The Child with a Sensory or Neurological Condition

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Discuss the prevention and treatment of ear infections.

3. Outline the nursing approach to serving the hearing-impaired child.

4. Discuss the cause and treatment of amblyopia.

5. Compare the treatment of paralytic and nonparalytic strabismus.

6. Review the prevention of eyestrain in children.

7. Discuss the functions of the 12 cranial nerves and nursing interventions for dysfunction.

8. Describe the components of a “neurological check.”

9. Outline the prevention, treatment, and nursing care for the child with Reye’s syndrome.

10. Describe the symptoms of meningitis in a child.

11. Describe three types of posturing that may indicate brain damage.

12. Discuss the various types of seizures and the relevant nursing responsibilities.

13. Prepare a plan for success in the care of a mentally retarded child.

14. Describe four types of cerebral palsy and the nursing goals involved in care.

15. State a method of determining level of consciousness in an infant.

16. Describe signs of increased intracranial pressure in a child.

17. Discuss neurological monitoring of infants and children.

18. Identify the priority goals in the care of a child who experienced near-drowning.

19. Formulate a nursing care plan for the child with a decreased level of consciousness.

Key Terms

amblyopia ( ăm-blē-Ō-pē-ă, p. 535)

athetosis (ăth-ĕ-TŌ-sĭs, p. 548)

aura (ĂW-ră, p. 544)

barotrauma (p. 534)

clonic movement (p. 543)

cognitive impairment (p. 551)

concussion (p. 553)

conjunctivitis (p. 536)

dyslexia (p. 535)

encephalopathy (ĕn-sĕf-ă-LŎP-ă-thē, p. 539)

enucleation (ē-nū-klē-Ā-shŭn, p. 537)

epicanthal folds (p. 535)

extensor posturing (p. 554)

flexor posturing (p. 554)

generalized seizures (p. 544)

grand mal (p. 544)

hyperopia (hī-pŭr-Ō-pē, p. 536)

idiopathic (ĭd-ē-ō-PĂTH-ĭk, p. 544)

increased intracranial pressure (ICP) (p. 540)

ketogenic diet (p. 546)

mental retardation (p. 551)

myringotomy (mĭr-ĭng-GŎT-ŏ-mē, p. 532)

neurological check (p. 538)

nystagmus (nĭs-TĂG-mŭs, p. 543)

opisthotonos (ō-pĭs-THŎT-ō-nŏs, p. 541)

papilledema (păp-ĭl-ă-DĒ-mă, p. 543)

paroxysmal (păr-ŏk-SĭZ-mŭl, p. 544)

partial seizures (p. 544)

petit mal (p. 544)

postictal lethargy (pōst-ĬK-tăl, p. 544)

posturing (p. 554)

sepsis (SĔP-sĭs, p. 540)

shaken baby syndrome (p. 554)

sign language (p. 533)

status epilepticus (p. 547)

strabismus (stră-BĬZ-mŭs, p. 536)

tonic movement (p. 543)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

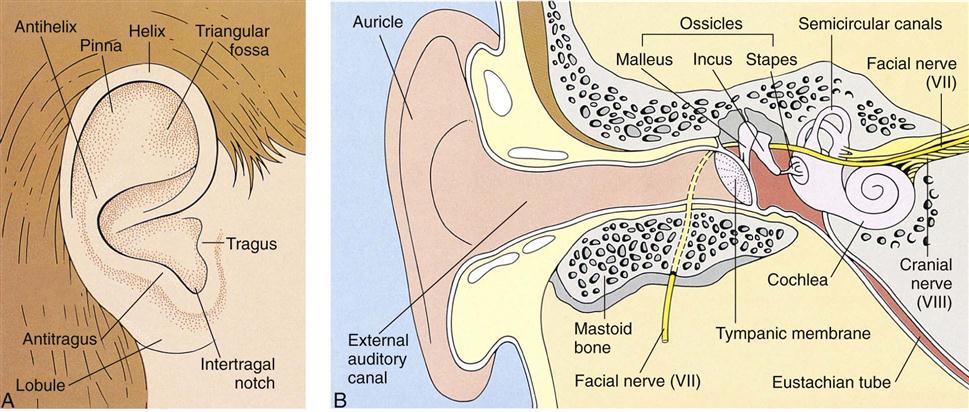

The Ears

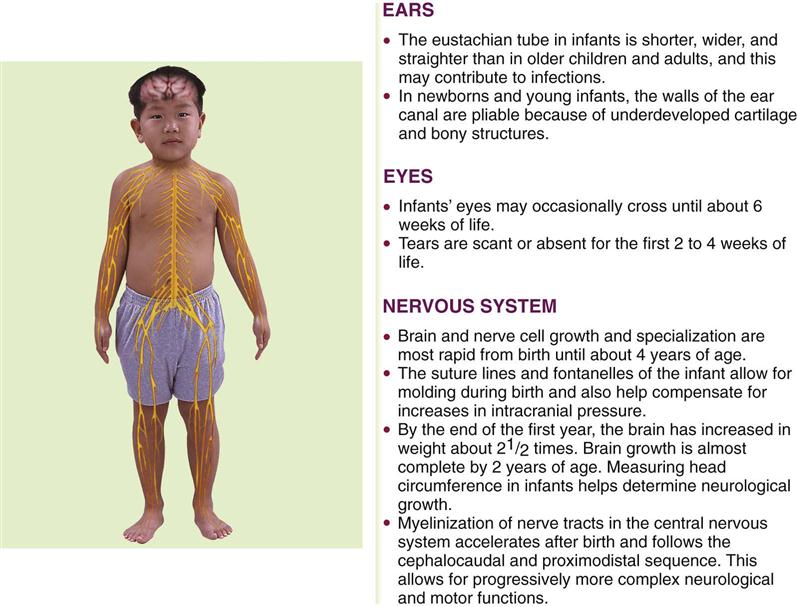

The ear, which can be considered a part of the nervous system, contains the receptors of the eighth cranial (acoustic) nerve. The ear performs two main functions: hearing and balance. Figure 23-1 summarizes ear, eye, and neurological differences between children and adults. The three divisions of the ear are the external ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear (Figure 23-2). In the newborn the tympanic membrane is almost horizontal and is more vascular than in the adult. It has a dull and opaque appearance and an inconsistent light reflex. The eustachian tube is shorter and straighter in the infant than in the adult. Three functions of the eustachian tube are ventilation of the middle ear, protection from nasopharyngeal secretions and sound pressure, and drainage. Middle-ear infections are common during early childhood.

When nurses examine the ear, they observe both the exterior and the interior. Ear alignment is observed. The top of the ear should cross an imaginary line drawn from the outer canthus of the eye to the occiput (see Figure 12-6). Low-set ears may be associated with kidney disorders and mental retardation. The outer ear and the area around it are inspected for cleanliness and drainage. The inner ear is examined with an otoscope. One method of restraint used when assisting with the examination of the inner ear is to lay the child on a table with the arms held alongside the head, which is turned to the side. Another method of positioning a child for an ear examination is placing the child in the lap of the adult (see Figure 22-5).

Disorders and Dysfunction of the Ear

Otitis Externa

An acute infection of the external ear canal is called otitis externa and is often referred to as swimmer’s ear because prolonged exposure to moisture is often the precipitating factor. Pain and tenderness on manipulating the pinna or tragus of the ear are specific signs of this type of infection. The ear canal may be erythematous, but the tympanic membrane is normal. A foreign body, cellulitis, diabetes mellitus, and herpes zoster should be ruled out. Irrigation and topical antibiotics or antivirals are the treatment of choice. The health care provider may insert a loose cotton gauze (wick) into the outer third of the ear canal. The wick is kept moist with frequent drops of the appropriate medicated solution.

Acute Otitis Media

Pathophysiology.

Otitis media (ot, “ear,” itis, “inflammation of,” and media, “middle”) is an inflammation of the middle ear. The middle ear is a tiny cavity in the temporal bone. Its entrance is guarded by the sensitive tympanic membrane, or eardrum, which transmits sound waves through the “oval window” to the inner ear, which contains the organs of hearing and balance. The middle ear opens into air spaces, or sinuses, in the mastoid process of the temporal bone. It is also connected to the throat by a channel called the eustachian tube. These structures—the mastoid sinuses, the middle ear, and the eustachian tube—are lined by mucous membranes. As a result, an infection of the throat can easily spread to the middle ear and lead to mastoiditis. The eustachian tube also protects the middle ear from nasopharyngeal secretions, provides drainage of middle ear secretions into the nasopharynx, and equalizes air pressure between the middle ear and the outside atmosphere. These protective functions are diminished when the tubes are blocked. Unequalized air pressure within the ear creates a negative pressure that allows organisms to be swept up into the eustachian tube.

Otitis media (OM) occurs most often after an upper respiratory tract infection and usually affects children between 6 and 24 months of age and in early childhood. It is caused by various organisms, of which Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae are the most common. Polyvalent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines have reduced the incidence of pneumococcal otitis media, but these vaccines are not effective in children under 2 years of age because they are not capable of producing an antibody response.

Infants are more prone to middle ear infections than older children and adults because their eustachian tubes are shorter, wider, and straighter. When infants lie flat for long periods, microorganisms have easy access from the eustachian tube to the middle ear. Feeding methods may have a bearing on middle ear infection, for instance, the pooling of fluids such as milk in the throat of an infant who falls asleep with a bottle of milk provides a source for growth of organisms. The infant’s humoral (humor, “body fluid”) defense mechanisms are immature. Children in passive smoking environments have more respiratory infections because of the effect of secondary smoke on the protective cilia that line the nose. Day care attendance can contribute to the risk of upper respiratory infections and OM because of increased exposure to ill children. Upper respiratory infections are discussed in detail in Chapter 25.

Manifestations.

The symptoms of OM are pain in the ear, which is often very severe; irritability; and diminished hearing. Fever, which may be as high as 40° C (104° F), headache, vomiting, diarrhea, and febrile seizures may also occur. Earaches in infants may be manifested by general irritability, frequent rubbing or pulling at the ear, and rolling of the head from side to side. The older child can point to the place that is tender. Visualization of the tympanic membrane via otoscope reveals a reddened and bulging membrane.

If an abscess forms, a rupture of the eardrum may result, and drainage from the ear may be evident. When this happens, the pressure is relieved and the child is more comfortable. Some amount of hearing loss may result from the rupture. OM is considered chronic if the condition persists for more than 3 months. Recurrent attacks can lead to serious complications. Chronic OM can lead to cholesteatoma (chole, “bile,” steato, “fat,” and oma, “tumor”), a cystlike sac filled with keratin debris. This may occlude the middle ear and erode adjacent ossicle bones, causing hearing loss. This condition is best treated by an otolaryngologist. Complications of repeated attacks of acute OM can include the development of chronic OM with effusion (fluid accumulation). Hearing loss can result. Treatment may be indicated because hearing loss may impair cognitive and language development that can hamper the education and communication abilities in developing children.

Treatment.

When an infection is evident, treatment is directed toward finding the causative organism and relieving the symptoms. A throat culture may be taken to determine the specific organism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be given orally and should be continued until the prescribed amount of medication has been taken. Analgesics are given to relieve pain. Antihistamines and decongestants are not effective in treating acute OM.

Surgical Treatment.

Surgical intervention may be necessary when medical treatment is unsuccessful. The physician may incise the tympanic membrane to relieve pressure and to prevent a tear by spontaneous rupture. This is called a myringotomy (myringa, “eardrum,” and otomy, “incision of”). A tympanic membrane (TM) button or tympanostomy ventilating tube (PE, pressure equalizer) may be inserted. This may fall out spontaneously within 6 to 12 months. In some children, the tubes may have to be reinserted to continue ventilation. Care is taken to avoid getting water in the ears while bathing or showering. All children should be followed up to make sure that the condition is resolved and to evaluate any hearing loss that may have occurred.

Comfort Measures.

Antipyretics may be given to reduce fever, and a warm compress may be applied locally for comfort. If the eardrum has ruptured, the child is placed on the affected side. Cold may also be beneficial. An ice pack may be prescribed to reduce edema and pressure. The skin around the ears must be kept clean and protected from any drainage to prevent tissue breakdown. Parents are instructed not to insert cotton swabs into the ears.

Hearing Impairment

Pathophysiology.

Approximately 1 in 1000 newborns is born with some type of hearing impairment. This number may increase to 2 in 1000 for hearing loss occurring during childhood. Hearing-impaired children present special challenges to the health care team. Hearing loss can affect speech, language, social and emotional development, and behavior, as well as academic achievement. The nurse should have a basic understanding of how to approach and work with a hearing-impaired child.

The inner ear is fully formed during the early months of prenatal life. If an expectant mother contracts German measles or other viral infection during this period, the child may be born with a hearing loss; this is termed congenital deafness. Deafness can also be acquired. Infectious diseases such as measles, mumps, chickenpox, or meningitis can result in various degrees of hearing loss. The common cold, some medications, exposure to loud noise levels, certain allergies, and ear infections may also be responsible. Hearing problems can also be temporary if they are caused by cerumen (wax) accumulation. Some rattles and squeaky toys can emit sounds as loud as 110 decibels. (Sounds above 80 decibels can cause damage.) These types of toys should not be held close to the infant’s ear.

Early diagnosis and treatment of hearing-impaired children is important to prevent adverse physical and mental complications from developing. Members of the health care team concerned with the child who is hearing impaired include the physician, otologist (ear specialist), audiologist, speech therapist, specially trained teacher, social worker, psychologist, school nurse, and members of the child’s family.

The various degrees of hearing loss range from a complete bilateral loss (which affects both ears) to a loss so mild that the problem is never recognized. Hearing loss can result from defects in the transmission of sound to the middle ear, from damage to the auditory nerve or ear structures, or from a mixed hearing loss that involves both a defect in nerve pathways and interference with sound transmission. If hearing loss is complete, the child misses all the pleasures of sound and has difficulty in communication (children learn to talk by imitating what they hear). Behavior problems may arise because these children do not understand verbal directions. They may become aggressive with other children in their attempt to communicate. If they are ridiculed by playmates, personality development will be affected. Unless these children are helped early in life, they may become socially isolated.

Partial bilateral deafness may be responsible for behavior problems and poor progress in school. It is most commonly caused by chronic ear infections, such as OM, or by blockage of the eustachian tube. Children who have hearing losses in one ear are less affected if hearing in the other ear is normal.

Diagnosis and Treatment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a goal of universal detection of hearing impairment in infants before 3 months of age, with interventions started no later than 6 months of age to minimize problems with growth and development (Wolff et al., 2010). The evoked otoacoustic emissions (OAE) test is a preferred method for neonatal testing. The brainstem auditory evoked response (BAER) test records brain wave responses generated by the auditory system. These tests are easily administered to the newborn infant, and many hospitals routinely screen newborns for hearing ability before discharge. Lack of response by the infant to sounds or music or lack of the startle reflex in infants under 4 months of age are the first signs that may alert the parents or nurse to the possibility of hearing impairment. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are primary requisites, regardless of the child’s age. Complete bilateral deafness is usually discovered during infancy. Partial deafness may be unrecognized until the child begins school. Many hearing problems are detected by the school nurse administering standard hearing tests.

Tympanometry measures ear pressure but is difficult to perform adequately on an active infant or small child. A tuning fork is used to evaluate for air conduction (Rinne test) or bone conduction (Weber test). This type of test requires the child to be cooperative and able to communicate what is heard or felt. Diagnosis of hearing loss can be confirmed by visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA), which identifies sensitivity to sounds in young infants.

Many hearing defects are amenable to medical or surgical treatment. Hearing aids can amplify sound waves. Surgically placed cochlear implants are used for some children with nerve damage. Children who suffer a severe loss of hearing need more extensive help from personnel at an auditory training center. These children must begin treatment as soon as the hearing loss is discovered.

Nursing Care.

Various methods are used to bring the child into the world of sound. Lip reading, sign language, writing, visual aids, and amplified sound are but a few examples. The parents are instructed in means of communication that correspond with those used by the teachers.

The nurse must be aware of the symptoms of deafness in the child. Newborns are observed for their response to auditory stimuli. The Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale evaluates the infant’s orientation response to the sound of a voice. The persistence of the Moro reflex beyond 4 months of age may also be an indication of deafness. The infant who makes no verbal attempts by 18 months of age should undergo a complete physical examination. Indifference to sound, behavior problems, or poor school performance may also be signs of deafness. The nurse inquires into the facilities that are available in the community for such a child.

The hearing-impaired child in the hospital needs the same opportunities to communicate as the child who does not have this disability. The nurse smiles when approaching the child. Body language communicates a lot, especially if there is a severe communication problem. The nurse faces the child when speaking and is positioned at eye level with the child. The nurse must ensure that the child sees him or her before touching to avoid startling the child. Sign language is the use of hand signals that correspond to words and assist in communication with a deaf child. Previously developed speech patterns may regress during hospitalization. Visual aids, writing, or drawing can be used to enhance communication.

If a hearing aid is indicated, the child is equipped with one and taught how to use it. Regular checkups ensure that the hearing aid is working properly. A hearing aid is expensive and invaluable to the child. It is put in a safe place when not in use. When the child goes to surgery, it is given to the parents or placed in the hospital safe. The pockets of hospital gowns are checked before the gowns are placed in the laundry.

The National Hearing Center provides information about hearing aids. Hearing aids are designed to fit in the ear, behind the ear, on eyeglass frames, or on the body with wires to the ear. The nurse should check ear hygiene and be sure hairs are not caught on the end of the hearing aid to ensure a proper fit and to minimize noise and whistling problems. Teaching safe battery handling and storage and promoting self-care are important nursing responsibilities.

Home care of the hearing-impaired child should include speech therapy. Flashing lights should be installed in the home to alert the child to doorbells and other sound-based devices.

Telecommunication devices for the deaf (TDD) are available to enable telephone communication. Closed captioning devices for television are available to the child who can read.

The school nurse can help the family nurture socialization skills. Some hearing-impaired children attend special schools for the deaf, and some are mainstreamed into the general school population. Each hearing-impaired child and each family unit should be followed by the multidisciplinary health care team.

Barotrauma

Barotrauma occurs when there is a change in the atmospheric pressure between the internal body systems and the surrounding environment. An example of barotrauma would be the painful obstruction of auditory tubes when in a pressurized cabin of an airplane. Today many children travel with their family via airplanes and may react to a change in altitude and barometric pressure. During airplane descent, children should be encouraged to yawn or chew on gum to promote swallowing. Infants should be bottle-fed juice or water to promote swallowing, which produces autoinflation and relief of symptoms. Systemic decongestants can be taken before air travel and timed so that their peak effectiveness occurs during airplane descent.

Adolescents may participate in recreational underwater diving that can cause barometric pressure stress to the ear and result in severe earaches and other serious problems. Underwater diving should be slow during the descent phase to minimize negative pressure buildup. Sensory hearing loss and vertigo with nausea and vomiting may be early signs of decompression sickness when it occurs during the ascent phase of diving. The diver should be referred for medical care. Upper respiratory infections or tympanic membrane perforation are contraindications to diving because vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and disorientation can occur, with dangerous results.

The Eyes

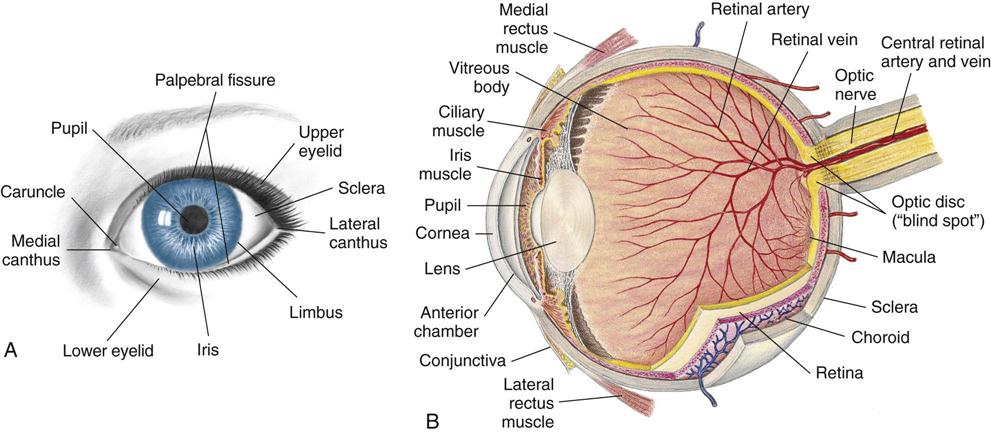

The eye is the organ of vision. The anatomy of the eyeball is depicted in Figure 23-3. The eyes begin to develop as an outgrowth of the forebrain in the 4-week-old embryo. The retinal vessels vascularize (develop) at 40 weeks of gestation, and therefore infants born prematurely often have vision problems throughout their life. At birth, the eye is 65% of adult size. The newborn’s sight is not mature, but the newborn can see. Visual acuity is estimated to be in the range of 20/400. This improves rapidly and may reach 20/40 to 20/30 by 2 or 3 years of age. The shape of the newborn’s eye is less spherical than the adult’s eye. Newborns keep their eyes closed most of the day and can focus and fixate on objects 12 to 30 cm (8 to 12 inches) away for only a few seconds at a time and cannot coordinate or follow without turning their head. By 2 to 4 months infants can move their eyes to follow people or objects. By 4 to 5 months their eyes are open most of the day and the lacrimal glands begin to secrete tears for eye protection. Eye-hand coordination develops. The nurse should document this because the ability to transfer objects from one hand to another is partially dependent on the ability to see the object. The development of the ability to crawl is also partially dependent on the ability to see an object at a distance and attempt to reach it. Depth perception is not developed until 9 months of age. When the child walks or runs, visual depth perception influences the child’s ability to run without falling. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that all children undergo preschool visual screening during well-child visits between 2 and 3 years of age (Kuhn, 2009).

On physical examination the nurse observes the eyes to see if they are symmetrical and are an equal distance from the nose. Epicanthal folds (epi, “upon,” and canthus, “angle”) are folds of skin that extend on either side of the bridge of the nose and cover the inner eye canthus. Some folds are broad and cover a large portion of the inner eye, causing the eye to appear crossed. Large epicanthal folds occur as part of some chromosomal anomalies. Pupils are observed for size, shape, and movement. Their reaction to light is observed by shining a penlight into the eye and quickly removing it. The healthy pupil constricts (gets smaller) as the light approaches and dilates (gets larger) as it disappears (see Figure 23-14). Older children are given explanations concerning the examination. The nurse should assess and document the general appearance of the child as well as achievement of developmental milestones. This includes observing for symmetry of the eye orbit and eyelids, excessive tearing, squeezing of the eyelids, and strabismus (crossed eyes).

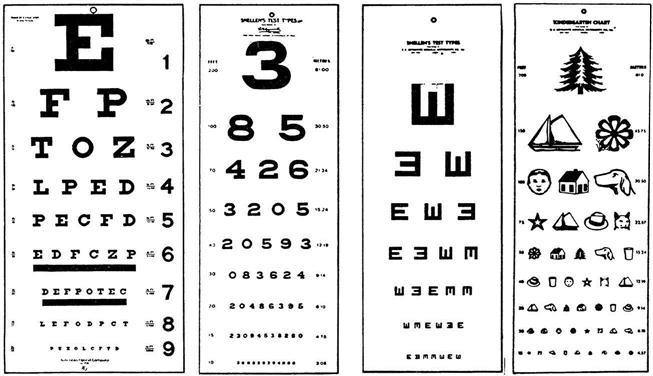

Visual Acuity Tests

The ability of an infant to fixate and focus on an object can be demonstrated by 6 weeks of age. The object should not emit a sound so it is certain the infant is turning toward a sight stimulus rather than a sound stimulus. Visual acuity can be tested by  to 3 years of age.

to 3 years of age.

There are a variety of visual acuity charts (Figure 23-4). The Snellen alphabet chart and the Snellen E version for preschoolers who have not learned the alphabet are commonly used to assess the ability to see near and far objects. Picture cards are also useful for children who do not know letters.

The Titmus machine is often used for school-age children and adolescents. Directions for testing are standardized and must be carefully adhered to for proper results. Computerized tests, such as the random-dot stereogram, are also useful in the visual screening of children. Visual acuity is important in the learning process. Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is discussed in Chapter 13.

Disorders and Dysfunction of the Eye

Dyslexia

Dyslexia (dys “difficult,” and lexis, “diction”) is a reading disability that involves a defect in the cortex of the brain that processes graphic symbols. Although an eye evaluation is recommended when a child has mirror vision or word reversal, the problem does not involve any local eye defect. Correcting vision problems will aid in optimal visual function, but treatment for dyslexia involves remedial instruction.

Amblyopia

Pathophysiology.

Amblyopia (lazy eye) is a reduction in or loss of vision that usually occurs in children who strongly favor one eye. If both retinas do not receive a clearly defined image, bilateral amblyopia may result. However, it is more common for one eye to be affected. When abnormal binocular interaction occurs (such as crossed eyes or strabismus), the prognosis depends on how long the eye has been affected and on the age of the child when treatment begins. The earlier the treatment is given, the better the results. One commonly accepted diagnostic sign is that vision in the normal eye is at least two Snellen lines (E charts) better than that in the affected eye. There are various types of amblyopia. Strabismus is the most common; however, dissimilar refractory errors can also result in this condition. Because amblyopia occurs as a result of sensory deprivation of the affected eye, children are at risk for developing the problem until visual stability occurs, usually by 9 years of age.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

Early detection and prompt treatment are essential. The goal of treatment is to obtain normal and equal vision in each eye. Treatment consists of eyeglasses for significant refractive errors such as hyperopia (farsightedness) or myopia (nearsightedness) and patching (occlusion) of the good eye. The good eye is patched to force the use of the affected eye. Daytime patching may be tried first, since part-time occlusion is sufficient in some cases. Occlusion therapy is often difficult to maintain. The nurse can be of help by explaining the importance of the procedure and by offering support, but the child is often subjected to teasing by peers. Providing a safe place to express feelings is important to promoting a healthy self-image. In most cases an opaque contact lens or a contact lens of sufficiently high power to blur the vision in the better eye is used (Kliegman et al., 2007).

Strabismus

Pathophysiology.

Strabismus (cross-eye), also known as squint, is a condition in which the child is not able to direct both eyes toward the same object. There is a lack of coordination between the eye muscles that direct movement of the eye. When the eyes cannot coordinate sight together, the brain will disable one eye to provide a clear image. The disabled eye can develop permanent visual impairment because of sensory deprivation (amblyopia). Normal binocular vision is the goal and must be accomplished by intervening early before the eye matures.

There are several types of strabismus. Nonparalytic strabismus (concomitant) involves a constant deviation in the gaze related to faulty insertion of the eye muscle. One eye always looks crossed. The extraocular muscles are normal. Paralytic strabismus (nonconcomitant) involves a paralysis or weakness in the extraocular muscle. Double vision is experienced. Deviation of the gaze occurs with movement, when the eye attempts to focus. To prevent double vision (diplopia) the child will tilt his or her head or squint when focusing on an object. Strabismus may be present at birth or may be acquired after a disease or injury. This type of strabismus can occur after head trauma or a neurological disease. It is important to note that epicanthal folds can give a false impression of strabismus.

Treatment.

In nonparalytic strabismus the refractory error is usually corrected with eyeglasses. When paralytic strabismus is seen during early infancy, the physician may recommend that the unaffected eye be covered by a patch until the infant is old enough to wear glasses. The affected eye may improve through use and often becomes normal. Eye exercises and glasses are effective ways of treating the condition medically. If they do not help, surgery should be considered. It is generally performed when the child is 3 or 4 years of age. Early correction is necessary to prevent amblyopia. If strabismus is left untreated, blindness in the affected eye may result because the brain tends to obliterate the confusing double image by disabling the eye.

Nursing Care.

The child undergoing surgery for strabismus may be hospitalized for only a brief period. The surgery involves structures outside the eyeball; therefore the child is allowed to be up and about postoperatively. Eye dressings are kept at a minimum, and elbow restraints may be sufficient to keep the child from touching the dressings.

Prevention of Eyestrain.

Children who are beginning to read need books with large type in which the letters are spaced far apart. The lighting must be adequate and without glare. Chairs and desks must be of the proper height.

Symptoms that may indicate eyestrain include inflammation, aching or burning of the eyes, squinting, a short attention span, frequent headaches, difficulties with schoolwork, or an inability to see the blackboard. It is important for the nurse to observe the child for eyestrain, to teach proper eye care, to prevent complications of eyestrain or strabismus, to refer as needed for follow-up care, and to assist in rehabilitation.

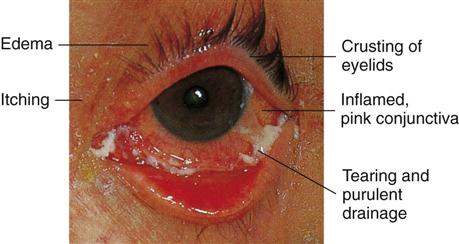

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis (conjungere, “to join together,” and itis, “inflammation”) is an inflammation of the conjunctiva, or the mucous membrane that lines the eyelids (Figure 23-5). It is caused by a wide range of bacterial and viral agents, allergens, irritants, toxins, and systemic diseases. Conjunctivitis that occurs with viral exanthems such as measles are usually self-limiting. It is common in childhood and may be infectious or noninfectious. The acute, infectious form is commonly referred to as pinkeye. Pinkeye is considered no longer contagious after 24 hours of appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Conjunctivitis can also result from an obstruction of the lacrimal duct. In general, the common forms of conjunctivitis respond to warm compresses and topical antibiotic eye drops or eye ointments. Ointments blur vision and are not generally used during daytime hours in the ambulatory child.

The nurse instructs parents to administer the eye medication for the prescribed time to prevent recurrence. Parents and older children are taught to wipe secretions from the inner canthus downward and away from the opposite eye. Because conjunctivitis spreads easily, affected children should use separate towels and be instructed to wash their hands frequently. Ophthalmia neonatorum, an acute conjunctivitis in the newborn, is discussed in Chapter 6. Allergic conjunctivitis is often associated with allergic rhinitis (rhin, “nose,” and itis, “inflammation”) in children with hay fever. Symptoms include itching, tearing of one or both eyes, and edema of the eyelids and periorbital tissues. The child may appear distracted and irritable.

Hyphema

Hyphema, the presence of blood in the anterior chamber of the eye, is one of the most common ocular injuries. It can occur from either a blunt or a perforating injury. Blows from flying objects (e.g., baseball, snowball) and forceful coughing or sneezing can cause this condition. These accidents are common among active school-age children. Hyphema appears as a bright red or dark red spot in front of the lower portion of the iris.

Treatment includes bed rest and topical medication. The head of the bed is elevated 30 to 45 degrees to decrease intraocular pressure and decrease intracranial pressure if there is an associated head injury. The condition generally resolves itself without residual problems.

Retinoblastoma

Pathophysiology.

Retinoblastoma is a malignant tumor of the retina of the eye. There are hereditary and spontaneous forms. The average ages at diagnosis are 12 months for bilateral tumors and 21 months for unilateral tumors (Kliegman et al., 2007). Gene-mapping techniques have shown chromosome 13 to be affected in hereditary forms. Chromosome 13 is also known to cause other congenital defects.

Manifestations.

A yellowish white reflex is seen in the pupil because of a tumor behind the lens. This is called the cat’s eye reflex or leukokoria (leuk, “white,” and kore, “pupil”). This may be accompanied by loss of vision, strabismus, hyphema and, in advanced tumors, pain. Metastasis to the unaffected eye is common in unilateral tumors. When retinoblastoma is suspected in children, an examination is performed using an anesthetic so the pediatric ophthalmologist may carefully examine the fundus of the eye.

Treatment and Nursing Care.

The standard treatment for unilateral disease is enucleation (removal) of the eye if there is no possibility of saving the vision. Small tumors are treated with laser photocoagulation to destroy the blood vessels supplying the tumor. Larger tumors can be treated with chemotherapy or external beam irradiation.

On return from surgery for enucleation, the child has a large pressure dressing on the eye. Elbow restraints may be necessary to prevent removal of the dressing. The bandage is observed for bleeding, and the vital signs are assessed. In a few days the surgeon removes the dressing and applies an eye patch. Other structures of the eye, such as the lids, lashes, and tear glands, are not affected. An eye prosthesis is fitted when the socket has healed. Instructions for care of the prosthesis are provided at the time of final fitting. Providing education and emotional support of the child and family and referral to the multidisciplinary health care team are essential.

The Nervous System

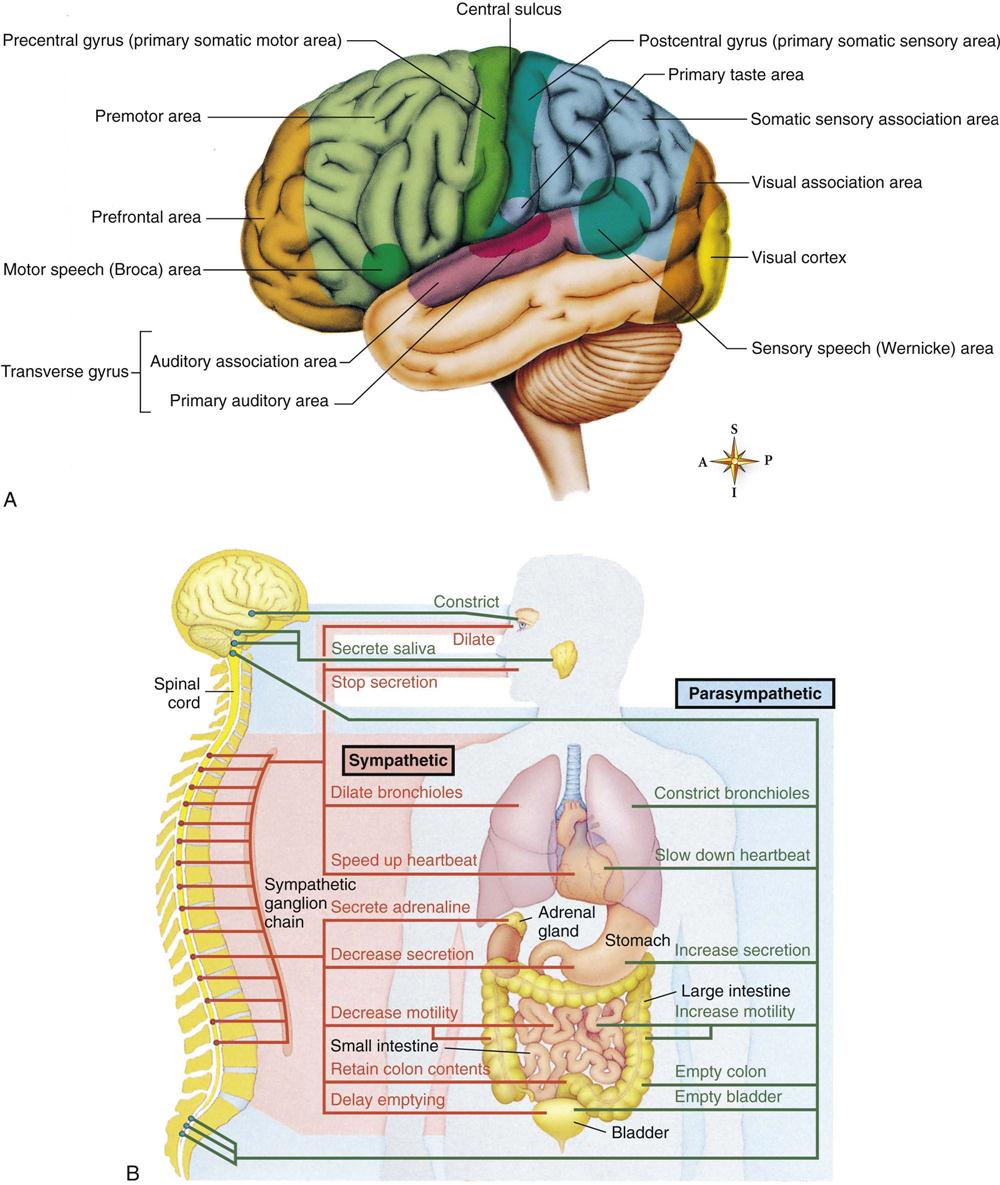

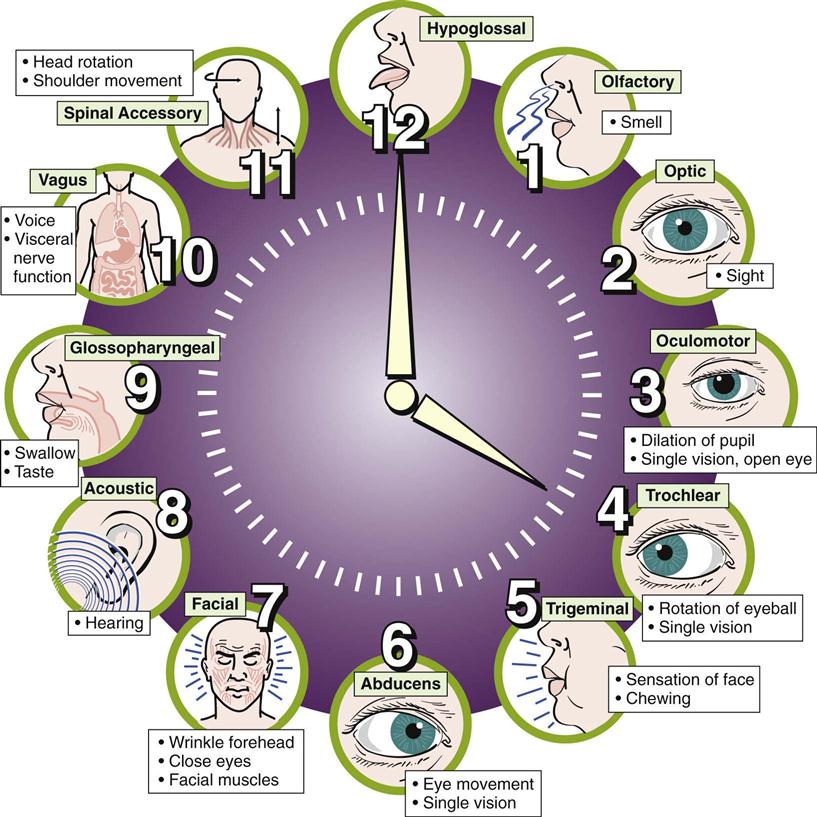

The nervous system is the body’s communication center; it receives and transmits messages to all parts of the body. It also records experiences (memorization) and integrates certain stimuli (learning). The anatomy of the nervous system is depicted in Figure 23-6. Neural tube development occurs during the third to fourth week of fetal life. This eventually becomes the central nervous system (CNS). The fusing process of the neural tube is critical. Its failure to fuse may lead to congenital conditions such as spina bifida (see Chapter 14). Most neurological disabilities in childhood result from congenital malformation (birth defects), brain injury, or infection. The 12 cranial nerves and their functions are shown in Figure 23-7.

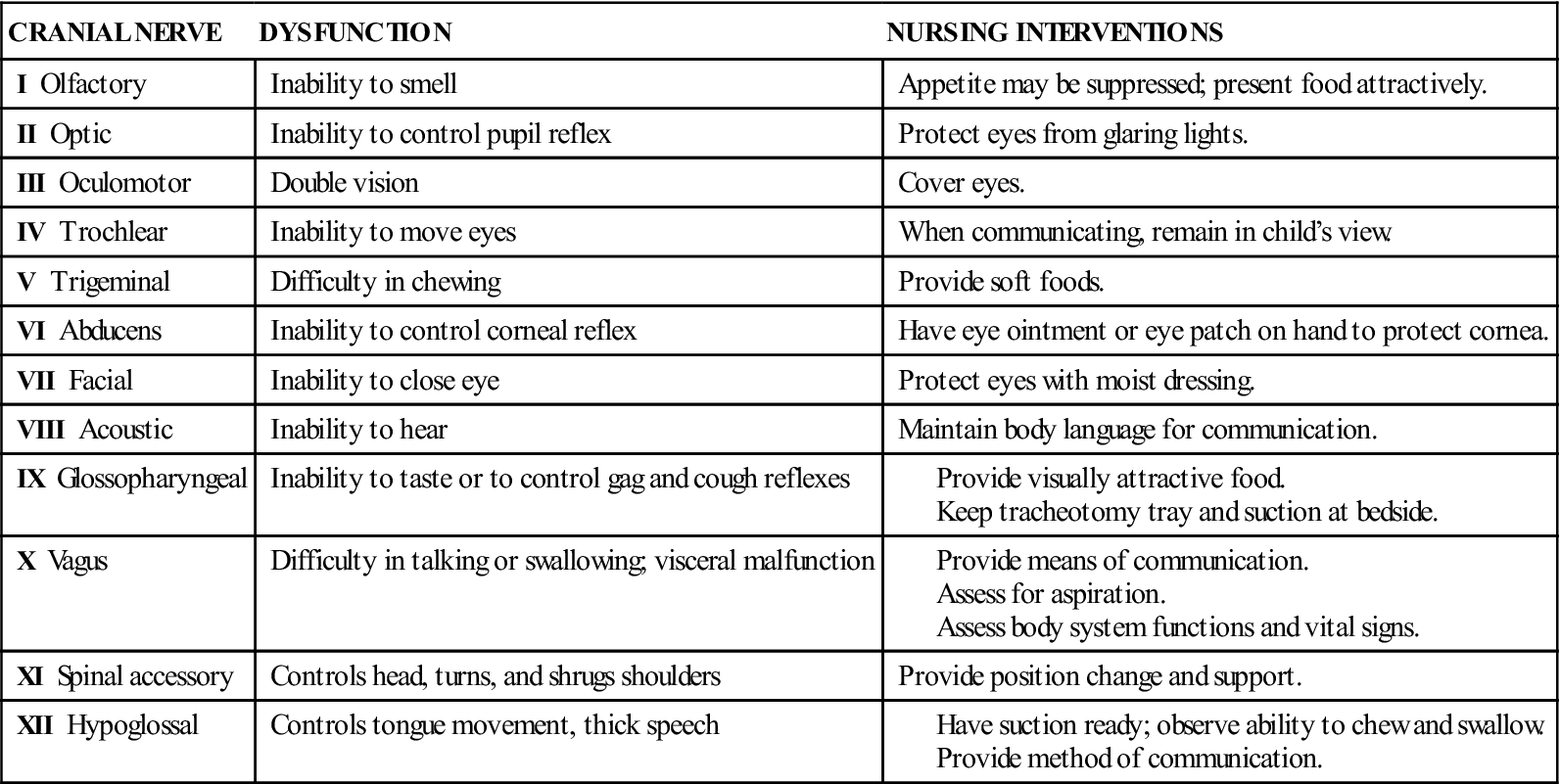

Central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction may be detected by a neurological check (see Box 23-6 and Table 23-6), skull x-ray films, electroencephalography (EEG), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electromyography, and other methods. The reflexes of the newborn are good indicators of neurological health. A decreased level of consciousness in the ill child may be an indication of a neurological problem. Box 23-1 describes the causes of altered level of consciousness. In the finger-nose test (used to determine coordination), the child is asked to extend the arm and then to touch his or her nose with the index finger. This is done with the eyes opened and closed. The inability to balance on one foot in a school-age child necessitates further follow-up. The 12 cranial nerves, selected forms of dysfunction, and nursing interventions are described in Table 23-1.

Table 23-1

The 12 Cranial Nerves: Selected Dysfunctions and Nursing Interventions

Disorders and Dysfunction of the Nervous System

Reye’s Syndrome

Pathophysiology.

Reye’s syndrome is an acute noninflammatory encephalopathy (pathology of the brain) and hepatopathy (pathology of the liver) that follows a viral infection in children. There may be a relationship between the use of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) during a viral flu or illness such as chickenpox (varicella) and the development of Reye’s syndrome. For this reason, aspirin use is generally contraindicated for the pediatric population. Some studies show that a genetic metabolic defect triggers Reye’s syndrome.

Manifestations.

Liver cell pathology causes an accumulation of ammonia in the blood. Toxic levels of ammonia cause cerebral manifestations (e.g., cerebral edema, increased intracranial pressure [ICP]), which results in neurological changes such as altered behavior, altered level of consciousness, seizures, and coma.

In children, the sudden onset of effortless vomiting and altered behavior (e.g., lethargy, combativeness) or altered level of consciousness after a viral illness is characteristic of Reye’s syndrome. The results of blood tests assessing liver function will be abnormal. In infants, diarrhea, hypoglycemia, tachypnea with apneic episodes, and seizures may occur approximately 1 week after a respiratory illness.

Prevention.

The education of the public concerning the dangers of using salicylate-containing medications during viral illnesses such as varicella in children may have contributed to the decline in the occurrence of Reye’s syndrome. The availability of the varicella vaccine may also have an impact on the reduced incidence of Reye’s syndrome.

Treatment.

Early treatment can result in recovery with some neuropsychological deficits. However, progression to the acute stage is often rapid and unpredictable. The goals of treatment include reducing ICP and maintaining a patent airway, cerebral oxygenation, and fluid and electrolyte balance.

Frequent assessment of vital signs and a careful assessment of neurological status are essential. Observation for signs of bleeding is important because liver dysfunction causes blood-clotting abnormalities. Parental education and support are necessary. Encouraging parents to participate in their child’s care helps to reduce the parents’ and child’s level of anxiety.

Sepsis

Sepsis is the systemic response to infection with bacteria and can also result from viral and fungal infections. Sepsis causes a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) due to the endotoxin of the bacteria that causes tissue damage. Untreated sepsis results in septic shock, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and death. Children who are immunocompromised, have neutropenia, or are in intensive care receiving invasive therapy are at increased risk for developing sepsis.

Manifestations.

Manifestations of sepsis include fever, chills, tachypnea, tachycardia, and neurological signs such as lethargy. Septic shock is not diagnosed by a decrease in blood pressure because initially, the infant’s body compensates for the poor circulation and tissue perfusion by increasing the heart rate and vasoconstriction of peripheral blood vessels. Hypotension is an ominous sign that may indicate the body is unable to compensate adequately and cardiorespiratory arrest is about to occur. Laboratory test results may include positive blood cultures, reduced fibrinogen and thrombocyte levels, and the presence of immature white blood cells. Neutropenia (neutrophil count below 1000/mm3) is an ominous sign. The nursing responsibilities include monitoring neurological status and vital signs; observing for shock; and maintaining strict standard and expanded precautions (see Appendix A). Intravenous antibiotics are prescribed. To prevent sepsis, immunization against H. influenzae type B (Hib) and administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) are recommended for all children between 2 months and 4 years of age.

Meningitis

Pathophysiology.

Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges (the covering of the brain and spinal cord). Various organisms can cause bacterial meningitis. Organisms may invade the meninges indirectly by way of the bloodstream (sepsis) from centers of infection such as the teeth, sinuses, tonsils, and lungs, or directly through the ear (otitis media), or from a fracture of the skull.

Bacterial meningitis is often referred to as purulent, that is, pus forming, because a thick exudate surrounds the meninges and adjacent structures. This can lead to certain sequelae such as subdural effusion and, less frequently, hydrocephalus. The peak incidence for bacterial meningitis is between 6 and 12 months of age. Meningococcal meningitis is readily transmitted to others. Meningitis is less common in children older than 4 years of age. H. influenzae is the most common causative agent. H. influenzae type B vaccine and PCV have decreased the incidence of bacterial meningitis. The approaches to nursing care for all types of meningitis are similar.

Manifestations.

The symptoms of purulent meningitis result mainly from intracranial irritation. They may be preceded by an upper respiratory infection and several days of gastrointestinal symptoms such as poor feeding. Severe headache, drowsiness, delirium, irritability, restlessness, fever, vomiting, and stiffness of the neck (nuchal rigidity) are other significant symptoms. A characteristic high-pitched cry is noted in infants. Seizures are common. Coma may occur fairly early in the older child. In severe cases, involuntary arching of the back caused by muscle contractions is seen (Figure 23-8). This condition is called opisthotonos (opistho, “backward,” and tonos, “tension”). The presence of petechiae (small hemorrhages beneath the skin) suggests meningococcal infection. Diagnosis is confirmed by examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree