Theris A. Touhy

Cognitive impairment

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

“The Alzheimer’s patient asks nothing more than a hand to hold, a heart to care, and a mind to think for them when they cannot; someone to protect them as they travel through the dangerous twists and turns of the labyrinth. These thoughts must be put on paper now. Tomorrow they may be gone, as fleeting as the bloom of night jasmine beside my front door.”

Diana Friel McGowin, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease when she was 45 years old (McGowin, 1993, p. viii)

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Differentiate between dementia, delirium, and depression.

• Discuss the different types of dementia and appropriate diagnosis.

• Describe nursing models of care for persons with dementia.

• Discuss common concerns in care of persons with dementia and nursing responses.

• Develop a nursing care plan for an individual with delirium.

• Develop a nursing care plan for an individual with dementia.

Glossary

Milieu The environment or setting.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

This chapter focuses on cognitive impairment and the diseases that affect cognition. Included in the chapter is a discussion of delirium, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and other dementias. The chapter also presents nursing interventions for people experiencing delirium and dementia as well as caregiving for persons with dementia. Cognitive function in aging is discussed in Chapter 6 and cognitive screening instruments in Chapter 7.

Cognitive impairment

Cognitive impairment (CI) is a term that describes a range of disturbances in cognitive functioning, including disturbances in memory, orientation, attention, and concentration. Other disturbances of cognition may affect intelligence, judgment, learning ability, perception, problem solving, psychomotor ability, reaction time, and social intactness. Dementia, delirium, and depression have been called the three Ds of cognitive impairment because they occur frequently in older adults. These important geriatric syndromes are not a normal consequence of aging, although incidence increases with age.

The three D’s

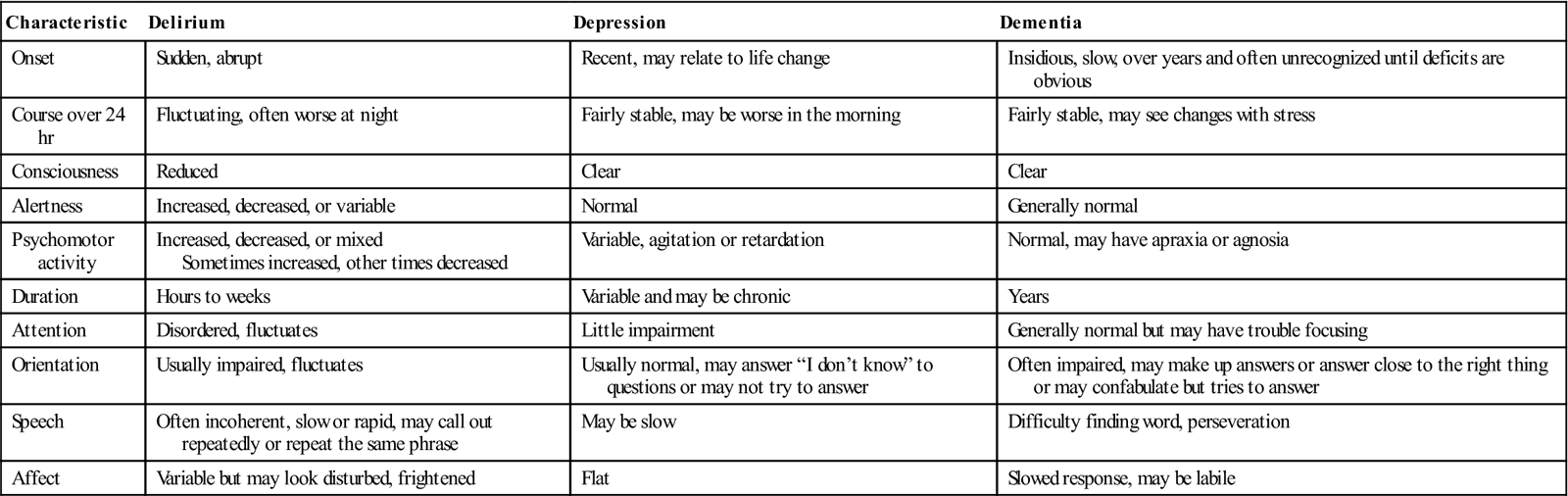

Because cognitive and behavioral changes characterize all three D’s, it can be difficult to diagnose delirium, delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD), or depression. Inability to concentrate, with resulting memory impairment and other cognitive dysfunction, can occur in late-life depression. The term pseudodementia has been used to describe the cognitive impairment that may accompany depression in older adults (see Chapter 22).

Delirium is characterized by an acute or subacute onset, with symptoms developing over a short period of time (usually hours to days). Symptoms tend to fluctuate over the course of the day, often worsening at night. Symptoms include disturbances in consciousness and attention and changes in cognition (memory deficits, perceptual disturbances). Perceptual disturbances are often accompanied by delusional (paranoid) thoughts and behavior. In contrast, dementia typically has a gradual onset and a slow, steady pattern of decline without alterations in consciousness (Voyer et al., 2010).

Dementia, delirium, and depression represent serious pathology and require urgent assessment and intervention (Fletcher, 2012). However, changes in cognitive function in older adults are often seen as “normal” and not investigated. Any change in mental status in an older person requires appropriate assessment. Knowledge about cognitive function in aging and appropriate assessment and evaluation are keys to differentiating these three syndromes. Table 21-1 presents the clinical features and the differences in cognitive and behavioral characteristics in delirium, dementia, and depression.

TABLE 21-1

Differentiating Delirium, Depression, and Dementia

| Characteristic | Delirium | Depression | Dementia |

| Onset | Sudden, abrupt | Recent, may relate to life change | Insidious, slow, over years and often unrecognized until deficits are obvious |

| Course over 24 hr | Fluctuating, often worse at night | Fairly stable, may be worse in the morning | Fairly stable, may see changes with stress |

| Consciousness | Reduced | Clear | Clear |

| Alertness | Increased, decreased, or variable | Normal | Generally normal |

| Psychomotor activity | Increased, decreased, or mixed Sometimes increased, other times decreased | Variable, agitation or retardation | Normal, may have apraxia or agnosia |

| Duration | Hours to weeks | Variable and may be chronic | Years |

| Attention | Disordered, fluctuates | Little impairment | Generally normal but may have trouble focusing |

| Orientation | Usually impaired, fluctuates | Usually normal, may answer “I don’t know” to questions or may not try to answer | Often impaired, may make up answers or answer close to the right thing or may confabulate but tries to answer |

| Speech | Often incoherent, slow or rapid, may call out repeatedly or repeat the same phrase | May be slow | Difficulty finding word, perseveration |

| Affect | Variable but may look disturbed, frightened | Flat | Slowed response, may be labile |

Modified from Sendelbach S, Guthrie PF, Schoenfelder DP: Acute confusion/delirium, J Gerontol Nurs 35 (11):11-18, 2009.

Cognitive assessment

An older person with a change in cognitive function needs a thorough assessment to identify the presence of specific pathological conditions as well as to rule out potentially reversible causes of cognitive impairment. Screening is used to determine if cognitive impairment exists, but basic screening methods do not diagnose specific pathological conditions. If impairment is identified through screening, the person should be referred for a more comprehensive evaluation to confirm a diagnosis of dementia, delirium, or depression, or some other health problem (Braes et al., 2008).

A comprehensive evaluation includes a complete assessment, including laboratory workup, to rule out any medical causes of cognitive impairment. Formal cognitive testing, neuropsychological examination, screening for depression and delirium, interview (family and patient), observation, and functional assessment are additional components of a comprehensive assessment. Computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and an electroencephalogram (EEG) may be indicated in the diagnostic process. Several evidence-based guidelines are available for assessment of changes in mental status and diagnosis of dementia (www.guidelines.gov), and Fletcher (2012) presents a “Nursing Standard of Practice Protocol: Recognition and Management of Dementia.”

Considerations in cognitive assessment

Most older adults worry about developing memory problems or getting AD. Cognitive testing or poor performance on tests of memory is often the cause of great anxiety. Too often, assessments are done when a person is not wearing hearing aids or glasses, or he or she is rushed through a series of questions in a noisy, distracting environment without any preparation or explanation.

It is important to attend to these concerns by establishing rapport and developing a therapeutic relationship, ensuring comfort, accommodating for physical impairments such as hearing and vision loss, creating an environment free of distractions, and putting the person in the best environment to ensure that performance is truly reflective of ability. The challenge is to stress the importance of the assessment without creating undue anxiety. Timing is also important, and cognitive assessments should not be conducted immediately upon awakening from sleep, or immediately before and after meals or medical diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (Braes et al., 2008). It is wise to remember that what seems to be a routine procedure to health professionals can be very intimidating for an older person, especially one who is ill or frail.

Delirium

Etiology

The development of delirium is a result of complex interactions among multiple causes. Delirium results from the interaction of predisposing factors (e.g., vulnerability on the part of the individual due to predisposing conditions, such as cognitive impairment, severe illness, and sensory impairment) and precipitating factors/insults (e.g., medications, procedures, restraints, iatrogenic events). Although a single factor, such as an infection, can trigger an episode of delirium, several coexisting factors are also likely to be present. A highly vulnerable older individual requires a lesser amount of precipitating factors to develop delirium (Inouye et al., 1999; Voyer et al., 2010).

The exact pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development and progression of delirium remain uncertain, and further research is needed to understand its neuropathogenesis. Delirium is thought to be related to disturbances in the neurotransmitters in the brain that modulate the control of cognitive function, behavior, and mood. The causes of delirium are potentially reversible; therefore accurate assessment and diagnosis are critical. Delirium is given many labels: acute confusional state, acute brain syndrome, confusion, reversible dementia, metabolic encephalopathy, and toxic psychosis. The correct terminology is delirium.

Incidence and prevalence

Delirium is a prevalent and serious disorder that occurs in elders across the continuum of care. Estimates are that delirium may affect up to 42% of hospitalized older adults and as many as 87% of older adults in intensive care units (ICUs) (Marcantonio et al., 2010; Sweeny et al., 2008). Older people who have undergone surgery and those with dementia are particularly vulnerable to delirium. The prevalence of delirium is as high as 65% after orthopedic surgery, particularly hip fracture repair (Rigney, 2006). Among older people experiencing cardiac surgery, as many as 20% to 25% experience delirium, affecting even those without any documented preoperative cognitive impairments (Clarke et al., 2010). A 16% delirium rate in patients newly admitted to subacute care has been reported (Marcantonio et al., 2010).

The incidence of DSD ranges from 22% to 89% (Tullmann et al., 2008). Older patients with dementia are three to five times more likely to develop delirium, and it is less likely to be recognized and treated than is delirium without dementia. DSD is associated with high mortality among hospitalized older people (Bellelli et al., 2008). Changes in the mental status of older people with dementia are often attributed to underlying dementia, or “sundowning,” and not investigated. This is particularly significant because about 25% of all older hospitalized patients may have AD or another dementia (Voelker, 2008). Delirium can accelerate the trajectory of cognitive decline in individuals with AD. Despite its prevalence, DSD has not been well investigated, and there are only a few relevant studies in either the hospital or community setting.

Recognition of delirium

Delirium is a medical emergency and one of the most significant geriatric syndromes (Waszynski & Petrovic, 2008). However, it is often not recognized by physicians or nurses. Studies indicate that delirium is unrecognized in 66% to 84% of patients (Pisani et al., 2006; Balas et al., 2007). A comprehensive review of the literature suggested that “nurses are missing key symptoms of delirium and appear to be doing superficial mental status assessments” (Steis & Fick, 2008, p. 47). Cognitive changes in older people are often labeled confusion by nurses and physicians, are frequently accepted as part of normal aging, and are rarely questioned. Confusion in a child or younger adult would be recognized as a medical emergency, but confusion in older adults may be accepted as a natural occurrence, “part of the older person’s personality” (Dahlke & Phinney, 2008, p. 46).

Factors contributing to the lack of recognition of delirium among health care professionals include inadequate education about delirium, a lack of formal assessment methods, a view that delirium is not as essential to the patient’s well-being in light of more serious medical problems, and ageist attitudes (Kuehn, 2010a; Waszynski & Petrovic, 2008). Failure to recognize delirium, identify the underlying causes, and implement timely interventions contributes to the negative sequelae associated with the condition (Tullmann et al., 2008; Kuehn, 2010a). Clearly, education and attitudes about older people must be addressed if we want to improve care outcomes for the growing number of older adults who will need care.

Risk factors for delirium

The risk of delirium increases with the number of risk factors present. Identification of high-risk patients, risk factors, prompt and appropriate assessment, and continued surveillance are the cornerstones of delirium prevention. More than 35 potential risk factors have been identified for delirium. Among the most predictive are immobility, functional deficits, use of restraints or catheters, medications, acute illness, infections, alcohol or drug abuse, sensory impairments, malnutrition, dehydration, respiratory insufficiency, surgery, and cognitive impairment. Unrelieved or inadequately treated pain significantly increases the risk of delirium (Irving & Foreman, 2006). Medications account for 22% to 39% of all delirium, and all medications, particularly those with anticholinergic effects and any new medications, should be considered suspect. Invasive equipment, such as nasogastric tubes, intravenous (IV) lines, catheters, and restraints, also contribute to delirium by interfering with normal feedback mechanisms of the body (Box 21-1).

Clinical subtypes of delirium

Delirium is categorized according to the level of alertness and psychomotor activity. The clinical subtypes are hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed. Box 21-2 presents the characteristics of each of these clinical subtypes. In non-ICU settings, approximately 30% of delirium is hyperactive, 24% hypoactive, and 46% is mixed. Because of the increased severity of illness and the use of psychoactive medications, hypoactive delirium may be more prevalent in the ICU. Although the negative consequences of hyperactive delirium are serious, the hypoactive subtype may be missed more often and is associated with a worse prognosis because of the development of complications such as aspiration, pulmonary embolism, pressure ulcers, and pneumonia. Increased hospital stays, longer duration of delirium, and higher mortality have been associated with hypoactive delirium.

Consequences of delirium

Delirium has serious consequences and is a “high priority nursing challenge for all nurses who care for older adults” (Tullmann et al., 2008, p. 113). Delirium results in significant distress for the patient, his or her family and significant others, and nurses. Delirium is associated with increased length of hospital stay and hospital readmissions, increased services after discharge, and increased morbidity, mortality, and institutionalization, independent of age, coexisting illnesses, or illness severity (Witlox et al., 2010).

Recent research indicates that older adults are vulnerable to the development of accelerated cognitive decline irrespective of the severity of their illness or the length of their hospital stay, making accurate cognitive assessment and prevention and treatment of delirium a priority (Wilson et al., 2012). Delirium is also associated with lasting cognitive impairment and psychiatric problems that may persist after discharge and interfere with the ability to manage chronic conditions (Cole & McCusker, 2009; Hain et al., 2012; Lindquist et al., 2011). Screening all older adults before they leave the hospital may help to identify those in need of specific transitional care (see Chapter 3) with more frequent follow-up after hospitalization (Lindquist et al., 2011). Further research is needed to determine the reasons for the long-term poor outcomes, whether characteristics of the delirium itself (subtype or duration) influence prognosis, and how the long-term effects might be decreased.

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

Assessment

Several instruments can be used to assess the presence and severity of delirium. To detect changes, it is very important to determine the person’s usual mental status. If the person cannot tell you this, family members or other caregivers who are with the patient can be asked to provide this information. If the patient is alone, the responsible party or the institution transferring the patient can provide this information by phone. Do not assume the person’s current mental status represents his or her usual state, and do not attribute altered mental status to age alone or assume that dementia is present. All older patients, regardless of their current cognitive function, should have a formal assessment to identify possible delirium when admitted to the hospital (see the Evidence-Based Practice box).

The Mini-Mental State Examination, 2nd Edition (MMSE-2) is considered a general test of cognitive status that helps identify mental status impairment. Although the MMSE-2 alone is not adequate for diagnosing delirium, it represents a brief, standardized method to assess mental status and can provide a baseline from which to track changes (see Chapter 7). Several delirium-specific assessment instruments are available, such as the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Inouye et al., 1990), NEECHAM Confusion Scale (Neelon et al., 1996), and the CAM-ICU (Ely et al., 2001), an instrument specifically designed to assess delirium in an intensive care population.

Assessment using the MMSE-2, CAM, and NEECHAM should be conducted on admission to the hospital, throughout the hospitalization for all patients identified at risk for delirium, and for all patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of delirium or develop additional risk factors (Steis & Fick, 2008). Results of a study (Waszynski & Petrovic, 2008) suggested that the CAM was useful in identifying delirium in hospitalized adults, and nurses found it very helpful in identifying changes in cognitive functioning. As a result of these findings, the CAM was made a customary part of the daily flow sheet.

When a patient is identified as having delirium, reassessment should be conducted every shift. Documenting specific objective indicators of alterations in mental status rather than using the global, nonspecific term confusion will lead to more appropriate prevention, detection, and management of delirium and its negative consequences. Findings from assessment using a validated instrument are combined with nursing observation, chart review, and physiological findings. Delirium often has a fluctuating course and can be difficult to recognize, so assessment must be ongoing and include multiple data sources.

Interventions

Nonpharmacological

Intervention begins with prevention. An awareness and identification of the risk factors for delirium and a formal assessment of mental status are the first-line interventions for prevention. Because the etiology of delirium is multifactorial, “for an intervention strategy to be effective, it should target the multifactorial origins of delirium with multicomponent interventions that address more than one risk factor” (Rosenbloom-Brunton et al., 2010, p. 23). Multidisciplinary approaches to prevention of delirium seem to show the most promising results, but continued research is needed to evaluate what type of approach has the most beneficial effect in specific clinical settings.

A well-researched multidisciplinary program of delirium prevention in the acute care setting, the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) (Inouye et al., 1999; Bradley et al., 2005; Rubin et al., 2006), focuses on managing six risk factors for delirium: cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual impairments, hearing impairments, and dehydration. The program is used in more than 60 hospitals in the United States and internationally. Patient outcomes with the use of this model include a 40% reduction in the incidence of delirium, a 67% reduction in rates of functional decline, and significant cost savings in both hospitals and long-term care facilities. Most of the interventions can be considered quite simple and part of good nursing care.

Examples of interventions in the HELP program include the following: offering herbal tea or warm milk instead of sleeping medications, keeping the ward quiet at night by using vibrating beepers instead of paging systems, using silent pill crushers, removing catheters and other devices that hamper movement as soon as possible, encouraging mobilization, assessing and managing pain, and correcting hearing and vision deficits. Fall risk reduction interventions, such as bed and chair alarms, low beds, reclining chairs, volunteers to sit with restless patients, and keeping routines as normal as possible with consistent caregivers, are other examples of interventions.

The Family-HELP program, an adaptation and extension of the original HELP program, trains family caregivers in selected protocols (e.g., orientation, therapeutic activities, vision and hearing). Initial research demonstrates that active engagement of family caregivers in preventive interventions for delirium is feasible and supports a culture of family-oriented care (Rosenbloom-Brunton et al., 2010). Further information on HELP can be found at http://www.hospitalelderlifeprogram.org/public/public-main.php. Box 21-3 presents suggested interventions for delirium.

A commonly used intervention for patients with delirium in acute care is the use of “sitters” or “constant observers” (COs). Costs associated with this practice can be very high, and data indicate that the use of COs does not consistently decrease the incidence of unsafe patient behavior in the patient with delirium. Nor do they assist in identifying causes of delirium or identifying appropriate interventions (Sweeny et al., 2008). More effective and less costly interventions for patients with delirium include programs of fall risk–reduction strategies, assessment of delirium using the CAM, and protocols for intervention.

Pharmacological

Pharmacological interventions to treat the symptoms of delirium may be necessary if patients are in danger of harming themselves or others, or if nonpharmacological interventions are not effective. However, pharmacological interventions should not replace thoughtful and careful evaluation and management of the underlying causes of delirium. Pharmacological treatment should be one approach in a multicomponent program of prevention and treatment. Research on the pharmacological management of delirium is limited, but it has been suggested that “with increased understanding of the neuropathogenesis of delirium, drug therapy could become primary to the treatment of delirium” (Irving & Foreman, 2006, p. 122). A few studies have suggested that use of dexmedetomidine as a sedative or analgesic may reduce the incidence or duration of delirium (Kuehn, 2010b).

Ozbolt and colleagues (2008) conducted a literature review of the use of antipsychotics for treatment of delirious elders and concluded that the atypical antipsychotics demonstrate similar rates of efficacy to haloperidol for the treatment of delirium and have a lower rate of extrapyramidal side effects. Further research is needed since no double-blind placebo trials exist. Short-acting benzodiazepines are often used to control agitation but may worsen mental status. Psychoactive medications, if used, should be given at the lowest effective dose, monitored closely, and reduced or eliminated as soon as possible so that recovery can be assessed.

Caring for patients with delirium can be a challenging experience. Patients with delirium can be difficult to communicate with, and disturbing behaviors such as pulling out IV lines or attempting to get out of bed disrupt medical treatment and compromise safety. It is important for nurses to realize that behavior is an attempt to communicate something and express needs. The patient with delirium feels frightened and out of control. The calmer and more reassuring the nurse is, the safer the patient will feel. Box 21-4 presents some communication strategies that are helpful in caring for people experiencing delirium.

Dementia

In contrast to delirium, dementia is an irreversible state that progresses over years and causes memory impairment and loss of other intellectual abilities severe enough to cause interference with daily life. Degenerative dementias include AD, Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and frontotemporal lobe dementias (FTDs). AD accounts for 50% to 70% of all dementia cases. Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) encompasses several syndromes: vascular dementia; mixed primary neurodegenerative disease and vascular dementia; and cognitive impairment of vascular origin that does not meet the dementia criteria. Increasing evidence suggests that most dementias have neurodegenerative (most commonly AD) and vascular features, and these seem to act synergistically (Desai et al., 2010).

Other less commonly occurring dementias are Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) (subacute spongiform encephalopathy) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–related dementia. Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) causes a dementia characterized by ataxic gait, incontinence, and memory impairment. This disease is reversible and treated with a shunt that diverts cerebrospinal fluid away from the brain (Table 21-2).

TABLE 21-2

Types of Dementia and Typical Characteristics

| Type of Dementia | Characteristics |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | Most common type of dementia, accounting for 60%-80% of cases. Hallmark abnormalities are deposits of the protein fragment beta-amyloid (plaques) and twisted strands of the protein tau (tangles). Difficulty remembering names and recent events, difficulty expressing oneself with words, spatial cognition problems, and impaired reasoning and judgment, apathy, depression are often early symptoms. Language disturbances may also be a presenting symptom. Later symptoms include impaired judgment, disorientation, behavior changes, and difficulty speaking, swallowing, and walking. |

| Vascular dementia, also known as multi-infarct or post-stroke dementia or vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) | Second most common type of dementia. Impairment is caused by decreased blood flow to parts of the brain due to a series of small strokes that block arteries. Symptoms often overlap with AD although memory may not be as seriously affected. |

| Mixed dementia | Characterized by the hallmark abnormalities of AD and another type of dementia, most commonly vascular dementia but also other types such as dementia with Lewy bodies. Mixed dementia is more common than previously thought. Neurodegenerative changes occur along with vascular changes. |

| Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) | Later onset of dementia, at least 1 year after onset of parkinsonian features. Hallmark abnormality is Lewy bodies (abnormal deposits of the protein alpha-synuclein) that forms inside the nerve cells of the brain. |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | Pattern of decline similar to AD including problems wih memory and judgment as well as behavior changes. Alertness and severity of cognitive symptoms may fluctuate daily. Visual hallucinations, muscle rigidity, and tremors are common. Exhibit a sensitivity to neuroleptic drugs, so these medications should be avoided. |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and vCJD (transmissible spongiform encephalopathy) | A rapidly fatal and rare form of dementia characterized by tiny holes that give the brain a “spongy” appearance under microscope. May be hereditary, occur sporadically, or be transmitted from infected individuals. Failing memory, behavioral changes, lack of coordination, visual disturbances. vCJD (bovine spongiform encephalopathy/mad cow disease) occurs in younger patients and may be caused by contaminated feed. |

| Frontotemporal dementia | Involves damage to brain cells, especially in the front and side regions of the brain. Symptoms include change in personality and behavior and difficulty with language. Pick’s disease, characterized by Pick’s bodies in the brain, is one form of frontotemporal dementia. |

| Normal-pressure hydrocephalus | Caused by buildup of fluid in the brain without corresponding increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure. Symptoms include difficulty walking (ataxic gait), memory loss, incontinence. Can sometimes be corrected with surgical installation of a shunt to drain excess fluid. |

Data from Alzheimer’s Association: 2010 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures, Alzheimer Dement 6(2):158-194, 2010.

Different types of dementia have different symptom patterns and distinguishing microscopic brain abnormalities. The symptoms of dementia also overlap and can be further complicated by comorbid medical conditions. Accurate diagnosis is important, since treatment and prognosis vary. The rate of diagnosis of dementia is quite low despite advances in technology and knowledge about the different types and causes of dementia. In some studies, as many as 75% of patients with moderate to severe dementia and more than 95% of those with mild impairment escape diagnosis in the primary care setting. Clearly, education of both professionals and the community is needed so that more timely diagnosis and treatment can be initiated (Stefanacci, 2008). The diagnosis of dementia is complex, and it is essential that older people with symptoms of cognitive impairment receive specialized assessment to determine the causes so that treatment can be tailored appropriately.

Incidence and prevalence

Dementia is one of the most disabling and burdensome of chronic health conditions. The growing worldwide epidemic of dementia has frightening implications for the health of older people and their families as well as the health and societal costs associated with the disease. Healthy People 2020 has added a new topic on dementia with the goal of reducing the morbidity and costs associated with the condition and of maintaining and enhancing the quality of life for persons with dementia, including AD (see the Healthy People box) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). The cost of care for someone with dementia is three times more than for those who do not have the disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012).

Alzheimer’s disease

AD, the most common form of dementia, was first described by Dr. Alois Alzheimer in 1906. In the United States, about 5.4 million people 65 years of age and older and 200,000 individuals younger than 65 years of age have AD. Of Americans 65 years of age and over, 1 in 8 has Alzheimer’s; nearly half of people 85 years of age and older have the disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). If current trends continue, by the year 2050, the prevalence of AD is expected to quadruple unless medical breakthroughs identify ways to prevent or more effectively treat the disease. AD is the sixth leading cause of death and the nation’s third most expensive medical condition.

Unless something is done, the care cost of AD and other dementias is projected to be $1.1 trillion by 2050. These costs include a 600% increase in Medicare costs and a 400% increase in Medicaid costs. One factor contributing to the soaring cost projections is that nearly half of the individuals with AD would be in the later stages of the disease when more expensive around-the-clock care is often necessary (Alzheimer’s Association, 2010). Although the ultimate goal is to discover a treatment that can prevent or cure AD, even modest improvements in treatment can have a huge impact.

Types of alheimer’s disease

AD is characterized by the development of neuronal intracellular neurofibrillary tangles consisting of the protein tau and extracellular deposits of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in fibril structures, the loss of connections between nerve cells in the brain, and the death of these nerve cells. These changes in the brain develop slowly over many years of pathology accumulation. At the same time, some people have the brain changes associated with AD and yet do not show symptoms of dementia.

AD has two types: early-onset dementia (EO-D) and late-onset dementia. EO-D is a rare form, affecting only about 5% of all people who have AD. It develops between 30 and 60 years of age. This form of AD can result from gene mutations on chromosomes 21, 14, and 1, and each of these mutations causes abnormal proteins to be formed. These mutations cause an increased amount of beta-amyloid protein, the major component of AD plaques, to be formed (National Institute on Aging [NIA], 2010).

The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern means that offspring in the same generation have a 50/50 chance of developing EO-D if one of their parents had it. Even if only one of these mutated genes is inherited from a parent, the person will almost always develop EO-D. Predictive genetic testing, with appropriate precounseling and postcounseling, may be offered to at-risk individuals with an apparent autosomal dominant inheritance of AD (Desai et al., 2010).

Most cases of AD are the late-onset form, developing after 60 years of age. The mutations seen in EO-D are not involved in this form of the disease. This disorder does not clearly run in families, and late-onset AD is probably related to variations in one or more genes in combination with lifestyle and environmental factors. The apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, found on chromosome 19, has been extensively studied as a risk factor, and a particular variant of this gene, the e4 allele, seems to increase a person’s risk for developing late-onset AD.

The inheritance pattern of late-onset AD is uncertain. People who inherit one copy of the APOE e4 allele have an increased risk of developing the disease; those who inherit two copies are at even greater risk. However, not all people with AD have the e4 allele, and not all people who have the e4 allele will develop the disease. A blood test is available that can identify which APOE alleles a person has, but screening for APOE e4 in asymptomatic individuals in the general population is not recommended. Using an approach called a genome-wide association study, four to seven other AD risk-factor genes have been identified (Desai et al., 2010; NIA, 2010).

Research

The focus of research on AD is on the interaction between risk-factor genes and lifestyle or environmental factors. Increasing evidence strongly points to the potential risk roles of vascular risk factors (VRFs) and disorders (e.g., midlife obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, cigarette smoking, obstructive sleep apnea, diabetes, and cerebrovascular lesions) and the potential protective roles of psychosocial factors (e.g., higher education, regular exercise, healthy diet, intellectually challenging leisure activity, and active socially integrated lifestyle) in the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of dementia (especially AD and VCI). Head trauma is also considered a risk factor (Table 21-3) (Ghetu et al., 2010). Addressing modifiable risk factors throughout life may delay or decrease the risks of developing dementias such as AD. “Prevention is the wave of the future in the dementia arena” (Kamat et al., 2010, p. 20).

TABLE 21-3

Risk Factors and Protective Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease: Potential Mechanisms

| Factor | Risk | Potential Mechanisms |

| Advanced age | Increased risk | Possible decreased brain reserves |

| Sex | Females have increased risk | Living longer and loss of neuroprotective effects of estrogen |

| Family history | Increased risk | APP, presenilin-1, presenilin-2 mutations may result in oversecretion of amyloid-β (Aβ) in familial AD. APOE e4 allele increases risk of sporadic (late-onset) AD |

| Depression | Increased risk | May decrease brain reserves/transmitters |

| High-fat and cholesterol diet | Increased risk | Increased neuroinflammation; possible increased substrate for APP |

| CRP | Increased risk | Increased neuroinflammation |

| Homocysteine | Increased risk | Increased oxidative stress, free radical toxicity, increased atherosclerotic sequelae |

| Smoking | Increased risk | Accelerated cerebral atrophy, perfusional decline, and white matter lesions |

| Diabetes mellitus | Increased risk | Impaired glucose uptake in neuronal cells, decreased blood supply due to small-vessel disease |

| Hyperlipidemia | Increased risk | Increased Aβ accumulation |

| Genetic | Increased risk | Mutations of presenilin-1, presenilin-2, APP |

| Hypertension | Increased risk | Decreased cerebral blood flow/cerebral ischemia, white matter lesions |

| Head trauma | Increased risk | Not fully understood—possible blood-brain barrier disruption |

| Obesity | Increased risk | Hyperlipidemia and hypertension and via their mechanisms described earlier |

| Mediterranean diet | Decreased risk | Decreased neuroinflammation, decreased oxidative stress, decreased Aβ42 toxicity |

| Increased education | Decreased risk | Education may increase neural connections |

| Increased mental activity | Decreased risk | Cognitive reserve model in which people cope better and can generate more neurons during their lifetime |

| Increased physical activity | Decreased risk | Increased cerebral blood flow, increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APP, amyloid precursor protein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

From Kamat S, Kamat A, Grossberg G: Dementia risk prediction: are we there yet? Clin Geriatr Med 26:113-123, 2010.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree