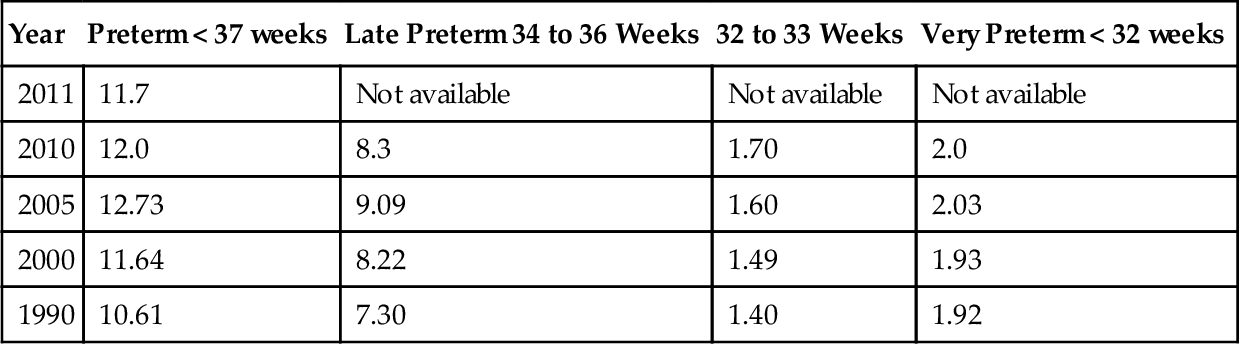

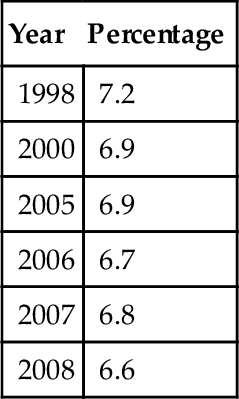

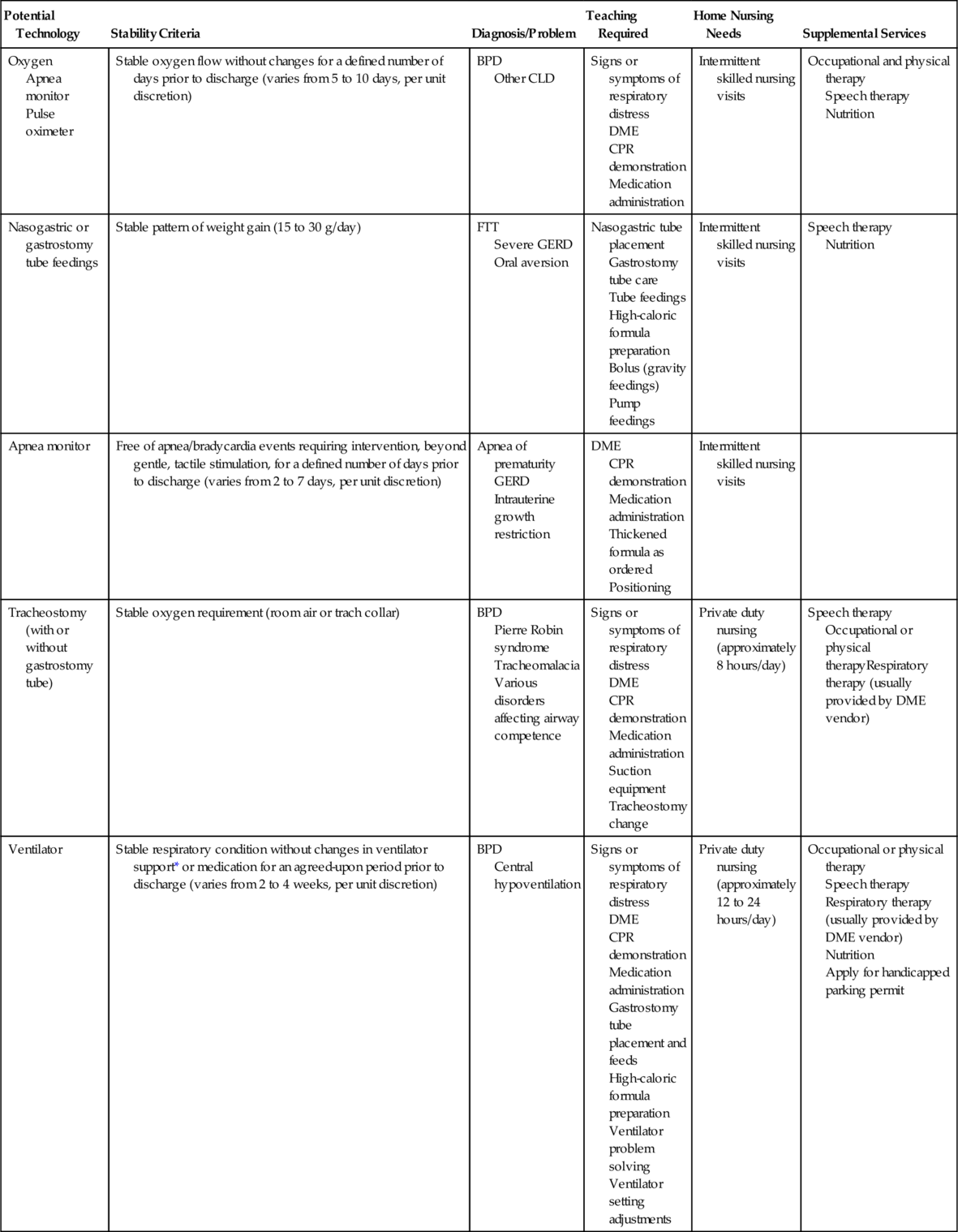

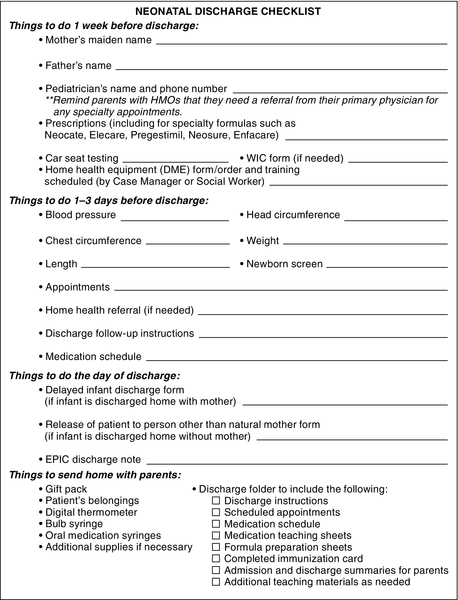

CHAPTER 19 1. Describe current trends in the discharge of the high-risk infant. 2. Identify individualized clinical criteria for discharge. 3. Discuss the role of the family in the discharge of a high-risk infant. 4. Describe discharge planning and the transition-to-home process for the high-risk neonate. 5. Identify discharge teaching needs for parents of a high-risk infant. 6. Identify key components of infant and family care postdischarge. Preterm birth rates have risen more than 20% since 1990. Nearly half a million babies are born preterm each year, and the numbers have risen steadily. The National Center for Health Statistics released final birth data for 2010, revealing that there were 478,790 preterm births; one in eight babies (12% of live births) were born preterm in the United States (Martin et al, 2012). The preterm birth rate peaked at 12.8% in 2006, and fell slightly to 12% in 2010 (Table 19-1). TABLE 19-1 Percentage of Preterm Births: United States, Final 1990, 2000, 2005, and 2010; and Preliminary 2011 Data from National Center for Health Statistics: Final natality data. 2011. Retrieved from www.marchofdimes.com/peristats. ■ 69% are born between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation, and are termed late-preterm births. ■ 14% are born between 32 and 33 weeks of gestation. ■ 17% are born at less than 32 weeks of gestation. The infant mortality rate fell slightly to 6.6 deaths per 1000 live births in 2008, with prematurity the leading cause of death in the first month of life (Table 19-2). TABLE 19-2 Infant Mortality Data from National Center for Health Statistics: Final mortality data, 1990-1994; and Period linked birth/infant death data, 1995-present. 2008. Retrieved from www.marchofdimes.com/peristats. Preterm birth cost the nation more than $26.2 billion in medical and educational costs and lost productivity in 2005. During the same year the average first-year medical costs, including both inpatient and outpatient care, were about 10 times greater for preterm ($32,325) than for term ($3325) infants. Average hospitalization cost between 2001 and 2004 for the moderately preterm infant, born at 32 to 34 weeks, was $31,000 (Kirkby et al., 2007). Many infants are discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) with chronic conditions requiring ongoing medical care and increasing societal burden. Major morbidities tend to be highest in the smallest survivors (< 1000 g at birth) and can include significant lifelong conditions such as cerebral palsy, cognitive delays, and visual or hearing loss (Wilson-Costello, 2007). B. Discharge planning begins on admission to the intensive care nursery and continues throughout the hospitalization. C. An interdisciplinary team of skilled professionals ensures successful transition to home (Box 19-1). D. Parent–infant relationships and family dynamics are altered by emotional and financial stressors. Maternal depression is common and negatively affects the parent–child relationship and infant development (Beck, 2003; Quevedo et al., 2012). E. Parents, as the primary caregivers, must be educated to provide complex care for their infant and be empowered to advocate for their infant, facilitating transition to home and optimizing their child’s health and development. F. The medical home model for delivering primary care is particularly important for children with special health care needs. G. The late preterm infant may have special needs at discharge, requiring vigilant follow-up (Whyte, 2010). A. Medical costs are rising rapidly. 1. The newborn period is a major source of uncompensated care and accounts for a high proportion of catastrophic cost cases, an increasing problem with the increased incidence and survival of premature infants (Kirkby et al., 2007). 2. Economic pressures, including equitable reimbursement for services, and the utilization of costly medical resources, continue to challenge health care systems when caring for the very low birth weight (VLBW, < 1000 g) infant in the hospital and home settings. B. Infants are discharged earlier from the NICU, requiring care of varying complexity, from nasogastric feedings, multiple medications, apnea monitors, and oxygen to ventilators, dialysis, and parenteral nutrition. C. Infants are discharged with special needs on the premise that the home environment, as opposed to the hospital environment, is beneficial for the child and the family, and that health care costs will be decreased (Hummel and Cronin, 2004). D. Early discharge of the VLBW infant can be accomplished in a safe and positive manner, benefiting the infant and family (Sajous et al., 2007a, 2007b; Sturm, 2005). 1. The infant must be physiologically stable before discharge. 2. The parents must be able and willing to care for their infant in the home. 3. Parental education must be complete before discharge, with parents demonstrating competency in the care of the infant. 4. Skilled home nursing care by neonatal nurses contributes to the successful discharge of the high-risk infant. Sajous et al. (2007a, 2007b) describe an integrated neonatal home care program where preterm infants are discharged home safely to transition from nasogastric to oral feedings, and readmission rates were decreased for infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia discharged with supplemental oxygen. E. Discharge planning includes the role of the case managers, whose roles include care coordination, utilization review, insurance reimbursement, and discharge planning. F. Clinical pathways and care maps are effective tools for discharge planning and tracking outcomes. G. The medical home model for delivering primary care is recognized as optimal in the care of the NICU graduate. The American Academy of Pediatrics developed the medical home model for delivering primary care that is accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective to all children and youth, including those with special health care needs. H. NICU design is moving toward private rooms, enhancing family interaction and caregiving, facilitating preparation for discharge. I. Electronic medical records are increasingly used, allowing improved documentation, retrieval, and interdisciplinary communication. J. Evidence-based care is provided in the NICU and home care setting. 2. Additional organizations that publish guidelines for transition of the preterm infant to home include the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 2008); the National Association of Neonatal Nurses (1999); Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses; the March of Dimes; and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. K. Childhood disability is increasing and emotional, behavioral, and neurologic disabilities are now more prevalent than physical impairments. 1. Children and youth with special health care needs are defined by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) of the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration as “those who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, development, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.” This definition is broad and inclusive, and it emphasizes the characteristics held in common by children with a wide range of diagnoses (McPherson et al., 1998). 2. Approximately 10.2 million children in the United States, which represents 15% of all U.S. children, have special health care needs based on the MCHB definition. 3. More than a fifth of U.S. households with children have at least one child with special needs (Currie and Kahn, 2012). B. The required period of stability before discharge has not been studied or standardized. Controversy and wide variations in practice exist in the apnea- or bradycardia-free length of time that an infant is observed before discharge (Hummel and Cronin, 2004; Zupancic et al., 2003). Discharge of a technology-dependent infant should be anticipated and planned, with the team agreeing on an end point and a stability point for discharge (Hummel and Cronin, 2004). Support should then be maintained and the infant prepared for discharge without changes. C. Assessment of the home and parental capabilities guide a safe discharge. A multitude of factors contribute to the ability of a family to care for a medically complex infant in the home. Parent health, siblings, family support, financial difficulties, home facilities, proximity to health care, transportation options, child care or day care considerations, and other issues may prohibit discharge to the parent’s home. Infant and parent needs must be balanced to achieve a safe discharge. A. Parents need emotional support as they struggle to cope with the ups and downs and uncertainties that accompany parenting an ill newborn (Eiser et al., 2005). Social work, pastoral care, and parent-to-parent support groups may benefit parents and should be tailored to meet the family’s needs. March of Dimes provides parent support online; local chapters may also provide support groups. B. Parenting an infant after discharge from the NICU presents many challenges, including multiple physician appointments, complex infant care, and the uncertainties of the infant’s future (Bakewell-Sachs and Gennaro, 2004; Hummel and Cronin, 2004). Effective interventions to promote mothering the high-risk infant include home nurse visits, skin-to-skin contact, individual infant-focused education and counseling, and theory-based group intervention (Gardner and Deatrick, 2006). C. Postpartum depression is common and exacerbated by mothering a high-risk infant (Beck and Indman, 2005). NICU and home care nurses must remain vigilant, referring mothers for further care when depression is recognized (Beck, 2003, 2008a, 2008b). D. Cultural differences should be considered, as some cultures may expect that the infant stay in the hospital until the special needs are resolved. E. The family is the constant in the infant’s life and should be an active participant in care, starting at admission. Continuing parental education involves assessment of knowledge and readiness to learn. Most parents desire an understanding of their infant’s disease process and status. Caregivers should assist parents in learning their infant’s behaviors and providing individualized care based on the responses (Cook et al., 2012; Heermann et al., 2005; Kleberg et al., 2007; Meijssen et al., 2011; Vandenberg, 2007; Westrup, 2007). Parents learn about parenting by observing caregivers and actively participating in their infant’s care. F. Assessment of parental knowledge base and previous infant care experience contributes to an individualized teaching plan, established weeks prior to anticipated discharge. Family educational, social, emotional, and financial needs must be assessed; discharge plans are individualized according to these needs (Giebe, 2007). 2. Learning experiences can be offered through hands-on care, demonstration of specific care practices, and verbal reinforcement. Information can be obtained from a variety of sources, including individual demonstration, group teaching sessions with other parents, published teaching tools, videos, written materials, and Internet resources. G. Parents are active participants in care conferences and involved in discharge planning. H. Parents should contact and meet a health care provider in the community and make follow-up appointments prior to the infant’s discharge from the hospital. The case manager, social worker, discharge coordinator, staff registered nurse, or advanced practice nurse can assist with the process. The health care provider should be capable of providing a medical home for the infant with special health care needs. I. Parents should be provided an opportunity to care for their infant in an overnight/transition room prior to discharge. This is particularly important when the care is complex or questions remain regarding parental capabilities in caring for the infant. A. Discharge planning begins at birth or when the infant’s condition is no longer critical. 1. A long-term view of the infant’s hospitalization is essential to discharge planning. 2. A care map may assist in this process by cueing the team at specific intervals to plan for discharge. 3. See Table 19-3 for planning for discharge with technology, related to complex medical issues. TABLE 19-3 Planning for Discharge With Technology BPD, Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CLD, chronic lung disease; DME, durable medical equipment; FTT, failure to thrive; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. * Using a ventilator approved for in-home use. B. Discharge teaching should begin weeks prior to the projected discharge date. 1. Discharge education and home transition plans should be clearly outlined (Fig. 19-1). 2. Planning should include a timeline to complete parent education and all steps necessary for home transition. 3. Written information regarding the infant’s care should be provided, particularly with complex discharges (Menghini, 2005). C. Family members are active participants in the home transition plan. Parents should participate in infant care from birth and are essential team members in the care of their infant. D. Discharge planning and the transition-to-home process require a multidisciplinary approach. Consistency in care providers is critical. Parents should be empowered to make decisions about their infant’s care and discharge. The case manager, discharge planner, primary nurse, and social worker often coordinate the discharge process. E. Intermittent care conferences with the family throughout hospitalization ensure open communication, facilitating a smooth transition to home. These can be formalized, including all team members, or simplified to include the parents and a few key team members. F. A comprehensive discharge-focused care conference should be completed several weeks prior to discharge. 1. Parents are encouraged to bring a list of questions and needs to the conference. 2. All community providers should be invited to participate in the discharge care conference. If key personnel are unable to attend this conference, contact should be made to ensure that the practitioner is willing to care for the infant, and to communicate ongoing health issues and needs. 3. Criteria for discharge are discussed and the teaching plan is reviewed. The anticipated course of recovery and ongoing problems are outlined, and the home care/durable medical equipment needs are discussed. 4. Strategies to prevent rehospitalization are discussed (Smith et al., 2004). G. A comprehensive discharge summary, including resolved and ongoing problems, is given to the family on discharge, and sent to postdischarge caregivers. See Box 19-3 for a list of information to be included in the summary. An electronic summary and information can be provided on a disc or flash drive for computerized use.

Discharge Planning and Transition to Home Care

INTRODUCTION

Year

Preterm < 37 weeks

Late Preterm 34 to 36 Weeks

32 to 33 Weeks

Very Preterm < 32 weeks

2011

11.7

Not available

Not available

Not available

2010

12.0

8.3

1.70

2.0

2005

12.73

9.09

1.60

2.03

2000

11.64

8.22

1.49

1.93

1990

10.61

7.30

1.40

1.92

Year

Percentage

1998

7.2

2000

6.9

2005

6.9

2006

6.7

2007

6.8

2008

6.6

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

HEALTH CARE TRENDS

DISCHARGE CRITERIA MUST BE ESTABLISHED AND INDIVIDUALIZED TO THE INFANT AND FAMILY (BOX 19-2)

PARENTAL NEEDS AND ROLE IN THE DISCHARGE AND TRANSITION-TO-HOME PROCESS

DISCHARGE PLANNING AND TRANSITION TO HOME

Potential Technology

Stability Criteria

Diagnosis/Problem

Teaching Required

Home Nursing Needs

Supplemental Services

Oxygen

Apnea monitor

Pulse oximeter

Stable oxygen flow without changes for a defined number of days prior to discharge (varies from 5 to 10 days, per unit discretion)

BPD

Other CLD

Signs or symptoms of respiratory distress

DME

CPR demonstration

Medication administration

Intermittent skilled nursing visits

Occupational and physical therapy

Speech therapy

Nutrition

Nasogastric or gastrostomy tube feedings

Stable pattern of weight gain (15 to 30 g/day)

FTT

Severe GERD

Oral aversion

Nasogastric tube placement

Gastrostomy tube care

Tube feedings

High-caloric formula preparation

Bolus (gravity feedings)

Pump feedings

Intermittent skilled nursing visits

Speech therapy

Nutrition

Apnea monitor

Free of apnea/bradycardia events requiring intervention, beyond gentle, tactile stimulation, for a defined number of days prior to discharge (varies from 2 to 7 days, per unit discretion)

Apnea of prematurity

GERD

Intrauterine growth restriction

DME

CPR demonstration

Medication administration

Thickened formula as ordered

Positioning

Intermittent skilled nursing visits

Tracheostomy (with or without gastrostomy tube)

Stable oxygen requirement (room air or trach collar)

BPD

Pierre Robin syndrome

Tracheomalacia

Various disorders affecting airway competence

Signs or symptoms of respiratory distress

DME

CPR demonstration

Medication administration

Suction equipment

Tracheostomy change

Private duty nursing (approximately 8 hours/day)

Speech therapyOccupational or physical therapyRespiratory therapy (usually provided by DME vendor)

Ventilator

Stable respiratory condition without changes in ventilator support* or medication for an agreed-upon period prior to discharge (varies from 2 to 4 weeks, per unit discretion)

BPD

Central hypoventilation

Signs or symptoms of respiratory distress

DME

CPR demonstration

Medication administration

Gastrostomy tube placement and feeds

High-caloric formula preparation

Ventilator problem solving

Ventilator setting adjustments

Private duty nursing (approximately 12 to 24 hours/day)

Occupational or physical therapy

Speech therapy

Respiratory therapy (usually provided by DME vendor)

Nutrition

Apply for handicapped parking permit

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree