The Adolescent

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. List major physical changes that occur during adolescence.

3. Identify two major developmental tasks of adolescence.

4. Discuss three major theoretical viewpoints on the personality development of adolescents.

5. List five life events that contribute to stress during adolescence.

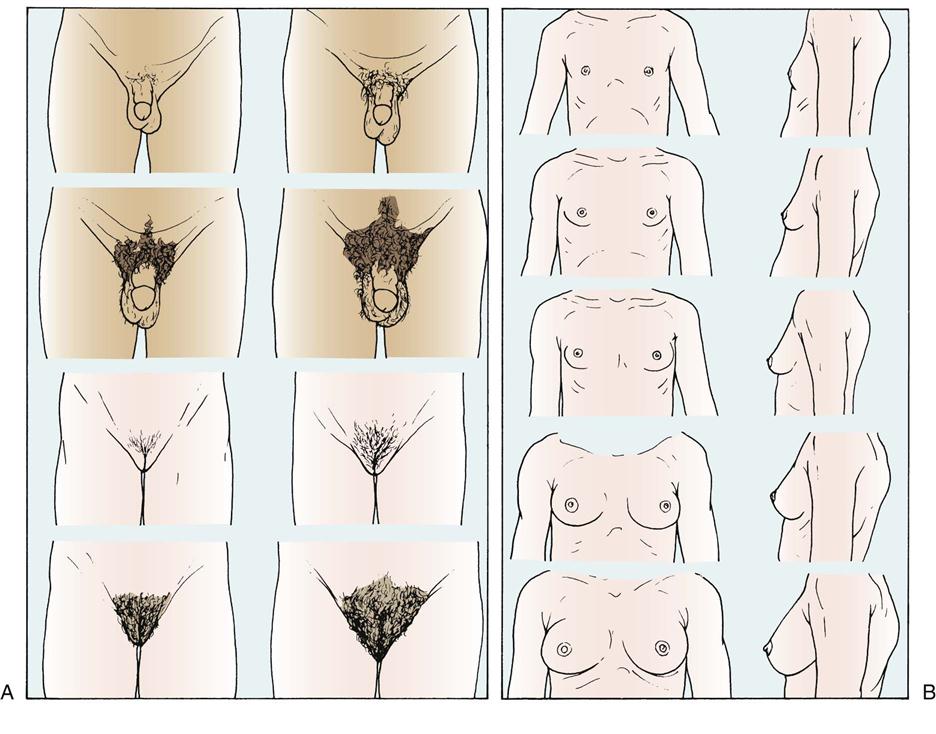

6. Describe Tanner’s stages of breast development.

7. Describe menstruation to a 13-year-old girl.

8. Identify two ways in which a person’s cultural background might contribute to behavior.

10. List three guidelines of importance for the adolescent participating in sports.

11. Summarize the nutritional requirements of the adolescent.

12. Discuss two main challenges during the adolescent years to which the adolescent must adjust.

13. List a source for planning sex education programs for adolescents.

14. Discuss the common problems of adolescence and the nursing approach.

Key Terms

abstract reasoning (p. 452)

adolescence (p. 451)

asynchrony (p. 452)

cliques (p. 458)

epiphyseal closure (ĕp-ĭ-FĬZ-ē-ăl CLŌ-zhŭr, p. 456)

formal operations (p. 460)

gay (p. 462)

gender roles (p. 452)

growth spurt (p. 452)

homosexual (p. 462)

intimacy (p. 452)

lesbian (p. 462)

menarche (mĕ-NĂHR-kē, p. 455)

puberty (p. 452)

self-concept (p. 456)

sexual maturity ratings (SMRs) (p. 456)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

General Characteristics

Adolescence is defined as the period of life beginning with the appearance of secondary sex characteristics and ending with cessation of growth and emotional maturity. The term comes from the Latin word adolescere, meaning “to grow up.” Adolescence is often divided into early, middle, and late periods because the 13-year-old adolescent differs a great deal from the 18-year-old adolescent. Middle adolescence appears to be the time of greatest turmoil for most families. Perhaps one of the most characteristic features of adolescence is its uncertainty. It is a period of life that in our culture lasts a comparatively long time and involves a great number of adjustments. The major tasks of adolescence include establishing an identity, separating from family, initiating intimacy, and developing career choices for economic independence. Some of the major theories of development are summarized in Box 20-1. Life is never dull when there are adolescents in the family. The surge toward independence becomes more and more pronounced, making it practically impossible for adolescents to get along with their parents, who represent authority. When adolescents submit to parental wishes, they may feel humiliated and childish. If they revolt, conflicts arise within the family. Parents and adolescents must weather the storm together and try to discover solutions that are relatively satisfactory to all.

Numerous other factors account for the restlessness of adolescents. Their bodies are rapidly changing, and they experience intense sexual drives. They want to be accepted by society, but they are not sure how to attain this goal. Adolescents question life and search to find what psychologists call their sense of identity; they ask, “Who am I?” “What do I want?” This is followed by the intimacy stage, in which adolescents must learn to avoid emotional isolation. They must face the fear of rejection in shared activities such as sports, in close friendships, and in sexual experiences. The older adolescent thinks about the future and is generally idealistic. Jean Piaget and other investigators indicate that during this time adolescents reach the final stages of abstract reasoning, logic, and other symbolic forms of thought, which increases sophistication in moral reasoning.

These facts sound complicated in themselves, but they are intensified by a world that is constantly changing. Gender roles are less well-defined in many households, and parents may not be traditional role models for their children. Many adolescents live in single-parent homes or with working relatives where little, if any, supervision is available.

Conformity is one of the strongest needs of the adolescent in society. Today, with electronic technology bringing common experiences to people all over the world via radio, television, and computers, the combined pressure to conform often overrides cultural or traditional practices. Assimilation is beginning to occur via technology.

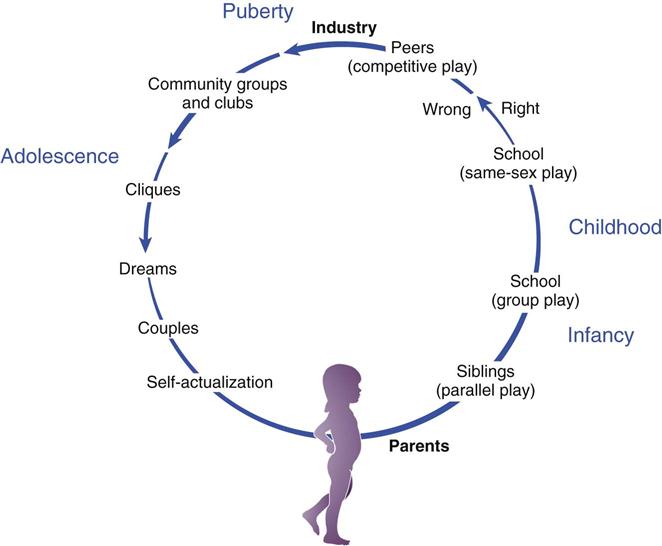

The needs of the family often compete with the needs of the adolescent when parents try to push the adolescent into an activity or career that meets the parent’s own personal need or dreams. Parents must be guided to enjoy the interests and activities of the adolescent without imposing their personal desires. The main challenges of the adolescent years include adjusting to rapid physical and physiological changes, maintaining privacy, coping with social stresses (Figures 20-1 and 20-2) and pressures, maintaining open communication, and developing positive health care practices and lifestyle choices.

Growth and Development

Physical Development

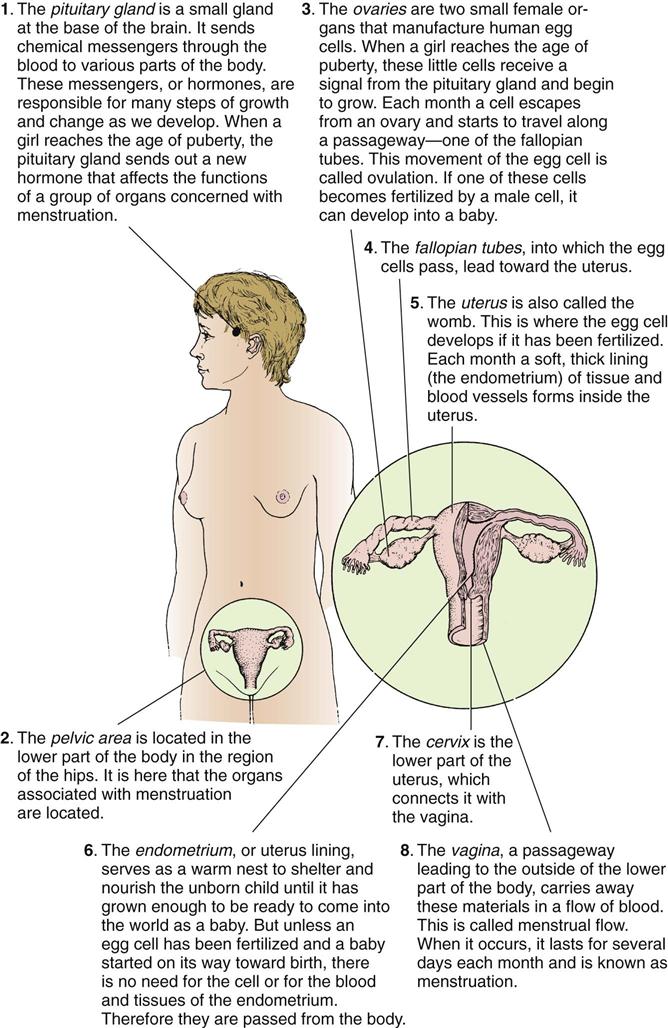

Preadolescence is a short period immediately preceding adolescence. In girls it comprises the ages of 10 to 13 years and is marked by rapid changes in the structure and function of various parts of the body. It is distinguished by puberty, the stage in which the reproductive organs become functional and secondary sex characteristics develop. Both sexes produce male hormones (androgens) and female hormones (estrogens) in comparatively equal amounts during childhood. During puberty the hypothalamus of the brain signals the pituitary gland to stimulate other endocrine glands—the adrenals and the ovaries or testes—to secrete their hormones directly into the bloodstream in differing proportions (more androgens in the boy and more estrogens in the girl).

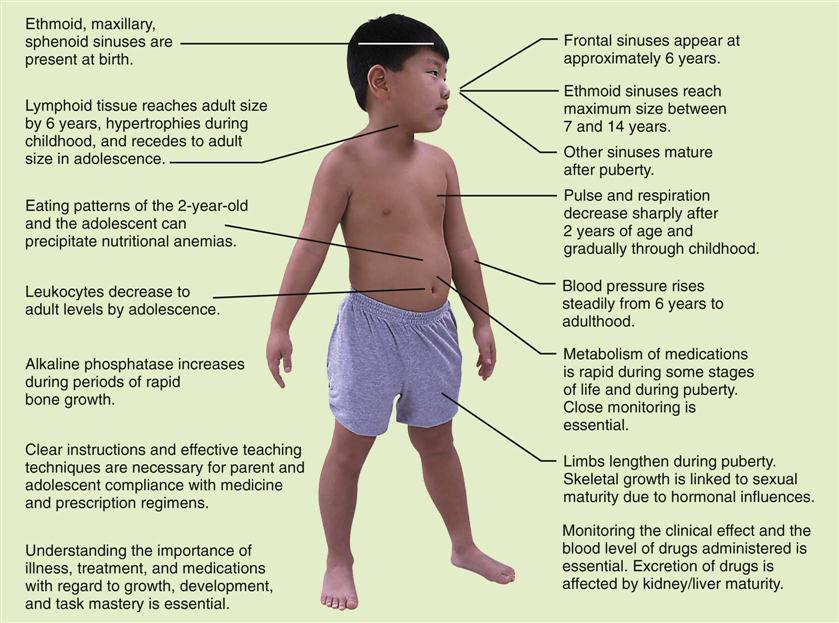

The age of puberty varies and is somewhat earlier for girls than for boys. The final 20% of mature height that is achieved during adolescence is called the growth spurt and usually occurs by 18 years of age. The major cause of weight gain is the increase in skeletal mass. The implications of growth and development for nursing assessments are illustrated in Figure 20-3.

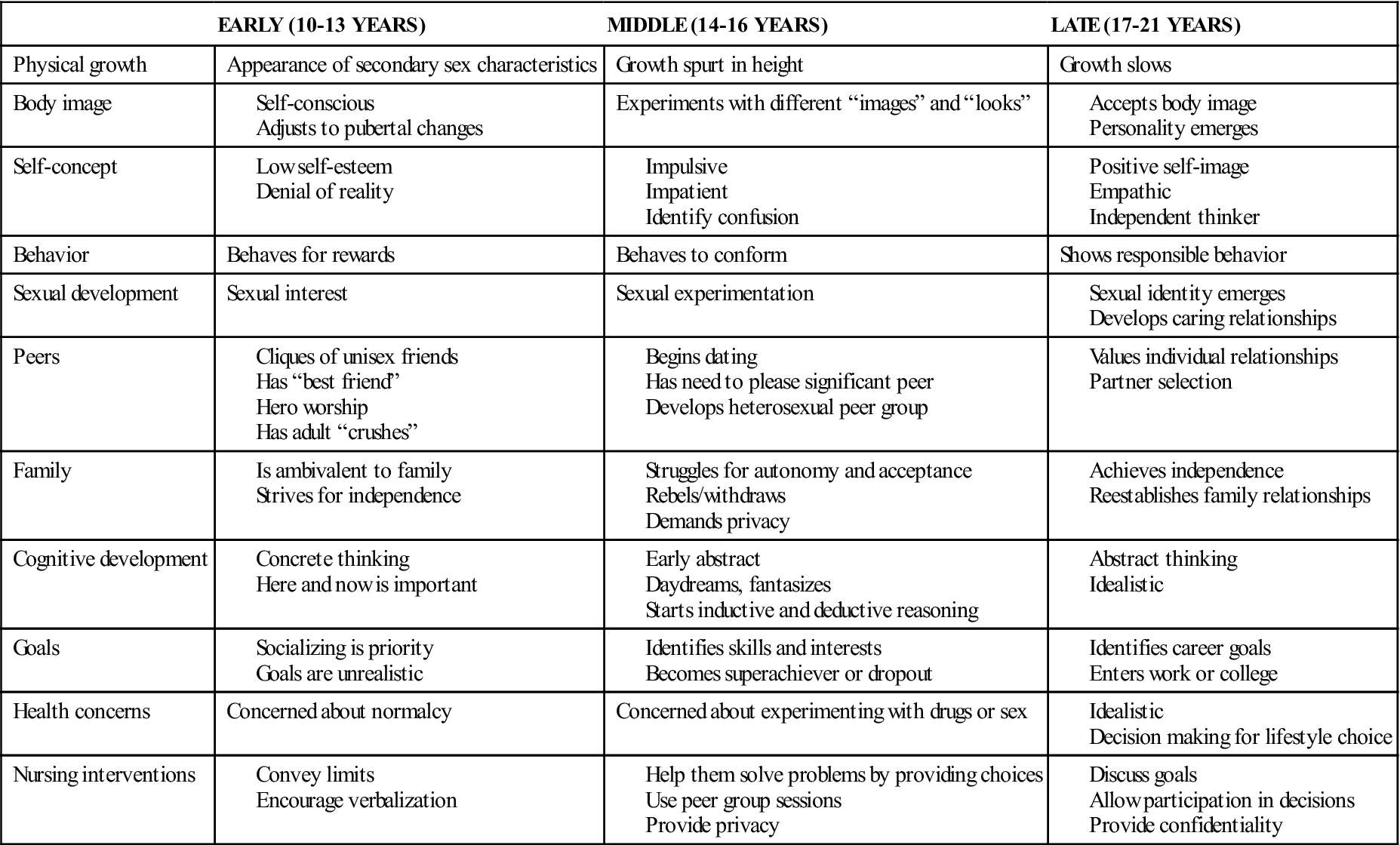

The general appearance of the adolescent tends to be awkward, that is, long-legged and gangling; this growth characteristic is termed asynchrony because different body parts mature at different rates. The sweat glands are very active, and oily skin and acne are common. Both sexes mature earlier and grow taller and heavier than in past generations. Because of the gross motor development that occurs during adolescence, teenagers can gain satisfaction from sports. Table 20-1 outlines the growth and development of adolescents.

Table 20-1

Growth and Development of the Adolescent

Boys

During fetal life the placental chorionic gonadotropin stimulates Leydig cells to secrete testosterone. Thus weeks 8 to 12 of fetal life are important in the sexual development of the male (XY) child. Luteinizing hormone (LH) maintains testosterone levels. Serum levels of LH increase during sleep 1 to 2 years before puberty. The secretion of gonadotropin stimulates gonad enlargement and the secretion of sex hormones. The interaction among the hypothalamus, pituitary, and gonads supports the development of puberty.

In boys, puberty begins with hormonal changes between 10 and 13 years of age. The shoulders widen, the pectoral muscles enlarge, and the voice deepens. Hair begins to grow on the face, chest, axillae, and pubic areas (Figure 20-4 and Box 20-2). Enlargement of the testicles and of internal structures and pigmentation of the scrotum are followed by enlargement of the penis. Erections and nocturnal emissions take place. The production of sperm begins between 13 and 14 years of age. An athletic scrotal support device (jockstrap) is necessary for boys participating in sporting events or for any activity in which support and protection of the genitalia are required. Athletic supporters not only support and protect the genitalia but also prevent embarrassment from exposure. Athletic supporters are purchased by size. Good personal hygiene is necessary because heat and friction may lead to jock itch, a fungal infestation of the groin. Sharing athletic supporters is discouraged.

Some experts recommend that after puberty boys examine their testes during or after a hot bath or shower. Each testicle is examined using the index and middle fingers of both hands on the underside of the testicle and the thumbs on the top of the testicle. The testicles are gently rolled between the thumb and the fingers to feel for abnormalities. Testicular and scrotal self-examinations are performed once a month. If a lump is discovered, it should be reported immediately to a health care provider (American Cancer Society, 2010).

Girls

Pubertal changes in girls occur 6 months to 2 years before they occur in boys. Puberty is easily recognized in girls by the onset of menstruation (Figure 20-5). The first menstrual period is called the menarche. It commonly occurs about age 12 or 13 years, but this varies. It may occur as early as age 10 years or as late as age 15 years. Secondary sex characteristics become more apparent before the menarche. Fat is deposited in the hips, thighs, and breasts, causing them to enlarge (see Box 20-2).

At this time the adolescent girl may need to be fitted for a bra. Measurements must be ascertained and various styles tried on for comfort. Straps should fit so that they do not continually fall from the shoulders. Cups need to be large enough to support fullness near the underarms. The garment must fit across the back so that it is not uncomfortably tight. Adolescents generally like attractive undergarments that have some type of lace trim. Sports bras are available for girls who participate in active sports. Puberty is a good time to begin teaching breast self-examination (see Skill 11-1). Instructional materials are available through the American Cancer Society.

The external genitalia grow. Hair develops in the pubic area (see Figure 20-4 and Box 20-2) and the underarms. It is important to note that in ballet dancers, runners, gymnasts, and adolescents engaged in other athletic activities that involve a lean body and high level of physical activity, the mechanisms affecting puberty can be altered and cause a delay in the onset of menarche. Energy balance, activity, and nutrition are important factors to evaluate when menstruation is delayed. Further growth can no longer take place when the ends of the long bones knit securely to their shafts (epiphyseal closure). See Chapter 2 for a detailed discussion of the physiology of reproductive organs.

Psychosocial Development

Sense of Identity

Physical growth and sexual interest correlate with sexual maturity. Cognitive growth and social changes correlate with chronological age and placement in school. Stress can increase when physical growth and cognitive growth occur at different rates in the same adolescent. Although the early-maturing male often finds positive social adjustment and acceptance, early-maturing females are often embarrassed and develop low self-esteem. The adolescent’s desire for freedom and independence is extremely important and necessary for developing individuality. To accomplish this, young persons must reject their childhood self and often the people most closely associated with it. Erikson identifies the major task of this group as identity versus role confusion. Emancipation is a critical element in the establishment of identity.

Adolescents want to be people in their own right, and they “try on” different roles. Self-concept (one’s view of oneself) fluctuates during this time and is molded by the demands of parents, peers, teachers, and others. Interaction with others helps adolescents determine who they are and in what direction they want to proceed. This process is more difficult for low-income minorities and is complicated by many factors, such as illness, broken homes, and the extent of formal education. Young persons who are unable to master confusion and establish an identity may become rigid in their actions, bewildered, or depressed, or they may cling to the conformity of peer groups long after the need should have passed. Some show an inordinate need for something “new and exciting.” They may experience low self-esteem and alienation, and they may confront many other difficulties on entering the adult world.

Sense of Intimacy

Developing intimacy is closely entwined with the resolving of a person’s sense of identity. As adolescents move toward young adulthood, they become ready to take the risks of close affiliations and friendships and to establish relationships with the opposite sex (Figure 20-6). Avoidance of building these relationships may lead to a deep sense of isolation. Adolescence is a period of trying and testing. Disagreements with parents often revolve around dating, the family car, money, chores, school grades, choice of friends, smoking, sex, and the use of illicit drugs. The young person questions parental values and morals and is particularly sensitive to hypocrisy.

Adults who associate with adolescents should try to create an atmosphere of interest and understanding. Adolescents must know that adults care. Adolescents need practice in making decisions that must be respected even if they have made a mistake. Parents should set limits and expect them to be challenged but not exceeded. Parents and nurses who see other people’s intrinsic worth, feel good about themselves, and do not see the adolescent’s behavior as a reflection on their parenting or nursing provide a more secure environment for growth. Loving detachment is not easy, but it is an effective tool in dealing with adolescents.

Cultural and Spiritual Considerations

Americans are multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual. The value of independence as a goal of maturational and emotional development may not be adopted by all. The traditional Chinese do not recognize the period of adolescence; there is no word for it in their language. Many immigrants and Americans of Asian descent come from societies that are patriarchal and highly structured and have distinct social roles. The good of the family takes precedence over personal goals. The protection of family image and neighborhood reputation is essential.

As part of a search for their identity, adolescents focus on the values and ideals of the family and decide either to embrace them or to separate from them. Adolescents often perceive their feelings and thoughts as unique and therefore do not express their feelings freely. Adolescents can understand abstract concepts and symbols, and exposure to religion and religious practices other than those experienced within their own traditional family can help them stabilize their group identity (Figure 20-7). The nurse’s awareness of these and other cultural influences on the adolescent’s behavior will help in the effort to provide holistic care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree