The Toddler

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

3. Discuss speech development in the toddler.

5. List two developmental tasks of the toddler period.

6. Discuss the principles of guidance and discipline for a toddler.

7. Discuss how adults can assist small children in combating their fears.

9. Describe the nutritional needs and self-feeding abilities of a toddler.

11. Describe the characteristic play and appropriate toys for a toddler.

Key Terms

autonomy (p. 406)

cooperative play (p. 418)

egocentric thinking (p. 418)

negativism (p. 406)

object permanence (p. 408)

parallel play (p. 418)

ritualism (p. 406)

temper tantrums (p. 410)

time-out (p. 410)

toddlers (p. 406)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

General Characteristics

Children between 1 and 3 years of age are referred to as toddlers. They are able to get about by using their own powers and are no longer completely dependent persons. By 1 year of age, they have generally tripled their birth weight and gained control of their head, hands, and feet. The remarkably rapid growth and development that took place during infancy begins to slow down. The toddler period presents different challenges for the parents and the child.

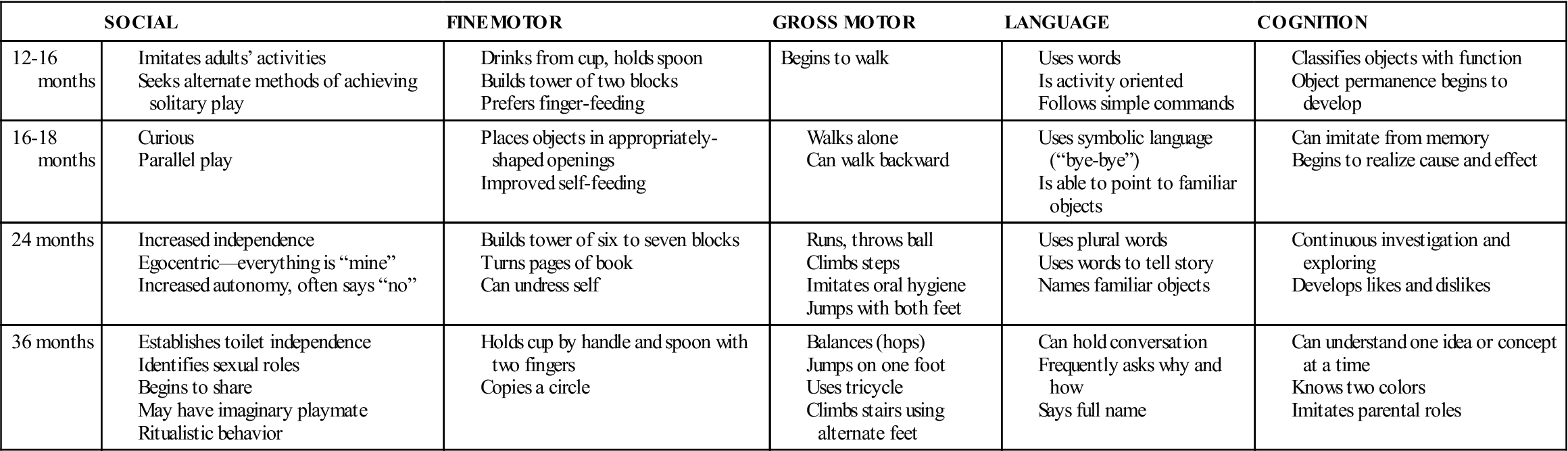

The toddler is in Erikson’s stage of autonomy versus shame and doubt, which is based on a continuum of trust established during infancy (see Chapter 15). Along with the toddler’s increasing independence and curiosity to explore the widening environment come many challenging tasks to be mastered, including toilet training, self-feeding, self-dressing, and speech development. One major parental responsibility is to maintain safety while allowing the toddler the opportunity for social and physical independence. Another major parental responsibility is to maintain a positive self-image and body image in the child whose behavior is inconsistent and often frustrating. Toddlers alternate between dependence and independence. They test their power by saying “no” frequently. This is called negativism. Offering limited choices and making use of distraction can be helpful strategies in handling toddlers (too many choices can cause confusion). Developing self-control and socially acceptable outlets for aggression and anger are important factors in the formation of personality and behavior. Ritualism is another characteristic of toddler behavior. Toddlers increase their sense of security by making compulsive routines of simple tasks, and therefore their rituals should be respected. Table 17-1 summarizes the toddler’s physical development, social behavior, and abilities at various ages.

Table 17-1

Physical Development, Social Behavior, and Abilities of Toddlers

| SOCIAL | FINE MOTOR | GROSS MOTOR | LANGUAGE | COGNITION | |

| 12-16 months | Begins to walk | ||||

| 16-18 months | |||||

| 24 months | |||||

| 36 months |

Physical Development

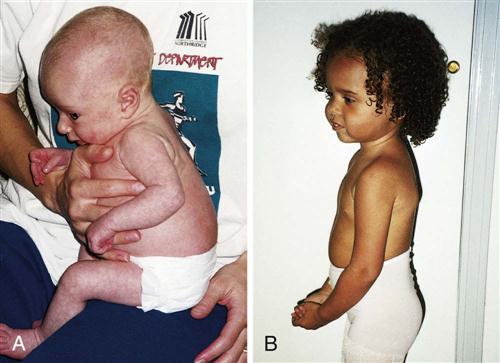

The toddler’s body changes proportions (Figure 17-1). The legs and arms lengthen through ossification and growth in the epiphyseal areas of the long bones. The trunk and head grow more slowly. The toddler gains 1.8 to 2.7 kg (4 to 6 lb) per year. The birth weight has quadrupled by 2.5 years of age. The toddler grows 10 cm (4 inches) per year in height. The height of a 2-year-old is thought to be one half of the potential adult height of that child. The height and weight are plotted carefully on a growth chart during each clinic visit to reflect what should be a steady pace of growth and development (see Figure 15-3).

The rate of brain growth decelerates. The increase in head circumference during infancy is 10 cm (4 inches), whereas during the second year of life it is only 2.5 cm (1 inch). Chest circumference continues to increase. After the second year the child appears leaner because the chest circumference begins to exceed the abdominal circumference. The protuberant abdomen flattens when the muscle fibers increase in size and strength.

Myelination of the spinal cord is practically complete by age 2 years, allowing for control of anal and urethral sphincters. Bowel and bladder control is usually complete by 2.5 to 3 years of age.

Respirations are still mainly abdominal but shift to thoracic as the child approaches school age. The toddler is more capable of maintaining a stable body temperature than is the infant. The shivering process, in which the capillaries constrict or dilate in response to body temperature, has matured.

The skin becomes tough as the epidermis and dermis bond more tightly, which protects the child from fluid loss, infection, and irritation. The defense mechanisms of the skin and blood, particularly phagocytosis, work more effectively than they did during infancy. The lymphatic tissues of the adenoids and tonsils enlarge during this period. The eustachian tubes continue to be shorter and straighter than in the adult. Tonsillitis, otitis media, and upper respiratory infections are common problems. Eruption of deciduous teeth continues until completion at about 2.5 years of age (see Figure 15-13).

The blood pressure of a toddler may average 90/56 mm Hg; the respiratory rate slows to 25 breaths/min, and breathing continues to be abdominal. The pulse of a toddler slows to a range of 70 to 110 beats/min. Digestive processes and the volume capacity of the stomach increase to accommodate a three-meal-a-day schedule.

Sensorimotor and Cognitive Development

The senses and motor abilities of the toddler do not function independently of one another. Two-year-old toddlers reach, grasp, inspect, smell, taste, and study objects with their eyes. Their attention becomes centered on characteristics of their surroundings that capture their interest. Binocular vision is well established by age 15 months. Visual acuity is about 20/40 by 2 years of age.

As memory strengthens, toddlers can compare present events with stored knowledge. They assimilate information through trial and error plus repetition. They try alternative methods of accomplishing a goal. Thought processes advance, preparing the way for more complex mental operations. The sensorimotor and preconceptual phase of development described by Piaget develops rapidly between 1 and 3 years of age, and the toddler’s behavior reflects this.

Separation anxiety, which consists of protest, despair, and detachment, develops in infancy and continues throughout toddlerhood. Toddlers are able to tolerate longer periods of separation from parents to explore their environment. They become aware of cause and effect. Often they correlate a type of object with its function. For example, if their toys are stored in a paper bag, they will gleefully open any paper bag they see, expecting to find toys. If the bag contains garbage or drugs, they can be injured or may be punished. This can be confusing to the toddler and frustrating to the parents.

The concept of spatial relationships develops, and toddlers are able to fit square pegs in a square hole and round pegs in a round hole. Toys should be selected to promote this ability. Object permanence continues to develop, and the toddler becomes aware that there may be fun items behind closed doors and in closed drawers. The toddler’s curiosity and ability to explore make it important to educate parents to keep dangerous objects out of their reach. The toddler begins to internalize standards of behavior as evidenced by saying “no-no” when tempted to touch a forbidden object.

The toddler copies the words and the roles of the models seen in the home. The toddler may “help Mommy clean” or “help Daddy shave.” By 2 years of age there is recognition of sexual differences.

Toddlers may confuse essential with nonessential body parts. Expelling feces and flushing them down the toilet can be upsetting to some toddlers because they may feel they expelled a part of themselves that has disappeared. Toddlers’ body image and self-esteem may be impaired if they are scolded in a way that makes them feel they are bad rather than their behavior. The nurse must help the parents develop skills that will enable toddlers to feel they are loved even though the specific behavior is unacceptable.

Speech Development

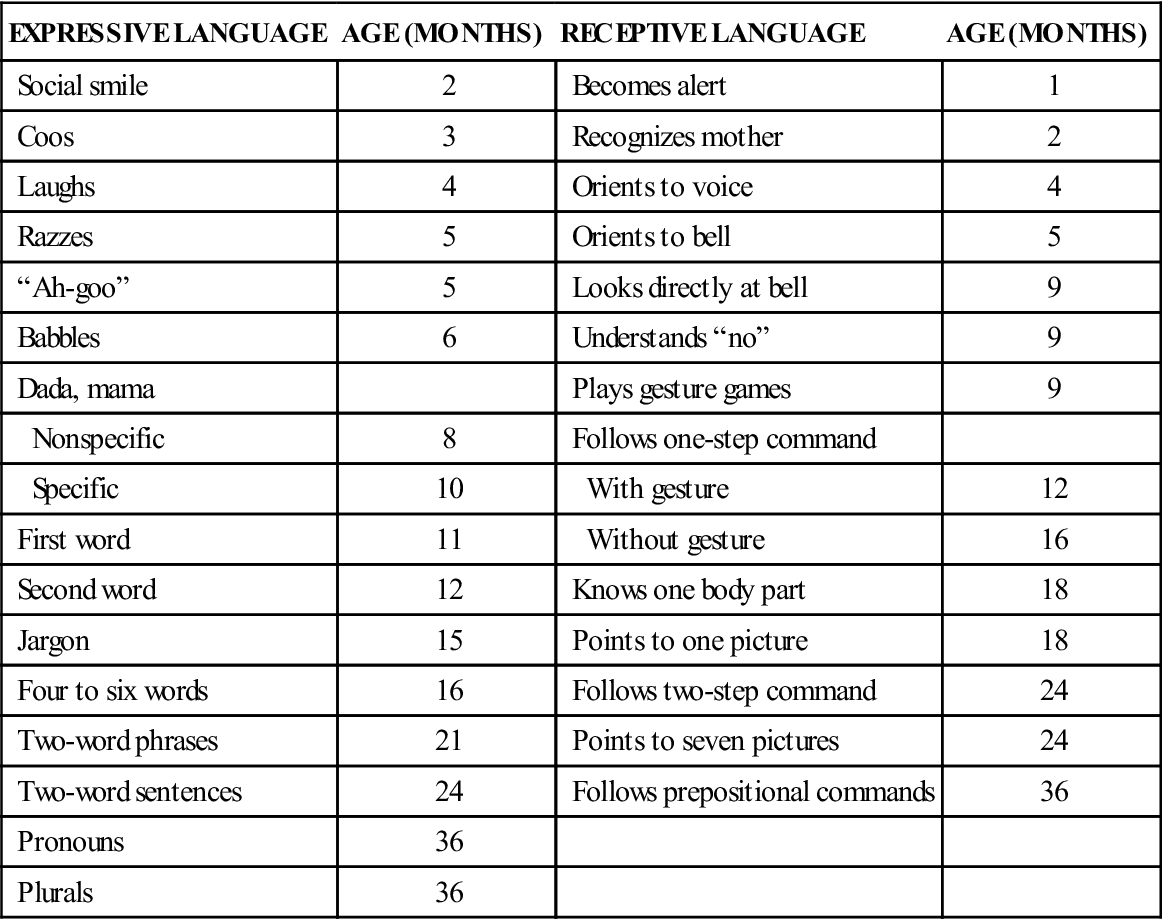

Language development parallels cognitive growth. The increase in the level of comprehension is particularly striking and exceeds verbalization. By 3 years of age the child has a rather extensive vocabulary of about 900 words. Speech is more than 90% intelligible (Table 17-2). At about the end of the first year, the infant begins to make noises that sound like “bye-bye,” “ma-ma,” and “da-da.” When toddlers see the happy response to these sounds, they repeat them. This is true throughout the toddler period. To want to learn to talk, small children must have an appreciative audience.

Table 17-2

| EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE | AGE (MONTHS) | RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE | AGE (MONTHS) |

| Social smile | 2 | Becomes alert | 1 |

| Coos | 3 | Recognizes mother | 2 |

| Laughs | 4 | Orients to voice | 4 |

| Razzes | 5 | Orients to bell | 5 |

| “Ah-goo” | 5 | Looks directly at bell | 9 |

| Babbles | 6 | Understands “no” | 9 |

| Dada, mama | Plays gesture games | 9 | |

| Nonspecific | 8 | Follows one-step command | |

| Specific | 10 | With gesture | 12 |

| First word | 11 | Without gesture | 16 |

| Second word | 12 | Knows one body part | 18 |

| Jargon | 15 | Points to one picture | 18 |

| Four to six words | 16 | Follows two-step command | 24 |

| Two-word phrases | 21 | Points to seven pictures | 24 |

| Two-word sentences | 24 | Follows prepositional commands | 36 |

| Pronouns | 36 | ||

| Plurals | 36 |

Modified from Montgomery, T. (1994). When not talking is the chief complaint. Contemporary Pediatrics, 11(9), 49.

Children first refer to animals by the sounds the animals make. For example, before saying “dog,” the toddler repeats “bow-bow.” Soon the child can say short phrases such as “Daddy gone car.” Toddlers also respond to tone of voice and facial expression. If an adult sounds threatening, the toddler may answer “no” and then repeat it in a louder voice.

Sometimes adults scold the child merely for being too young to understand what is requested. However, imagine being punished in a foreign country because you could not speak or comprehend the language well enough to defend yourself. Adults who show empathy to the small child can help to minimize their frustrations.

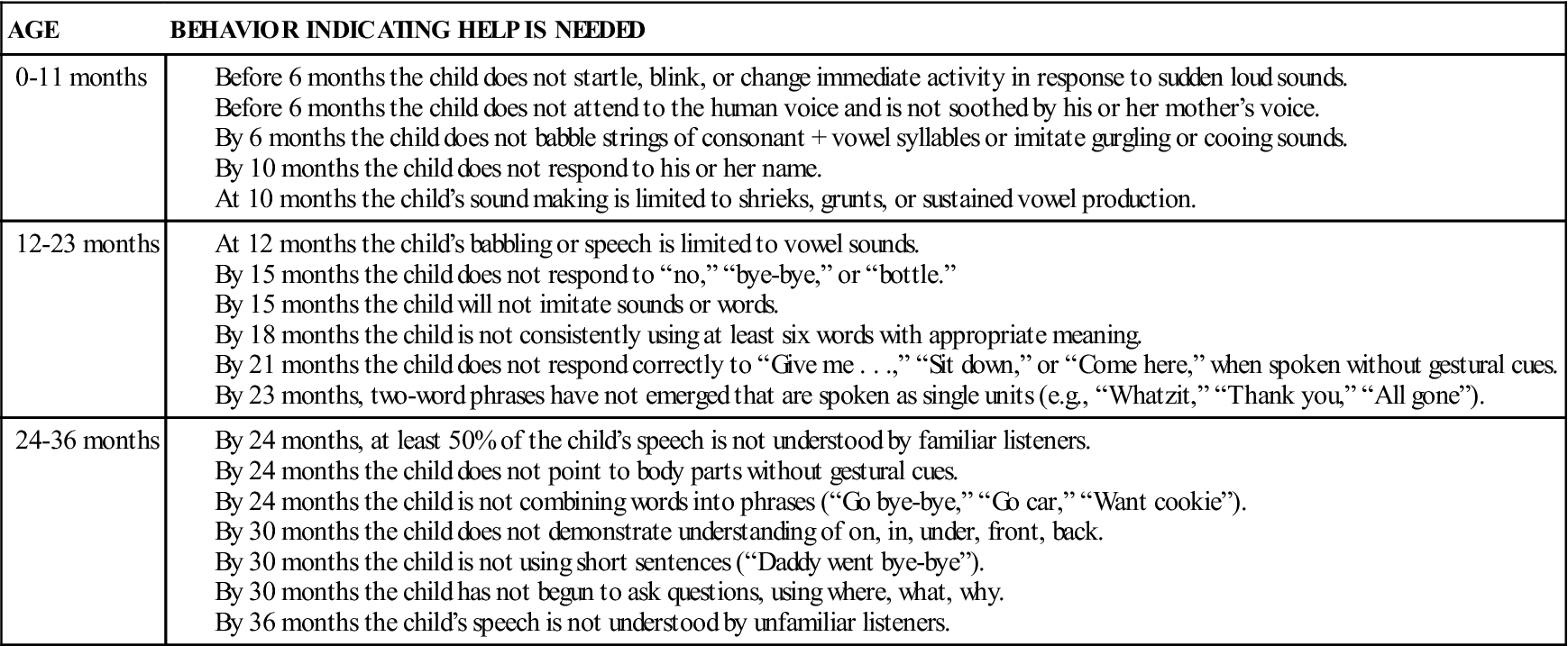

Parents who are concerned about their child’s delayed speech can discuss it with their health care provider during a routine physical examination so it can be evaluated in light of total physical growth and development (Table 17-3). Many late talkers are perfectly normal children who prefer listening over active participation. Lead poisoning and hearing deficits should be ruled out before screening for other developmental problems such as autism (Box 17-1). Many common household items, such as vertical window blinds and decorative metal vases, contain lead. Autism is discussed in Chapter 33.

Table 17-3

When a Child with a Communication Disorder Needs Help

From Kliegman, R., Marcdante, K., Jenson, H., & Behrman, R. (2005). Nelson’s essentials of pediatrics (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders.

Guidance and Discipline

Discipline for the toddler involves guidance. The goal is to teach, not to punish. Teaching the toddler self-control with positive self-esteem is more desirable than encouraging a completely submissive, “obedient” child. The toddler who scribbles on the wall must be given the opportunity to scribble on paper, a more socially acceptable outlet.

Temper tantrums (uncontrolled anger reactions) often occur during the toddler years, and parent responses reinforce to the child either the desirability or the risks involved with such behavior. Expectations must be commensurate with the child’s physical and cognitive abilities. Toddlers get into many situations that are over their heads. When adults make firm decisions, the problem is resolved, at least for the time being. The child feels secure.

Limit setting should include praise for desired behavior as well as disapproval for undesired behavior. A time-out period in a safe place helps the child to develop the ability to tolerate delayed gratification and self-regulation. Timing should not begin until the child has settled down. The child is praised once calm. Timing for time-out is usually based on 1 minute per year of age.

Children, like adults, seek approval. It is effective and helps to increase their self-confidence. The positive approach should be taken as often as possible. One assumes that the toddler is going to be good rather than bad. “Thank you, Johnny, for giving me the matches” will make them arrive in your hand more quickly than “Give me those matches right now,” said in a threatening tone. The use of fear or physical aggression should not be a part of discipline, because it does not foster self-control and can lead to physical or mental abuse of the child.

Fear is a valuable emotion to the child if it does not become too intense. Unfortunately, many children fear situations that are not in themselves dangerous, and this sometimes deprives them of activities that otherwise would be enjoyable. If the parent warns, “Be careful, don’t fall,” when a toddler begins to ride a tricycle, the toddler may develop a fear of the risk taking that may be involved in experiencing new activities.

The physical and mental health of the child at the time of a fear-provoking experience affects the extent of the reaction. If the child is alone, fear may be greater than if someone such as a parent or nurse is present. Once a fear has been learned, it is more difficult to eliminate. Clinging to favorite possessions and repetitive rituals are self-consoling behaviors for the toddler, particularly at bedtime and during separation from parents.

Stress increases fear of separation. Adults should attempt to control their own fears in the presence of young children. Respect and understanding should always be accorded to children who are afraid. Making fun of the fear or shaming the child in front of others is detrimental to self-esteem.

Many toddlers who independently explore the clinic examining room while waiting to be examined may cling to the parent when the stranger (the health care provider) enters the room and approaches the child. The toddler who does not seek the parent during stressful situations or turns to a stranger for comfort reflects a need for closer evaluation of the parent-child relationship.

The “terrible twos,” during which negativistic behavior is predominant, begin the disciplinary pattern of the family that will carry throughout childhood and affect the child’s personality. Corporal punishment, involving spanking, is accepted in many traditional cultures as the mainstay of discipline. However, regular spanking reflects a desperate effort by the parent to gain control over a toddler who is exercising his or her beginning autonomy (independent functioning) and developing negativism. Potential injury, child abuse, and reciprocal aggressive behavior in the child can be avoided with careful parental guidance concerning alternative techniques of discipline. Time-out, limit setting, clear communication, and frequent rewards and approval for positive behavior are effective noncorporal techniques of discipline.

Communicating love and respect to the child with a clear message that it is the behavior, not the child, that is disapproved of by the adult are the keys to effective discipline. Behavior problems that can occur during early childhood are detailed in Table 17-4.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree