Kathleen F. Jett

Bone and joint problems

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

It is so discouraging to wake up feeling so stiff and sore every morning. Just getting out of bed seems like a real effort, but I usually feel better after I have moved around a bit. I was always so athletic, I can’t understand how I have become so crippled up. And now I know that what my grandmother used to say about the weather affecting her rheumatism is really true. I can feel it when a storm is coming.

Mabel, age 80

I don’t know how folks with arthritis can stand being uncomfortable so much of the time. I know Mabel takes medications, but she still seems to be in a lot of pain and has so much trouble moving about. I’ll try to be as gentle as possible when I help her bathe.

Elva, student nurse

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Describe the most common bone and joint problems affecting older adults.

• Discuss the potential dangers of osteoporosis.

• Recognize postural changes that suggest the presence of osteoporosis.

• Explain some effective ways of preventing or slowing the progression of osteoporosis.

• Compare the differences in common arthritic conditions.

• Describe the nurse’s responsibility in care for the person with arthritic conditions.

Glossary

Bone mineral density (BMD) Mineral content of the bones.

Crepitus The sound or feel of bone rubbing on bone.

Osteopenia Loss of bone mineral density and structure at a mild to moderate level.

Osteophyte Excessive bone growth.

Osteoporosis Loss of bone mineral density and structure to a great degree.

Resorption The loss of a substance or bone by physiological or pathological processes.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Musculoskeletal system

A healthy musculoskeletal system not only allows the body to be upright but also is necessary for comfortably carrying out the most basic activities of daily living (ADLs). For some, later life is an opportunity to explore the limits of their ability and become master athletes. For others, later life is a time of significant restriction in movement. However, both athletes and nonathletes have to deal with the challenges of one or more of the musculoskeletal problems commonly encountered in later life.

The gerontological nurse attends to the needs of older adults with musculoskeletal problems and works to promote healthy bones and joints. In this chapter we discuss osteoporosis and the different forms of arthritis, and their implications for nursing intervention and the promotion of healthy aging.

Osteoporosis

In the normal process of growth, known as bone turnover, the bones build up mass (formation) and strength at the same time they are losing both through resorption. Peak bone mass is reached at about 30 years of age. After that, the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) is quite minimal at first but speeds up with age. For women, the period of the fastest overall loss of BMD is in the 5 to 7 years immediately following menopause.

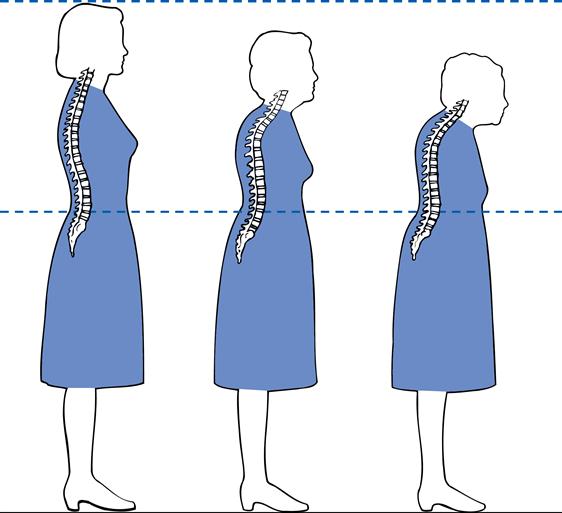

Osteoporosis means porous bone. Primary osteoporosis is sometimes thought to be part of the normal aging process, especially for women. Secondary osteoporosis is that which is caused by another disease state, such as Paget’s disease, or by medications, such as long-term steroid use. Both are characterized by low BMD and subsequent deterioration of the bone structure and changes in posture (Figure 18-1). Low BMD affects about 44 million or 55% of people over 50 years of age. Eighty percent of those affected are women, especially thin white women. Ten million have osteoporosis and the rest have osteopenia or a lesser degree of the loss of BMD (National Osteoporosis Foundation [NOF], 2011).

Osteoporosis is a silent disorder; a person may never know she has osteoporosis until a fracture occurs. It is diagnosed through a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan but is presumed in older adults with non-traumatic fractures, a loss of 3 inches or more in height, and/or kyphosis (see Figure 18-1). The nurse may be the one to identify the changes that had not yet been medically diagnosed. Without a diagnosis the person cannot be treated.

The most serious complication of osteoporosis is the increased risk for a fracture and subsequent death or disability. Each year more than 1.6 million older adults go to emergency rooms for fall-related injuries, the number one cause of fracture, trauma admissions to hospitals and injury-related deaths (NIH, 2011). Fractures of the hip, pelvis, spine, arm, hand, or ankle are those most commonly associated with osteoporosis. It was estimated that there were about 2 million related fractures in 2005 and the number is expected to climb (NOF, 2011). Among persons over 50 years of age, who were healthy and active before the fracture usually go home, but those with other health problems may not ever be able to return to independent living (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2011).

A number of factors increase or decrease a person’s risk for both osteopenia and osteoporosis. Some of these cannot be changed (e.g., gender, race, family history, or ethnicity), but others (e.g., calcium intake, exercise) are amenable to change (Box 18-1). African-American women have the highest BMD but are still at risk. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all women 65 years of age or older and younger women with significant risk factors (e.g., family history) be screened for osteoporosis. There is currently insufficient evidence to make a recommendation about screening in men (USPSTF, 2011). If the screening is positive the nurse can advocate for the elder to receive appropriate treatment. The nurse can always recommend preventive measures such as adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D and smoking cessation (see later).

Implications for gerontological nursing and healthy aging

With the treatments and interventions now available, some osteoporosis can be prevented or treated and stabilized to some extent. It is always possible to promote healthy aging for the person with osteoporosis. However, for those already with osteoporosis it becomes paramount to reduce osteoporosis-related injury.

Reducing osteoporosis-related risk and injury

Measures to prevent osteoporosis-related injury or progression of the disease include exercise, nutrition, and lifestyle changes to reduce known risk factors. As with many other diseases, smoking is one risk factor that can be changed. Home safety inspection and education regarding injury prevention strategies are essential (see Chapter 13). An assortment of print and interactive educational materials for both the lay and professional audience can be found at http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Bone/Osteoporosis/default.asp.

Weight-bearing physical activity and exercises help to maintain bone mass (see the Evidence-Based Practice box). Brisk walking and working with light weights apply mechanical force to the spine and long bones (see Chapters 11 and 13). Muscle-building exercises help to maintain skeletal architecture by improving muscle strength and flexibility. The Asian art of T’ai Chi has been used successfully for strengthening of both ambulatory and nonambulatory elders (Wayne et al., 2007, 2010). T’ai Chi and exercise have the added advantage of improving balance and stamina, which may prevent falls or limit the damage if a fall should occur.

Patient teaching includes key aspects of the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Information about the sites most vulnerable to injury should be provided. Explanation should be given about changes in the upper spine that occur when vertebrae are weakened, and about the pain that results from strain on the lower spine that is caused by the effort to compensate for balance and height changes attributable to alteration of the upper spine. Education also includes the appropriate way to take medications and how to handle their side effects.

Fall prevention is especially important to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with osteoporosis. Shoes with good support should be worn. Handrails should be used, and walking in poorly lighted areas should be avoided. Basic body mechanics, such as how to lift heavy objects, should be learned. Use of step stools or chairs for reaching things in high places should be discouraged; instead these things can be moved to a more reachable level. Attention must be paid to home safety and improvements should include good lighting, railings, and other aids as needed. Walkways should be kept free of obstacles; loose rugs and electrical cords should be arranged so that they do not cause falls. Environmental safety and fall prevention is addressed in detail in Chapter 13.

Pharmacological interventions

Considerable progress has been made in the last decade in the development of pharmacological treatments for both the prevention and the treatment of osteoporosis. Adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D is recommended for persons at all ages and must be taken with all of the prescribed treatments currently available (Ragucci & Shrader, 2011).

Ideally, optimal nutrition in late life has followed a lifetime of good eating habits (see Chapter 9). The diet during adolescence is probably a key to healthy bones later. A balanced diet that includes food sources of calcium is best (Box 18-2). Women over 50 years of age and men over 70 years of age should ingest 1200 mg of calcium per day; 1000 mg a day is recommended for men between 51 and 69 years of age and can come from combined dietary and supplementary sources (Kessenich, 2007; NIH, 2011). If using supplements, combination calcium–vitamin D supplements (e.g., Caltrate-D) are recommended. The doses are best spread over the course of the day; for example, 400 mg of calcium three times a day. The present recommendation includes the regular use of 600 to 800 international units of supplemental vitamin D to achieve blood levels of greater than or equal to 50 nmol/L and less than 125 nmol/L (Office of Dietary Supplements [ODS]/NIH, 2011). Older adults are at particularly high risk for vitamin D deficiencies due to changes in the skin that reduce the ability to synthesize vitamin D efficiently. For those living in institutional settings or northern climates, the reduced opportunities for sunlight exposure only increase the risk for deficiencies.