The Child with a Musculoskeletal Condition

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

4. Describe the management of soft tissue injuries.

5. Discuss the types of fractures commonly seen in children and their effect on growth and development.

6. Differentiate between Buck’s extension and Russell traction.

7. Compile a nursing care plan for the child who is immobilized by traction.

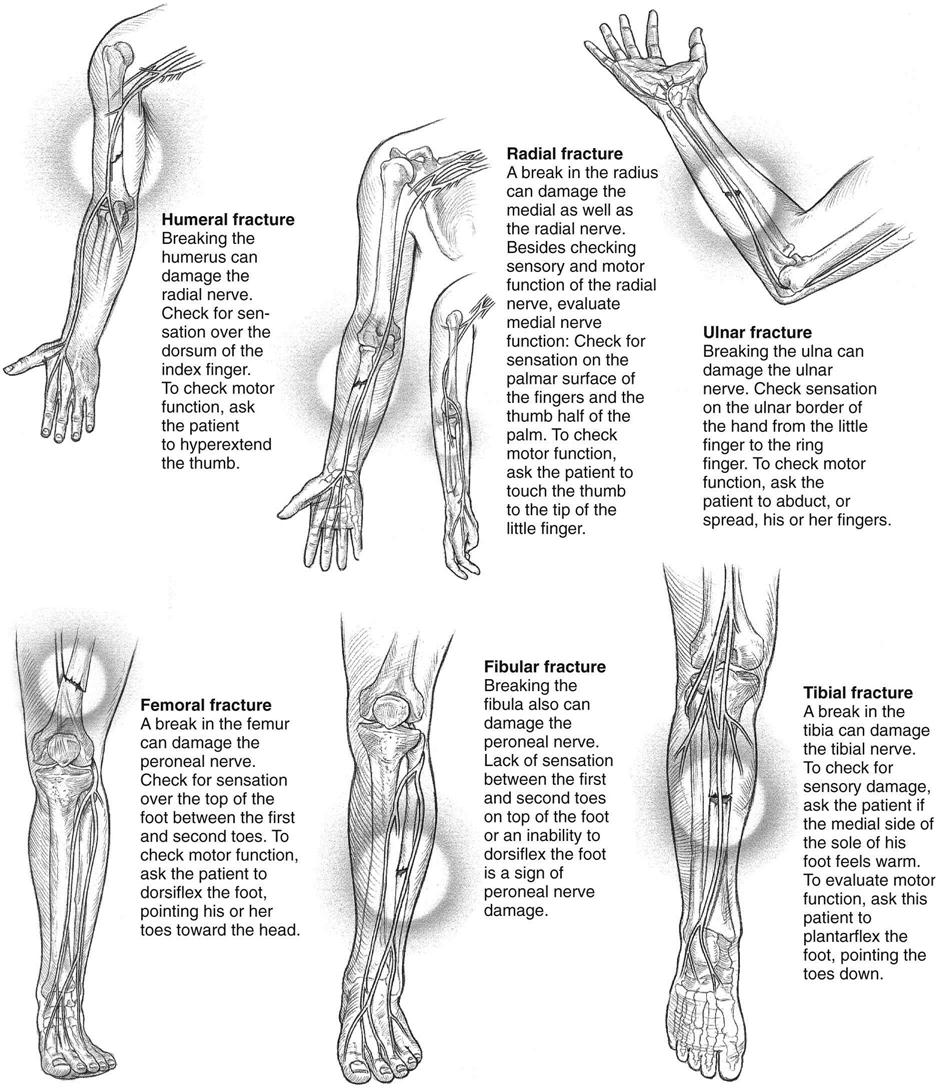

8. Describe a neurovascular check.

9. Discuss the nursing care of a child in a cast.

10. List two symptoms of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy.

11. Describe the symptoms, treatment, and nursing care for the child with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

14. Identify symptoms of abuse and neglect in children.

15. Describe three types of child abuse.

16. State two cultural or medical practices that may be misinterpreted as child abuse.

Key Terms

arthroscopy (p. 563)

Bryant’s traction (p. 564)

Buck’s extension (p. 564)

compartment syndrome (p. 568)

compound fracture (p. 564)

contusion (kŏn-TŪ-zhŭn, p. 563)

epiphysis (ĕ-PĬF-ă-sĭs, p. 564)

gait (p. 562)

genu valgum (JĒ-nū VĂL-găm, p. 563)

genu varum (JĒ-nū VĂR-ăm, p. 563)

greenstick fracture (p. 564)

hematoma (hē-mă-TŌ-mă, p. 563)

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (p. 573)

Milwaukee brace (p. 575)

neurovascular checks (p. 568)

osteomyelitis (p. 571)

Russell traction (p. 564)

shin splints (p. 577)

slipped femoral capital epiphysis (p. 572)

spiral fracture (p. 564)

sprain (p. 563)

strain (p. 563)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

The musculoskeletal system supports the body and provides for movement. The muscular and skeletal systems work together to enable a person to sit, stand, walk, and remain upright. In addition, muscles move air into and out of the lungs, blood through vessels, and food through the digestive tract. They also produce heat, which aids in numerous body chemical reactions. Bones act as levers and provide support. Red blood cells are produced in the bone marrow, and minerals such as calcium and phosphorus are also stored there.

The musculoskeletal system arises from the mesoderm in the embryo. A great portion of skeletal growth occurs between the fourth and eighth weeks of fetal life. As the limbs elongate before birth, muscle masses form in the extremities. The Ballard scoring system (see Figure 13-2) is one measure of assessing neuromuscular maturity at birth. Testing various reflexes is another.

Locomotion develops gradually and in an orderly manner in the growing child. A marked deceleration of growth is always a signal for investigation.

Musculoskeletal System: Differences Between the Child and the Adult

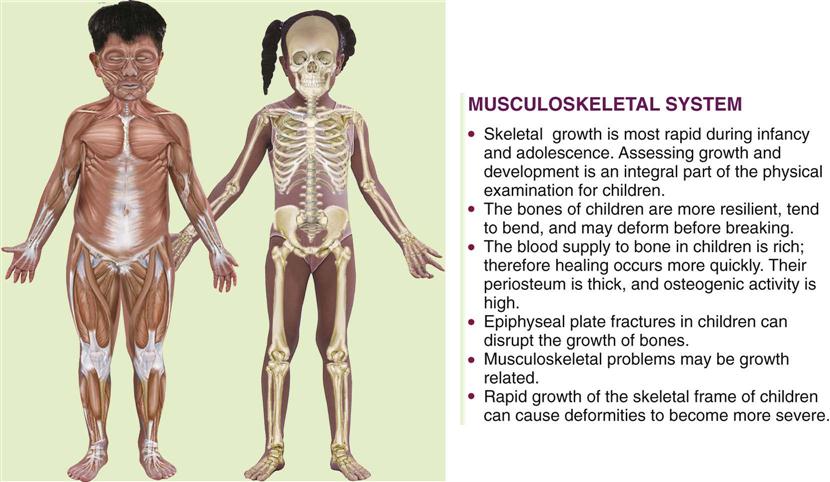

The pediatric skeletal system differs from the adult skeletal system in that bone is not completely ossified, epiphyses are present, and the periosteum is thicker and produces callus more rapidly than in the adult. The lower mineral content of the child’s bone and its greater porosity increase the bone’s strength. However, rotational or angular forces can stress ligaments that insert at the epiphyseal area of the bone, and injury to the epiphysis can affect bone growth. Because of the presence of the epiphysis and hyperemia caused by the trauma, bone overgrowth is common in healing fractures of children under 10 years of age. Figure 24-1 describes some differences between the child’s and adult’s skeletal and muscular systems.

Observation and Assessment of the Musculoskeletal System in the Growing Child

To assess the musculoskeletal system of the growing child and to identify deviations, the nurse must have a basic understanding of the effect of growth, neurological development, and motor milestones at various ages. The newborn hip has limited internal rotation range of motion (ROM). The legs are maintained in a flexed position, and the lower leg has an internal rotation (internal tibial torsion) caused by the effects of uterine positioning; this can last 4 to 6 months. The general curvature of the newborn spine is a C shape from the thoracic to the pelvic level; it changes with the mastery of motor skills to a double S curve in childhood (see Figure 17-1). The newborn’s feet normally turn inward (varus) or outward (valgus), but the turning-in self-corrects when the sole of the foot is stroked. The toddler’s feet appear flat because of the presence of a fat pad at the arch. Any delay in neurological development can cause a delay in the mastery of motor skills, which can result in altered skeletal growth.

Assessment of the musculoskeletal system includes observation, palpation, ROM, and gait assessment in children who can walk. Children who do not walk independently by 18 months of age have a serious delay and should be referred to a health care provider for follow-up.

Observation of Gait

A gait is a characteristic manner of walking. The toddler who begins to walk has a wide, unstable gait. The arms do not swing with the walking motion. By 18 months of age the wide base narrows and the walk is more stable. By 4 years of age the child can hop on one foot, and arm swings occur with walking. By 6 years of age the gait resembles the adult walk with equal stride lengths and associated arm swing. The trunk is centered over the legs, and movement is symmetrical. When a child favors one side, pain may be present. Toe walking after 3 years of age can indicate a muscle problem.

In most cases, excessive in-toeing, or pointing of the toe inward, will resolve by 4 years of age. These children trip and fall easily. Teaching proper sitting and body mechanics is the treatment of choice. Participation in ballet classes and in-line skating will enhance hip flexibility. If the problem does not resolve, a brace may be prescribed. Failure to treat can result in hip, knee, or back problems in adulthood.

Young children appear bowlegged (genu varum) or knock-kneed (genu valgum), with the knees turned inward until 5 years of age. Bowing is seldom pathological. The ligaments that support the arch are not mature before 6 years of age, and therefore the child may appear to have flat feet. If the condition interferes with walking, an orthotic appliance can be prescribed for the child to wear inside the shoes. When the flat foot is painful, a referral for follow-up examination should be initiated. The role of the nurse is to reassure parents that unless there is associated pain or a problem with motor or nerve functions, many minor abnormal-appearing alignments will spontaneously resolve with activity.

Observation of Muscle Tone

The nurse should assess symmetry of movement and the strength and contour of the body and extremities. The strength of the extremities can be tested by having the child push away the examiner’s hand with his or her foot or hand.

Neurological Examination

A neurological assessment is a vital part of a comprehensive musculoskeletal examination. An assessment of reflexes, a sensory assessment, and the presence or absence of spasms should be noted.

Diagnostic Tests and Treatments

Radiographic Studies

Radiographs (x-ray films) are taken to confirm a suspected pathological condition, and the affected area is compared with the unaffected area.

Bone Scans.

Bone scans are helpful in identifying pathological conditions that may not clearly be seen on a routine x-ray study, such as septic arthritis or tumors.

Computed Tomography.

Computed tomography (CT) provides a cross-sectional picture of the bone and its relationship to other structures within the area of examination.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not involve harmful radiation. MRIs produce detailed pictures of the brain, spinal cord, and soft tissue lesions, including a slipped femoral epiphysis.

Ultrasound.

Ultrasound does not involve harmful radiation. It is used to rule out foreign bodies in soft tissues, joint effusions, and developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Laboratory Tests and Treatments

A complete blood count (CBC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may rule out septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B-27 may help diagnose rheumatological disorders.

A thorough history is necessary to determine the basis for musculoskeletal problems, which are often insidious. The nurse determines the history of the injury; the location of pain; when symptoms started; any weakness, numbness, or loss of function in an extremity; and whether the problem is affecting the daily activities of the child. An arthroscopy is commonly performed on adolescents with sports injuries. The physician is able to look inside the joint (usually the knee or shoulder) to determine the extent of injury. The area is inspected, foreign particles are removed, or repairs are made to the torn menisci. A bone biopsy may reveal a malignancy. Muscle biopsy may detect muscular dystrophy.

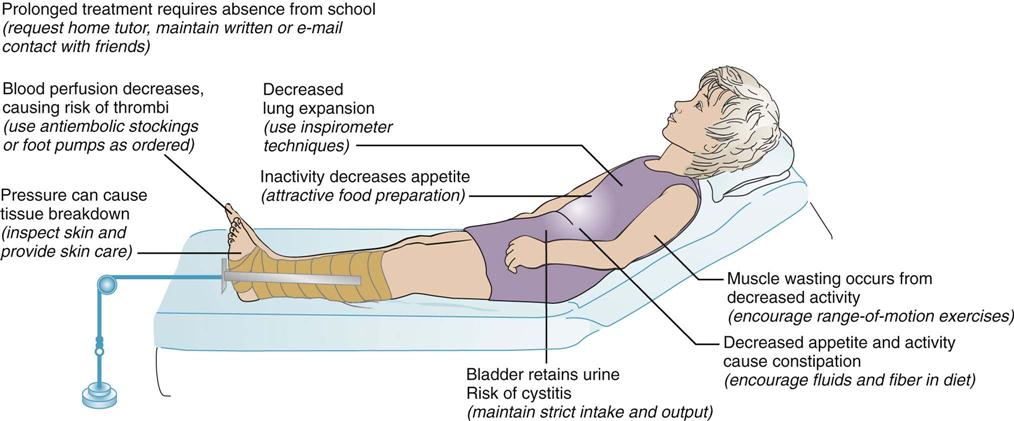

Traction, casting, and splints are used in accordance with the patient’s needs. Three types of skin traction are often used for the lower extremities of children: Bryant’s traction, Buck’s extension, and Russell traction. Children with musculoskeletal disorders may require lengthy hospitalization. Immobility causes a deceleration in body metabolism. Nursing interventions focus on maintaining body functions. ROM exercises and the use of a trapeze prevent muscle atrophy. Foods high in roughage stimulate the digestive tract and prevent constipation. Respiratory exercises prevent pneumonia. These and other measures can prevent complications that can lengthen hospitalization for the child. (Clubfoot and congenital hip dysplasia are discussed in Chapter 14. Rickets is discussed in Chapter 28.)

Pediatric Trauma

Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue injuries usually accompany traumatic fractures in the child at play or the adolescent involved in sports activities and include the following:

• Strain: A microscopic tear to the muscle or tendon occurs over time and results in edema and pain.

Treatment of Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue injuries should be treated immediately to limit damage from edema and bleeding. A cold pack and elastic wrap will reduce edema and bleeding and relieve pain, and should be applied at alternating 30-minute intervals. (After a 30-minute period, ischemia can occur and impede the tissue perfusion.) Elevating the extremity above heart level reduces edema. When an elastic bandage is used for compression, a priority nursing responsibility is to perform frequent neurovascular checks to ensure adequate tissue perfusion.

Prevention of Pediatric Trauma

Accidents are common in childhood, but much can be done to prevent morbidity and mortality. Parents are responsible for maintaining a safe environment for their children. Nurses are responsible for educating parents and schoolteachers about how to prevent accidental injury and maintain a safe environment.

The proper use of pedestrian safety practices, car seat restraints, bicycle helmets and other athletic protective gear, pool fences, window bars, deadbolt locks, and locks on cabinets can prevent many injuries to children. Pediatric trauma can cause permanent disability or premature death. Nursing assessment and interventions can assist the injured child toward recovery. The nurse also has a community responsibility to support legislation that would maintain safe environments for children.

Traumatic Fractures

Pathophysiology.

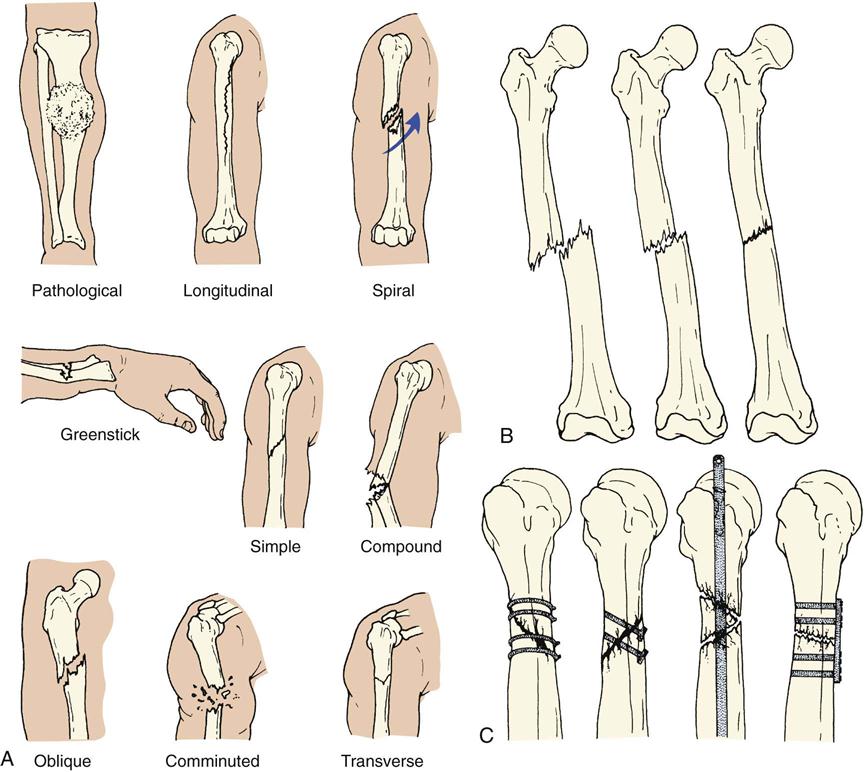

A fracture is a break in a bone and is mainly caused by accidents. It is characterized by pain, tenderness on movement, and swelling. Discoloration, limited movement, and numbness may also occur. In a simple fracture the bone is broken, but the skin over the area is not. In a compound fracture a wound in the skin accompanies the broken bone, and there is an added danger of infection. A greenstick fracture is an incomplete fracture in which one side of the bone is broken and the other is bent. This type of fracture is common in children because their bones are soft, flexible, and more likely to splinter. In a complete fracture the bone is entirely broken across its width. Figure 24-2 illustrates various types of fractures. When an x-ray film reveals multiple fractures in various stages of healing, child abuse should be suspected.

A fracture heals more rapidly in a child than it does in an adult. The child’s periosteum is stronger and thicker, and there is less stiffness on mobilization. Injury to the cartilaginous epiphysis, which is found at the ends of the long bones, is serious if it happens during childhood because it may interfere with longitudinal growth. Care of a child in a cast is discussed in Chapter 14. Casts may be made of plaster or fiberglass.

Fractures of the Femur in Early Childhood.

The femur (the thigh bone) is the largest and strongest bone of the body. It is one of the most prevalent serious breaks that occur during early childhood. A spiral fracture of the femur is caused by a forceful twisting motion. When the history of an injury does not correlate with x-ray findings, child abuse should be suspected because spiral fractures can be the result of manual twisting of the extremity. The child complains of pain and tenderness when the leg is moved and cannot bear weight on it. Clothes are gently removed, starting at the uninjured side and proceeding to the injured side. It may be necessary to cut the clothes; x-ray films confirm the diagnosis. Skin traction is used to reduce the fracture and keep the bones in proper alignment.

Treatment of Fractures with Traction

Traction in the Younger Child.

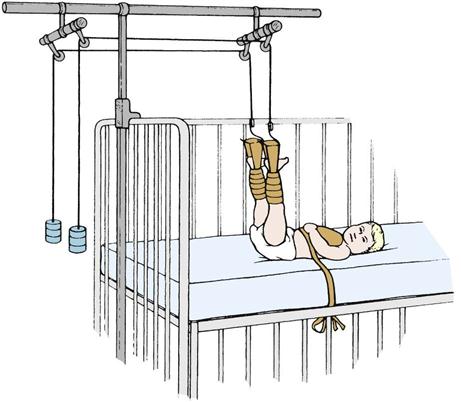

Bryant’s traction is used for treating fractures of the femur in children under 2 years of age or under 20 to 30 lb. Weights and pulleys extend the limb as in the Buck’s extension; however, the legs are suspended vertically (Figure 24-3). The weight of the child supplies the countertraction.

Traction in the Older Child.

Traction is used when the cast cannot maintain alignment of the two bone fragments. Skeletal muscles act as a splint for the fracture. Traction aligns the injured bone by the use of weights and countertraction. Immobilization is maintained until the bones fuse.

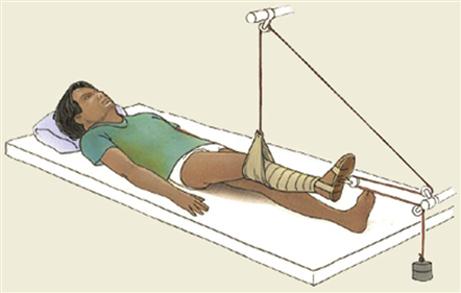

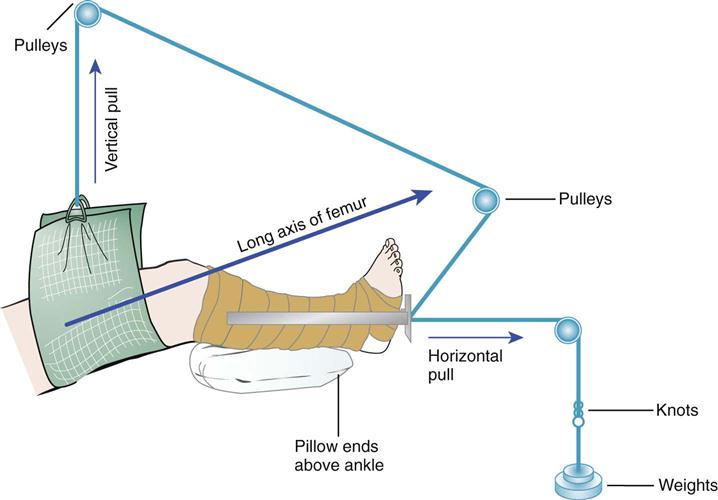

Buck skin traction (Buck’s extension) is a type of skin traction used in fractures of the femur and in hip and knee contractures. It pulls the hip and leg into extension. Countertraction is supplied by the child’s body; therefore it is essential that the child not slip down in bed and that the bed not be placed in high-Fowler’s position. Buck’s extension is sometimes used preoperatively, either unilaterally or bilaterally, to reduce pain and muscle spasm associated with a slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Russell traction is similar to Buck’s extension. In Russell traction, however, a sling is positioned under the knee, which suspends the distal thigh above the bed (Figure 24-4). Skin traction is applied to the lower extremity. Pull is in two directions, vertically from the knee sling and longitudinally from the foot plate (Figure 24-5). This prevents posterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur, which can occur in children in traction. Split Russell traction uses two sets of weights, one suspending the thigh and the other exerting a pull on the leg, with weights at the head and foot of the bed. Balanced suspension using the Thomas splint and Pearson attachments is used to treat diseases of the hip as well as fractures in older children and adolescents. It may be used both before and after surgery.

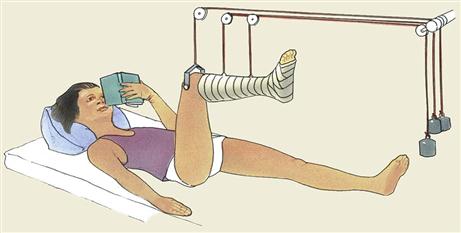

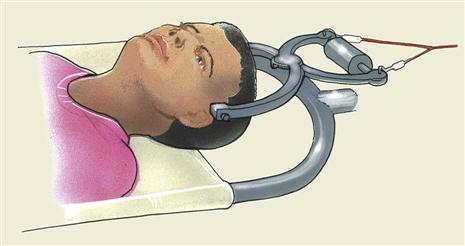

In skeletal traction a Steinmann pin or Kirschner wire is inserted into the bone, and traction is applied to the pin. Daily care of the pin site is essential. “Ninety-ninety” (or ninety degree–ninety degree) traction with a boot cast or sling on the lower leg may be used (Figure 24-6). Crutchfield, or Barton, tongs may be used in the skull to provide cervical traction (Figure 24-7). Skeletal traction carries the added risk of infection from skin bacteria that may cause osteomyelitis. The child in traction experiences certain effects as a result of immobilization (Figure 24-8). Visitors are important to the child in traction, and a school tutor should be contacted so that the child will be able to return to class after healing occurs.

Nursing Responsibilities for Traction.

The nurse observes the traction ropes to be sure they are intact and in the wheel grooves of the pulleys and that the child’s body is in good position. In Bryant’s traction, the legs should be at right angles to the body, with the buttocks raised sufficiently to clear the bed. In all types of traction, elastic bandages should be neither too loose nor too tight. A jacket restraint may be used to keep the child from turning from side to side. The weights are not removed once applied. Continuous traction is necessary. The weights must hang free, and the pull of the weights must not be obstructed by room furnishings, such as a chair. The weights are not lifted or supported when the bed is moved.

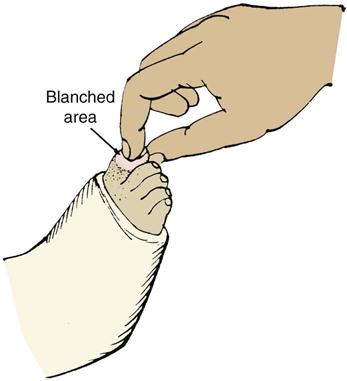

The nurse performs frequent neurovascular checks to the toes to see that they are warm and that their color is good (Figure 24-9). Observations such as cyanosis, numbness, or irritation from attachments; tight bandages; severe pain; or the absence of pulse rates in the extremities are reported immediately to the nurse in charge. A specific and serious complication of any traction is Volkmann’s ischemia (ischein, “to hold back,” and haima, “blood”), which occurs when the circulation is obstructed. When the legs are elevated overhead, as in Bryant’s traction, there is gravitational vascular drainage. Arterial occlusion can cause anoxia of the muscles and reflex vasospasm, which when unnoticed could result in contractures and paralysis.

The child is bathed, and back and buttock care is given. A sheepskin padding may also be used. The sheets are pulled taut and are kept free of crumbs. The jacket restraint is changed when it is soiled. The child is encouraged to drink plenty of fluids and to eat foods that are high in roughage to prevent constipation caused by a lack of exercise. Because the child in traction is unable to sit upright when eating, special precautions to prevent choking and aspiration during mealtime are a priority nursing responsibility. Stool softeners may be necessary. A fracture pan is used for bowel movements, and a careful record is kept of eliminations. Deep-breathing exercises are encouraged to prevent the collection of fluid in the lungs caused by the child’s immobility. These exercises may be done by blowing bubbles or blowing a pinwheel.

Diversional therapy is important because hospitalization may be lengthy. Toys may be securely suspended over the child’s head so they are within easy reach. The child’s crib is taken to the playroom when possible so the child can experience the excitement of the activities there.

DVDs, CDs, MP3 players, video games, stories, and other forms of entertainment are important aspects of a total nursing care plan. Pain control is essential. Parents are encouraged to visit the child as often as possible. With proper treatment the prognosis for the child with this condition is good.

Neurovascular checks.

A priority nursing responsibility in the care of a child with a fracture who is in traction or has a cast or Ace bandage in place is to perform neurovascular assessments or neurovascular checks at regular intervals (Skill 24-1).

Nursing Care Plan 24-1 describes interventions for the child in traction.