CHAPTER 26. Alternative Infusion Access Devices

Marilyn Parker, MSN, ACHPN, ACNS, BC and Karin Henderson, MSN, RN, CCRN, CS-GNP

When intravenous (IV) access cannot be obtained because of lack of time, inadequate skills, or patient condition, vascular access by subcutaneous or intraosseous administration are alternative infusion options.

CONTINUOUS SUBCUTANEOUS INFUSION

OVERVIEW

Continuous subcutaneous infusion (CSI) is a useful route for the administration of selected medications. CSI can provide a comfortable, less expensive alternative to traditional IV administration or intramuscular (IM) injections, and can provide patients the added flexibility of receiving prescribed therapies without having to endure venipuncture attempts or painful IM injections. CSI should be considered an option for patients experiencing the following: limited or no venous access, inability to tolerate the burdens of oral therapies (numerous pills), oral therapies not as effective for symptom control or disease management (peak and trough effect), those with a single venous access device (VAD) and incompatible medications, those with medications adaptable to CSI, and patients without a functioning gastrointestinal tract. CSI can be effectively administered in a variety of patient care settings: home care, long-term care, intermediate care, acute care/hospitals, and hospice environments. CSI is used in many settings because it enables patients to manage their illness and/or pain without the risks and expenses involved with IV medication administration (Perry and Potter, 2006).

STRUCTURE OF THE SKIN: A BRIEF REVIEW

As the outermost protective layer, the skin is the largest organ of the body. It plays a major role in homeostasis by serving as a barrier to organisms, regulating body temperature, and maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance. Changes in the skin can also communicate information about a person’s health and well-being (Cuzell and Workman, 2006). The thinnest outer layer is the epidermis, less than 1 millimeter (mm) thick; it is able to act effectively as the protective barrier between the body and environment. The epidermis does not have a separate blood supply, but receives nutrients from the dermis by diffusion. The dermis is the layer of connective tissue between the epidermis and fat layer (also known as the subcutaneous tissue layer). The dermis is an interwoven network of collagen and elastic fibers that give the skin flexibility and strength. The dermis also contains a network of capillaries, lymph vessels, and sensory nerves that promotes oxygen and heat exchange and the transmission of sensation (Cuzell and Workman, 2006). The subcutaneous layer covers muscle and bone, is the site for fat formation and storage, provides heat insulation for the body, and provides protection against injury by absorbing shock and padding internal structures. The thickness of the subcutaneous layer varies with body surface area, age, and gender. Many blood vessels pass through the fatty layer and extend into the dermal layer, forming capillary networks that supply nutrients and remove wastes (Cuzell and Workman, 2006).

Medications and fluids are absorbed into the bloodstream through the network of capillaries and blood vessels. Subcutaneous tissue is less vascular than muscle tissue, so the onset of action is slower than intramuscular or intravenous administration (see Figure 10-1).

CONTINUOUS SUBCUTANEOUS THERAPIES

There are two major categories of continuous subcutaneous therapies: (1) continuous subcutaneous infusion of medication and (2) hypodermoclysis, or “clysis.”

Continuous subcutaneous infusion

The goal of giving medication by continuous subcutaneous infusion (CSI) is to attain appropriate blood levels of medications and achieve the desired symptom control or management of disease without the risks, expense, or inconvenience of IV therapies. The most common medications infused via this method are opioids (morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl for pain management), insulin (diabetes management), terbutaline (treatment of preterm labor), deferoxamine mesylate (iron chelation), antiemetics, and steroids. Other medications used in palliative care given by CSI include midazolam, haloperidol, and hyoscine (Negro et al, 2002). Recently, clodronate, omeprazole, and methadone have been added to this list; however, methadone is notable for causing a high incidence of tissue irritation (Neasfey, 2005).

Advantages/Disadvantages

The following are advantages of administering medication by CSI: (1) medications are absorbed directly into the bloodstream, avoiding “first pass” effects of liver metabolism; (2) opioids can be titrated rapidly for pain and symptom management; (3) burdens of oral therapy are relieved (e.g., numerous pills, inconsistent medication effects); (4) central nervous system (CNS) side effects associated with intermittent drug therapy (such as nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness) are decreased; (5) a functioning gastrointestinal tract is not required; (6) bioavailability and analgesic efficacy of medications are similar to those from IV administration; (7) therapies are available to patients with limited or nonexistent venous access, or those that have a single VAD with other incompatible medications; (8) it is generally less expensive and less time-consuming than venipuncture, and may be considered less invasive by patients (Neafsey, 2005 and Weissman, 2005); (9) clinicians can easily learn the procedure (does not require venipuncture); and (10) it can be safely administered in a variety of patient care settings, including the home (Phillips, 2005).

The major disadvantage of giving medication by CSI is that medications must be concentrated enough to be able to infuse small volumes. Most patients can absorb up to 2 to 3 mL/hour of medication (Pasero, 2002). As the rate of infusion increases, the absorption of medication decreases (Perry and Potter, 2006). Other disadvantages include local discomfort at the infusion site and limited medication choices because of pharmacokinetics and medication properties. Also, the onset of action for medication given by CSI is slower than that when IV administration is used; anticipate about 20 minutes for onset of action as compared to more immediate onset of action when administered by the IV route. Anything affecting local blood flow to the tissues, such as exercise, local application of hot or cold compresses, or altered body temperature, influences the rate of drug absorption (Perry and Potter, 2006). CSI is contraindicated in patients with conditions resulting in decreased local tissue perfusion, such as circulatory shock, hypothermia, and occlusive vascular disease (Perry and Potter, 2006).

Hypodermoclysis

Hypodermoclysis, or “clysis,” is the infusion of isotonic fluids into the subcutaneous space for the treatment or prevention of dehydration in the elderly adult (Walsh, 2005).

Because of severe adverse reactions related to the misuse of electrolyte-free or hypertonic solutions in the 1950s, hypodermoclysis was almost completely discontinued. Since the late 1980s, this method has been increasingly rediscovered as an alternative therapy for IV rehydration, especially in the fields of geriatric and palliative medicine (Slesak et al, 2003). In long-term care, the common treatment for patients unable to take adequate fluids by mouth is infusion of IV solutions (Remington and Hultman, 2007), which often necessitates moving the patient to a different level of care, such as the clinic or hospital. With hypodermoclysis, isotonic fluids are infused into the subcutaneous space through a small gauge needle inserted at various sites, including the thighs, back, abdomen, and arms. Fluids can be infused using gravity or a pump at rates of 20 to 125 mL/hr. Over 24 hours, up to 1.5 L can be delivered at one site or 3 L using two sites. Hyaluronidase, an enzyme, may or may not be added to facilitate absorption (Remington and Hultman, 2007).

Advantages/Disadvantages

The following are advantages of hypodermoclysis: (1) it can be administered, after training, in a variety of patient care settings, including the home; (2) it appears to be well accepted by patients and is cost-effective when compared to IV therapy (Slesak et al, 2003); (3) it avoids the need to transfer the patient to another setting; and (4) it does not require venipuncture. The following are disadvantages: (1) local site discomfort or edema, (2) limited application in certain patient conditions, and (3) not effective in emaciated or hypoalbuminemic patients who are edematous. Hypodermoclysis is contraindicated in emergency situations and for patients needing immediate fluid replacement, patients needing large-volume fluid replacement, and patients who require electrolyte-free or hypertonic solutions (Walsh, 2005). Patients with bleeding disorders or skin conditions limiting suitable sites for access device placement are not candidates for hypodermoclysis (Walsh, 2005). Hypodermoclysis is also contraindicated when the patient may be at increased risk for pulmonary congestion or edema, such as severe congestive heart failure (Sasson and Shvartzman, 2001).

ASSESSMENT OF PATIENT BEFORE THERAPY

In addition to other nursing assessments, the patient receiving CSI should have the following assessment parameters evaluated before therapy is initiated:

• Verify physician’s order for patient’s name, drug name, type of medication, dosage, and route of administration against the medication administration record (MAR).

• Collect drug information necessary to administer drug safely, including action, purpose, side effects, safe dosage range, and nursing implications. Verify that medication can be given through this route.

• Assess the patient’s medical history, drug allergies, and medication history.

• Assess for factors that may contraindicate CSI, such as circulatory shock, reduced local tissue perfusion, or pulmonary congestion.

• Assess adequacy of the patient’s subcutaneous tissue and skin condition to determine appropriate site.

• Assess patient/family knowledge regarding medication to be received and readiness to learn self-administration.

• Assess the patient’s symptoms before initiating the medication therapy. (N ote: When administering analgesia, assess the patient’s level of pain using the appropriate pain scale [Perry and Potter, 2006].) The advanced practice nurse, physician, or pharmacist determines drug dose based on the amount of pain medication the patient used in 24 hours. An equianalgesic chart is used to convert IV, IM, and oral medication doses to CSI doses (Pasero, 2002).

• Check the compatibility of any medications combined in the infusions.

INITIATION OF CONTINUOUS SUBCUTANEOUS INFUSION

Site Selection

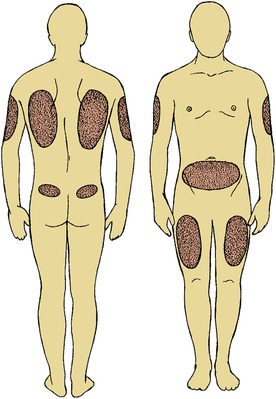

Before initiation of therapy, carefully assess the patient’s skin condition and the adequacy of subcutaneous tissue stores. Anatomical sites used for subcutaneous injections and the upper chest may be used for CSI (Perry and Potter, 2006). The anterior thigh is more commonly used for subcutaneous injection and the outer thigh area is more commonly used for CSI (Figure 26-1).

|

| FIGURE 26-1 Common sites for subcutaneous injections. (From Potter PA, Perry AG: Basic nursing: essentials for practice, ed 6, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.) |

Site selection will depend on the patient’s activity level, subcutaneous tissue stores, and the type of medication required. For example, pain medications delivered to ambulatory patients are best delivered in the upper chest (infraclavicular area) to allow maximum mobility (Perry and Potter, 2006). In the confused patient, the posterior scapula area may inhibit the patient from pulling at the site (Anderson and Shreve, 2004). Insulin is absorbed most consistently in the abdomen; thus a site in the abdomen away from the belt line is preferred for a continuous insulin infusion (Perry and Potter, 2006). Generally, sites should be located away from the waistline, areas of constriction from clothing, and areas of large underlying muscles or nerves. Avoid bony prominences, irritated or infected sites, and sites around tumors, deep creases, recently radiated areas, and other skin lesions. CSI is not contraindicated for cachectic patients (Pasero, 2002); however, available sites may be limited. The upper abdomen is a recommended site for patients with limited peripheral subcutaneous tissue (Perry and Potter, 2006). Some sources recommend avoiding the chest wall to prevent iatrogenic lung puncture during needle insertion (Weissman, 2005).

Equipment/Supplies

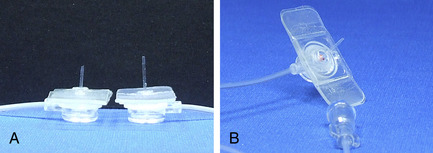

Gather all equipment and supplies before initiating the infusion. An electronic infusion device (EID) is required for all medication infusions. The EID must have a lock-out interval feature, bolus dosing options, and appropriate clinical safety alarms. For subcutaneous infusions of isotonic fluids, an EID or add-on flow regulator may be used to control the fluid infusion rate. Other general supplies include aseptic nonsterile gloves, administration sets, transparent semipermeable membrane (TSM) dressings, tape, gauze pads, alcohol wipes, skin disinfectants, and a subcutaneous access device (e.g., over-the-needle catheter or prepackaged subcutaneous set) (Figure 26-2). Commercially prepared start kits contain the basic supplies; however, a tourniquet is not needed since venipuncture is not required.

|

| FIGURE 26-2 A, Medtronic standard and micro catheter. B, Medtronic Sof-Set. (From Applied Medical Technology, Cambridge, United Kingdom.) |

Patient preparation

After the orders from an authorized prescriber are verified, the equipment and supplies are assembled, and the patient is properly identified following organizational guidelines. Care is taken to provide privacy and to explain all procedures and rationales to the patient and/or family. Educational materials are provided, if applicable, and time is allowed for questions and answers. Ensure the patient’s readiness by assisting the patient to a position of comfort. If initiating an opioid infusion for pain management, assess the patient’s pain rating before starting the subcutaneous infusion.

Site preparation

According to the Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice “Aseptic technique shall be used and standard precautions shall be observed for subcutaneous access.” (INS, 2006a) Hand hygiene is performed before and after all patient care contact. Site preparation for CSI is done in the same manner as for venipuncture. If the skin is visibly soiled, wash the selected site with soap and water before applying skin disinfectants and follow organizational guidelines for site preparation. Excess hair may be clipped with scissors or removed with single-use surgical clippers that have disposable clipper heads.

Device selection

Currently, there are three device options for accessing subcutaneous tissue for infusion of medications or isotonic fluids: (1) stainless steel winged needles, (2) over-the-needle catheters, and (3) subcutaneous infusion sets (e.g., Sof-set, Sub-Q-Set). Traditionally, stainless-steel winged needles have been used to obtain subcutaneous access for infusion. However, these devices are intended for short-term duration IV infusions, usually 1 to 4 hours, or a single dose of medication. Over-the-needle catheters (e.g., VialonTM, Teflon®) have been used with reports of increased patient comfort, and decreased risk of tissue damage to the patient or inadvertent needlestick injury to the health care provider. A small gauge over-the-needle catheter (usually 24 gauge) can provide safe and comfortable access into the subcutaneous tissue.

Currently, prepackaged subcutaneous access devices are commercially available with a 90-degree angle needle or a 90-degree angle over-the-needle catheter. These devices are made in a 6- or 9-mm length for optimal access to the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 26-3). A special infusion set is now available exclusively for hypodermoclysis. The Aqua-C Hydration system (Norfolk Medical, Skokie, Ill) combines infusion tubing with an integrated flow regulator spiked into a solution container. The access device is called a “clysis strip” and has two 25- or 27-gauge, 6-mm-long needles placed 1.5 inches apart on an adhesive vinyl strip attached to the end of the tubing (Figure 26-4) (Walsh, 2005).

|

| FIGURE 26-3 Sub-Q-Set. (Courtesy Baxter International, Inc., Deerfield, Ill.) |

|

| FIGURE 26-4 The Aqua-C Hydration set. (Courtesy Norfolk Medical Products Inc., Skokie, Ill.) |

The needle design allows two sites to be accessed with one device and minimizes the risk of improper needle placement. Using the Aqua-C Hydration system, the maximum infusion rate can be achieved with a single administration setup. The use of a specialized set for hypodermoclysis may also decrease the possibility of mistaking the subcutaneous infusion for an intravenous infusion (Walsh, 2005). According to the Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice (2006a), the selected continuous subcutaneous access device should be of the smallest gauge and shortest length necessary to establish subcutaneous access. The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, 1999) reports that hollow-bore needles incur the greatest risks of needlestick injuries to health care workers. Of nearly 5000 percutaneous injuries reported by hospitals participating in CDC studies between June 1995 and July 1999, 62% were associated with hollow-bore needles, primarily hypodermic needles attached to syringes (29%) and winged-steel needles (13%). Data from these studies showed that approximately 38% of injuries occur during use and 42% occur after use and before disposal (NIOSH, 1999). Recommendations for avoiding potential needlestick injuries include eliminating unnecessary use of needles, using devices with safety features, and promoting education and safe work practices for handling needles and related systems (NIOSH, 1999).

Device placement

Insert the subcutaneous device according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Over-the-needle catheters are placed into the subcutaneous tissue at approximately a 30- to 45-degree angle depending on the thickness of the subcutaneous tissue. Prepackaged subcutaneous access devices are inserted at a 90-degree angle. These devices are manufactured at specific lengths to optimize access to the subcutaneous tissue, depending on the thickness of the subcutaneous layer.

Device securement and dressing

Subcutaneous access devices are secured with tape and transparent semipermeable membrane (TSM) dressings to allow for site observation and palpation. The administration set and/or pump should be clearly labeled “Subcutaneous Infusion” to prevent the possibility of mistaking the infusion for an intravenous line. Preprinted manufactured labels are available to identify subcutaneous infusions.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access