The Preschool Child

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. List the major developmental tasks of the preschool-age child.

4. Discuss the development of positive bedtime habits.

5. Discuss one method of introducing the concept of death to a preschool child.

7. Discuss the characteristics of a good preschool.

8. Discuss the value of play in the life of a preschool child.

9. Designate two toys suitable for the preschool child, and provide the rationale for each choice.

10. Describe the speech development of the preschool child.

11. Discuss the value of the following: time-out periods, consistency, role modeling, and rewards.

14. Explain the use of therapeutic play with a handicapped child.

Key Terms

animism (p. 421)

art therapy (p. 432)

artificialism (p. 421)

associative play (p. 425)

centering (p. 421)

echolalia (ĕk-ō-LĀ-lē-ă, p. 422)

egocentrism (p. 421)

enuresis (ĕn-yū-RĒ-sĭs, p. 428)

modeling (p. 427)

parallel play (p. 425)

play therapy (p. 432)

preconceptual stage (p. 421)

preoperational phase (p. 421)

symbolic functioning (p. 421)

therapeutic play (p. 432)

time-out (p. 427)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

General Characteristics

The child from age 3 to 5 years is often referred to as the preschool child. This period is marked by slowing of the physical growth process and mastery and refinement of the motor, social, and cognitive abilities that will enable the child to be successful in his or her school years.

The major tasks of the preschool child include preparation to enter school, development of a cooperative type of play, control of body functions, acceptance of separation, and increase in communication skills, memory, and attention span.

Physical Development

The infant who tripled his or her birth weight at 1 year has only doubled the 1-year weight by 5 years of age. For instance, the infant who weighs 9 kg (20 lb) on the first birthday will probably weigh about 18 kg (40 lb) by the fifth birthday. The child between 3 and 6 years of age grows taller and loses the chubbiness seen during the toddler period. Between 3 and 5 years of age, there will be an increase of 7.6 cm (3 inches) in height, mostly in the legs, that contributes to the development of an erect, slender appearance. Visual acuity is 20/40 at 3 years of age and 20/30 at 4 years of age. The achievement of 20/20 vision may be accomplished by school age. All 20 primary teeth have erupted. Hand preference develops by 3 years of age, and efforts to change a left-handed child to a right-handed child can cause a high level of frustration. Appetite fluctuates widely. The normal pulse rate is 90 to 110 beats/min. The rate of respirations during relaxation is about 20 breaths/min. The systolic blood pressure is about 85 to 90 mm Hg, and the diastolic blood pressure is about 60 mm Hg.

Preschool children have good control of their muscles and participate in vigorous play; they become more adept at using already familiar skills as each year passes. They can swing and jump higher. Their gait resembles that of an adult. They are quicker and have more self-confidence than they did as toddlers.

Cognitive Development

The thinking of the preschool child is unique. Piaget calls this period the preoperational phase. It comprises children from 2 to 7 years of age and is divided into two stages: the preconceptual stage (2 to 4 years of age) and the intuitive thought stage (4 to 7 years of age). Of importance in the preconceptual stage is the increasing development of language and symbolic functioning. Symbolic functioning is seen in the play of children who pretend that an empty box is a fort; they create a mental image to stand for something that is not there.

Another characteristic of this period is egocentrism, a type of thinking in which children have difficulty seeing any point of view other than their own. Because children’s knowledge and understanding are restricted to their own limited experiences, misconceptions arise. One misconception is animism. This is a tendency to attribute life to inanimate objects. Another is artificialism, the idea that the world and everything in it is created by people.

The intuitive stage is one of prelogical thinking. Experience and logic are based on outside appearance (the child does not understand that a wide glass and a tall glass can both contain 4 oz of juice). A distinctive characteristic of intuitive thinking is centering, the tendency to concentrate on a single outstanding characteristic of an object while excluding its other features.

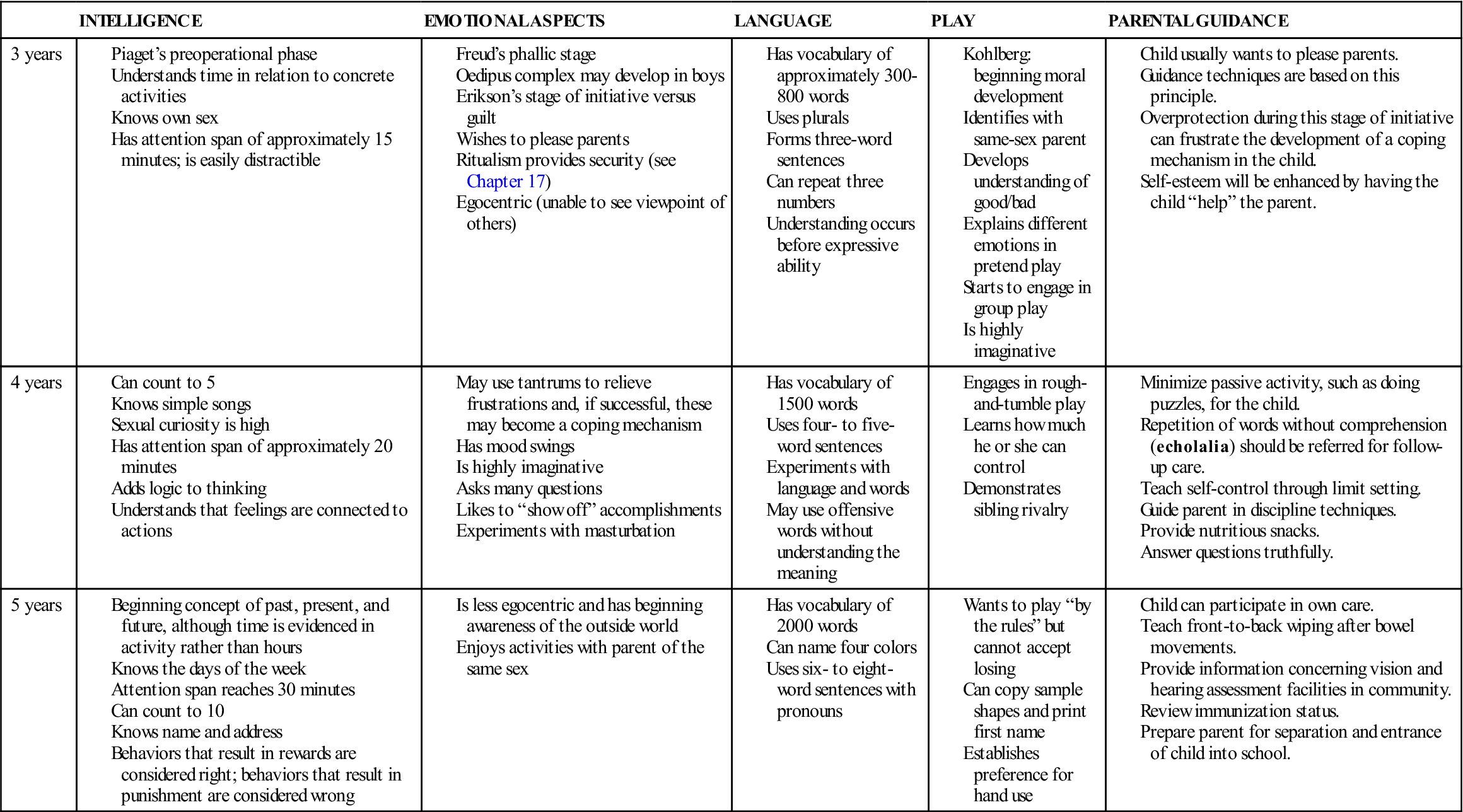

More mature conceptual awareness is established with time and experience. This process is highly complex, and the implications for practical application are numerous. Interested students are encouraged to explore these concepts through further study. Table 18-1 summarizes some major theories of personality development for the preschooler.

Table 18-1

Preschool Growth and Development

| INTELLIGENCE | EMOTIONAL ASPECTS | LANGUAGE | PLAY | PARENTAL GUIDANCE | |

| 3 years | |||||

| 4 years | |||||

| 5 years |

Effects of Cultural Practices

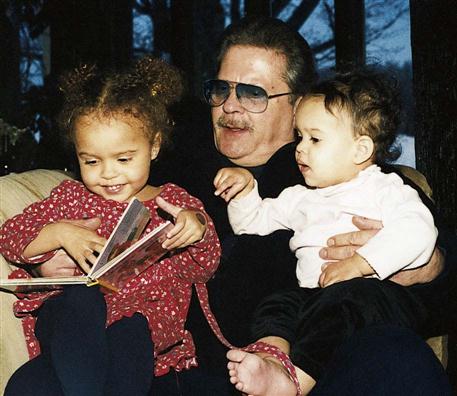

Cultural practices can influence the development of a sense of initiative in families who practice authoritarian types of parenting styles that put a great value on obedience and conformity. Parents and older siblings are models for language development, and the mastery of sounds proceeds in the same order around the world. Some parents speak both English and a native language in the home. Studies have shown that young children adapt quickly to a bilingual environment and cultural practices (Figure 18-1). Cultural preferences related to dietary practices are discussed in Chapter 15.

Language Development

The development of language as a communication skill is essential for success in school (Figure 18-2). Delays or problems in language expression can be caused by physiological, psychological, or environmental stressors. Typically, in the preschool period between 2 and 5 years of age, the number of words in the child’s sentence should equal the child’s age (e.g., two words at 2 years of age). By  years of age, most children evidence possessiveness (my doll). By 4 years of age they can use the past tense, and by 5 years of age they can use the future tense. The development of language skills includes both the understanding of language and the expressing of oneself in language. Children who have difficulty expressing themselves in words often exhibit tantrums and other acting-out behaviors.

years of age, most children evidence possessiveness (my doll). By 4 years of age they can use the past tense, and by 5 years of age they can use the future tense. The development of language skills includes both the understanding of language and the expressing of oneself in language. Children who have difficulty expressing themselves in words often exhibit tantrums and other acting-out behaviors.

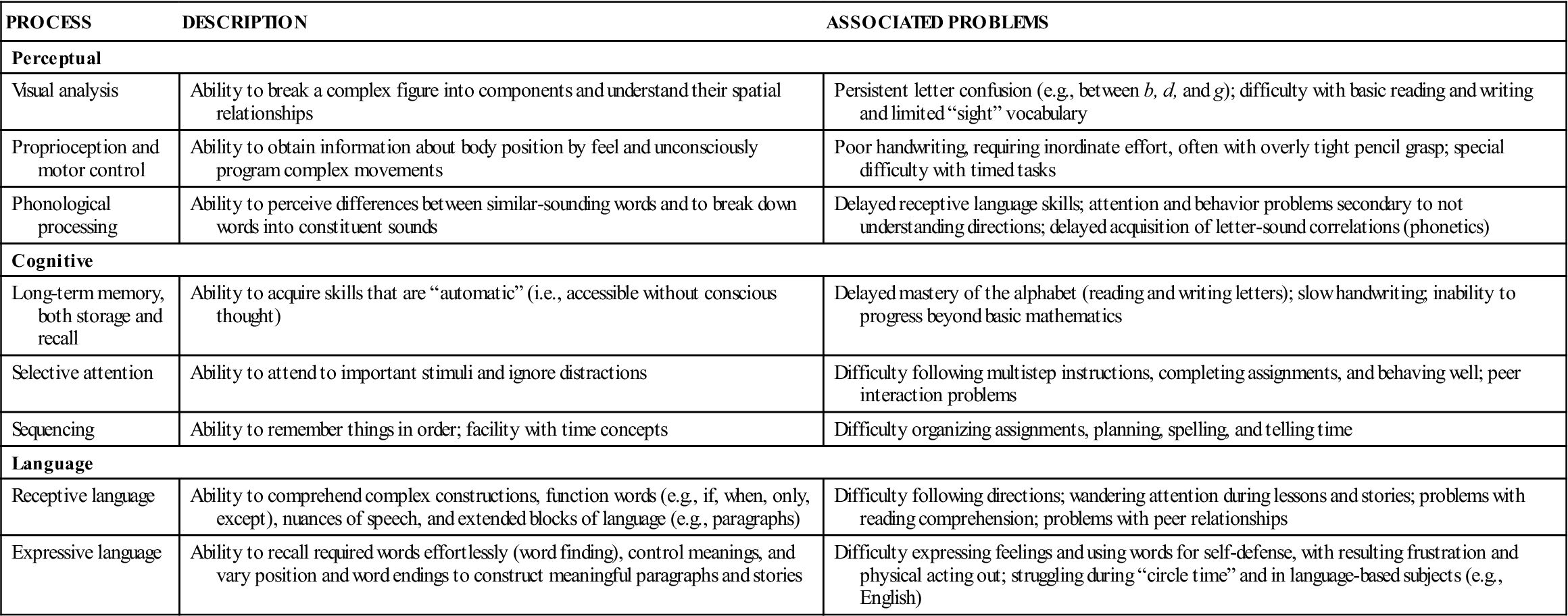

Table 18-2 lists the language, cognitive, and perceptual abilities required for success in school. Problems detected and treated during the preschool years can prevent many school problems in later years. Table 18-3 on p. 424 describes the clinical symptoms of typical language disorders. Evaluation of language development must be done together with an assessment of problem-solving skills.

Table 18-2

Selected Perceptual, Cognitive, and Language Processes Required for Elementary School Success

| PROCESS | DESCRIPTION | ASSOCIATED PROBLEMS |

| Perceptual | ||

| Visual analysis | Ability to break a complex figure into components and understand their spatial relationships | Persistent letter confusion (e.g., between b, d, and g); difficulty with basic reading and writing and limited “sight” vocabulary |

| Proprioception and motor control | Ability to obtain information about body position by feel and unconsciously program complex movements | Poor handwriting, requiring inordinate effort, often with overly tight pencil grasp; special difficulty with timed tasks |

| Phonological processing | Ability to perceive differences between similar-sounding words and to break down words into constituent sounds | Delayed receptive language skills; attention and behavior problems secondary to not understanding directions; delayed acquisition of letter-sound correlations (phonetics) |

| Cognitive | ||

| Long-term memory, both storage and recall | Ability to acquire skills that are “automatic” (i.e., accessible without conscious thought) | Delayed mastery of the alphabet (reading and writing letters); slow handwriting; inability to progress beyond basic mathematics |

| Selective attention | Ability to attend to important stimuli and ignore distractions | Difficulty following multistep instructions, completing assignments, and behaving well; peer interaction problems |

| Sequencing | Ability to remember things in order; facility with time concepts | Difficulty organizing assignments, planning, spelling, and telling time |

| Language | ||

| Receptive language | Ability to comprehend complex constructions, function words (e.g., if, when, only, except), nuances of speech, and extended blocks of language (e.g., paragraphs) | Difficulty following directions; wandering attention during lessons and stories; problems with reading comprehension; problems with peer relationships |

| Expressive language | Ability to recall required words effortlessly (word finding), control meanings, and vary position and word endings to construct meaningful paragraphs and stories | Difficulty expressing feelings and using words for self-defense, with resulting frustration and physical acting out; struggling during “circle time” and in language-based subjects (e.g., English) |

From Kliegman, R., Behrman, R., Jenson, H.B., & Stanton, B. (2007). Nelson’s textbook of pediatrics (18th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders.

Table 18-3

Not Talking: A Clinical Classification

| WHEN PARENTS SAY | CLASSIFY THE SYMPTOMS AS |

| “I’m the only one who understands what she says.” | Articulation disorder |

| “She’ll do what I say, but when she wants something, she just points.” | Expressive language delay |

| “He can’t play ‘show me your nose,’ and the only word he says is ‘mama.’ ” | Global language delay |

| “He never made those funny baby sounds or said ‘mama’ and ‘dada,’ and now he just repeats everything I say.” | Language disorder |

| “He used to say things like ‘Joey go bye-bye,’ but now he doesn’t talk at all.” | Language loss |

From Montgomery, T. (1994). When children do not talk. Contemporary Pediatrics, 11(9), 49.

Development of Play

Play activities in the preschool child increase in complexity. At 2 to 3 years of age, the child imitates the activities of daily living of the parents (hammering, shaving, feeding the doll). By 4 years of age, the child may develop broader themes such as a trip to the zoo. By 5 years of age, a trip to the moon demonstrates the child’s imaginary abilities. Play enables the child to experience multiple roles and emotional outlets, such as the aggressor, the victim, the superpower, or the acquisition of toys or friends they desire. Appealing to the child’s magical thinking is the best approach to communication.

Spiritual Development

Preschoolers learn about religious beliefs and practices from what they observe in the home. Preschoolers cannot yet understand abstract concepts; their concept of God, sometimes treated as an imaginary friend, is concrete. Preschool children can memorize Bible stories and related rituals, but their understanding of the concepts is limited. Observing religious traditions practiced in the home during a period of hospitalization (e.g., before-meal or bedtime prayers) can help the preschool child deal with stressors.

Sexual Curiosity

When guiding parents concerning the sexual education of young children, the nurse should use the following common principles of teaching and learning:

Preschool children are as matter-of-fact about sexual investigation as they are about any other learning experience and are easily distracted to other activities. Sexual curiosity displayed in the form of masturbation or “playing doctor” should be approached in a positive manner. The appropriate touch or dress can be taught without generating a “bad” or “dirty” concept of the activity. Teaching socially acceptable behavior must be in the form of guidance rather than discipline.

Masturbation

Masturbation is common in both genders during the preschool years. The child experiences pleasurable sensations, which lead to a repetition of the behavior. It is beneficial to rule out other causes of this activity, such as rashes or penile or vaginal irritation. Masturbation in the preschool child is considered harmless if the child is outgoing, sociable, and not preoccupied with the activity.

Education of the parents consists of assuring them that this behavior is a form of sexual curiosity and is normal and not harmful to the child, who is merely curious about sexuality. The cultural and moral background of the family must be considered in assessing the degree of discomfort about this experience. A history of the time and place of masturbation and the parental response is helpful. Punitive reactions are discouraged. Parents are advised to ignore the behavior and distract the child with some other activity. The child should know that masturbation is not acceptable in public, but this must be explained in a nonthreatening manner. Children who masturbate excessively and who have experienced a great deal of disruption in their lives benefit from ongoing counseling.

Bedtime Habits

The development and reinforcement of optimal bedtime habits are important in the preschool years. Parents should be guided to engage the child in quiet activities before bedtime, to maintain specific rituals that signal bedtime readiness (such as storytelling), and to verbally state “after this story, it will be bedtime.” The use of a night-light, a favorite bedtime toy, or a glass of water at the bedside is an option. Attention-getting behavior that results in taking the child into the parent’s bed should be discouraged because it rewards the attention-getting behavior and defeats the objectives of the bedtime ritual. The nurse should be aware that specific cultures encourage “family beds,” where children regularly sleep with siblings and parents. Understanding cultural practices is essential before preparing a teaching plan.

Physical, Mental, Emotional, and Social Development

The Three-Year-Old

Three-year-olds are a delight to their parents. They are helpful and can assist in simple household chores. They obtain articles when directed and return them to the proper place. Three-year-olds come very close to the ideal picture that parents have in mind of their child. They are living proof that their parents’ guidance during the trying 2-year-old period has been rewarded. Temper tantrums are less frequent, and in general the 3-year-old is less erratic. They are still individuals, but they seem better able to direct their primitive instincts than previously. They can help to dress and undress themselves, use the toilet, and wash their hands. They eat independently, and their table manners have improved.

Three-year-olds talk in longer sentences and can express thoughts and ask questions. They are more company to their parents and other adults because they can talk about their experiences. They are imaginative, talk to their toys, and imitate what they see about them. Soon they begin to make friends outside the immediate family. Parallel play (playing independently within a group) and associative play are both typical of this period. Children play in loosely associated groups. Because they can now converse with playmates, they find satisfaction in joining their activities. Three-year-olds play cooperatively for short periods. They can ask others to “come out and play.” If 3-year-olds are placed in a strange situation with children they do not know, they commonly revert to parallel play because it is more comfortable.

Preschoolers begin to find enjoyment away from Mom and Dad, although they want them nearby when needed. They begin to lose some of their interest in their mother, who up to this time has been more or less their total world. The father’s prestige begins to increase. Romantic attachment to the parent of the opposite sex is seen during this period. A daughter wants “to marry Daddy” when she grows up. Children also begin to identify themselves with the parent of the same sex.

Preschool children have more fears than the infant or older child because of increased intelligence (which enables them to recognize potential dangers), memory development, and graded independence (which brings them into contact with many new situations). Toddlers are not afraid of walking in the street because they do not understand its danger. Preschool children realize that trucks can injure, and they worry about crossing the street. This fear is well-founded, but many others are not.

The fear of bodily harm, particularly the loss of body parts, is unique to this stage. The little boy who discovers that his infant sister is made differently may worry that she has been injured. He wonders if this will happen to him. Masturbation is common during this stage as children attempt to reassure themselves that they are all right. Other common fears include fear of animals, fear of the dark, and fear of strangers. Night wandering is typical of this age-group.

Preschool children become angry when others attempt to take their possessions. They grab, slap, and hang onto them for dear life. They become very distraught if toys do not work the way they should. They resent being disturbed from play. They are sensitive, and their feelings are easily hurt. Much of the unpleasant social behavior seen during this time is normal and necessary to the child’s total pattern of development.

The Four-Year-Old

Four-year-olds are more aggressive and like to show off newly refined motor skills. They are eager to let others know they are superior, and they are prone to pick on playmates. Four-year-olds are boisterous, tattle on others, and may begin to swear if they are around children or adults who use profanity. They recount personal family activities with amazing recall but forget where their tricycle has been left. At this age, children become interested in how old they are and want to know the exact age of each playmate. It bolsters their ego to know that they are older than someone else in the group. They also become interested in the relationship of one person to another, such as Timmy is a brother but is also Daddy’s son.

Four-year-olds can use scissors with success. They can lace their shoes. Their vocabulary has increased to about 1500 words. They run simple errands and can play with others for longer periods. Many feats are done for a purpose. For instance, they no longer run just for the sake of running. Instead, they run to get someplace or see something. They are imaginative and like to pretend they are doctors or firefighters. They begin to prefer playing with friends of the same sex.

The preschool child enjoys simple toys and common objects. Raw materials are more appealing than toys that are ready-made and complete in themselves. An old cardboard box that can be moved about and climbed into is more fun than a dollhouse with tiny furniture. A box of sand or colored pebbles can be made into roads and mountains. Parents should avoid showering their children with ready-made toys. Instead, they can select materials that are absorbing and that stimulate the child’s imagination.

Stories that interest young children depict their daily experiences. If the story has a simple plot, it must be related to what they understand to hold their interest. They also enjoy music they can march around to, music videos, and simple instruments they can shake or bang. (Make up a song about their daily life, and watch their reaction.)

The Concept of Death

Children between 3 and 4 years of age begin to wonder about death and dying. They may pretend to be the hero who shoots the intruder dead, or they may actually witness a situation in which an animal is killed. Their questions are direct. “What is ‘dead’? Will I die?” The view of the family is important to the interpretation of this complex phenomenon.

Children may become acquainted with death through objects with no particular significance to them. For instance, the flower dies at the end of the summer and does not bloom anymore. It no longer needs sunshine or water because it is not alive. Usually young children realize that others die, but they do not relate death to themselves. If they continue to pursue the question of whether or not they will die, parents should be casual and reassure them that people do not generally die until they have lived a long and happy life. Of course, as they grow older they will discover that sometimes children do die.

The underlying idea is to encourage questions as they appear and gradually help them accept the truth without undue fear. There are many excellent books for children about death. Two that are appropriate for the preschool child are Geranium Mornings by S. Powell and My Grandpa Died Today by J. Fassler. The dying child is discussed in Chapter 27.

The Five-Year-Old

Five is a comfortable age. Children are more responsible, enjoy doing what is expected of them, have more patience, and like to finish what they have started. Five-year-olds are serious about what they can and cannot do. They talk constantly and are inquisitive about their environment. They want to do things correctly and seek answers to their questions from those whom they consider to “know” the answers. Five-year-old children can play games governed by rules. They are less fearful because they believe their environment is controlled by authorities. Their worries are less profound than at an earlier age.

The physical growth of 5-year-olds is not outstanding. Their height may increase by 5 to 7.6 cm (2 to 3 inches), and they may gain 1.4 to 2.7 kg (3 to 6 lb). They may begin to lose their deciduous teeth at this time. They can run and play games simultaneously, jump three or four steps at once, and tell a penny from a nickel or a dime. They can name the days of the week and understand what a weeklong vacation is. They usually can print their first name.

Five-year-olds can ride a tricycle around the playground with speed and dexterity. They can use a hammer to pound nails. Adults should encourage them to develop motor skills and not continually remind them to “be careful.” The practice children experience will enable them to compete with others during the school-age period and will increase confidence in their own abilities. As at any age, children should not be scorned for failure to meet adult standards. Overdirection by solicitous adults is damaging. Children must learn to do tasks themselves for the experience to be satisfying.

The number and type of television or computer programs that parents allow the preschool child to watch is a topic for discussion. Although children enjoyed television at age 3 or 4 years, it was usually for short periods. They could not understand much of what was occurring. The 5-year-old, however, has better comprehension and may want to spend a great deal of time watching television or playing computer games. The plan of management differs with each family. Whatever is decided must be discussed with the child. For example, television and computers should not be allowed to interfere with good health habits, sleep, meals, and physical activity. Most parents find that children do not insist on watching television if there is something better to do.

Guidance

Discipline and Limit Setting

Much has been written on the subject of discipline, views of which have changed considerably over time. Today, authorities place much importance on the development of a continuous, warm relationship between children and their parents. They believe this helps to prevent many problems. The following is a brief discussion that may help the nurse in guiding parents.

Children need limits for their behavior. Setting limits makes them feel secure, protects them from danger, and relieves them from making decisions that they may be too young to formulate. Children who are taught acceptable behavior have more friends and develop good self-esteem. They live more enjoyably within the neighborhood and society. The manner in which discipline or limit setting is carried out varies from culture to culture. It also varies among different socioeconomic groups. Individual differences occur among families and between parents and vary according to the characteristics of each child.

The purpose of discipline is to teach and to gradually shift control from parents to the child, that is, to develop self-discipline or self-control. Positive reinforcement for appropriate behavior has been cited as more effective than punishment for poor behavior. Expectations must be appropriate to the age and understanding of the child. The nurse encourages parents to try to be consistent, because mixed messages are confusing for the learner.

Timing the Time-Out

Most researchers agree that to be effective, discipline must be given at the time the incident occurs. It should also be adapted to the seriousness of the infraction. The child’s self-worth must always be considered and preserved (Carey et al., 2009). Warning the preschool child who appears to be getting into trouble may be helpful. However, too many warnings without follow-up lead to ineffectiveness. For the most part, spankings are not productive. The child associates the fury of the parents with the pain rather than with the wrong deed because anger is the predominant factor in the situation. The real value of the spanking is therefore lost. Beatings administered by parents as a release for their own pent-up emotions are totally inappropriate and can lead to child abuse charges. In addition, the parent serves as a role model of aggression. Whether a parent is affectionate, warm, or cold (uncaring) also plays a role in the effectiveness of child rearing.

Time-out periods, usually lasting 1 minute per year of age, with the child sitting in a straight chair facing a corner are considered an effective discipline technique. There should be no interaction or eye contact during the time-out period, and a timer with a buzzer should be used. Often a child will attempt interaction during this period by asking, “How much more time is left?” The child should learn that any interaction restarts the timer at zero. Using the child’s room or a soft comfortable chair for time-out is not effective, because the child will either fall asleep or engage in another activity and the objective of time-out is defeated. Time-out should be preceded by a short (no longer than 10-word) explanation of the reason and followed by a short (no more than 10 words) restatement of why it was necessary. Longer explanations are not effective for young children. If the child knows the rules and the behavior that will precipitate a time-out and receives no more than one warning that there will be a time-out if the undesirable behavior continues, he or she will learn self-control. Consistency is the key to helping the child learn acceptable behavior. Parents must be taught to resist using power and authority for their own sake. As the child matures and understands more clearly, privileges can be withheld as a consequence for undesirable behavior. The reasons for such actions are carefully explained.

Reward

Rewarding the child for good behavior is a positive and effective method of discipline. This can be done with hugs, smiles, tone of voice, and praise. Praise can always be tied with the act, such as “Thank you, Zoe, for picking up your toys,” or “I appreciate your standing quietly like that.” The encouragement of positive behavior eliminates many of the undesirable effects of punishment.

Rewards should not be confused with bribes. The parent may offer a child a reward if he or she behaves in a specific situation before an incident occurs. For example, the parent may say, “You may pick out one small toy after we are finished shopping if you behave during this trip.” If this agreement is not made before an incident and the child misbehaves and then is offered one small toy to behave, this is a bribe that serves to reinforce the bad behavior and is not a desirable technique of behavior management.

Consistency and Modeling

Being consistent is difficult for parents. Realistically, it is only an ideal to strive for—no parent is consistent all the time. Consistency must exist between parents as well as within each parent. It is suggested that parents establish a general style for what, when, how, and to what degree punishment is appropriate for misconduct. Parents who are lax or erratic in discipline and who alternate it with punishment have children who experience increased behavioral difficulties.

The influence of modeling, or good example, has been widely explored. Studies show that adult models significantly influence children’s education. Children identify and imitate adult behavior, verbal and nonverbal. Parents who are aggressive and repeatedly lose control demonstrate the power of action over words. Those who communicate, show respect and encouragement, and set appropriate limits are more positive role models. Finally, parents need assistance in reviewing parental discipline during their own childhood to recognize destructive patterns that they may be repeating. Modeling also involves teaching a child how to be self-sufficient and responsible. Asking children to do simple chores around the house is a good way to make them feel good about themselves; it gives them an opportunity to please you and learn at the same time, as long as the chore is not expected to be performed with expertise! Some chores a preschooler can perform include setting the table, sorting colored and white laundry, and picking up toys. If the chore is associated with a positive outcome, the concept of consequences can be learned. For example,” If we pick up the toys quickly, then we will have time to read a story before bedtime.”

Jealousy

Jealousy is a normal response to actual, supposed, or threatened loss of affection. Both children and adults may feel insecure in their relationship with the person they love. The closer children are to their parents, the greater is their fear of losing them. Children envy the newborn. They love the sibling but resent his or her presence. They cannot understand the turmoil within themselves (Figure 18-3). Jealousy of a new sibling is strongest in children under 5 years of age and is shown in various ways. Children may be aggressive and may bite or pinch, or they may be rather discreet and may hug and kiss the infant with a determined look on their face. Another common situation is children’s attempt to identify with the infant. They revert to wetting the bed or want to be powdered after they urinate. Some 4-year-olds even try the bottle, but it is usually a big disappointment to them.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree