated irregularly shaped area of cutaneous edema; solid, transient; variable diameter | Insect bites, urticaria, allergic reaction |  |  Whealc |

| NODULE | |||

| Elevated, firm, circumscribed lesion; deeper in dermis than a papule; 1-2 cm in diameter | Erythema nodosum, lipomas |  |  Hypertrophic noduled |

| TUMOR | |||

| Elevated and solid lesion; may or may not be clearly demarcated; deeper in dermis; >2 cm in diameter | Neoplasms, benign tumor, lipoma, hemangioma |  |  Hemangiomab |

| VESICLE | |||

| Elevated, circumscribed, superficial, not into dermis; filled with serous fluid; <1 cm in diameter | Varicella (chickenpox), herpes zoster (shingles) |  |  Vesicles caused by varicellac |

| BULLA | |||

| Vesicle >1 cm in diameter | Blister, pemphigus vulgaris |  |  Blistere |

| PUSTULE | |||

| Elevated, superficial lesion; similar to a vesicle but filled with purulent fluid | Impetigo, acne |  |  Acneb |

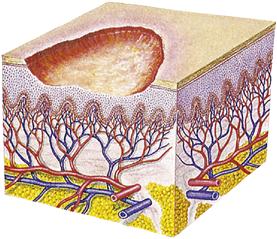

| CYST | |||

| Elevated, circumscribed, encapsulated lesion; in dermis or subcutaneous layer; filled with liquid or semisolid material | Sebaceous cyst, cystic acne |  |  Sebaceous cystb |

| TELANGIECTASIA | |||

| Fine, irregular red lines produced by capillary dilation | Telangiectasia in rosacea |  |  Telangiectasiad |

| SCALE | |||

| Heaped-up keratinized cells; flaky skin; irregular; thick or thin; dry or oily; variation in size | Flaking of skin with seborrheic dermatitis after scarlet fever, or flaking of skin following a drug reaction; dry skin |  |  Fine scalingf |

| LICHENIFICATION | |||

| Rough, thickened epidermis secondary to persistent rubbing, itching, or skin irritation; often involves flexor surface of extremity | Chronic dermatitis |  |  Stasis dermatitis in an early stageg |

| KELOID | |||

| Irregularly shaped, elevated, progressively enlarging scar; grows beyond the boundaries of the wound; caused by excessive collagen formation during healing | Keloid formation after surgery |  |  Keloidb |

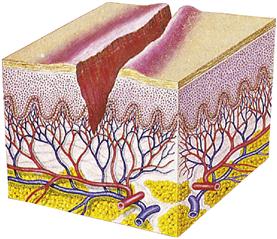

| SCAR | |||

| Thin to thick fibrous tissue that replaces normal skin after injury or laceration to the dermis | Healed wound or surgical incision |  |  Hypertrophic scard |

| EXCORIATION | |||

| Loss of the epidermis; linear hollowed-out crusted area | Abrasion or scratch, scabies |  |  Scabiesb |

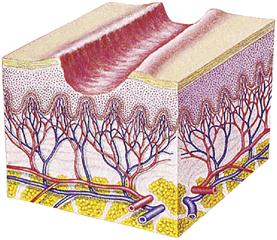

| FISSURE | |||

| Linear crack or break from the epidermis to the dermis; may be moist or dry | Athlete’s foot, cracks at the corner of the mouth |  |  Fissuresd |

| EROSION | |||

| Loss of part of the epidermis; depressed, moist, glistening; follows rupture of a vesicle or bulla | Varicella, variola after rupture |  |  Erosionh |

| ULCER | |||

| Loss of epidermis and dermis; concave; varies in size | Pressure sores, stasis ulcers |  |  Stasis ulcera |

| CRUST | |||

| Dried serum, blood, or purulent exudate; slightly elevated; size varies; brown, red, black or tan | Scab on abrasion, eczema |  |  Scabg |

| ATROPHY | |||

| Thinning of skin surface and loss of skin markings; skin translucent and paperlike | Striae; aged skin |  |  Aged sking |

Modified from Thompson, J., & Wilson, S. (1995). Health assessment for nursing practice. St. Louis: Mosby.

Assessment also includes the presence of rashes, scars, lesions, or ecchymoses and the distribution of hair. Assess temperature and texture by touch, using the palms of the hands to compare opposite body areas. For example, feel both legs before concluding that the left leg is cold. Use a cotton-tipped applicator to touch the sole of the foot and assess sensation. Inspect the nails for normal development, color, shape, and thickness. Clubbing (broadening) of the fingertips indicates decreased oxygen (hypoxemia) and should be reported. Inspect the hair for thickness, dryness, or dullness. Assessment also includes inspecting the mucous membranes for pallor or cyanosis. Document profuse sweating or any sign of impaired skin integrity. Examine the ceruminous and sebaceous glands for overactivity or underactivity using appropriate questions, such as, “Tell me how often the physician has had to remove the wax from your ears.”

Assessment of dark skin

The color of a person’s skin, and how dark or light it is, is genetically determined. Dark skin color results from the reflection of light as it strikes the underlying skin pigment. Melanocytes have increased activity and produce large amounts of melanin, which accounts for the darker skin color. This increased melanin forms a natural sun shield, accounting for the lower incidence of skin cancer in people with dark skin.

The structures of dark skin are no different from those of lighter skin, but they are more difficult to assess. Practice and comparison are necessary. Assessment is easier in areas where the epidermis is thin, such as the lips and mucous membranes. Rashes are often difficult to observe and may need to be palpated.

Dark skin is predisposed to certain skin conditions, including pseudofolliculitis, keloids, and mongolian spots. For some persons with dark skin, color cannot be used as an indicator of systemic conditions (e.g., flushed skin with fever) (see Cultural Considerations box).

-BR

-BR D-m

D-m

,

,  S-k

S-k r,

r,  KS-

KS- -d

-d t,

t,  -loydz,

-loydz,  K-

K- lz,

lz,  -v

-v ,

,  P-

P- lz,

lz,  -R-k

-R-k ,

,  S-

S- -kl,

-kl,  lz,

lz,