Analysis in Naturalistic Inquiry

Key terms

Categories

Constant comparative method

Credibility

Interpretation

Saturation

Taxonomy

Theme

Triangulation (crystallization)

Truth value

We now turn our attention to the way in which researchers approach the analysis of data in naturalistic inquiry. As you probably surmise at this point, the action process of conducting analyses in naturalistic inquiry is quite different from the actions taken during statistical decision making in experimental-type research. Analysis in naturalistic research is a dynamic and iterative process. Also, as noted in Chapter 18, keep in mind that organizing information in naturalistic inquiry is an analytical action, and it is difficult to separate organization and management actions from analytical actions.

Although all analytical strategies reflect a logical approach, there is no step-by-step, recipe-like set of rules that can be followed by an investigator in naturalistic inquiry. Many organizational and analytical strategies can be used at different points in the process. The analytical process also depends on the type of data that are collected, and it will vary depending on whether the data are narrative, observational, visual, musical, diaries, or other data formats.

After you read this chapter, you may want to refer to other literature sources to obtain more in-depth and specific understanding of particular analytical approaches in naturalistic inquiry.1–4 Here we provide a full introduction to and overview of the basic principles that underlie the general thinking and action processes of researchers involved in various forms of analysis across the traditions of naturalistic inquiry.

Strategies and stages in naturalistic analysis

Many purposes inform the analytical process in naturalistic inquiry. The selection of a particular approach to analysis depends on the primary purpose of the research study, the scope of the query, and the particular design. Table 20-1 summarizes the basic purpose and analytical approach used by seven designs in naturalistic inquiry.

TABLE 20-1

Purpose and Analytical Strategy of Naturalistic Study Designs

| Study Design | Main Purpose | Basic Analytical Strategy |

| Endogenous | Varies | Varies |

| Participatory action research | Varies | Varies |

| Phenomenology | Identifies essence of personal experiences | Groups statements based on meaning; develops textual description |

| Heuristic | Discovers personal experiences | Describes meaning of experience for researcher and others |

| Life history | Provides biographical account | Describes chronological events; identifies turning points |

| Ethnography | Describes and explains cultural patterns | Identifies themes and develops interpretive schema |

| Grounded theory | Constructs or modifies theory | Provides constant comparative method to name and frame theoretical constructs and relationships |

Some analytical strategies in naturalistic inquiry are extremely unstructured and interpretive, such as in phenomenology, heuristic approaches, and some ethnographic studies. Other analytical strategies are highly structured, as in grounded theory. Still other types of naturalistic inquiry may incorporate numerical descriptions and may vary in the type of analysis used, as in certain forms of ethnography, endogenous approaches, and participatory action research. Further, some forms of naturalistic inquiry are highly interpretive but use a specific analytical strategy, such as in life history. In this type of study, the investigator searches for “epiphanies,” or key turning points, in the life of the individual(s) under study, using a chronological or biographical account as the basis from which interpretations are derived. Each analytical approach provides a different understanding of the phenomenon under study and reveals a distinct aspect of field experience. Furthermore, in any given study, a researcher may use a combination of analytical strategies at different points in the course of fieldwork.

Therefore, you would need to use three analytical approaches in this study. Each approach would reflect a specific purpose and yield a particular understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The findings from each approach would then be integrated to contribute to a comprehensive and integrative understanding of the initial research query (e.g., “What is the experience and meaning of living in assisted living?”).

Although each type of naturalistic design uses a different analytical strategy, the basic process across any type of naturalistic design can essentially be conceptualized as occurring in two overlapping and interrelated stages. The first stage of analysis occurs at the exact moment the investigator enters the virtual, conceptual, or physical field. It involves the attempt to make immediate sense of what is being observed and heard, or what is referred to as “learning the ropes.”2 At this stage the purpose of analysis is primarily descriptive and yields “hunches” or initial interpretations that guide data collection decisions made in the field. The second stage follows the conclusion of fieldwork and involves a more formal review and analysis of all the information that has been collected. The investigator refines or evolves an interpretation that is recorded in a written report for dissemination to the scientific community.

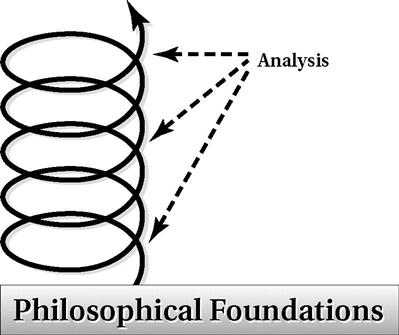

At each stage, the researcher may use a different analytical approach. The actions during each stage are best conceptualized as a “spiral” in which each loop of the spiral involves a set of analytical tasks that lead to the next loop in successive fashion until a complete understanding of the field or phenomenon under study is derived.

Stage one: analysis in the field

As shown in previous chapters, the process of naturalistic inquiry is iterative. Let us examine what this means in the initial analytical stage. First, data analysis occurs immediately as the researcher enters the field, and analysis continues throughout the investigator’s engagement in the field. Analysis is the basis from which all subsequent field decisions are made: who to interview, what to observe, and which piece of information to explore further. Data collection efforts are inextricably connected to the initial impressions and hunches that are formulated by the investigator; that is, an observation, or datum, gives rise to an initial understanding of the phenomenon under study. This initial understanding informs or shapes the next data collection decision. Each collection-analytical action builds successively on the previous action.

Thus, during fieldwork, the researcher begins the process of systematically examining data—field notes, recorded observations, and transcriptions of interviews—to obtain initial descriptions, impressions, and hunches. It is important to note that transcriptions are usually completed immediately or shortly after the completion of an interview or observation to enable the investigator to evaluate the data and make subsequent field decisions to further the data collection efforts. The investigator also keeps careful records of his or her perceptions, biases, or opinions and begins to group information into meaningful categories that describe the phenomenon of interest. This descriptive analysis is especially critical in the early stages of fieldwork. It is essential to the process of reframing the initial query and setting limits or boundaries as to who and what should be investigated.

This initial set of analytical steps involves four interrelated thinking and action processes (Box 20-1). Keep in mind that these interrelated thinking and action processes are dynamic. That is, the four processes are not neat, separate steps or entities that occur in sequence at a particular time in fieldwork. Rather, they are ongoing, overlapping processes that lead to refinement of interpretations throughout the data-gathering effort.

Investigators, particularly those new to this type of inquiry, may feel overwhelmed and initially lost in this process. The sheer quantity of information generated in a short time can also make the investigator feel inundated. However, these feelings are a natural part of the experience of conducting naturalistic inquiry. The researcher must be able to feel comfortable with being in “limbo” at first, that is, not knowing the whole story and letting it unfold.

Engaging in Thinking Process

Naturalistic inquiry is based on either an inductive or an abductive thinking process (see Chapter 1). This thinking process is key to all the analytical approaches of naturalistic inquiry. One of the first analytical efforts of the researcher is to engage in a thoughtful process. This may seem basic to any research endeavor, but the active engagement of the investigator in thinking about each datum in naturalistic inquiry assumes a different quality and level of importance than in other research endeavors. David Fetterman described this basic analytical effort in ethnographic research as follows:

The best guide through the thickets of analysis is at once the most obvious and most complex of strategies: clear thinking. First and foremost, analysis is a test of the ethnographer’s ability to process information in a meaningful and useful manner.5

More specifically, an inductive and abductive thinking process is characterized by the development of an initial organizational system and the review of each datum. The organizational system must emerge from the data. The investigator must avoid imposing constructs or theoretical propositions before becoming involved with the data. For example, in the case of data collected through an interview, the researcher will read and reread the transcriptions. From these initial readings, ideas and hunches will be formulated. In a phenomenological, heuristic, or life history approach, the investigator will continue working inductively until all meanings of an experience are explicated.

In an abductive approach, the thinking process begins inductively with an idea. The investigator explores information or behavioral actions and formulates a working hypothesis, which is examined in the context of the field to see whether it fits. The investigator works somewhat deductively to draw implications from the working hypothesis as a way of verifying its accuracy. This process characterizes the actions of the investigator throughout the field experience, especially for grounded theory6 and ethnography.7

In ethnography, Fetterman labeled this process “contextualization,” or the placement of data into a larger perspective.5 While in the field, the investigator continually strives to place each piece of data into a context to understand the “bigger picture” or how the parts fit together to make the whole. One way the investigator strives to understand how a datum fits into the larger context is by grouping information into categories.

Developing Categories

A voluminous amount of information is gathered within a short period in the course of fieldwork. The researcher will feel the need to manage the immense amount of data collected so quickly. Consider when you have had to review a large body of literature for a course in college. Perhaps you first went to the library to obtain information from the literature. You probably realized that your notes from the readings soon became overwhelming and that you needed to develop some organization to make sense of the information you gathered. The same principle applies in the initial stages of analysis in naturalistic inquiry. The researcher must find a way to organize analytically and make sense of the information as it is being collected.

One of the first meaningful ways in which the investigator begins to organize information is to develop categories, or “affinities.” We prefer the term categories for clarity and word recognition. Northcutt and McCoy8 noted the similarities between categories and variables, indicating that categories are single phenomena that can be named and in which multiple elements must occur. This action process represents a major step in naturalistic analysis. How do categories emerge? As Wax described:

The student begins “outside” the interaction, confronting behaviors he finds bewildering and inexplicable: the actors are oriented to a world of meanings that the observer does not grasp … and then gradually he comes to be able to categorize peoples (or relationships) and events.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assume you are conducting a microethnographic study of the meaning of daily life in an assisted-living facility for elder residents. You decide to use several data collection strategies, such as interviewing residents and family members, observing daily activities, and video-recording staff interactions with residents. The initial purpose of your analysis is to describe daily routines and behaviors of the residents. One analytical strategy may involve counting the number of activities in which residents are engaged, then grouping activities by the categories they represent (e.g., self-care, leisure, social). Another purpose of the analysis is to identify themes that explain the meanings attributed by residents to their daily life in the facility. Analysis will involve an interpretive process to identify statements that reflect core meanings of the experience of assisted living. On the basis of these two analytical steps, suppose you discover that staff relationships are a salient factor in the experiences of residents. To better understand this particular finding, you may add another analytical strategy, such as frame-by-frame video analysis of staff–resident verbal interactions.

Assume you are conducting a microethnographic study of the meaning of daily life in an assisted-living facility for elder residents. You decide to use several data collection strategies, such as interviewing residents and family members, observing daily activities, and video-recording staff interactions with residents. The initial purpose of your analysis is to describe daily routines and behaviors of the residents. One analytical strategy may involve counting the number of activities in which residents are engaged, then grouping activities by the categories they represent (e.g., self-care, leisure, social). Another purpose of the analysis is to identify themes that explain the meanings attributed by residents to their daily life in the facility. Analysis will involve an interpretive process to identify statements that reflect core meanings of the experience of assisted living. On the basis of these two analytical steps, suppose you discover that staff relationships are a salient factor in the experiences of residents. To better understand this particular finding, you may add another analytical strategy, such as frame-by-frame video analysis of staff–resident verbal interactions.