The Child with a Gastrointestinal Condition

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Discuss three common gastrointestinal anomalies in infants.

3. Discuss the postoperative nursing care of an infant with pyloric stenosis.

4. Discuss the dietary management of celiac disease.

5. Understand the symptoms, treatment, and nursing care of a child with Hirschsprung’s disease.

6. Understand the treatment and nursing care of a child with intussusception.

7. Interpret the nursing management of an infant with gastroesophageal reflux.

8. Differentiate between three types of dehydration.

9. Explain why infants and young children become dehydrated more easily than adults.

10. Understand how nutritional deficiencies influence growth and development.

11. Review the prevention of the spread of thrush in infants and children.

12. Trace the route of the pinworm cycle and describe how reinfection takes place.

13. Prepare a teaching plan for the prevention of poisoning in children.

14. List two measures to reduce the effect of acetaminophen poisoning in children.

Key Terms

anasarca (ăn-ă-SĂHR-kă, p. 663)

anthelmintics (ănt-hĕl-MĬN-tĭkz, p. 667)

colitis (p. 655)

colonoscopy (p. 648)

currant jelly stools (p. 654)

encopresis (ĕn-kō-PRĒ-tĭs, p. 657)

endoscopy (p. 648)

enterocolitis (ĕn-tŭr-ō-kō-LĪ-tĭs, p. 653)

guarding (p. 666)

herniorrhaphy (hŭr-nē-ŎR-ă-fē, p. 665)

homeostasis (hō-mē-ō-STĀ-sĭs, p. 661)

hypertonic (hī-pŭr-TŎN-ĭk, p. 662)

hypotonic (hī-pō-TŎN-ĭk, p. 662)

incarcerated hernia (p. 654)

isotonic (ī-sō-TŎN-ĭk, p. 662)

McBurney’s point (p. 666)

parenteral fluids (pă-RĔN-tŭr-ăl, p. 660)

peritoneal dialysis (pĕ-rĭ-tŏ-NĒ-ăl dī-ĂL-ĭ-sĭs, p. 669)

pica (PĪ-kă, p. 670)

plumbism (p. 669)

polyhydramnios (pŏl-ē-hī-DRĂM-nē-ŏs, p. 649)

projectile vomiting (p. 650)

pruritus (prū-RĪ-tŭs, p. 648)

rebound tenderness (p. 666)

reflux (p. 656)

sigmoidoscopy (p. 648)

stenosis (p. 650)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

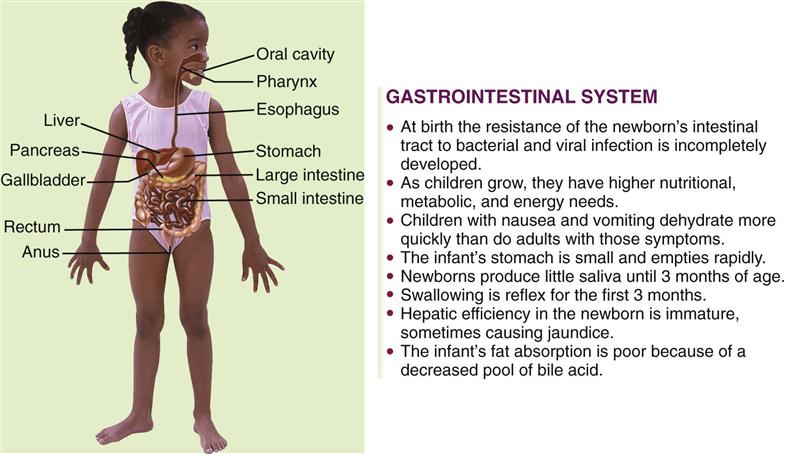

The Gastrointestinal Tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract transports and metabolizes nutrients necessary for the life of the cell. It extends from the mouth to the anus. Nutrients are broken down into absorbable products by enzymes from various digestive organs. The anatomy of the digestive tract, with some of the differences between that of the child and that of the adult, is depicted in Figure 28-1. The primitive digestive tube is formed by the yolk sac and is divided into the foregut, the midgut, and the hindgut. The foregut evolves into the pharynx, the lower respiratory tract, the esophagus, the stomach, the duodenum, and the beginning of the common bile duct. The midgut elongates in the fifth fetal week to form the primary intestinal loop. The remainder of the large colon is derived from the primitive hindgut. The liver, pancreas, and biliary tree evolve from the foregut. The anal membrane ruptures at 8 weeks of gestation, forming the anal canal and opening.

Disorders and Dysfunction of the Gastrointestinal Tract

A number of procedures are available to determine GI disorders. Laboratory work, such as a complete blood count (CBC) with differential, will reveal anemia, infections, and chronic illness. An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is indicative of inflammation. A comprehensive chemical panel will reveal electrolyte and chemical imbalances. X-ray studies often used include GI series, barium enema, and flat plates of the abdomen. Endoscopy allows direct visualization of the GI tract through a flexible lighted tube. Upper endoscopy permits visualization and biopsy of the esophagus, the stomach, and the duodenum. It is also valuable to remove foreign objects and cauterize bleeding vessels. Visualization of the bile and pancreatic ducts is also possible through endoscopy. The lower colon is inspected by sigmoidoscopy. Colonoscopy provides visualization of the entire colon to the ileocecal valve. Stool cultures and rectal biopsy are also important diagnostic tools. Ultrasonography is a noninvasive procedure useful in visualizing intestinal organs and masses, particularly of the liver and pancreas. Some liver function blood tests include alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT). Liver biopsy may also be indicated. Overall malabsorption tests, such as the 72-hour fecal fat test and the Schilling test (which can determine the absorption capacity of the lower ileum) are also useful. For more detailed information concerning preparation for various tests, refer to a laboratory diagnostics textbook.

Symptoms of GI disorders may be manifested by systemic signs such as failure to thrive (FTT; failure to develop according to established growth parameters such as height, weight, and head circumference) or jaundice. Pruritus (itching) in the absence of allergy may indicate liver dysfunction. Local manifestations of a GI disorder include pain, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, rectal bleeding, and hematemesis.

Nursing intervention focuses on providing adequate nutrition and freedom from infection, which can result from malnutrition or depressed immune function. Developmental delays in children should be investigated to determine whether they are related to the GI system. Skin problems in these patients may be related to pruritus from liver disease, irritation from frequent bowel movements, or other disorders. Pain and discomfort may occur during acute episodes; however, they may also result from medication side effects, or they may be referred pain. Cleft lip and cleft palate are discussed in Chapter 14. Anorexia is discussed in Chapter 33, and necrotizing enterocolitis is discussed in Chapter 13. Oral care in health and illness is discussed in Chapter 15.

Congenital Disorders

Esophageal Atresia (Tracheoesophageal Fistula)

Pathophysiology.

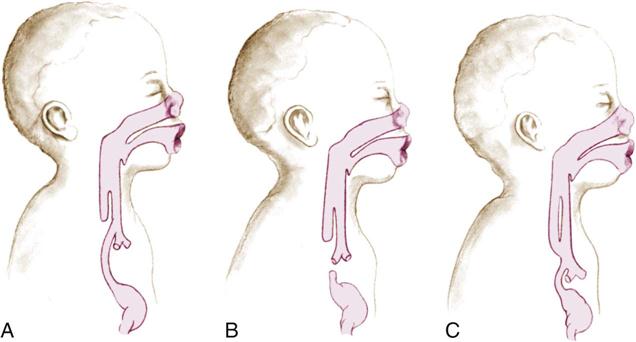

Atresia of the esophagus (tracheoesophageal fistula [TEF]) is caused by a failure of the tissues of the GI tract to separate properly from the respiratory tract early in prenatal life. There are four types of TEF:

The diagnosis of this condition is based on clinical manifestations and confirmed by x-ray study (Figure 28-2).

Manifestations.

The earliest sign of TEF occurs prenatally when the mother develops polyhydramnios. When the upper esophagus ends in a blind pouch, the fetus cannot swallow the amniotic fluid, resulting in an accumulation of fluid in the amniotic sac (polyhydramnios). At birth the infant will vomit and choke when the first feeding is introduced. Because the upper end of the esophagus ends in a blind pouch, the newborn cannot swallow accumulated secretions and will appear to be drooling. Although drooling after age 3 months is related to teething, drooling in a newborn is pathological and is related to atresia. If the upper esophagus enters the trachea, the first feeding will enter the trachea and result in coughing, choking, cyanosis, and apnea. If the lower end of the esophagus (from the stomach) enters the trachea, air will enter the stomach each time the infant breathes, causing abdominal distention.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

The nursing goals involve preventing pneumonia, choking, and apnea in the newborn. Assessment of every newborn during the first feeding is essential. The first feeding usually consists of clear water or colostrum (if breastfed) to minimize the seriousness of aspiration should it occur. If symptoms are noted, the infant is placed on NPO status (nothing by mouth), suctioned to clear the airway, and positioned to drain mucus from the nose and throat. Surgical repair is essential for survival.

Imperforate Anus

Pathophysiology.

Imperforate anus occurs in about 1 of every 5000 live births. The lower GI tract and the anus arise from two different tissues. Early in fetal life the two tissues meet and join; the tissue separating them then perforates, allowing for a passageway between the lower GI tract and the anus. When this perforation does not take place, the lower end of the GI tract and the anus end in blind pouches. This is called imperforate anus. There are four types of imperforate anus, ranging from a stenosis to complete separation or failure of the anus to form.

Manifestations.

A routine part of the newborn assessment is determining the patency of the anus. Often the first temperature of the newborn is taken rectally to ascertain patency. (All subsequent and routine temperature readings are usually taken via the axillary route.) Failure to pass meconium in the first 24 hours must be reported. Infants should not be discharged to the home before a meconium stool is passed.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Once a diagnosis of imperforate anus is established, the infant is given nothing by mouth and is prepared for surgery. Diagnosis is confirmed by x-ray study or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The initial surgical procedure may be a colostomy. Subsequent surgery can reestablish the patency of the anal canal.

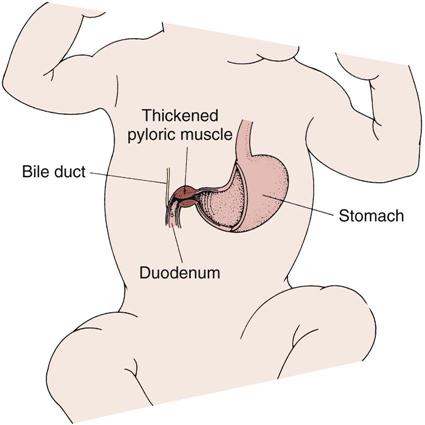

Pyloric Stenosis

Pathophysiology.

Pyloric stenosis (narrowing) is an obstruction at the lower end of the stomach (pylorus) caused by an overgrowth (hypertrophy) of the circular muscles of the pylorus or by spasms of the sphincter. This condition is commonly classified as a congenital anomaly; however, its symptoms do not appear until the infant is 2 or 3 weeks old. Pyloric stenosis is the most common surgical condition of the digestive tract in infancy (Figure 28-3). Its incidence is higher in boys than in girls, and it has a tendency to be inherited.

Manifestations.

Vomiting is the outstanding symptom of this disorder. The force progresses until most of the food is ejected a considerable distance from the mouth. This is termed projectile vomiting, and it occurs immediately after feeding. The vomitus contains mucus and ingested milk. The infant is constantly hungry and will eat again immediately after vomiting. Dehydration as evidenced by sunken fontanelle, inelastic skin, and decreased urination, as well as malnutrition, can develop. An olive-shaped mass may be felt in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Ultrasonography or scintiscans are commonly used today for diagnostic purposes, because they are noninvasive and accurate. In severe cases the outline of the distended stomach and peristaltic waves are visible during feeding.

Treatment.

The surgery performed for pyloric stenosis is called a pyloromyotomy (pylorus, myo, “muscle,” and tomy, “incision of”). The surgeon incises the pyloric muscle to enlarge the opening so food may easily pass through it again. This is done as soon as possible if the infant is not dehydrated.

Nursing Care.

The dehydrated infant is given intravenous (IV) fluids preoperatively to restore fluid and electrolyte balance. If this is not done, shock may occur during surgery. Thickened feedings may be given until the time of operation in hopes that some nutrients will be retained. The physician prescribes the degree of thickness of the formula, which is given by teaspoon or through a nipple with a large hole. The infant is burped before as well as during feedings to remove any gas accumulated in the stomach. The feeding is done slowly, and the infant is handled gently and as little as possible. The infant is placed on the right side after feedings to facilitate drainage into the intestine. Fowler’s position is preferred to aid gravity in passing milk through the stomach (see Fowler’s sling, p. 656). If vomiting occurs, the nurse may be instructed to refeed the infant. Charting of the feeding includes time, type, and amount offered; amount taken and retained; and type and amount of vomiting. The nurse also notes whether the infant appeared hungry after the feeding or if vomiting occurred again.

The nurse obtains and records a baseline weight and weighs the infant at about the same time each morning. Other factors to be charted include the type and number of stools and the color of urine and frequency of voiding (intake and output). Position is changed frequently, because the infant is weak and vulnerable to pneumonia. All procedures designed to protect from infection must be strictly carried out.

The care of the infant after surgery includes a careful observation of vital signs and the administration of IV fluids. The wound site is inspected frequently (see Chapter 22 for postoperative care). The surgery involves cutting into the hypertrophied muscle but not through the mucous membrane of the bowel; therefore the infant will not need nasogastric decompression postoperatively and will be able to resume oral feedings shortly after recovering from anesthesia. The physician prescribes oral feedings of small amounts of glucose water that gradually increase until a regular formula can be taken and retained. Overfeeding is avoided, and the nurse reviews feeding techniques with parents. The diaper is placed low over the abdomen to prevent contamination of the wound site (Clinical Pathway 28-1).

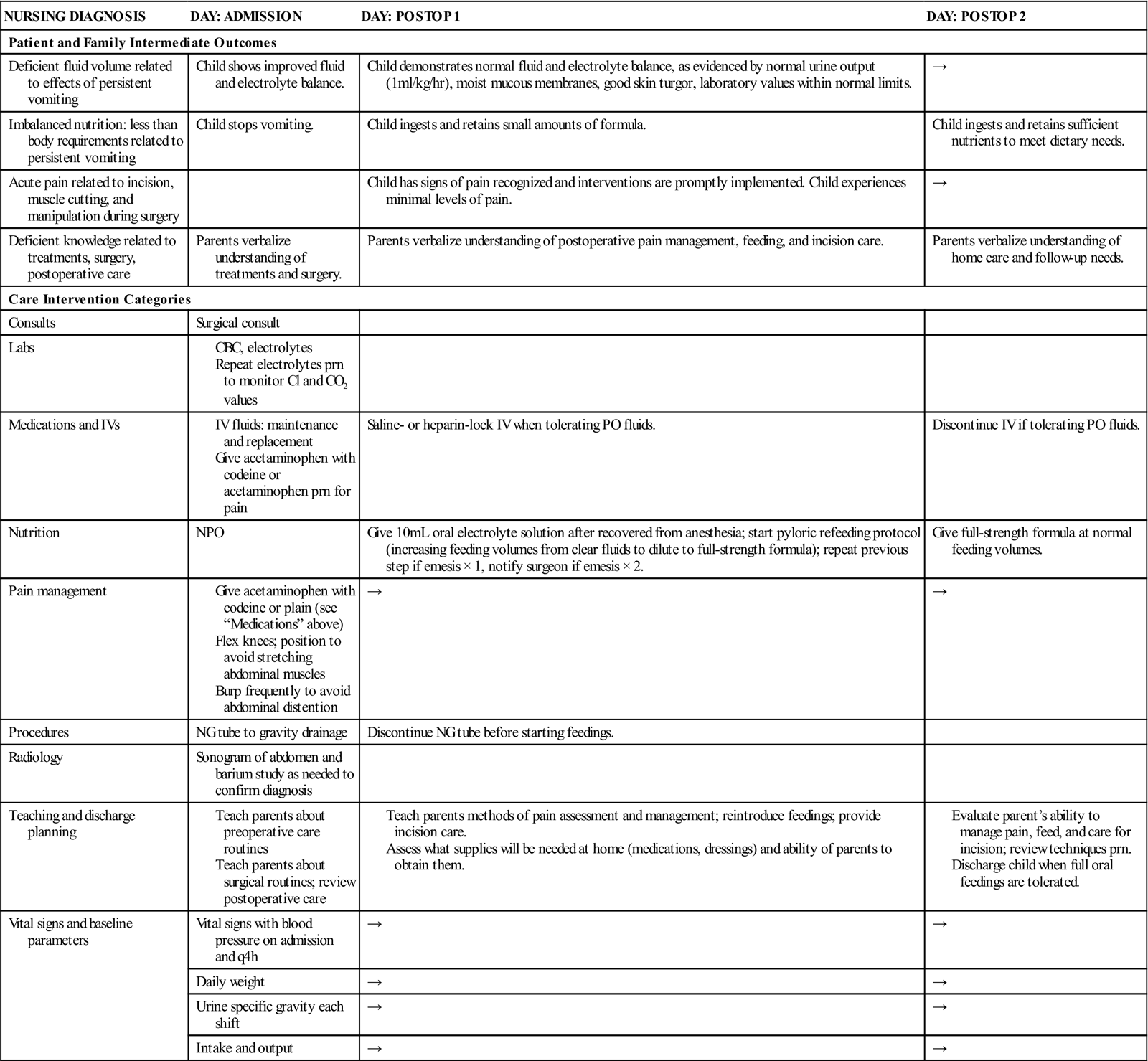

Clinical Pathway 28-1

An Interdisciplinary Plan of Care for the Infant with Pyloric Stenosis

Modified from Bowden, V., Dickey, S., & Greenberg, C. (1998). Children and their families: The continuum of care. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Celiac Disease

Pathophysiology.

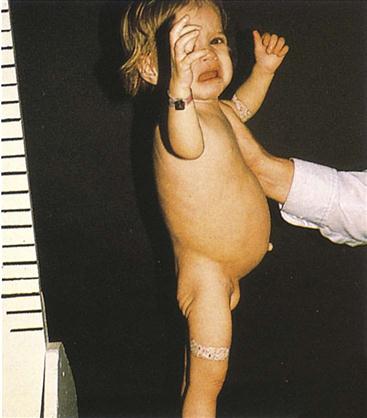

Celiac disease is also known as gluten enteropathy and sprue and is the leading malabsorption problem in children. The cause is thought to be an inherited disposition with environmental triggers (Figure 28-4).

Manifestations.

Symptoms are not evident until 6 months to 2 years of age, when foods containing gluten are introduced to the infant. Gluten is found in wheat, barley, oats, and rye. Repeated exposure to gluten damages the villi in the mucous membranes of the intestine, resulting in malabsorption of food. The infant presents with failure to thrive. Stools are large, bulky, and frothy because of undigested contents. The infant is irritable. Diagnosis is confirmed by serum immunoglobin A (IgA) test and small bowel biopsy. The characteristic profile of a child with a malabsorption syndrome is abdominal distention with atrophy of the buttocks.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

The treatment involves a lifelong diet restricted in wheat, barley, oats, and rye. It is a nursing challenge to teach the family the importance of dietary compliance. A professional nutritionist or dietitian can aid in identifying foods that are gluten free. Long-term bowel pathology can occur if dietary compliance is not lifelong.

Hirschsprung’s Disease (Aganglionic Megacolon)

Pathophysiology.

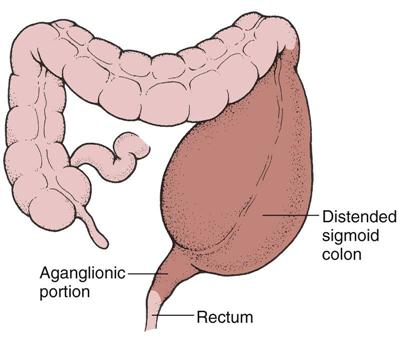

Hirschsprung’s disease, or aganglionic megacolon, occurs when there is an absence of ganglionic innervation to the muscle of a segment of the bowel. This usually happens in the lower portion of the sigmoid colon. Because of the absence of nerve cells, there is a lack of normal peristalsis. This results in chronic constipation. Ribbonlike stools are seen as a result of feces passing through the narrow segment. The portion of the bowel nearest to the obstruction dilates, causing abdominal distention (Figure 28-5). It is seen more often in boys than girls and has familial tendencies. The incidence is approximately 1 in 5000 live births. There is a higher incidence in children with Down syndrome. The condition may be acute or chronic.

Manifestations.

In the newborn, failure to pass meconium stools within 24 to 48 hours may be a symptom of Hirschsprung’s disease. In the infant, constipation, ribbonlike stools, abdominal distention, anorexia, vomiting, and failure to thrive may be evident. Often the parent brings the young child to the clinic after trying several over-the-counter laxatives to treat the constipation without success. If the child is untreated, other signs of intestinal obstruction and shock may be seen. The development of enterocolitis (inflammation of the small bowel and colon) is a serious complication. It may be signaled by fever, explosive stools, and depletion of strength. Diagnostic evaluation usually includes a barium enema and rectal biopsy, which shows a lack of innervation. Anorectal manometry tests the strength of the internal rectal sphincter. In this procedure a balloon catheter is placed into the rectum, and the pressure exerted against it is measured.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Megacolon is treated by surgery. The impaired part of the colon is removed, and an anastomosis of the intestine is performed. In newborns a temporary colostomy may be necessary, and more extensive repair may follow at about 12 to 18 months of age. Closure of the colostomy follows in a few months.

Nursing care is age dependent. In the newborn, detection is a high priority. As the child grows older, careful attention to a history of constipation and diarrhea is important. Signs of undernutrition, abdominal distention, and poor feedings are suspect.

Because the distended bowel in a child with megacolon provides a larger mucous membrane surface area that will come in contact with fluid inserted during an enema, an increased absorption of the fluid can be anticipated. For this reason, when a child is given an enema at home, normal saline solution, not tap water, is used. Tap water enemas in infants and small children can lead to water intoxication and death. Parents can obtain normal saline solution from the pharmacy without prescription, or they can make it at home by using one half of a teaspoon of noniodized salt in 1 cup of lukewarm tap water. The amount of fluid administered should be determined by the health care provider. The nurse stresses to parents the importance of using saline solution. Postoperative care of children is discussed in Chapter 22.

Intussusception

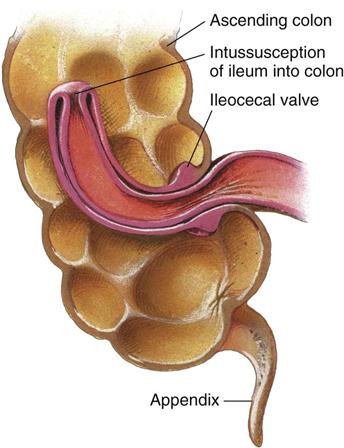

Pathophysiology.

Intussusception (intus, “within,” and suscipere, “to receive”) is a slipping of one part of the intestine into another part just below it (Figure 28-6). It is often seen at the ileocecal valve, where the small intestine opens into the ascending colon. The mesentery, a double fan–shaped fold of peritoneum that covers most of the intestine and is filled with blood vessels and nerves, is also pulled along. Edema occurs. At first this telescoping of the bowel causes intestinal obstruction, but strangulation takes place as peristalsis forces the structures more tightly. This portion may burst, causing peritonitis.

Intussusception generally occurs in boys between 3 months and 6 years of age who are otherwise healthy. Its frequency decreases after age 36 months. Occasionally the condition corrects itself without treatment. This is termed a spontaneous reduction. However, because the patient’s life is in danger, the physician does not waste time waiting for this to occur. The prognosis is good when the patient is treated within 24 hours.

Manifestations.

In typical cases the onset is sudden. The infant feels severe pain in the abdomen, as evidenced by loud cries, straining efforts, and kicking and drawing of the legs toward the abdomen. At first there is comfort between pains, but the intervals shorten and the condition becomes worse. The child vomits. The stomach contents are green or greenish yellow (this results from bile stain), and the contents are described as bilious. Bowel movements diminish, and little flatus is passed. Movements of blood and mucus that contain no feces are common about 12 hours after the onset of the obstruction; these are termed currant jelly stools. The child’s fever may run as high as 41.1° C (106° F), and signs of shock, such as sweating, weak pulse, and shallow, grunting respirations are evident. The abdomen is rigid.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Intussusception is an emergency, and because of the severity of symptoms, most parents contact a physician promptly. The diagnosis is determined by the history and physical findings. The physician may feel a sausage-shaped mass in the right upper portion of the abdomen during bimanual rectal and abdominal palpation. Abdominal films also may indicate the mass. A barium enema is the treatment of choice, with surgery scheduled if reduction is not achieved. The recurrence rate after barium enema reduction is approximately 10%.

During the operation a small incision is made into the abdomen, and the wayward intestine is “milked” back into position. The intestine is inspected for gangrene; if all is well, the abdomen is sutured. Barring complications, recovery is straightforward. If the intestine cannot be reduced or if gangrene has set in, a bowel resection is done and the affected area is removed. The cut end of the ileum is joined to the cut end of the colon; this is called an anastomosis. Routine preoperative and postoperative care is discussed in Chapter 22.

Meckel’s Diverticulum

Pathophysiology.

During fetal life the intestine is attached to the yolk sac by the vitelline duct. A small blind pouch may form if this duct fails to disappear completely. This condition is termed Meckel’s diverticulum. It usually occurs near the ileocecal valve, and it may be connected to the umbilicus by a cord. A fistula may also form. This sac is subject to inflammation, much like the appendix. This disorder is the most common congenital malformation of the GI tract. It is seen more often in boys.

Manifestations.

Symptoms may occur at any age but appear most often before 2 years of age. Painless bleeding from the rectum is the most common sign. Bright red or dark red blood is more usual than tarry stools. Abdominal pain may or may not be present. In some persons it may exist without causing symptoms. Barium enema and radionuclide scintigraphy are useful in diagnosing Meckel’s diverticulum. X-ray films are not helpful because the pouch is so small that it may not appear on the screen.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

The diverticulum is removed by surgery. Nursing care is the same as for the patient undergoing exploration of the abdomen. Because this condition appears suddenly and bleeding causes parental anxiety, emotional support is of particular importance.

Hernias

Pathophysiology.

An inguinal hernia is a protrusion of part of the abdominal contents through the inguinal canal in the groin. It is more common in boys than in girls. It is also commonly seen in preterm infants. An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of a portion of intestine through the umbilical ring (an opening in the muscular area of the abdomen through which the umbilical vessels pass, Figure 28-7). This type of hernia appears as a soft swelling covered by skin, which protrudes when the infant cries or strains. Hernias may be present at birth (congenital) or may be acquired, and they can vary in size. A hernia is called reducible if it can be put back into place by gentle pressure; if this cannot be done, it is called an irreducible or an incarcerated hernia. Incarceration (constriction) occurs more often in infants under 10 months of age. Hernias may be bilateral.

Manifestations.

The infant with a hernia may be relatively free of symptoms. Irritability, fretfulness, and constipation are sometimes evident. The diagnosis is made when physical examination shows a mass in the area that reappears from time to time, particularly when the child cries or strains. A strangulated hernia occurs when the intestine becomes caught in the passage and the blood supply is diminished. This happens more often during the first 6 months of life. Vomiting and severe abdominal pain are present. Emergency surgery is necessary if strangulation occurs, and in some cases a bowel resection is performed.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Hernias are successfully repaired by the surgical operation called a herniorrhaphy. This is a relatively simple procedure and is well tolerated by the child. Most children are scheduled for procedures in same-day surgery units. The benefits of this method are both economic and psychological. Parents are instructed to bring the fasting child to the hospital about 1 hour before surgery. Parents remain with the child during the entire time except during the actual procedure. They are encouraged to assist in routine postoperative care.

Often no dressing is applied to the wound. Sometimes a waterproof collodion dressing, which looks like clear nail polish, is applied. Postoperative care is directed toward keeping the wound clean. Diapers are left open for this purpose. Wet diapers are changed frequently.

Disorders of Motility

Gastroenteritis

Pathophysiology.

Gastroenteritis involves an inflammation of the stomach and the intestines; colitis involves an inflammation of the colon; enterocolitis involves an inflammation of the colon and the small intestine. The most common noninfectious causes of diarrhea involve food intolerance, overfeeding, improper formula preparation, or ingestion of high amounts of sorbitol (a substance found in sweetened “sugar-free” products). The priority problem in diarrhea is fluid and electrolyte imbalance and failure to thrive.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Treatment is focused on identifying and eradicating the cause. Nursing responsibilities include teaching parents and caregivers proper and age-appropriate diet and feeding techniques. The priority goal of care includes preventing fluid and electrolyte imbalance.

Oral rehydrating solutions (ORS) such as Pedialyte, Lytren, Ricelyte, and Resol are used for infants in small, frequent feedings. Although formula feeding is withheld, breastfeeding can accompany oral rehydration therapy (ORT) because of breast milk’s osmolarity, antimicrobial properties, and enzyme content.

The nursing care of gastroenteritis includes maintaining intake and output records and providing skin care and frequent diaper changes to prevent excoriation from the frequent stools. Parents should be taught good handwashing techniques, proper food handling, and principles of cleanliness and infection prevention. The infant should be weighed daily, observed for dehydration or overhydration, and kept warm. Transmission-based contact precautions should be used to prevent the spread of infection (see Appendix A). Sometimes parents need help in interpreting food labels to avoid foods to which their child may be allergic. Table 28-1 lists some terms that often need clarification for the parents of a child who is food intolerant.

Table 28-1

| INGREDIENT LISTED | MAY CONTAIN THIS: |

| Binder | Egg |

| Bulking agent | Soy |

| Casein | Cow’s milk (often in canned tuna) |

| Coagulant | Egg |

| Emulsifier | Egg |

| Protein extender | Soy |

Vomiting

Pathophysiology.

Vomiting, a common symptom during infancy and childhood, results from sudden contractions of the diaphragm and the muscles of the stomach. It must be evaluated in relation to the child’s overall health status. Persistent vomiting requires investigation because it results in dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. The continuous loss of hydrochloric acid and sodium chloride from the stomach can cause alkalosis. In this condition the acid-base balance of the body becomes disturbed because of a loss of chlorides and potassium. This can result in death if left untreated.

Manifestations.

The child may vomit from various causes. Some stem from improper feeding techniques that should be assessed by the nurse. Sometimes the difficulty lies with formula intolerance. The introduction of foods of a different consistency may also precipitate this symptom.

Other causes of vomiting are systemic illness such as increased intracranial pressure or infection. Aspiration pneumonia is a serious complication of vomiting. In aspiration, vomitus is drawn into the air passages on inspiration, causing immediate death in extreme cases. Health professionals and laypersons should become familiar with lifesaving procedures such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for use in such emergencies.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

To prevent vomiting the nurse must carefully feed and burp the infant. Treatments are avoided immediately after feedings. The infant is handled as little as possible after feedings. To prevent aspiration of vomitus the nurse places the infant on the right side following feedings. When an older child begins to vomit, the head is turned to one side, and an emesis basin and tissues are provided.

Factors to be charted include time, amount, color (e.g., bloody, bile-stained), consistency, force, frequency, and whether or not vomiting was preceded by nausea or by feedings. IV fluids may be given. Oral fluids are withheld for a short time to allow the stomach to rest. Gradually, sips of water are given according to the infant’s tolerance and condition. The infant’s intake and output are carefully recorded so the physician is able to compare the urine output with the total fluid intake.

Drugs such as trimethobenzamide (Tigan) or promethazine (Phenergan) may be prescribed when vomiting is persistent. They are available in rectal suppository form. The nurse lubricates the suppository and inserts it into the rectum, where it dissolves. Slight pressure is exerted over the anus for a short time to ensure that the suppository is not expelled. Charting includes the time administered and whether or not vomiting subsided.

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Pathophysiology.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER, or chalasia) results when the lower esophageal sphincter is relaxed or not competent, which allows stomach contents to be easily regurgitated into the esophagus.

The term chalasia is derived from the Greek word chalasis, which means “relaxation.” Although many infants have this condition to a small degree, about 1 in 300 to 1 in 1000 have significant reflux and associated complications. The condition is associated with neuromuscular delay and is often seen in preterm infants and children with neuromuscular disorders, such as cerebral palsy and Down syndrome. In many infants the symptoms decrease around age 12 months, when the child stands upright and eats more solid foods.

Manifestations.

Symptoms include vomiting, weight loss, and failure to thrive. The vomiting occurs within the first and second weeks of life. The infant is fussy and hungry. Respiratory problems can occur when vomiting stimulates the closure of the epiglottis and the infant presents with apnea. Aspiration of vomitus can also occur.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

A careful history is taken. Of particular interest is when the vomiting started, type of formula, type of vomiting, feeding techniques, and the infant’s eating in general. Tests used to determine the presence of GER include scintigraphy, which involves the infant drinking a radioactively labeled formula and following the path of the fluid with imaging studies to determine the presence of reflux or poor swallowing coordination. Prolonged esophageal pH monitoring is one of the most definitive diagnostic tests and helps to determine the acuity of the disease and the course of treatment to prevent esophagitis.

Therapy depends on the severity of symptoms. Most parents need only reassurance and education about feeding the infant. Teaching should include careful burping, avoiding overfeeding (which distends the stomach), and proper positioning. A general guide to determine optimum intake to prevent gastric distention is to feed the infant no more than the age in months plus 3, every 3 to 4 hours. For example, a 3-month-old infant should be fed a maximum of 6 oz in one feeding (Weill, 2008).

Medication and surgical intervention may be required in infants with more complicated gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD). Parents are instructed to burp the infant frequently. Feedings can be thickened with cereal (1 teaspoon to 1 tablespoon of cereal per ounce of formula). Adding cereal to the formula increases the caloric density from 20 calories per ounce to 27 calories per ounce. The formula Enfamil AR is a milk-based formula with added rice starch for thickness, that provides 20 calories per ounce (see Table 16-3).

After being fed, the infant should be placed in an upright position or propped on the right side. The body is inclined about 30 to 40 degrees, and the infant is held in place by a Fowler’s sling (Figure 28-8). Sitting upright in an infant seat or swing is not recommended because it increases intraabdominal pressure. The upright prone position has been recommended for the infant with GER when awake and monitored. (The supine [back] sleep position is recommended for all healthy infants.) Medications that relax the pyloric sphincter and promote stomach emptying may be used, such as metoclopramide (Reglan). The medication must be administered before meals. Side effects such as drowsiness or restlessness can occur. Ranitidine (Zantac) may be prescribed to reduce stomach acid and prevent the development of esophagitis. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole (Prilosec) and lansoprazole (Prevacid) are awaiting U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in infants.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree