Kathleen F. Jett

Neurological disorders

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

You know I lived a hard life – I smoked since I was a kid, didn’t take care of myself, but somehow I never thought I might have a stroke. Now I have had one and life will never be the same.

Henry at 72

I just don’t understand what she is trying to tell me. I know it must be very frustrating for her to feel kind of trapped inside and not being able to speak, but I am frustrated too, not knowing what she needs!

Angela, a new nurse

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Differentiate a transient ischemic attack from a stroke.

• Identify strategies to decrease the likelihood of a stroke.

• Contribute to the early recognition of Parkinson’s disease.

• Develop a strategy to promote safety in persons with neurological disorders.

Glossary

Bradykinesia Abnormally slowed movements of the body.

Dysarthria A speech disorder caused by weakness or incoordination of the muscles used for speech.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

In this chapter we review two of the most common neurological disorders seen in older adults, cerebrovascular disease and Parkinson’s disease. Each of these has the potential to significantly impair a person’s function and indeed affect every aspect of life. In as much, the role of the nurse is broad. In both of these the nurse plays an active role in helping the patient and the family navigate the rehabilitative process and minimize loss of function; this may include home visits to determine the safety measures needed in the environment. In case of cerebrovascular disease, the nurse is active in health promotion and disease prevention by ensuring prompt diagnosis and treatment at the time of the acute event (see the Healthy People box). Last, the gerontological nurse helps the elder and his or her significant others cope with the changes inherent in these disorders including grief support (see Chapter 25).

Cerebrovascular disease

Cerebrovascular disease is the most commonly occurring neurological disorder, and it is caused by an interruption of blood supply to the brain. Cerebrovascular disease is either ischemic or hemorrhagic in nature and it is manifested as either a stroke (the term cerebrovascular accident [CVA] is now discouraged) or a transient ischemic attach (TIA). Because the initial signs and symptoms are similar but the outcomes are different, diagnosis is geared toward identifying the specific cause and the location of the brain injury. Only when the cause is known can appropriate therapy be implemented.

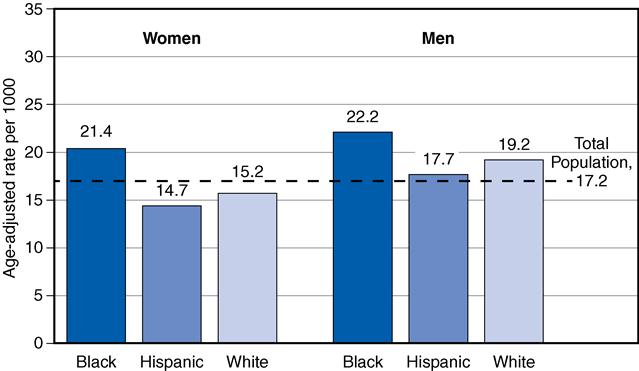

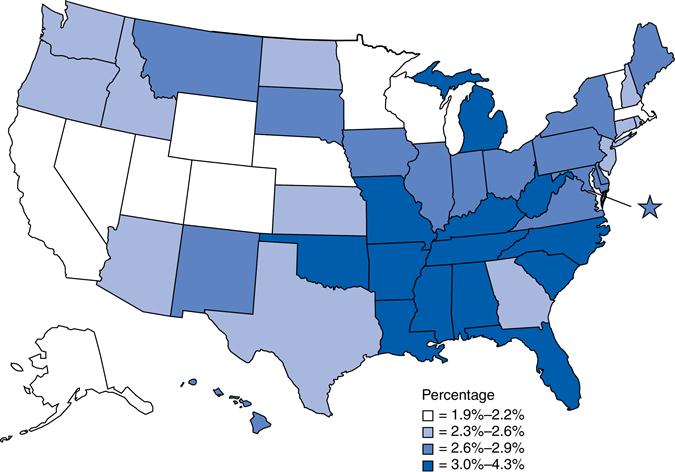

More than 75% of all strokes occur in persons older than 65 years of age. Strokes are twice as common among African Americans as whites, and Hispanics have the lowest rate of all. Hispanics and African Americans are significantly more likely to die as a result of the stroke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011) (Figure 20-1). The age-adjusted death rate is about equal in men and women. However, there are also significant regional differences (Figure 20-2).

Although the rate of strokes is decreasing, it remains the third most common cause of death behind heart disease and cancer for whites, African Americans, and Hispanics and the fifth leading cause of death for American Indians and Alaskan Natives (CDC, 2012). Each year about 795,000 people in the United States have a stroke, or one stroke every 40 seconds. For most people (610,000) this is a first-time event but for many others (185,000) it is a repeat event. Once every 4 minutes someone dies of a stroke (CDC, 2011).

Etiology

Ischemic events

The majority (87%) of all cerebrovascular events are ischemic in nature (CDC, 2011). The four main types and causes are (1) arterial disease, (2) cardioembolism, (3) hematological disorders, and (4) systemic hypoperfusion. Cardioembolism includes those caused by an arrhythmia such as atrial fibrillation, which is frequently seen in coronary heart disease (see Chapter 19). The use of antithrombotics (e.g., aspirin, warfarin) in persons with heart disease is an attempt to reduce the risk for stroke. Hematological disorders include coagulation disorders and hyperviscosity syndromes. Hypoperfusion leading to a stroke can occur from dehydration, hypotension (including overtreatment of hypertension), cardiac arrest, or fainting (syncope) (Graykowski, 2008).

A TIA is ischemic but clinically different from an ischemic stroke in that the symptoms of a TIA begin to resolve within minutes and all neurological deficits caused by it resolve within 24 hours. In some cases a TIA is followed by a stroke, but most strokes are not preceded by TIAs (Box 20-1).

Approximately 24% to 29% of those who have a TIA will have a stroke in the 5 years following the event (Goldstein, 2011). Up to 500,000 TIAs are diagnosed each year in the United States. More men than women have TIAs, with 101 cases per 100,000 men and 70 cases per 100,000 women. However, the most significant difference is by age, with 1 to 3 per 100,000 persons in those under 35 years of age but 1500 per 100,000 in those over 85 years of age.

Hemorrhagic events

Hemorrhagic strokes are less frequent than ischemic strokes but more life threatening. They are primarily caused by uncontrolled hypertension and less often by malformations of the blood vessels (e.g., aneurysms). Although the exact mechanism is not fully understood, it appears that the chronic hypertension causes thickening of the vessel wall, microaneurysms, and necrosis. When enough damage to the vessel accumulates, it is at risk for rupture. The spontaneous rupture may be large and acute or small with a slow leaking of blood into the adjacent brain tissue. In many cases, there is a rupture or seepage of blood into the ventricular system of the brain with damage to the affected tissue through necrosis or death of brain tissue (Boss, 2010a). Resolution of the event can occur only with the resorption of excess blood and damaged tissue.

Signs and symptoms of cerebrovascular disease

The first signs of both strokes and TIAs are acute neurological deficits consistent with the part of the brain affected. They are often preceded by a severe headache. In subarachnoid hemorrhages, the headache is not only sudden but also explosive, very severe, and without other neurological manifestations (Graykowski, 2008).

Some of the clinical signs and symptoms are suggestive of either ischemia or hemorrhage (Box 20-2). Persons with hemorrhage have more specific neurological changes, including seizures and more depressed level of consciousness than those with an ischemic stroke. If a person is deeply unresponsive following a stroke he or she is unlikely to survive (Boss, 2010a). Nausea and vomiting are suggestive of increased cerebral edema in response to an event of either type. Neurological changes may include alterations in motor, sensory, and visual function; coordination; cognition; and language and depend on the area of damage.

Diagnosis includes the determination and correction of possible extra-cerebral causes, if any (e.g., infection or hypoglycemia), confirmation of the type of stroke and identifying exactly where in the brain the damage has occurred. This is done through the use of a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Complications

After a TIA resolves, there should be no residual effect other than an increased chance of recurrence and the possible increased risk for stroke as noted earlier. Early complications of a simple stroke include extension of the amount of damage and recurrence. Brain edema is always a problem, and could result in obstructive hydrocephalus (Graykowski, 2008).

The potential long-term effects of a stroke may be minimal but also may include paralysis and hemiparesis limiting movement, and dysarthrias, dysphagias, and aphasias limiting speech. Post-stroke depression has been found to negatively affect rehabilitation. Whenever paralysis or hemiparesis occurs, the development of spasticity or unusually tight muscles in the affected limb(s) is a risk. Spasticity can lead to contractures if it is not managed well and even sometimes when it is. Pain in the affected side is not uncommon and may be treated with muscle relaxants or medications specific for neuropathic pain (see Chapter 8). The medications, added to the potential limitations of the stroke, significantly increase the risk for falls. Other complications include blood clots (deep vein thrombosis [DVT]) in the affected limb, pressure ulcers, aspiration pneumonia, and urinary tract infections (Llinas, 2010).

Management

All actual or potential cerebrovascular events are considered emergencies and should be treated as such. However, because TIAs are highly transient they often resolve on their own before the person is even seen by a health care provider. Instead, the person reports “I think I had a small stroke last week” or they do not seek care at all. If the deficits and symptoms were fleeting, the diagnosis is made through the clinical interview. Management is considered preventive—to prevent recurrences and to decrease any possible risk factors for strokes (see the Healthy People box). The person and family are also instructed in the appropriate emergency response to the return of any signs or symptoms of a stroke or another TIA (see Box 20-1). Anticoagulant therapy has been proven to prevent recurrent cardioembolic strokes and TIAs. Aspirin, 81 to 325 mg/day, is the mainstay of therapy for elders with TIAs. However, for those who are aspirin sensitive, clopidogrel (Plavix) may be used (Llinas, 2010). Warfarin therapy or one of the newer related medications is usually used in persons to prevent another stroke and in those with atrial fibrillation to prevent the occurrence of the first stroke (Graykowski, 2008).

Acute management is accomplished in emergency departments and intensive care units. The acute management of the stroke requires careful attention to the accuracy of the diagnosis. For ischemic strokes caused by an embolism, the compromised circulation to the brain must be restored rapidly. This is done in emergency rooms and is called reperfusion therapy using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) if the facility is equipped to do so (see the Healthy People box).

If the person has had a hemorrhagic stroke and it is misdiagnosed, the bleeding will be rapidly accelerated by the rt-PA, and the person will die. The initial response to the hemorrhagic stroke is to find a means to stop the bleeding if possible.

About 90% of neurological recovery occurs within 3 months of the stroke; 10% occurs more slowly, especially after a hemorrhagic stroke (Porter & Kaplan, 2010-2011). At 18 months after the stroke, there tends to be a small decline. The inverse relationship between functional improvement and advanced age, social isolation, and emotional distress is clear. Recovery from stroke is affected by the location and extent of the brain damage. Difficulties and handicaps after stroke often involve neurological and functional deficits. Post–ischemic stroke management begins immediately with anticoagulants or antiplatelets and rehabilitation (see the Healthy People box).

Nowhere in the care of elders is the multidisciplinary team more essential than in the care of persons after a stroke. The assessment of needs is extremely complex; it requires evaluation by a team often coordinated by a rehabilitation nurse and includes a neurologist; a physiatrist; speech, occupational, and physical therapists; an ophthalmologist; a rehabilitation specialist; and a psychologist. It also may include a spiritual advisor. It always includes the person’s significant other, who may be involved with the day-to-day life. Acute support services are now available in specialized stroke centers. These have been found to improve outcomes in persons with ischemic strokes (Llinas, 2010).

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

The best approach to stroke, despite new therapies and medications, is prevention and prompt intervention. Identifying high-risk or stroke-prone elders is something nurses can do in the elders’ homes, in the community, or at the health facilities where the nurses work. In a quick assessment of risk factors (Box 20-3), the nurse can work with individuals to reduce their risk for stroke and teach them how to respond to any signs or symptoms (see the Healthy People box).