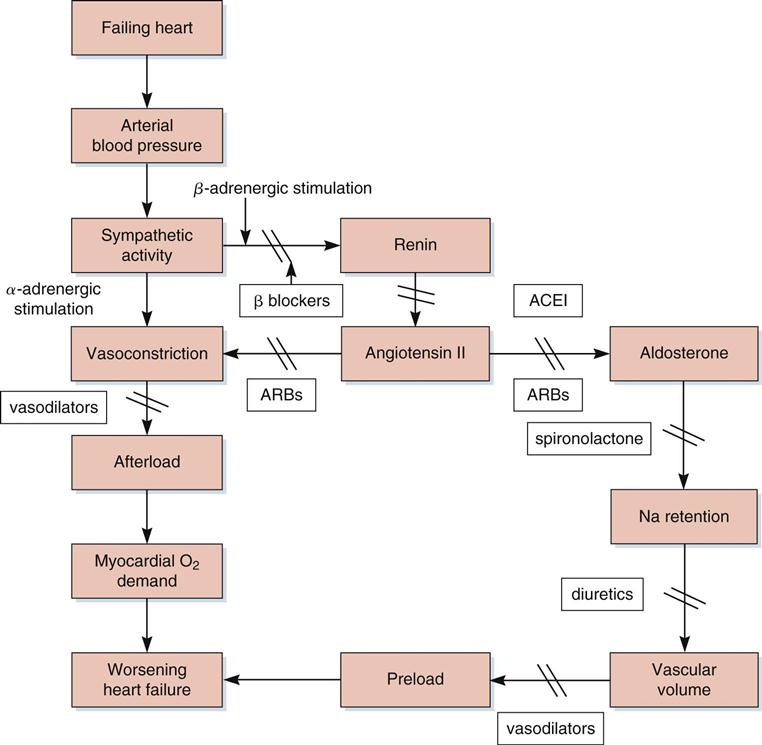

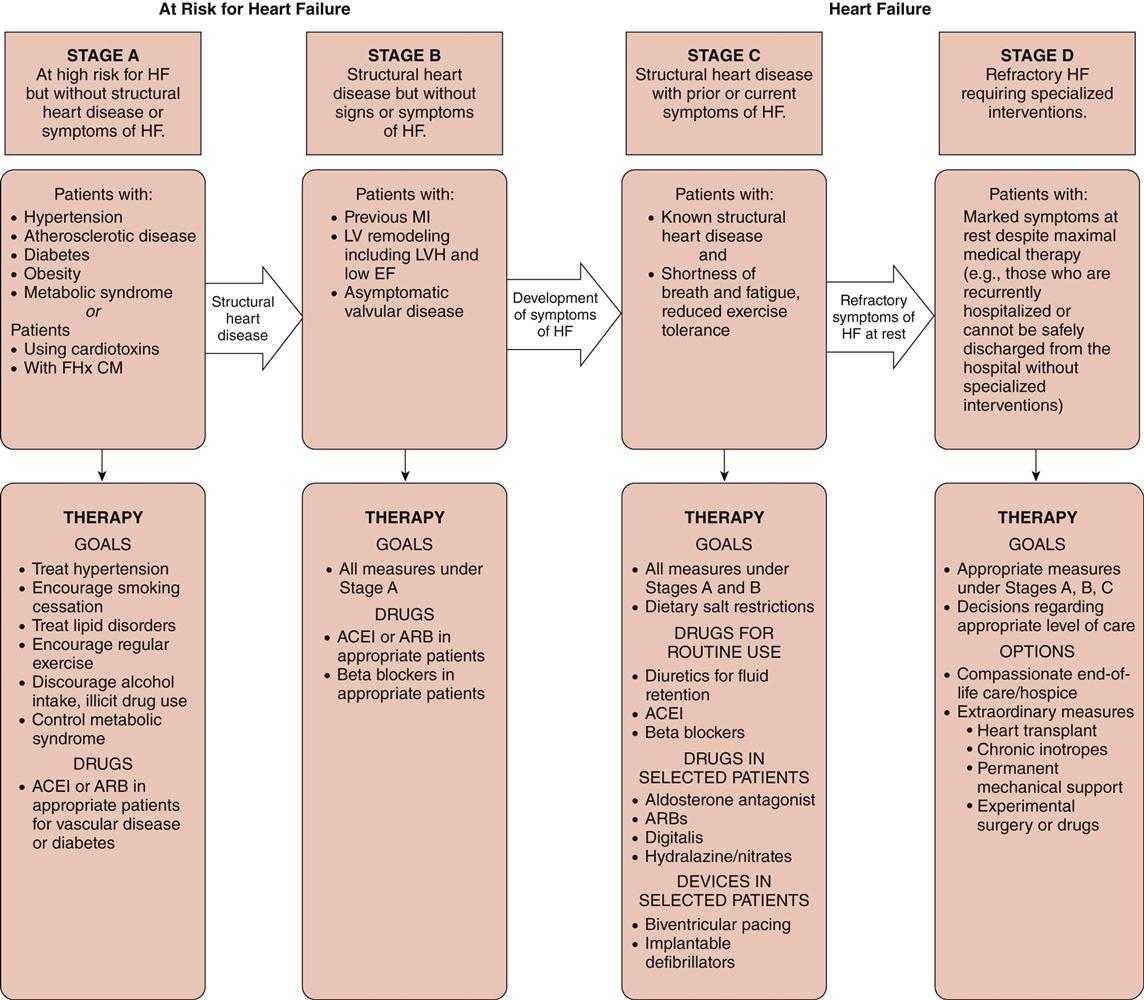

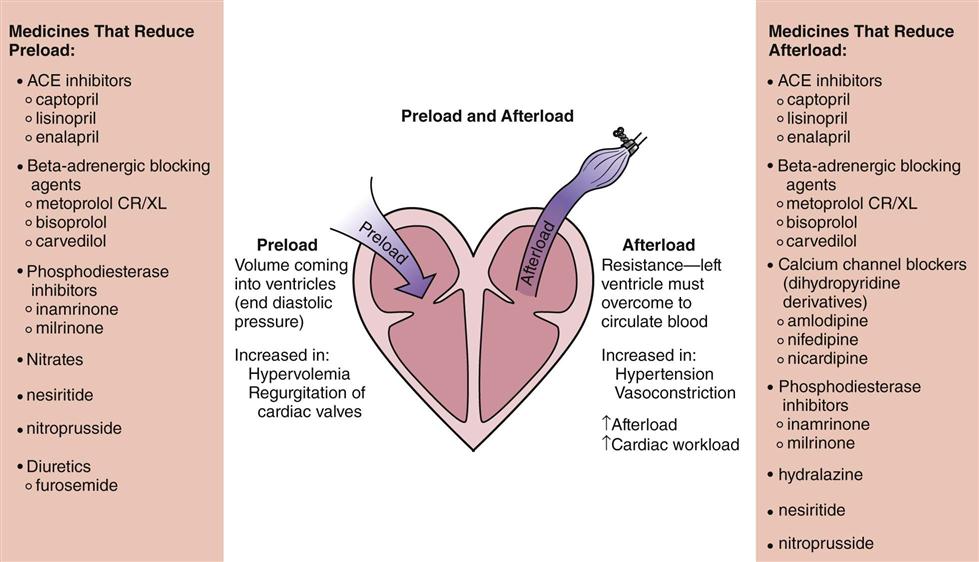

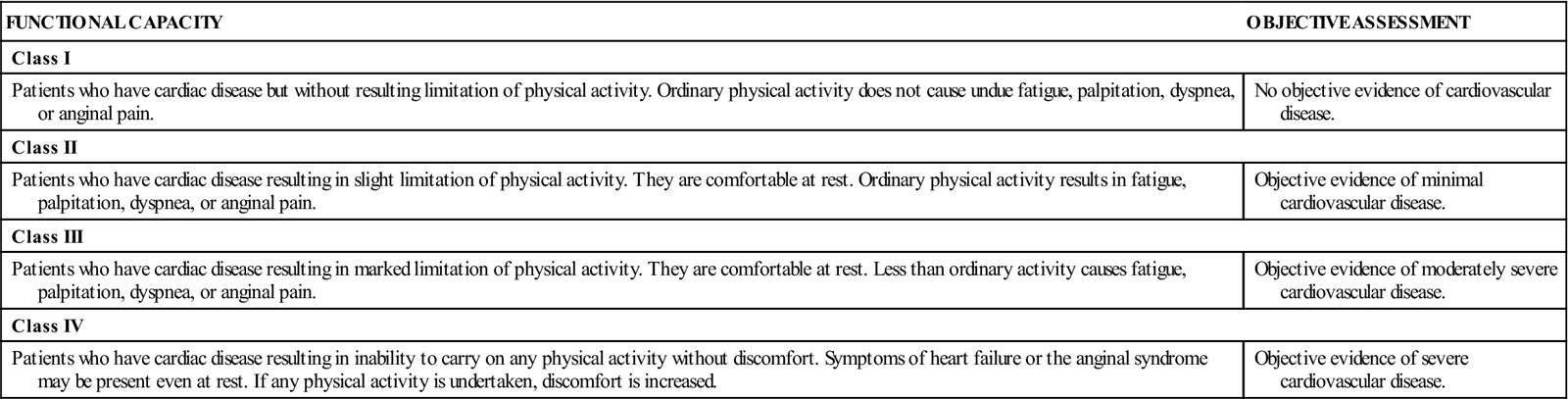

1 Summarize the pathophysiology of heart failure, including the body’s compensatory mechanisms. 2 Identify the goals of treatment of heart failure. 4 Describe digoxin toxicity and ways to prevent it. 5 Explain the nursing assessments needed to monitor for digoxin toxicity. systolic dysfunction ( diastolic dysfunction ( inotropic agents ( digitalis toxicity ( positive inotropy ( negative chronotropy ( digitalization ( The incidence of heart failure (previously known as congestive heart failure)—unlike that of other cardiovascular diseases—continues to increase as a result of population aging and improved survival after acute myocardial infarction. It is estimated that 1% of people older than age 65 and 10% of those older than age 75 experience heart failure. Some 5.7 million Americans have this disabling condition; more than 670,000 patients develop symptoms annually, and more than 200,000 people die from heart failure each year. The 5-year mortality rate for heart failure is approximately 50%. The economic burden is staggering, with an estimated total cost of $39 billion for managing heart failure as a primary diagnosis in the United States in 2010 (Roger, 2010). Heart failure involves a cluster of signs and symptoms that arise when the left or right ventricle or both ventricles lose the ability to pump enough blood to meet the body’s circulatory needs. The most common type of heart failure is systolic dysfunction (also known as contracting dysfunction). Normally, the heart pumps at a rate that supports the body’s need for blood flow and the oxygenation of the vital organs and muscles. Systolic heart failure results when the heart lacks sufficient force to pump all the blood (resulting in decreased cardiac output) with which it is presented to meet the body’s oxygenation needs (causing decreased tissue perfusion). Early clinical symptoms are decreased exercise tolerance and poor perfusion to the peripheral tissues. As the condition progresses, the left ventricle chamber enlarges (left ventricular hypertrophy), and an increase in blood volume is required to fill the expanding ventricle to maintain cardiac output. Causes of systolic dysfunction are those that cause damage to the heart muscle itself. The most common is coronary artery disease that leads to myocardial infarction. Other causes include dysrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, and congenital heart disease. Usually the left ventricle fails first; however, with progression of the disease, the right ventricle also enlarges because of increased pulmonary resistance and it eventually fails. Diastolic dysfunction (or filling dysfunction) causes heart failure because the left ventricle develops a “stiffness” and fails to relax enough between contractions to allow adequate filling before the next contraction. Symptoms of diastolic dysfunction include pulmonary congestion and peripheral edema. There are many reasons why diastolic dysfunction develops, including constrictive pericarditis, ventricular muscle hypertrophy caused by chronic hypertension, valvular heart disease that results in flow resistance, and aortic stenosis. The general pathogenesis of heart failure is diagrammed in Figure 28-1. When the vital organs and peripheral tissues are not adequately perfused, compensatory mechanisms begin to overcome the inadequate output of the heart. The sympathetic nervous system releases epinephrine and norepinephrine, which produce tachycardia and increase contractility. The increased sympathetic stimulation also increases peripheral vasoconstriction, which results in an increased afterload against which the heart must pump, causing a further decrease in cardiac output (see Figure 28-1). The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system stimulates renal distal tubule sodium and water retention in an effort to increase circulating blood volume, which increases preload to the heart. There is also an increased production of vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) from the pituitary gland that increases water recovery from the kidneys and increases intravascular volume and preload. With decreased perfusion secondary to low cardiac output, the kidneys also increase sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubules to help expand circulating blood volume. The increased intravascular volume initially improves tissue perfusion; however, over time, excessive amounts of sodium and water are retained, causing increased pressure within the capillaries and resulting in edema formation. Early symptoms of heart failure vary depending on the underlying cause of the disease. Traditionally, the signs and symptoms of heart failure have been classified on the basis of whether failure is developing in the right ventricle or the left ventricle. However, it has been found that the symptoms overlap to such an extent because of the complexity of the syndrome that it is difficult to attribute a particular clinical indicator to a specific ventricle. It is also important to recognize that the clinical indicators vary considerably over time in response to the treatments being applied (Box 28-1). The goals for treating heart failure are to reduce the signs and symptoms associated with fluid overload, increase exercise tolerance, and prolong life. If the heart failure is acute, the patient must be hospitalized for a diagnostic workup to determine the underlying cause. The New York Heart Association Functional Classification System is commonly used to group patients with heart failure according to the degree of impairment (Table 28-1). Figure 28-2 illustrates an updated classification scheme that includes treatment guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. Heart failure is treated by correcting the underlying disease (e.g., coronary artery disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, thyroid disease), smoking cessation, regular exercise when able, bed rest when necessary, following a sodium-restricted diet, and controlling symptoms with a combination of pharmacologic agents. Health care institutions are evaluated according to the core measures that promote quality outcomes for patients with heart failure. These include providing discharge education that is specific to the disease management of heart failure as well as to smoking cessation; measuring left ventricular function during hospitalization; prescribing an angiotensin-converting (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) for patients with left ventricular dysfunction; and reporting the 30-day mortality rate of patients with heart failure. Table 28-1 New York Heart Association Functional Classification System From The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association: Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of diseases of the heart and great vessels, ed 9, Boston, 1994, Little Brown. Requests for reprints should be sent to the Office of Scientific Affairs, American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231-4596. Heart failure is treated with a combination of vasodilator, diuretic, and inotropic therapy (see Figure 28-1). If the failure is acute, most therapy will be administered by the intravenous (IV) route in an intensive care unit. Vasodilators are used to reduce the strain on the left ventricle by reducing the systemic vascular resistance (afterload) against which the left ventricle is working. The reduced vascular resistance will also increase tissue perfusion to vital organs and muscles. The second goal of vasodilator use is to reduce preload so that the high volume of blood returning to the heart is decreased. The reduction in preload decreases pulmonary congestion and allows the patient to breathe more easily (Figure 28-3). As renal perfusion is improved, potent diuretics are administered to enhance sodium and water excretion. This provides substantial symptomatic relief to the patient in addition to reducing the workload on the heart. Inotropic agents stimulate the heart to increase the force of contractions, thereby boosting cardiac output. This also helps reduce pulmonary congestion and improve tissue perfusion. Intravenous nitroglycerin (see Chapter 25), nitroprusside (see Chapter 23), and nesiritide are used as vasodilators to reduce preload and afterload in critically ill patients. ACE inhibitors are the mainstays of oral vasodilator therapy for treating chronic heart failure. Most patients with heart failure require a loop diuretic such as furosemide or bumetanide (see Chapter 29) to help reduce fluid and sodium overload. Studies have indicated that certain patients will also benefit from the use of beta-adrenergic blocking agents. A major component of the pathophysiologic causes of heart failure is increased sympathetic activity. Carvedilol, a noncardioselective beta blocker and an alpha-1 blocker, blocks adrenergic activity while lowering systemic vascular resistance as a vasodilator (see Chapters 13 and 23). Other vasodilators used include minoxidil and hydralazine (see Chapter 23). The dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine, amlodipine, nicardipine) may be used to reduce afterload in patients with heart failure; however, the nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (especially diltiazem and verapamil) also have negative inotropic properties that can aggravate heart failure in certain patients (see Chapters 23 and 25). A combination product containing hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate (BiDil) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This combination has been shown to reduce hospitalizations, improve quality of life, and reduce mortality among African Americans with hypertension and heart failure. Guidelines also recommend that angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (see candesartan, Chapter 23) and aldosterone antagonists (see eplerenone, Chapter 23; and spironolactone, Chapter 29) may provide additional benefit for patients who are still symptomatic while receiving full therapeutic doses of an ACE inhibitor and a beta blocker or those who have developed adverse effects from the standard therapies. Inotropic agents used to treat acute failure include IV dobutamine (see Chapter 13), inamrinone, and milrinone. Digoxin, a digitalis glycoside, has been used for decades to treat heart conditions when an oral inotropic agent is needed. Obtain the patient’s history of prior treatment for heart disease, related cardiovascular disease (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia), diabetes mellitus, and lung disease. Obtain details of all medications that have been prescribed to the patient. Tactfully determine whether the prescribed medications are being taken regularly. If they are not being taken, ask why not? Ask the patient for a list of all over-the-counter medications and any herbal products being taken. Perform focused assessments to determine the effectiveness and the adverse effects of any pharmacologic interventions.

Drugs Used to Treat Heart Failure

Objectives

Key Terms

) (p. 443)

) (p. 443)

) (p. 443)

) (p. 443)

) (p. 447)

) (p. 447)

) (p. 450)

) (p. 450)

) (p. 452)

) (p. 452)

) (p. 452)

) (p. 452)

) (p. 452)

) (p. 452)

Heart Failure

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Clayton

Treatment of Heart Failure

FUNCTIONAL CAPACITY

OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT

Class I

Patients who have cardiac disease but without resulting limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or anginal pain.

No objective evidence of cardiovascular disease.

Class II

Patients who have cardiac disease resulting in slight limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or anginal pain.

Objective evidence of minimal cardiovascular disease.

Class III

Patients who have cardiac disease resulting in marked limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary activity causes fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea, or anginal pain.

Objective evidence of moderately severe cardiovascular disease.

Class IV

Patients who have cardiac disease resulting in inability to carry on any physical activity without discomfort. Symptoms of heart failure or the anginal syndrome may be present even at rest. If any physical activity is undertaken, discomfort is increased.

Objective evidence of severe cardiovascular disease.

Drug Therapy for Heart Failure

Actions

Uses

![]() Nursing Implications for Heart Failure Therapy

Nursing Implications for Heart Failure Therapy

Assessment

History of Heart Disease.

Medication History.

History of Six Cardinal Signs of Heart Disease

Indications of Altered Cardiac Function

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

28. Drugs Used to Treat Heart Failure

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree