Setting the Boundaries of a Study

Key terms

Adequacy

Appropriateness

Boundary setting

External validity

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Informants

Participants locations, conceptual boundaries, virtual boundaries

Respondents

Subjects

Assume that you have a research problem and an appropriate design that matches your research purpose and question or query. You are now ready to consider how individuals, concepts, or locations will be selected for your study and how particular

phenomena will be defined and identified. Selecting research participants, whether they are human or not, and identifying concepts and phenomena represent one of the first action processes that set or establish the boundaries or limitations of a study.

Setting boundaries is inextricably linked to important ethical considerations, such as how people are selected for study participation, how they are informed of study procedures, how the information they share is managed and treated confidentially, and to whom or what the study results are applied. Because of the significance of the ethical component of boundary setting, we examine this in depth in Chapter 12.

Why set boundaries to a study?

Setting limits or boundaries as to what and who will be in a study is an action that occurs in every type of research design, whether in the experimental-type or the naturalistic tradition. A researcher sets boundaries that limit the scope of the investigation to a specified group of individuals, phenomena, geography, or set of conceptual dimensions. The following example helps show why it is important to set boundaries or limitations.

Studies are also necessarily limited or bounded by identifying particular data collection strategies and concepts that will be considered.

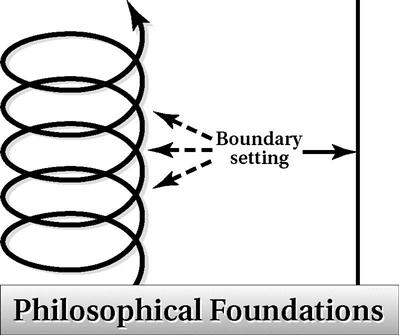

There are numerous ways to limit the scope of a study. As discussed in previous chapters on the thinking processes of research, an investigator actively bounds a study on the basis of five interrelated considerations (Box 11-1).

Your philosophical approach or the particular research tradition you are using to develop your study will set the backdrop from which all action decisions will be made. A deductive, experimental-type study tightly bounds the study to preidentified concepts and a highly specified population. The purpose of the study, the particular research question, and the design will also shape the extent to which concepts, phenomena, and populations are delimited.

For example, an intervention study that tests the effectiveness of a particular home care service in producing a specified outcome must carefully match the intent of the intervention with specific characteristics of the subject group or individuals who will be targeted and recruited for the study. Thus, identifying highly specified criteria as to who is eligible and who is not eligible to participate is a required action process. These criteria are referred to as “inclusion and exclusion criteria,” as discussed later.

On the other hand, a broad inquiry designed to investigate the experiences of persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) may set few restrictions except diagnostic condition as to who can participate in the study and thus cast a wide net for participant enrollment. An investigator might even delimit a study by virtual location such as a listserv or virtual chat room for persons with AIDS.

Finally, your ability to access the population of interest or the phenomenon to be studied is another consideration as to how a study is bounded. Limited resources, such as monetary and time restrictions, will likely yield a study design that is tightly delimited or bounded.

Thus, there are both practical and theoretical considerations in how researchers bound the context of either an experimental-type or a naturalistic form of inquiry. In practical terms, it would be impossible to observe every speech event, personal interaction, image, or activity in a particular natural setting. You must bound the study by making purposeful selections as to what will be observed and who will be interviewed.1,2

In experimental-type designs, boundary setting is a process that must occur before entering the field or beginning the study. Boundaries are set in three ways: (1) specifying the concepts that will be operationally defined, (2) establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria that define the population that will be studied, and (3) developing a sampling plan.

This set of action processes in naturalistic designs differs from those in the experimental-type tradition. Naturalistic boundary setting may occur throughout the research endeavor depending on how the dynamic design unfolds. Initial boundaries are set by the investigator through defining the particular domain of interest and the point of access from which to enter that domain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Consider a study that uses a survey design to describe the health and social service needs of “parents of children with intellectual impairments.” It would be impossible to interview every person who falls into this category in the United States. As the researcher, you need to make some decisions as to who you should specifically interview and how. One consideration may be to limit the survey to one or more particular geographic locations. Another way to limit the study may be to consider only certain types of conditions that fall under the rubric of intellectual impairment. Limiting the number of parents of children with intellectual impairments who are selected for study participation is an example of setting a boundary by restricting the characteristics of the persons who will be studied.

Consider a study that uses a survey design to describe the health and social service needs of “parents of children with intellectual impairments.” It would be impossible to interview every person who falls into this category in the United States. As the researcher, you need to make some decisions as to who you should specifically interview and how. One consideration may be to limit the survey to one or more particular geographic locations. Another way to limit the study may be to consider only certain types of conditions that fall under the rubric of intellectual impairment. Limiting the number of parents of children with intellectual impairments who are selected for study participation is an example of setting a boundary by restricting the characteristics of the persons who will be studied. Assume you are interested in the historical development of your profession. It would not be feasible to examine every historical detail or written document to understand the sociopolitical and health care context of professional growth. In this case, you need to determine criteria for selecting historical documents to examine and identify the key historical events in which professional activity emerged. Deciding which historical documents to examine is an example of limiting your study by specifying the boundaries of the concept and time period that will be explored.

Assume you are interested in the historical development of your profession. It would not be feasible to examine every historical detail or written document to understand the sociopolitical and health care context of professional growth. In this case, you need to determine criteria for selecting historical documents to examine and identify the key historical events in which professional activity emerged. Deciding which historical documents to examine is an example of limiting your study by specifying the boundaries of the concept and time period that will be explored. This domain may be (1) geographic, as in the selection of an urban community in which to study health behaviors of low-income families; (2) a group of individuals, such as the selection of persons with a particular health condition (e.g., stroke, diabetes, traumatic brain injury), living in an identified community; or (3) a particular experience, such as trauma, dialysis, caregiving, pain, or chronic health problems.

This domain may be (1) geographic, as in the selection of an urban community in which to study health behaviors of low-income families; (2) a group of individuals, such as the selection of persons with a particular health condition (e.g., stroke, diabetes, traumatic brain injury), living in an identified community; or (3) a particular experience, such as trauma, dialysis, caregiving, pain, or chronic health problems.