Kathleen F. Jett

Metabolic disorders

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

I can see that Anna is going to need a lot of help learning to manage her diabetes. I know now that I have already overwhelmed her with brochures and information. She just looked frightened to death, and she really just has a mild elevation in blood sugar; it could probably be controlled with diet and exercise. I will call her tomorrow and see if she is less anxious.

Anna’s gerontological clinical nurse specialist

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Explain the risks for and complications of endocrine disorders in older adults.

• Describe the assessment necessary in the screening and monitoring of persons with diabetes.

• Identify the unique aspects of diabetes management in older adults.

• Explain the important components of diabetes management.

• Develop a nursing care plan for elders with endocrine disorders.

• Discuss the nurse’s role in care for persons with endocrine disorders.

Glossary

Hgb A1c (Glycosylated hemoglobin) A blood test that measures the amount of glucose in the hemoglobin of red blood cells averaged over the 90-day life span of the cell.

Insulin resistance A condition in which body cells are less sensitive to the insulin produced by the pancreas, thus impairing normal glucose metabolism.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Although the exact relationship between normal changes with aging and endocrine function is unknown, endocrine disorders, especially hypothyroidism and diabetes, most commonly occur in later life. It has been suggested that these are associated with the increase in autoimmune activity of the body as it ages (see Chapter 5) but the findings are inconclusive. Nonetheless, due to the large number of elders who are affected, the gerontological nurse should have a working knowledge of these conditions to provide the care needed to promote healthy aging.

Thyroid disease

The thyroid is small gland in the neck which stores and secretes thyroid hormones, which regulate metabolism and affect nearly every organ in the body. It is estimated that about 5% of all Americans have overt hypothyroidism (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [NIDDK], 2012c) and about 1% have hyperthyroidism (NIDDK, 2012b). Women are more likely to have both, affecting an estimated 5% to 10% of those over 65 years of age (Brashers & Jones, 2010). Usually easy to diagnose, many of the signs and symptoms in an older population are unfortunately non-specific, atypical, or absent. Signs such as decline in cognitive function or functional status or even an irregular heartbeat may be incorrectly attributed to normal aging, another disorder, or to side effects of medications when it is actually a thyroid disturbance.

Hypothyroidism

The most common thyroid disturbance in older adults is hypothyroidism, that is, the failure of the thyroid to produce an adequate amount of the hormone thyroxine. The onset is often subtle, developing slowly, and thought to be caused most frequently by chronic autoimmune thyroiditis or an inflamed thyroid. It may be iatrogenic, resulting from radioiodine treatment, a subtotal thyroidectomy, or medications. It can also be caused by a pituitary or hypothalamic abnormality (Jones et al., 2010).

The person may complain of heart palpitations, slowed thinking, gait disturbances, fatigue, weakness, or heat intolerance. These and other symptoms and signs are often evaluated for other causes before the possibility of hypothyroidism is considered. Blood tests to measure the amount of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and a free thyroxine (FT4) are used for diagnosis. An elevated TSH combined with a low FT4 indicates that the pituitary is working extra hard to get the thyroid to secrete when it may not be able to do so (Brashers & Jones, 2010). The treatment is to replace the missing thyroxine, usually in the form of the medication levothyroxine. However, it can only be done slowly due to the toxicity of the drug, beginning with doses of 0.025 mg/day (Shorr, 2007). To advance a dose rapidly could be life threatening. Most older adults never need to advance to a higher dose.

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is a disease of the secretion of an excess amount of thyroxine. Graves’ disease is the most common cause in later life. Thyroid disease from multinodular toxic goiter and adenomas are also more common among older than younger adults. It can also result from ingestion of iodine or iodine-containing substances, such as those found in some seafood, radiocontrast agents, the medication amiodarone (a commonly prescribed antiarrhythmic agent), or too high a dose of levothyroxine. The same blood tests are done, this time the TSH would be very low and the FT4 high. However, FT4 is closely associated with protein levels in the blood. If protein is too low, the FT4 will be artificially low making diagnosis difficult, especially in the large number of medically frail elders with hypoproteinemia (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Compared to hypothyroidism, the onset of hyperthyroidism may be quite sudden. The signs and symptoms in the older adult include unexplained atrial fibrillation, heart failure, constipation, anorexia, muscle weakness, and other vague complaints. Symptoms of heart failure or angina may cloud the clinical presentation and prevent the correct diagnosis. The person may be misdiagnosed as being depressed or having dementia. On examination, the person is likely to have tachycardia, tremors, and weight loss. In elders a condition known as apathetic thyrotoxicosis, rarely seen in younger persons, may occur in which usual hyperactivity is replaced with slowed movement and depressed affect. If left untreated it will increase the speed of bone loss and is as life threatening as hypothyroidism.

Complications

Complications occur both as the result of treatment and in the failure to diagnose and therefore failure to treat in a timely manner. Myxedema coma is a serious complication of untreated hypothyroidism in the older patient. Rapid replacement of the missing thyroxine is not possible due to risk of drug toxicity. If the disease is not detected until quite advanced, even with the best treatment, death may ensue.

Thyroxine increases myocardial oxygen consumption; therefore, the elevations found in hyperthyroidism produce a significant risk for atrial fibrillation and exacerbation of angina in persons with preexisting heart failure or may precipitate acute congestive heart failure (see Chapter 19).

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

The management of thyroid disturbances is largely one of careful pharmacological intervention and, in the case of hyperthyroidism, one of surgical or chemical ablation. As advocates, nurses can ensure that a thyroid screening test be done anytime there is a possibility of concern. The nurse caring for frail elders can be attentive to the possibility that the person who is diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, anxiety, dementia, or depression may instead have a thyroid disturbance. Although the nurse may see little that can be done to prevent thyroid disturbances in late life, organizations such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium have launched campaigns to inform consumers of the iodine and mercury found in seafood (www.seafoodwatch.org).

The nurse may be instrumental in working with the person and family to understand both the seriousness of the problem and the need for very careful adherence to the prescribed regimen. If the elder is hospitalized for acute management, the life-threatening nature of both the disorder and the treatment can be made clear so that advanced planning can be done that will account for all possible outcomes.

For the person in ongoing maintenance treatment, the nurse works with the person and significant others in the correct self-administration of medications and in the appropriate timing of monitoring blood levels and signs or symptoms which may indicate the need for a medication adjustment. Patient education includes instructions to always take the same brand, to take it at the same time every day and to not take any mineral products at the same time of the day, such as multivitamins, calcium, or some over-the-counter stomach preparations such as Tums (contain calcium) as these interfere with absorption (Shorr, 2007).

Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a syndrome of disorders of glucose metabolism resulting in hyperglycemia; that is, the body is unable to use the glucose that is both produced and ingested. Because glucose is necessary for life, DM is a life-threatening condition. The two main forms are type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 (T2DM). Additionally, gestational diabetes is that which happens for the first time when a woman is pregnant—usually with a very large fetus. Finally, of importance to older adults is steroid-induced diabetes, a unique circumstance caused by either long-term steroid use in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or acute steroid use following an infection such as pneumonia.

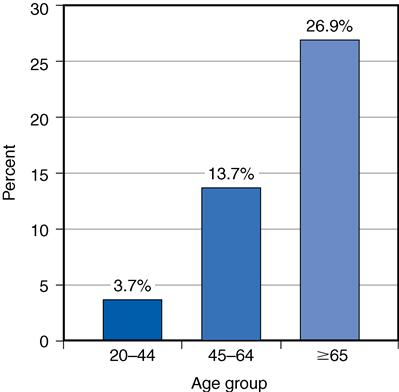

T1DM (formerly called insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus [IDDM] and juvenile onset) develops early in life and is a result of autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. The absence of insulin is incompatible with life and without replacement of the insulin, the person will soon die. It has been rare that someone with T1DM lives to late life. Among U.S. residents at least 65 years of age in 2010, 10.9 million or 26.9% had diabetes, the majority of these with T2DM (90% to 95%) (formerly called non–insulin dependent diabetes mellitus [NIDDM] or adult onset), making age alone a major risk factor (NIDDK, 2011). In this case, the pancreas makes insulin but either it does not make enough to keep up with the needs of the body and/or the tissues develop a resistance to naturally occurring insulin. The onset is usually insidious with few if any symptoms until end-organ damage has occurred. Older adults with T2DM often have other health problems, including problems with the metabolism of lipids and proteins. This considerably complicates providing care to them.

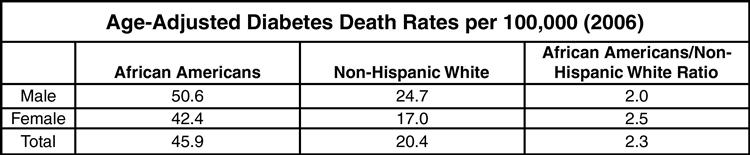

There are also a large number of persons of every age who have not yet been diagnosed or have conditions that may advance to DM if left untreated, specifically impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or impaired fasting glucose (IFG) (Box 17-1). Who is likely to get DM or even die from DM varies by ethnicity, place of residence, and age (Figures 17-1 and 17-2, Box 17-2). DM affects African Americans the most, or about 18.7%, especially women between 65 and 75 years of age. American Indian and Alaskan Natives have an overall rate double that of non-Hispanic whites (14.2%) but this varies by group, from 5.5% for Alaskan Natives to 33.5% for those in southern Arizona. DM affects approximately 11.8% of all Hispanic adults again with a great amount of variability; Cubans with the lowest (7.6%) and those from Puerto Rico with the highest (13.8%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011).

Signs and symptoms

The classic signs and symptoms of diabetes include thirst and excessive urinating as the body tries to reduce the relative concentration of glucose in the blood. Yet hyperglycemia appears to be well tolerated in later life and there may be no early warning symptoms until the person is found to be in a life-threatening (hyperosmolar nonketotic) coma. For unknown reasons diabetic coma is more common among African-American elders. It is not unusual to find asymptomatic older persons with fasting glucose levels of 300 mg/dL or higher or as low as 50 mg/dL. Early signs may instead be dehydration, confusion, or delirium and are very dangerous. Instead of urinary frequency, the high amount of glucose in the urine often causes incontinence. The catabolic state caused by lack of insulin causes polyphagia (excessive hunger) in younger persons but causes weight loss and anorexia in elders (lack of appetite). Other vague signs and symptoms include fatigue, nausea, delayed wound healing, and paresthesias; the later is a sign that the person has already had the disease for many years (Jones et al., 2010) (Box 17-3).