Gathering Information in Naturalistic Inquiry

Key terms

Audit trail

Field notes

Focus group

Gaining access

Investigator involvement

Life history

Member checking

Participant observation

Peer debriefing

Reflexivity

Rich point

Saturation

Triangulation

Gathering information in naturalistic forms of inquiry involves a set of investigative actions that are quite divergent in purpose, approach, and process from experimental-type research. In naturalistic inquiry, knowledge emerges from and is embedded in the unique and shared understandings of human phenomena of interest.

The overall purpose of gathering information in naturalistic inquiry is to uncover multiple and diverse perspectives or underlying patterns that illuminate, describe, relate, and even predict the phenomena under study within the context in which phenomena occur. By “context,” we mean the physical, virtual, intellectual, social, economic, cultural, spiritual, and other types of environments in which human experience unfolds. Thus, different from experimental-type approaches, which also aim to predict, the processes of collecting information in naturalistic inquiry serve as discovery and revelation in a contextual field, not verification or falsification of a theory through the specification, collection, and analysis of data in a carefully controlled environment. The investigator gathers sufficient information that leads to description, discovery, understanding, interpretation, meaning, and explanation of the rich mosaic of human experiences.

As you now know, many distinct perspectives compose the rubric of naturalistic inquiry. Thus, there is wide variation in the information-gathering approaches of researchers conducting naturalistic inquiry. For example, in semiotics the focus of data collection is on discourse, symbol, and context.1 In classic ethnography, the focus of data collection may be broader than in semiotics and may include verbal exchanges, behavioral patterns, and physical objects.2

Four information-gathering principles

Although the process of gathering information differs across the types of naturalistic inquiry, four basic principles provide guidance for action: (1) the nature of involvement of the investigator; (2) the inductive, abductive process of gathering information, analyzing the information, and gathering more information; (3) the time commitment in the actual or virtual field; and (4) the use of multiple data collection strategies.

Investigator Involvement

In experimental-type research, investigators implement a set of procedures designed to remove themselves from informal or nonstandardized interactions with study participants. Naturalistic inquiry, however, is based on investigator involvement and active participation (to a greater or lesser degree) with people and other sources of information, such as artifacts, written historical documents or virtual text and image, and pictorial representations. When working directly with humans, the quality of the data collected often depends on the investigator’s ability to develop trust, rapport, and mutual respect with those participating in or being studied. The level and nature of the investigator’s involvement with people and other sources of information, however, depend on the specific type of naturalistic study that is pursued (Table 17-1).

TABLE 17-1

Investigator Involvement in Gathering Information from Study Participants in Naturalistic Designs

| Type of Naturalistic Inquiry | Investigator Involvement |

| Endogenous team decisions | Variable; flexible; depends on study |

| Participatory action team decisions | Variable; flexible; depends on study |

| Phenomenological | Active listener |

| Heuristic | Fully participatory |

| Life history | Active listener |

| Ethnographic | Fully participatory |

| Grounded theory | Fully participatory |

In most forms of naturalistic inquiry, but particularly in classic ethnography, life history, grounded theory, and heuristic designs—the process of eliciting stories, personal experiences, and the telling of events—is based on a strong relationship or bond that forms between the investigator and the informant. Some researchers characterize this bond as a “collaborative endeavor” or “partnership.” In these approaches to inquiry, the primary instrument for gathering trustworthy information from study participants is the investigator. As Tedlock stated (in Denzin and Lincoln):

By entering into firsthand interaction with people in their everyday lives, ethnographers can reach a better understanding of the beliefs, motivations, and behaviors of their subjects than they can by using any other method.3

The investigator as a data-gathering instrument is a logical extension of the primary contention of naturalistic inquiry. This position, shared by many forms of naturalistic inquiry, maintains that the only way to “know” about the “lived” experiences of individuals is to become intimately involved and familiar with the life situations or representations of those who experience them. The extreme of this position is found in heuristic inquiry, in which the investigator investigates his or her personal lived experience. In phenomenological research, the investigator develops rapport with study participants but engages in active listening to understand the experiences of others. In ethnography, the researcher, as the primary data-gathering instrument, strives for intimate familiarity with the people and context in the study. By engaging in an active learning process through looking, watching, listening, participating, interviewing, and reviewing materials, the investigator enters the “life world” of others and uncovers what it means to live those experiences.

In endogenous and participatory action research, the level of investigator involvement in data collection varies depending on the way in which the study team chooses to proceed. In these forms of naturalistic inquiry, the investigator tends to serve more as a facilitator of the research process and may or may not be directly involved in the various data collection strategies implemented by the team of participants.

Naturalistic forms of inquiry may employ others in the data-gathering process in addition to the primary investigators. This strategy is particularly useful in studies involving multiple field sites or when the volume of interviews is high and requires assistance from others, who may be researchers, the subjects of the inquiry, or individuals trained in the rigorous procedures that characterize the study. In these cases, the investigator and data gatherers form a team and work together to develop consensus on methods and style to ensure similarity and consistency in the use of techniques for building rapport, as well as for probing and eliciting responses. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the data, the team must also work together to share field impressions, notes, and emerging analytical categories and themes.

For example, let’s say you want to conduct a study to examine the attitudes of rural residents toward law enforcement’s role in substance abuse prevention in a particular geographic region of the United States. Because the geographic area of interest is vast, more than one investigator is necessary to collaborate on the project and gather data. You form a team of investigators composed of parents, health and social service professionals, and students and you all meet every 2 weeks to discuss and agree upon where to obtain interview data, how to conduct the interviews, and how to record and aggregate responses. Although each member of the investigative team has a particular style and preferred methodologies, all agree to how best to identify and approach informants, type and level of probing questions and initial analytic approach.

Information Collection and Analysis

In naturalistic inquiry, the act of gathering information is intimately entwined with analysis—that is, collecting data and conducting analysis reciprocally inform one another. Thus, once established in the field, the investigator evaluates the information obtained through observation, examination of artifacts and images, recorded interviews, and participation in relevant activities. These initial analytical efforts detail the “who, what, when, and where” aspects of the context, which in turn are used to further define and refine subsequent data collection efforts and directions.

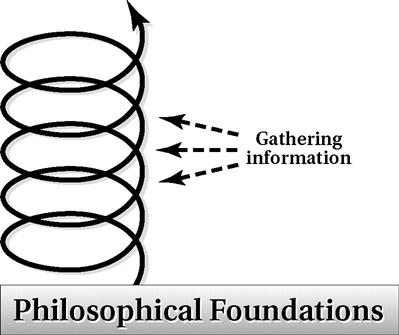

The dynamic process of ongoing data gathering, analysis, and more data gathering can be graphically represented by the “spiral” design used in this text. In the spiral, as analysis and data collection are refined, the investigator moves from a broad conception of the field to a more in-depth, richer, and “thick” understanding and, when indicated in the design, an interpretation of multiple field “realities.”4

Time Commitment in the Field

The amount of time spent immersed in a physical or virtual field setting varies greatly across the types of naturalistic inquiry. In some studies, understanding a natural or virtual setting can be time-consuming because of the complexity of the initial query and the context that is being studied. In any type of naturalistic inquiry, however, the investigator must become totally immersed in the setting or involved with the phenomenon of study. “Immersion” means that the investigator must spend sufficient time in the field to ensure that a complete description is produced. In ethnographic research, spending time “hanging out”—interviewing, observing, and participating—has traditionally been called “prolonged engagement” in the field. In ethnography, prolonged engagement is essential to ensure that the investigator reaches an in-depth understanding of the particular cultural group of focus.5 In other types of naturalistic design, engagement may be structured in diverse sequences, such as immersion on specific days and times or for specific events.

So how much time is necessary? The amount of time spent in the field may vary from specified hours each day or week to a few months to years, depending on the nature of the initial query and its scope, the availability of resources that support the investigator in the endeavor, the amount of time available to the investigator, and the specific design strategy that is followed.

Whether spending a short period or a long time in the field, the investigator must determine the point at which sufficient information has been obtained. At that point, the investigator leaves the field and engages in a final analytic or interpretive process that involves preparing one or more final reports. This point is sometimes referred to as “saturation.” Indications of saturation include the investigator no longer being puzzled or surprised by observations, events, or by what people say in the field; the investigator predicting behaviors or outcomes; and information becoming redundant compared with information already collected and learned by the investigator. When the investigator begins to hear the same story, can predict what a respondent is going to say, or can anticipate image, text, and meaning, it is time to leave the field (see later discussion on saturation).

Multiple Information-Gathering Strategies

Some methodologists suggest that by its nature, all naturalistic inquiry is multimethod.6 Because we define “multimethod” as the use of strategies from more than one research tradition, we do not see naturalistic inquiry as multimethod in itself. However, part of the naturalistic tradition is often characterized by the typical use of numerous data collection methods in a single study. Because different strategies are designed to derive information from numerous sources, the use of multiple approaches to obtain information enhances the investigator’s capacity to obtain a complex and rich understanding of the phenomenon under study. It is therefore common practice to use more than one data collection strategy even if a query is small in scope. Throughout and at the end of the data collection process, all sources of information are analyzed to ensure that they support a rich descriptive or interpretive scheme and set of conclusions.

Investigators can use many data-gathering strategies, many of which are discussed later in the book In most types of naturalistic inquiry, investigators may not know before entering the field exactly which strategies they will use. Although thought and planning occur in all phases of naturalistic inquiry, the final decision to use a particular approach to collecting information occurs as the research progresses. As noted, an important part of the naturalistic process of data collection occurs during fieldwork, throughout which the investigator must decide which data collection techniques to use and at which point each should be introduced.

No standard approach is available to indicate which strategy should be used and when it should be introduced across the different forms of naturalistic inquiry. Data collection decisions are specific to the research query, the preferred way of knowing by the investigator, and the contextual opportunities that emerge while in the field. In a phenomenological study, for example, some investigators prefer to interview respondents first and then review written documents, virtual sources, journals, medical records, and other materials. In this type of study, it is considered critical initially to listen in an interview to the emotions and feelings naturally expressed by individuals asked to reflect on their experiences. Reading the literature or other textual sources before the interviewing process may introduce deductive thinking or preconceived analytical frames that may preclude attentive listening to the experiences of individuals. In contrast, some ethnographers prefer to initially “hang out” in the field and use the data collection strategy of observation before introducing interviewing or other collection strategies. Still other investigators initially conduct open-ended interviews with key informants and then engage in observation. Other strategies, such as recordings, standardized questionnaires, or review of documents or images, may be introduced at subsequent stages of fieldwork.5

Consider this example. Suppose you are interested in learning about the benefit of virtual world interaction to individuals who interact on virtual disability sites. There are numerous ways that you could enter the field. You might join and virtually hang out as an avatar, or you might immediately start a conversation with another avatar in the virtual field. Both methods would serve the purpose of gaining entry, but each would elicit a different scope of information and guide you in a different direction for further information gathering.

Overview of Principles

The hallmark of gathering information for the naturalistic researcher is that this action process is purposive and occurs in and is responsive to the context in which the investigation is taking place. Data-gathering actions are designed to examine the context and all that occurs within it. No standardized data collection procedures structure studies or set criteria for rigor. Rather, the critical components of information-gathering actions tend to be diverse, based on the particular form of inquiry and the investigator’s ongoing judgments about what approaches can elicit the most relevant and illuminating data. Usually, the investigator is actively involved in the context over a prolonged time to ensure sufficient immersion in the phenomena under study. However, the level of investigator involvement varies depending on the form of inquiry. In all forms of naturalistic inquiry, best practice involves the use of multiple strategies to obtain information in an ongoing and integrated data collection and analytical process.

These basic components or guiding principles in data gathering yield descriptions, interpretations, and understandings of phenomena that are embedded in specific contexts and complex interrelationships. The complexity of phenomena is preserved in all representations and reports by the nature of the data-gathering process. Let us examine how these principles are implemented and how naturalistic inquiry actually works.

Information-gathering process

What is the process of conducting fieldwork or gathering information? Although the process has been variably defined, we have borrowed the classic and enduring structure suggested by Shaffir and Stebbins7 in the early 1990s because of its simplicity and comprehensiveness and continued relevance to the range of designs within the naturalistic tradition. Shaffir and Stebbins view the action process of data collection in naturalistic inquiry as four interrelated parts or considerations: context selection and “getting in the field,” “learning the ropes” or obtaining meanings of the setting, “maintaining relations,” and “leaving the field.”7 Although these actions appear to represent distinct phases or research steps, the process is truly integrated; each component overlaps and shapes the other.

Selecting the Context

The first decision about data collection in naturalistic research is where or in what context information should be obtained. The researcher must “bound” the study by depicting a context that is conceptual, virtual, or locational (see Chapters 12 and 14). Because naturalistic research focuses on the natural research context, as well as what happens in it, selection of a context is an important factor in gathering data. The context may be the private lives of famous people, the interrelationships of a surgical team, the world of hospice specialists, the meaning of disability to avatars in a virtual disability world, or the meanings of caregiving to immigrant families.

Context selection may sound simple, but there are several important considerations. First, the specification of a context must be practical or realistic to study. For example, how realistic is it to propose an inquiry to study the private lives of famous people? Will you be able to gain access to such individuals? Will these people choose to participate in this type of study, given that agreement will jeopardize their privacy?

Second, in bounding a study to a particular context, the researcher must be careful not to limit the focus and thus the opportunity to obtain a full picture of the phenomenon under investigation. Consider the following examples.

It is important to recognize that identifying the context of a naturalistic study will depend, in part, on the nature of the query, the design strategy, and the characteristics of the persons being studied.

Gaining Access

After the context for the research endeavor is identified, the investigator must gain access to it. This is not as simple as it may sound. Gaining access to the context of the study may require strategizing, negotiating with key individuals who may serve as gatekeepers, registering for a virtual world and even creating an avatar, and perhaps renegotiating after initial entry has occurred. In some cases, the investigator may already be a part of the natural context.

Suppose you are a student and want to understand the process of becoming a health professional following graduation. As a student in health care, you are actually an “insider” of part of particular context. Although access is not a problem in student professional socialization, access to other aspects to fieldwork may be challenging. However, even as an “insider student,” you will have to work hard to understand how your new knowledge and previous experiences influence the information you gather and interpret.

If the investigator is an “outsider,” access must be obtained. Mechanisms for gaining access have been extensively discussed in the literature, particularly by ethnographers.5,8 How the researcher gains access into a context can influence the entire course of the research process. Gaining access involves obtaining permission to enter and become part of the social or cultural setting. Investigators may use different strategies, depending on the nature of the context and their initial relationship to it. Formal introduction to an informant by another, slowly building rapport through participation, joining a club or virtual context, and gift giving are techniques used by investigators to enter a field.

Gaining access may be simple but can also take time and hard work. You need to clarify the ways you intend to be involved in the context and the implications of your study for the participants.

An important consideration in obtaining access is the degree to and the way in which the intent of your study is presented to participants (Box 17-1). The researcher must decide on the extent to which the research activity is revealed to those being observed or interviewed. Although disclosure of the purpose and scope of the research is most often made clear to those informants who provide initial access, the specifics of the research activity may remain vague to others who are either observed or interviewed at different times in the course of fieldwork. The extent of overt or covert research activities varies in any type of inquiry depending on the context, varies from study to study, and has important ethical concerns for researchers.

Assume that you want to examine the initial meanings attributed to the diagnosis of breast cancer among women in their 20s. This approach represents a rather focused query that could require a few months of interviewing women in this age group who have recently learned of their diagnosis. Or you might even spend several hours in a group interview with this same group of informants, significantly reducing the time in the filed. Even if you plan to observe providers interacting with these women, your observations will be confined to this early treatment phase.

Assume that you want to examine the initial meanings attributed to the diagnosis of breast cancer among women in their 20s. This approach represents a rather focused query that could require a few months of interviewing women in this age group who have recently learned of their diagnosis. Or you might even spend several hours in a group interview with this same group of informants, significantly reducing the time in the filed. Even if you plan to observe providers interacting with these women, your observations will be confined to this early treatment phase. Assume you want to study how children with diagnoses of learning disabilities learn to cope with and adapt to their differences. Identifying the classroom as the main context of the investigation may be too narrow. It may enable you to identify and describe the strategies that children use in that context, but it may not enable you to understand the full range of adaptive mechanisms that are used in learning in other contexts and how these mechanisms are obtained.

Assume you want to study how children with diagnoses of learning disabilities learn to cope with and adapt to their differences. Identifying the classroom as the main context of the investigation may be too narrow. It may enable you to identify and describe the strategies that children use in that context, but it may not enable you to understand the full range of adaptive mechanisms that are used in learning in other contexts and how these mechanisms are obtained. You are interested in studying the interrelationships and behaviors of a surgical team. You initially plan to examine the interactions of the surgical team during surgery. However, observations of this context may be too limiting. It may not yield a complete understanding of the interprofessional relationships that inform interactions in the specific context of surgery. Examining professional behaviors in other contexts, such as in the cafeteria, at staff meetings, or in social engagements, may provide important insights.

You are interested in studying the interrelationships and behaviors of a surgical team. You initially plan to examine the interactions of the surgical team during surgery. However, observations of this context may be too limiting. It may not yield a complete understanding of the interprofessional relationships that inform interactions in the specific context of surgery. Examining professional behaviors in other contexts, such as in the cafeteria, at staff meetings, or in social engagements, may provide important insights. You are interested in examining the functional capacities of persons with traumatic brain injuries. If the context for the study is functional capacity in a clinical setting, the informant may be maximally functional in this particular setting. The investigator who does not expand the context to include other environments may not discover the functional incapacity that the person with traumatic brain injury often exhibits in less structured settings.

You are interested in examining the functional capacities of persons with traumatic brain injuries. If the context for the study is functional capacity in a clinical setting, the informant may be maximally functional in this particular setting. The investigator who does not expand the context to include other environments may not discover the functional incapacity that the person with traumatic brain injury often exhibits in less structured settings. Consider a situation in which you are a regular reader of a “listserv” devoted to the discussion of disability rights and are examining the texts of postings to determine how rights are conceptualized and experienced. As a regular “lurker,” you are knowledgeable about the lives and experiences of those who post. However, you must be careful to identify this information as different from analysis of the actual posted texts as you analyze the textual data for meanings. Moreover, as an insider, you will also need to analyze how your understandings, biases, values, and experiences influence your interpretation of Web-based text.

Consider a situation in which you are a regular reader of a “listserv” devoted to the discussion of disability rights and are examining the texts of postings to determine how rights are conceptualized and experienced. As a regular “lurker,” you are knowledgeable about the lives and experiences of those who post. However, you must be careful to identify this information as different from analysis of the actual posted texts as you analyze the textual data for meanings. Moreover, as an insider, you will also need to analyze how your understandings, biases, values, and experiences influence your interpretation of Web-based text. You want to conduct a study in a medical setting. To gain access, initially it will be important to discuss the nature of your study with the directors of the departments you want to include. This discussion will be followed by a more normal introduction to medical personnel in staff meetings.

You want to conduct a study in a medical setting. To gain access, initially it will be important to discuss the nature of your study with the directors of the departments you want to include. This discussion will be followed by a more normal introduction to medical personnel in staff meetings.