Uncertainty in illness theory

Donald E. Bailey Jr. and Janet L. Stewart

“My theory can be applied to both practice and research. It has been used to explain clinical situations and design interventions that lead to evidence-based practice. Current and future nurse scientists have and will continue to extend the theory to different patient populations. This work has the potential to transform health care.

(Mishel, personal communication, May 28, 2008)”

Merle H. Mishel

1939 to present

Credentials and background of the theorist

Merle H. Mishel was born in Boston, Massachusetts. She graduated from Boston University with a B.A. in 1961 and received her M.S. in psychiatric nursing from the University of California in 1966. Mishel completed her M.A. and Ph.D. in social psychology at the Claremont Graduate School in Claremont, California, in 1976 and 1980, respectively. Her dissertation research was supported by a National Research Service Award to develop and test the Perceived Ambiguity in Illness Scale, later named the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS-A). The original scale has been used as the basis for the following three additional scales:

Photo Credit: Dr. Michael Belyea, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

The authors wish to think Dr. Merle Mishel for her review and input for this chapter.

Early in her professional career, Mishel practiced as a psychiatric nurse in acute care and community settings. While pursuing her doctorate, she was on faculty in the Department of Nursing at the California State University at Los Angeles, rising from assistant professor to full professor. She practiced as a nurse therapist in community and private practice settings from 1973 to 1979. After completing her doctorate in social psychology, Mishel became associate professor at the University of Arizona College of Nursing in 1981 and full professor in 1988. She was Division Head of Mental Health Nursing from 1984 to 1991. While at Arizona, Mishel received numerous intramural and extramural research grants that supported the continued development of the theoretical framework of uncertainty in illness. During this period, she continued practicing as a nurse therapist with the heart transplant program at the University Medical Center. She was inducted as a fellow in the American Academy of Nursing in 1990.

Mishel moved back east in 1991 and joined the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing as professor, and she was awarded the endowed Kenan Professor of Nursing Chair in 1994. Friends of the National Institute of Nursing Research presented her with a Research Merit Award in 1997 and invited her to present her research as an exemplar of federally funded nursing intervention studies at a Congressional Breakfast in 1999. She is Director of the T-32 Institutional National Research Service Award Training Grant, Interventions for Preventing and Managing Chronic Illness that awards predoctoral and postdoctoral fellowships to nurses who are interested in developing interventions for underserved chronically ill patients. Mishel’s research program is noteworthy for being funded continually by the National Institutes of Health from 1984 through 2011. Each research grant has built upon findings from prior studies to move systematically toward theoretically derived scientifically tested nursing interventions. Currently Mishel is co-leader of the Hillman Scholars Program designed to produce a new generation of nurse innovators with knowledge and research skills to solve complex health problems and improve patient care.

Among her many awards, Mishel received a Sigma Theta Tau International Sigma Xi Chapter Nurse Research Predoctoral Fellowship from 1977 to 1979 and received the Mary Opal Wolanin Research Award in 1986. In 1987, Mishel was first alternate for a Fulbright Award. She has been a visiting scholar at many institutions throughout North America, including University of Nebraska, University of Texas at Houston, University of Tennessee at Knoxville, University of South Carolina, University of Rochester, Yale University, and McGill University. Mishel was doctoral program consultant for the University of Cincinnati College of Nursing from 1991 to 1992 and Rutgers University School of Nursing in 1993. In 2004, she received the Linnea Henderson Research Fellowship Program Award from the Kent State University School of Nursing. Over the last 20 years, she has presented more than 80 invited addresses at schools of nursing throughout the United States and Canada. With growing international interest in her theory and measurement models, Mishel conducted an International Symposium on Uncertainty at Kyungpook National University in Daegu, South Korea, was a visiting scholar at Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand, and delivered the keynote address for the Japanese Society of Nursing Research annual convention, in Sapporo, Japan.

Mishel is a member of many professional organizations, including the American Academy of Nursing, Sigma Theta Tau International, the American Psychological Association, the American Nurses Association, the Society of Behavioral Medicine, the Oncology Nursing Society, the Southern Nursing Research Society, and the Society for Education and Research in Psychiatric Nursing. She served as a grant reviewer for the National Cancer Institute, the National Center for Nursing Research, and the National Institute on Aging, and she was a charter member of the study section on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Theoretical sources

When Mishel began her research into uncertainty, the concept had not been applied in the health and illness context. Her original Uncertainty in Illness Theory (Mishel, 1988) drew from existing information-processing models (Warburton, 1979) and personality research (Budner, 1962) from psychology that characterized uncertainty as a cognitive state resulting from insufficient cues with which to form a cognitive schema or internal representation of a situation or event. Mishel attributes the underlying stress-appraisal-coping-adaptation framework in the original theory to the work of Lazarus and Folkman (1984). The unique aspect of this framework was its application to uncertainty as a stressor in the context of illness, a particularly meaningful proposal for nursing.

With the reconceptualization of the theory, Mishel (1990) recognized that the Western approach to science supported a mechanistic view with emphasis on control and predictability. She used critical social theory to recognize bias inherent in the original theory, an orientation toward certainty and adaptation. Mishel incorporated tenets from chaos theory and open systems for a more accurate representation of how chronic illness creates disequilibrium and how people incorporate continual uncertainty to find new meaning in illness.

Use of empirical evidence

The Uncertainty in Illness Theory grew out of Mishel’s dissertation research with hospitalized patients, using both qualitative and quantitative findings to generate the first conceptualization of uncertainty in the context of illness. With the publication of Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Scale (Mishel, 1981), extensive research began into adults’ experiences with uncertainty related to chronic and life-threatening illnesses. Considerable empirical evidence has accumulated to support Mishel’s theoretical model in adults. Several integrative reviews of uncertainty research have comprehensively summarized and critiqued the state of the science (Cahill, Lobiondo-Wood, Bergstrom, et al., 2012; Hansen, Rørtveit, Leiknes, et al., 2012; Mishel, 1997a, 1999; Stewart & Mishel, 2000). The authors included studies that directly support the elements of Mishel’s uncertainty model.

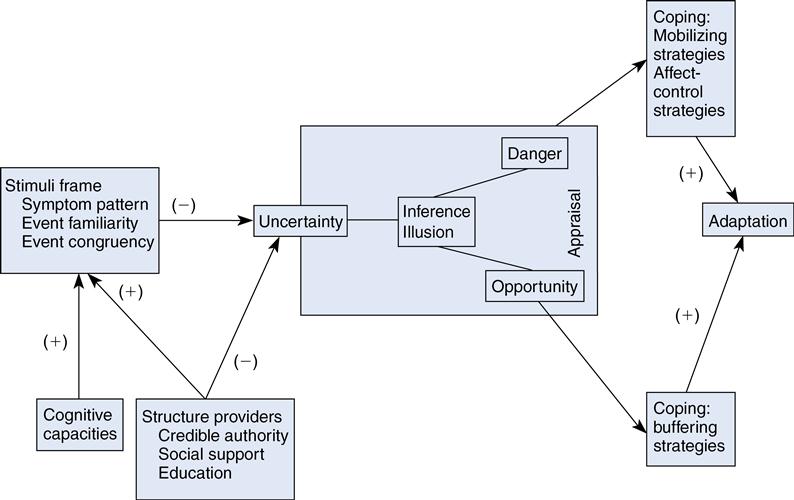

Most empirical studies have been focused on two antecedents of uncertainty, stimuli frame and structure providers, and the relationship between uncertainty and psychological outcomes. Mishel tested other elements of the model, such as the mediating roles of appraisal and coping, early in her program of research (Mishel & Braden, 1987; Mishel, Padilla, Grant, et al., 1991; Mishel & Sorenson, 1991), and these elements, as well as cognitive capacity as an antecedent to uncertainty, generated less research attention.

Several studies have shown that objective or subjective indicators of the severity of life-threat or illness symptoms associate positively with uncertainty (Baird & Eliasziw, 2011; Grootenhuis & Last, 1997; Somjaivong, Thanasilp, Preechawong, et al., 2011). Across a sustained illness trajectory, unpredictability in symptom onset, duration, and intensity has been related to perceived uncertainty (Arroll, Dancey, Attree, et al., 2012; Becker, Jason-Bjerklie, Benner, et al., 1993; Kim, Lee, & Lee, 2012; Murray, 1993). Similarly, the ambiguous nature of illness symptoms and the consequent difficulty in determining the significance of physical sensations have been identified as sources of uncertainty (Cohen, 1993; Hilton, 1988; Nelson, 1996).

Social support has been shown to have a direct impact on uncertainty by reducing perceived complexity and an indirect impact through its effect on the predictability of symptom pattern (Lin, 2012; Mishel & Braden, 1988; Somjaivong, Thanasilp, Preechawong, et al., 2011; Scott, Martin, Stone, et al., 2011). The perception of stigma associated with some conditions, particularly HIV infection (Regan-Kubinski & Sharts-Hopko, 1995) and Down’s syndrome (Van Riper & Selder, 1989), served to create uncertainty when families were unsure about how others would respond to the diagnosis. Family members have been shown to experience high levels of uncertainty as well, which may further reduce the amount of support experienced by the patient (Baird & Eliasziw, 2011; Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Hilton, 1996; Wineman, O’Brien, Nealon, et al., 1993). Uncertainty was heightened by interactions with health care providers when patients and family members received unclear information, received simplistic explanations that did not fit their experience, or perceived that care providers were not expert or responsive enough to help them manage the intricacies of the illness (Becker, Jason-Bjerklie, Benner, et al., 1993; Checton & Greene, 2012; Sharkey, 1995; Step & Ray, 2011).

Numerous studies have reported the negative impact of uncertainty on psychological outcomes, characterized variously as anxiety, depression, hopelessness, psychological distress (Arroll, Dancey, Attree, et al., 2012; Failla, Kuper, Nick, et al., 1996; Grootenhuis & Last, 1997; Kim & So, 2012; Miles, Funk, & Kasper, 1992; Mishel & Sorenson, 1991; Page, Fedele, Pai, et al., 2012; Schepp, 1991; Wineman, 1990), quality of life (Lasker, Sogolow, Short, et al., 2011; Somjaivong Thanasilp, Preechawong, et al., 2011; Song, Northouse, Braun, et al., 2011), satisfaction with family relationships (Wineman, O’Brien, Nealon, et al., 1993), satisfaction with health care services (Green & Murton, 1996; Tai-Seale, Stults, Zhang, et al., 2012), and family caregivers’ maintenance of their own self-care activities (Brett & Davies, 1988; O’Brien, Wineman, & Nealon, 1995).

In 1990, the original theory was expanded to include the idea that uncertainty may not be resolved but may become part of an individual’s reality. In this context, uncertainty is appraised as an opportunity that prompts the formation of a new, probabilistic view of life. To adopt this new view of life, the patient must be able to rely on social resources and health care providers who themselves accept the idea of probabilistic thinking (Mishel, 1990). When uncertainty is framed as a normal part of life, it becomes a positive force for multiple opportunities and resulting positive mood states (Gelatt, 1989; Mishel, 1990).

Support for the reconceptualized Uncertainty in Illness Theory has been found in predominantly qualitative studies of people with chronic and life-threatening illnesses. The process of formulating a new view of life is described by women with breast cancer and cardiac disease as a revised life perspective (Hilton, 1988), new life goals (Carter, 1993), new ways of being in the world (Mast, 1998; Nelson, 1996), growth through uncertainty (Pelusi, 1997), and new levels of self-organization (Fleury, Kimbrell, & Kruszewski, 1995). In studies of men with chronic illness or their caregivers, the process is described as transformed self-identity and new goals for living (Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991), a more positive perspective on life (Katz, 1996), reevaluating what is worthwhile (Nyhlin, 1990), contemplation and self-appraisal (Charmaz, 1995), uncertainty viewed as opportunity (Baier, 1995), and redefining normal and building new dreams (Mishel & Murdaugh, 1987).

Major assumptions

Person

Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory is middle-range and focused on persons. Mishel’s original Uncertainty in Illness Theory, first published in 1988, included several major assumptions (Figure 28–1). The first two reflect how uncertainty was conceptualized within psychology’s information-processing models, as follows:

Two more assumptions reflect the uncertainty theory’s roots in traditional stress and coping models that posit a linear stress → coping → adaptation relationship as follows:

Mishel challenged assumptions 3 and 4 in her reconceptualization of the theory, published in 1990. The reconceptualization came about as a result of contradictory findings when the theory was applied to people with chronic illnesses. The original formulation of the theory held that uncertainty typically is appraised as an opportunity only in conditions that represent a known downward trajectory; in other words, uncertainty is appraised as opportunity when it is the alternative to negative certainty. Mishel and others found that people also appraised uncertainty as an opportunity in situations without a certain downward trajectory, particularly in long-term chronic illnesses, and that in this context people often developed a new view of life.

It was at this time that Mishel turned to chaos theory to explain how prolonged uncertainty could function as a catalyst to change a person’s perspective on life and illness. Chaos theory contributed two of the following theoretical assumptions that replace the linear stress A coping A adaptation outcome portion of the model as follows:

• People, as biopsychosocial systems, typically function in far-from-equilibrium states.

• Major fluctuations in a far-from-equilibrium system enhance the system’s receptivity to change.

• Fluctuations result in repatterning, which is repeated at each level of the system.

In Mishel’s reconceptualized theory, neither the antecedents to uncertainty nor the process of cognitive appraisal of uncertainty as danger or opportunity change. However, uncertainty over time, associated with a serious illness, functions as a catalyst for fluctuation in the system by threatening one’s preexisting cognitive model of life as predictable and controllable. Because uncertainty pervades nearly every aspect of a person’s life, its effects become concentrated and ultimately challenge the stability of the system. In response to the confusion and disorganization created by continued uncertainty, the system ultimately must change in order to survive.

Ideally, under conditions of chronic uncertainty, a person gradually moves away from an evaluation of uncertainty as aversive to adopt a new view of life that accepts uncertainty as a part of reality (Figure 28–2). Thus uncertainty, especially in chronic or life-threatening illness, can result in a new level of organization and a new perspective on life, incorporating the growth and change that result from uncertain experiences.

Theoretical assertions

Mishel asserted the following (1988, 1990):

Logical form

As a middle-range theory derived from and applicable to clinical practice, Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Theory is an exemplar of the multiple steps required to develop theory with both heuristic and practical value. Neither purely inductive nor deductive, Mishel’s theoretical work initially arose from questioning the nature of an important clinical problem, followed by systematic qualitative and quantitative inquiry and careful application of theory borrowed from other disciplines. Since publication of the original theory in 1988, Mishel and others have carried out numerous empirical tests of the relationships among the major constructs in the model, applying and largely confirming the theory in illness contexts. Mishel’s reconceptualization of the theory in 1990 was deductive in that it was developed from principles of chaos theory and was confirmed by empirical evidence from qualitative studies that suggested that people’s responses to uncertainty changed over time within the context of serious chronic illnesses. Thus Mishel’s theory represents the bidirectional process where theory informs and is informed by research.

Acceptance by the nursing community

Practice

Mishel’s theory describes a phenomenon experienced by acute and chronically ill individuals and their families. The theory has its beginning in Mishel’s own experience with her father’s battle with cancer. During his illness, he began to focus on events that seemed unimportant to those around him. When asked why he had chosen to focus on such events, he replied that when these activities were being done, he understood what was happening to him. Mishel believed this was her father’s way of taking control and making sense out of an overwhelming situation. She knew early in the development of her concept and theory that nurses could identify the phenomenon from their experiences in caring for patients.

Several nurses have moved the theory from research to practice. Hansen and colleagues (2012) synthesized findings from qualitative studies to yield a typology of patient experiences of uncertainty that guides nursing engagement and intervention. Similarly, the theory has been used in recommendations for the practice of critical, medical-surgical, and enterostomal nursing care (Hilton, 1992; Righter, 1995; Wurzbach, 1992).

Based on review of the database of the Managing Uncertainty in Illness Scale users (Mishel, 1997b), master’s-prepared clinicians seek to understand the experience of uncertainty in a variety of clinical settings and patient populations. The scale and theory are used by clinicians from 15 countries other than the United States.

Education

The theory has been widely used by graduate students as the theoretical framework for theses and dissertations, as the topic of concept analysis, and for the critique of middle-range nursing theory. Mishel uses the theory as an exemplar to illustrate how theory guides the development of nursing interventions in her doctoral-level courses. Mishel frequently presents school of nursing lectures, seminars, and symposia nationally and internationally, sharing her empirical findings and the process of theory development for faculty and students.

Research

As described above, a large body of knowledge has been generated by researchers using the Uncertainty in Illness Theory and scales. Mishel’s program of research encompassed testing the psychoeducational nursing interventions derived from the theoretical model in samples of adults with breast and prostate cancers. The scales and theory used by nurse researchers and scientists from other disciplines describe and explain psychological responses of people experiencing uncertainty due to illness and test interventions to manage uncertainty in illness contexts. The scales have been translated into 12 languages and applied in research throughout the world. Mishel (1997a, 1999) reviewed research conducted on uncertainty in acute and chronic illness and coauthored a review of the research on uncertainty in childhood illness (Stewart & Mishel, 2000). Current research on uncertainty in illness is focused on theory testing.

Further development

Mishel and colleagues have used the original theory as the framework for seven federally funded nursing intervention studies. The intervention has increased cancer knowledge, reduced symptom burden, and improved quality of life in Mexican-American, Caucasian, and African-American women with breast cancer, in African-American and Caucasian men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, and in those with localized, advanced, or recurrent prostate cancer and their family members (Gil, Mishel, Belyea, et al., 2004; Gil, Mishel, Belyea, et al., 2006; Gil, Mishel, Germino, et al., 2005; Mishel, Belyea, Germino, et al., 2002; Mishel, Germino, Belyea, et al., 2003; Mishel, Germino, Lin, et al., 2009). The applicability of the theory to the context of serious childhood illness has been supported in parents of children with HIV infection (Santacroce, Deatrick, & Ledlie, 2002) and in children undergoing treatment for cancer (Lin, Yeh, & Mishel, 2010; Stewart, 2003; Stewart, Lynn, & Mishel, 2010; Stewart, Mishel, Lynn, et al., 2010). Bailey uses the theory to support research in chronic hepatitis C, a new and often silent disease (Bailey, Barroso, Muir, et al., 2010; Bailey, Landerman, Barroso, et al., 2009), and she is testing an intervention in patients awaiting liver transplant and their caregivers.

From qualitative data supporting the reconceptualized theory, Mishel and Fleury (1994) developed the Growth Through Uncertainty Scale (GTUS) to measure the new view of life that can emerge from continual uncertainty. Researchers have also used the reconceptualized theory to understand the uncertainty experience of long-term survivors of breast cancer (Mast, 1998) and individuals with schizophrenia and their family members (Baier, 1995). The reconceptualized theory served as the foundation for Mishel and colleagues’ nursing intervention study of women younger than 50 years of age facing the enduring uncertainties inherent in surviving breast cancer. Bailey used the theory and data from qualitative interviews with older men who had elected watchful waiting as treatment for their prostate cancer, to develop a nursing intervention to integrate uncertainty into their lives, view their lives in a positive perspective, and improve their quality of life (Bailey, Wallace, & Mishel, 2007). In the first study of the Uncertainty Management Intervention for Watchful Waiting, men came to see their lives in a new and positive light, reported their quality of life as higher than did the control group, and expected it to be high in the future (Bailey, Mishel, Belyea, et al., 2004). Wallace (now, Kazer) and Bailey conducted a pilot test of a web-based version of the intervention for men with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance (previously referred to as watchful waiting) (Kazer, Bailey, Sanda, et al., 2011).

The substantial empirical evidence supporting the Uncertainty in Illness theories provides a strong foundation to extend the theory to intervention development and improve patient and family outcomes. In addition to Mishel’s own intervention studies in patients with breast and prostate cancer, several researchers tested interventions to help patients manage uncertainty. Many were directed at reducing sources of uncertainty (Chair, Chou, Sit, et al., 2012; Chiou & Chung, 2012; Faithfull, Cockle-Hearne, & Khoo, 2011; Kazer, Bailey, Sanda, et al., 2011; Muthusamy, Leuthner, Gaebler-Uhing, et al., 2012; Schover, Canada, Yuan, et al., 2012). Others focused on the provision of support (Heiney, Adams, Wells, et al., 2012) and specific coping strategies (Faithfull, Cockle-Hearne, & Khoo, 2011) to help patients manage their uncertainty.

Critique

Clarity

Uncertainty is the primary concept of this theory and is defined as a cognitive state in which individuals are unable to determine the meaning of illness-related events (Mishel, 1988). The original theory postulates that managing uncertainty is critical to adaptation during illness and explains how individuals cognitively process illness-associated events and construct meaning from them. The original theory’s concepts were organized in a linear model around the following three major themes:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree