Case 4 | Aortic Incompetence (Lone)

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 8% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record

The pulse is regular* (give rate), of large volume and collapsing in character. The venous pressure is not raised but vigorous arterial pulsations can be seen in the neck (Corrigan’s sign†). The apex beat is thrusting (volume overload) in the anterior axillary line, in the sixth intercostal space. There is a high-pitched early diastolic murmur audible down the left sternal edge and in the aortic area; it is louder in expiration with the patient sitting forward. (The blood pressure may be wide with a high systolic and low diastolic. In severe cases it may be 250–300/30–50.)

The diagnosis is aortic incompetence. Now consider looking for Argyll Robertson pupils, high-arched palate or marfanoid appearance, or obvious features of an arthropathy especially ankylosing spondylitis. If these are not present the aortic incompetence is likely to be rheumatic in origin – rheumatic fever and infective endocarditis are the most common identifiable causes, although hypertension-induced aortic root dilation with secondary aortic incompetence is increasingly common.

The early diastolic murmur can be difficult to hear and is easily overlooked (see Vol. 2, Section F, Anecdote 276). It should be specifically sought with the patient sitting forward in expiration. Listen for the ‘absence of silence’ in the early part of diastole. The murmur is usually best heard over the mid-sternal region or at the lower left sternal edge. In some cases, particularly syphilitic aortitis, it is loudest in the aortic area. There is often an accompanying systolic murmur due to increased flow which does not necessarily indicate coexistent aortic stenosis (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 6).

If there is a mid-diastolic murmur at the apex, it may be an Austin Flint murmur‡ or it may represent some associated mitral valve disease. These two may be clinically indistinguishable, though the presence of a loud first heart sound and an opening snap suggest the latter. Though the first heart sound in the Austin Flint may be loud, it is never palpable (i.e. no tapping impulse).

Causes of Aortic Incompetence

Indications for Surgery

Although patients tolerate aortic incompetence longer than aortic stenosis (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 5), the clinician’s aim is to replace the valve before serious left ventricular dysfunction occurs. Every effort should be made to recognize any reduction in left ventricular function or reserve as early as possible (i.e. before symptoms appear). Serial echocardiograms will show a gradual increase in left ventricular dimensions.* Vasodilators, particularly ACE inhibitors and calcium antagonists, are thought to reduce the rate of deterioration in mild to moderate aortic incompetence, and should be considered even in asymptomatic patients. The left ventricular ejection fraction, though normal at rest, may show a subnormal rise during exercise. Aortic valve replacement may have to be undertaken as a matter of urgency in patients with infective endocarditis in whom the leaking valve causes rapidly progressive left ventricular dilation.

Case 5 | Aortic Stenosis (Lone)

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 7% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record 1

The pulse is regular (give rate), of small volume and slow rising. The venous pressure is not raised (unless there is cardiac failure). The apex beat is palpable 1 cm to the left of the mid-clavicular line in the fifth intercostal space (the apex position is normal or only slightly displaced in pure aortic stenosis unless the left ventricle is starting to fail) as a forceful sustained heave (pressure overload).* There is a systolic thrill palpable over the aortic area and the carotids (may be felt over the apex). Auscultation reveals a harsh ejection systolic murmur in the aortic area radiating into the neck, and the aortic second sound is soft (or absent). (An associated ejection click is usually present if the valve is bicuspid.) (The blood pressure is usually low normal with a decreased difference between systole and diastole – pulse pressure.)

The diagnosis is aortic stenosis.

Possible Causes

In the late stages of aortic stenosis when cardiac failure with low cardiac output supervenes, the murmur may become markedly diminished in intensity. The murmur of associated mitral stenosis should be carefully sought, particularly in the female patient, because the association of these two obstructive lesions tends to diminish the physical findings of each. Mitral stenosis is easily missed and the severity of aortic stenosis underestimated. As with all valvular heart diseases, echocardiography is of great value in a situation like this.

Indications for Surgery

In the adult patient valve replacement is indicated for symptoms if left ventricular function is preserved. Asymptomatic patients should be investigated further with carefully supervised exercise testing to determine true ‘asymptomatic’ status. In patients with poor left ventricular function, decision making is difficult. Functional imaging, such as dobutamine stress echocardiography, can be helpful in assessment of left ventricular reserve. Critical coronary lesions which can exacerbate the symptoms of aortic stenosis (and vice versa) should be managed at the same time. Asymptomatic children and young adults can be treated with valvotomy if the obstruction is severe, as the operative risk appears to be less than the risk of sudden death. This is only temporary but may postpone the need for valve replacement for many years. Valve repair is increasingly advocated, particularly in younger patients. Recent advances include percutaneous transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) currently indicated in patients unsuitable for standard aortic surgery.

β-Blockers, to slow the heart rate and hence increase ejection time, can be used in symptomatic patients pending surgery or in those unfit for surgery. β-Blockers also reduce cardiac work by reducing the rate of rise of systolic pressure and thus the effective valve gradient.

Calcific aortic stenosis is increasingly common and, due to the proximity of the atrioventricular node (and its subsequent involvement in the calcific process), may be associated with atrioventricular nodal block, particularly in the postsurgical population. Look for the small scar(s) of pacemaker implantation inferior to either clavicle.

Record 2

The carotid pulses are normal, the apical impulse is just palpable and not displaced. There are no thrills. There is an ejection systolic murmur which is not (usually) harsh or loud and is audible in the aortic area but only faintly in the neck. The aortic component of the second sound is well heard. The blood pressure is normal (or may be hypertensive – there may be a resultant ejection click).

These findings suggest aortic sclerosis* (or minimal aortic stenosis) rather than significant aortic stenosis. (NB: The differentiation of this from the other causes of a short systolic murmur is: prolapsing mitral valve, see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 10; trivial mitral incompetence and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 20.)

Case 6 | Mixed Aortic Valve Disease

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 5% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record 1

The pulse is regular (give rate) and slow rising (may have a bisferiens character). The venous pressure is not raised. The apex beat is palpable 1 cm to the left of the mid-clavicular line as a forceful, sustained heave (pressure loaded). There is a systolic thrill palpable at the apex, in the aortic area and also in the carotid. There is a harsh ejection systolic murmur in the aortic area radiating into the neck, the aortic component of the second sound is soft, and there is an early diastolic murmur down the left sternal edge audible when the patient is sitting forward in expiration.

The diagnosis is mixed aortic valve disease. Since the pulse is slow rising rather than collapsing, there is a systolic thrill, the second sound is soft and the apex has a forceful heaving quality, I think there is predominant aortic stenosis. (Systolic blood pressure will be low with a low pulse pressure.)

Record 2

The pulse is regular (give rate), of large volume and collapsing (may have a bisferiens character). The venous pressure is not raised. The apex beat is thrusting (volume loaded) in the anterior axillary line in the sixth intercostal space. There is a harsh ejection systolic murmur in the aortic area radiating into the neck and an early diastolic murmur down the left sternal edge (loudest with the patient sitting forward in expiration).

The diagnosis is mixed aortic valve disease. Since the pulse is collapsing rather than plateau in character and the apex is displaced and thrusting, I think the predominant lesion is aortic incompetence. (Blood pressure will show a wide pulse pressure.)

Often mixed aortic murmurs will be due to either aortic stenosis with incidental aortic incompetence or severe aortic incompetence with a systolic flow murmur.* In such cases commenting on dominance is easy. If it is not clear clinically which lesion is predominant and the examiners request your opinion, point out the factors in favour of each (see Table C3.2), stress that you would like to measure the blood pressure and how this would help and lean towards or, if possible, come down in favour of the one you think most likely, giving the reasons (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 3 for an example of how this might be done in the case of mixed mitral valve disease). Echocardiography will be very helpful but be aware that Doppler valve gradient is inaccurate in the presence of significant aortic incompetence; TOE may be helpful in more precisely delineating the anatomy of the aortic valve.

Table C3.2 Factors pointing to a predominant lesion in mixed aortic valve disease

| Aortic incompetence | Aortic stenosis | |

| Pulse | Mainly collapsing | Mainly slow rising |

| Apex | Thrusting, displaced (volume loaded) | Heaving, not displaced much (pressure loaded) |

| Systolic thrill | Absent | Present |

| Systolic murmur | Not loud, not harsh | Loud, harsh |

| Blood pressure: | ||

| systolic | High | Low |

| pulse pressure | Wide | Narrow |

Treatment

There is a trend towards aortic valve repair if at all possible, particularly in younger patients with congenital aortic valve disease.

As for any valve lesion, surgery is generally indicated for symptoms in stenotic lesions (pressure overload) and for signs of left ventricular compromise in regurgitant lesions (volume overload). Exercise testing is advocated in all but severe aortic stenosis to objectively assess exercise tolerance. Echocardiography is vital for follow-up for subtle signs of deteriorating function of the volume-loaded ventricle.

Case 7 | Mitral Stenosis (Lone)

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 5% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record

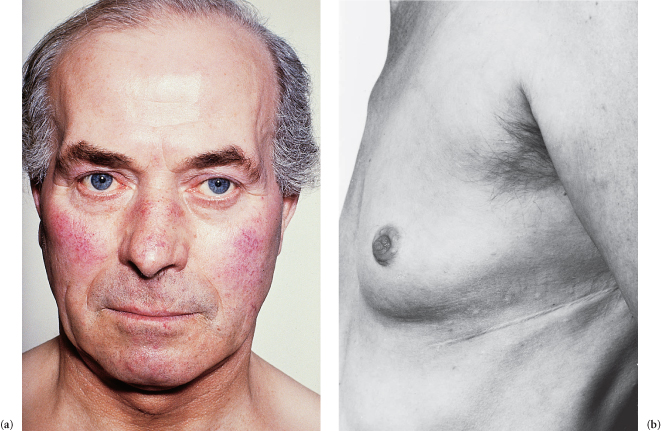

There is a malar flush and a left thoracotomy scar. The pulse is irregularly irregular (give rate) in rate and volume (if sinus rhythm, the volume is usually small). The venous pressure is not raised, and there is no ankle or sacral oedema (unless in cardiac failure). The cardiac impulse is tapping (palpable first heart sound) and the apex is not displaced. There is a left parasternal heave. The first heart sound is loud, there is a loud pulmonary second sound and an opening snap followed by a mid-diastolic rumbling murmur (with presystolic accentuation if the patient is in sinus rhythm) localized to the apex and heard most loudly with the patient in the left lateral position.*

The diagnosis is mitral stenosis. The patient has had a valvotomy in the past. There are signs of pulmonary hypertension.

Other Signs Which May be Present

The opening snap soon after the second sound‡ in tight mitral stenosis (<0.09 sec – mean left atrial pressure above 20 mmHg); longer after the second sound in mild mitral stenosis (>0.1 sec – mean left atrial pressure below 15 mmHg); absent if the mitral valve is calcified (first heart sound soft).

Indications for Intervention (Surgery or Percutaneous Transcatheter Valvuloplasty)

Criteria for Valvotomy (Open or Transcatheter)¶

Figure C3.1 (a) Mitral facies. (b) Thoracotomy scar for mitral valvotomy.

Case 8 | Irregular Pulse

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 5% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Survey Note:

though an irregular pulse was usually encountered in the examination as a feature in the common valvular short cases, occasionally it was itself the main focus of a short case. This was often because the patient had a goitre.

Record

The pulse is … /min and irregularly irregular in rate and volume, suggesting atrial fibrillation with a controlled* ventricular response (uncontrolled if the rate is >90/min). Now look at the neck (goitre), eyes (exophthalmos), face (mitral facies, hypothyroidism† or hemiplegia due to an embolus) and chest (thoracotomy scar).‡

Differential Diagnosis

The differentiation of an irregular pulse due to controlled atrial fibrillation from that of multiple extrasystoles will depend upon the observation that only in atrial fibrillation do long pauses occur in groups of two or more (with ectopic beats, the compensatory pause follows a short pause because the ectopic is premature). Furthermore, exercise may abolish extrasystoles but worsen the irregularity of atrial fibrillation. Without recourse to an electrocardiogram, atrial fibrillation can be difficult to distinguish from atrial flutter with variable block, from multiple atrial ectopics due to a shifting pacemaker, and sometimes from paroxysmal atrial tachycardia with block. Only in atrial fibrillation is the ventricular rhythm truly chaotic.

Causes of Atrial Fibrillation

Treatment

Oral anticoagulants and atrial fibrillation: the advice relating to this topic is changing rapidly. It is, however, a perfect subject for PACES so make sure you are up to date!* Likewise, the best management of atrial fibrillation. If asked, choose a scenario to discuss, e.g. acute-onset atrial fibrillation in an elderly person associated with a chest infection or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in an otherwise fit 40-year-old, etc. Do not forget the role of cardioversion, and remember that management depends on the treatment aim, i.e. restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm or control of the resulting irregular ventricular rate.

Case 9 | Other Combinations of Mitral and Aortic Valve Disease

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 4% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Survey Note:

patients with any combination of aortic and mitral valve disease may be found in the examination (including, very rarely, lesions of one valve in combination with a prosthetic valve; see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 1). Whenever you are examining the heart it is essential that, having found some obvious murmurs, you go in search of the others which may be present and less obvious, before presenting your findings (see Vol. 2, Section F, Experience 185 and Anecdote 276).

If the examiner seeks an opinion as to which are the main lesions, or if you feel confident to offer one, the criteria used are the same as those described under mixed mitral valve disease (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 3) and mixed aortic valve disease (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 6). The example here is of a record of mixed mitral and aortic valve disease.

Record

There is a left thoracotomy scar and the patient has a malar flush. The pulse is irregularly irregular (give rate) and slow rising (can be difficult to assess if the patient is in atrial fibrillation) in character. The venous pressure is not elevated. The apex is … (give appropriate word on the basis of what you find, e.g. thrusting, heaving, lifting, etc.) in the anterior axillary line and there is a left parasternal heave. There is a systolic thrill at the apex, in the aortic area and in the neck. The first heart sound is loud, there is a harsh ejection systolic murmur in the aortic area radiating into the neck, a pansystolic murmur at the lower left sternal edge radiating to the apex and to the axilla, an early diastolic murmur just audible in the aortic area and down the left sternal edge with the patient sitting forward in expiration, and an opening snap followed by a mid-diastolic rumbling murmur localized to the apex.

The findings suggest mixed aortic and mitral valve disease. The slow rising pulse suggests that aortic stenosis is the dominant aortic valve lesion. It is not possible to ascertain clinically which is the major mitral valve lesion.* Further investigation involving transthoracic echocardiography, probably leading on to transoesophageal echo and/or cardiac catheterization with left ventricular angiography, would be required to assess the haemodynamic significance of each lesion.

Case 10 | Mitral Valve Prolapse

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record

The pulse (in this well-looking patient) is regular (give rate) and the venous pressure is not raised. The apex beat is palpable in the fifth intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line. There are no heaves or thrills. On auscultation, the heart sounds are normal but there is a mid-systolic click * (which is usually but not always) followed by a late systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur loudest at the left sternal edge (as the condition progresses the murmur develops the characteristics of mitral incompetence; see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 2).

These findings suggest mitral valve prolapse (floppy posterior mitral valve leaflet – echocardiography is useful for confirmation).

The prolapse is increased by anything which decreases cardiac volume (standing position, Valsalva manoeuvre) and as a result the click and murmur occur earlier during systole and the murmur is prolonged. Increasing cardiac volume (squatting position, propranolol) has the reverse effect. Phonocardiography documents these effects well. Mitral valve prolapse (said to occur in 5–10% of the population,† more commonly in females) is usually asymptomatic but may be associated with atypical chest pain, palpitation, fatigue and dyspnoea. The symptoms may become worse once the patient knows there is a murmur. The prognosis is good† but complications can include infective endocarditis, atrial and ventricular dysrhythmias, worsening mitral incompetence, embolic phenomena (transient ischaemic attacks, amaurosis fugax, acute hemiplegia), rupture of the mitral valve (age-related degenerative changes) and sudden death. The condition may be familial and there may be a family history of sudden death. There is a serious risk of precipitating cardiac neurosis which may, at least in part, contribute to the association with atypical chest pain. There is often myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve, deposition of acid mucopolysaccharide material and redundant valve tissue.

Causes and Associations

Other Points of Note

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) can be an incidental finding during echocardiography.

Indications for surgery are as for mitral regurgitation (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 2); surgical repair rather than valve replacement is favoured.

Palpitations are usually due to benign ventricular ectopy and generally respond well to β-blockade if symptoms are troublesome.

Other causes of a short systolic murmur audible at the apex should always be thought of and excluded. These are:

Trivial mitral incompetence (the usual cause – the murmur may not be pansystolic but there is no click)

Aortic stenosis/sclerosis (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 5)

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 20).

Case 11 | Tricuspid Incompetence

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 3% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record

The JVP is elevated (say height*) and shows giant v waves † which oscillate the earlobe (if the venous pressure is high enough) and which are diagnostic of tricuspid incompetence. (Now, if allowed, examine the heart, respiratory system and abdomen.‡)

The most common cause of tricuspid incompetence is not organic but dilation of the right ventricle and of the tricuspid valve ring due to right ventricular failure§ in conditions such as:

Causes of Primary Tricuspid Incompetence

Case 12 | Ventricular Septal Defect

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 2% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Survey Note:

youthfulness of patient is sometimes a clue to the diagnosis.

Record

The pulse is regular (give rate) and the venous pressure is not raised. The apex beat is (may be) palpable halfway between the mid-clavicular line and the anterior axillary line, and there is a left parasternal heave (there may be a systolic thrill). There is a pansystolic murmur at the lower left sternal edge which is also audible at the apex. (The pulmonary second sound may be loud due to pulmonary hypertension and there may be an early diastolic murmur of secondary pulmonary incompetence.)*

The diagnosis is ventricular septal defect.

Other Features of Ventricular Septal Defect

Case 13 | Marfan’s Syndrome

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 1% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Survey Note:

see Vol. 2, Section F, Experience 26.

Marfan’s syndrome is dealt with in Vol. 3, Station 5, Locomotor, Case 9.

Case 14 | Pulmonary Stenosis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 1% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record

The pulse is regular and the JVP is not elevated (prominent a wave in severe cases).* The cardiac apex is not palpable but there is (may be) a left parasternal heave. A systolic thrill is palpable over the left second and third interspaces. An ejection click and a systolic murmur (and may be also a fourth heart sound) are heard over the pulmonary area. The murmur is louder during inspiration and radiates to the suprasternal notch. The second sound is (may be) split (the pulmonary component is soft).†

The diagnosis is pulmonary stenosis.

Poststenotic dilation of the pulmonary arteries may be seen on the chest X-ray and, in the severe case, right ventricular hypertrophy and diminution of pulmonary vascular markings. A minor degree of pulmonary stenosis is compatible with a normal life span. Surgical relief is required in symptomatic cases or if there is a gradient of more than 50 mmHg across the pulmonary valve. Balloon valvotomy is becoming the technique of choice in children and young adults, especially if the valve is not dysplastic. If treatment is delayed too long in severe pulmonary stenosis, an irreversible fibrotic change can take place in the hypertrophied right ventricle.

Pulmonary stenosis may occur in the setting of surgically corrected tetralogy of Fallot. In this case there will usually be a left or right thoracotomy scar associated with a previous Blalock shunt (see Station 3, Cardiovascular, Case 23) and a midline scar from the later complete Fallot repair. The dysplastic pulmonary valve was often replaced with a valved conduit which can calcify and obstruct in later life. If there is a single mid-line scar, the patient may have had an open pulmonary valvotomy in childhood, which often leaves a loudish murmur without any objective evidence of obstruction. Echocardiography is the key investigation.

Case 15 | Ankylosing Spondylitis

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 0.8% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Survey Note:

see Vol. 2, Section F, Anecdote 102.

Ankylosing spondylitis is dealt with in Vol. 3, Station 5, Locomotor, Case 6.

Case 16 | Atrial Septal Defect

Frequency in Survey:

main focus of a short case or additional feature in 0.8% of attempts at PACES Station 3, Cardiovascular.

Record 1

The pulse in this middle-aged female is irregularly irregular (onset of atrial fibrillation is usually the cause of symptoms after the third or fourth decade, otherwise asymptomatic). The JVP is not elevated (unless in right heart failure). The apex beat is just palpable and not displaced. The second heart sound is widely split and the two-component split is not influenced by respiration (fixed splitting). There is an ejection systolic murmur (due to increased flow across the pulmonary valve) over the pulmonary area. (Occasionally there may be an ejection click due to pulmonary artery dilation.)

The diagnosis is atrial septal defect of little haemodynamic significance.

Record 2

The pulse is irregularly irregular (atrial fibrillation) in this middle-aged woman. There is no oedema and the JVP is not elevated. The apex beat is just palpable in the left fifth intercostal space just outside the mid-clavicular line, there is a left parasternal heave (right ventricular volume overload), and there is (may be) a systolic thrill over the pulmonary area (large left-to-right shunt). The second sound is widely split. There is an ejection systolic murmur, and an ejection click (may be palpable) over the pulmonary area, and a mid-diastolic rumble over the tricuspid area (a large left-to-right shunt causes increased flow through the tricuspid valve).

The diagnosis is a haemodynamically significant atrial septal defect.

Male-to-female ratio is 1/3.

Other Features of Atrial Septal Defect

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree