Human resource management

Rebecca J. Harmon and Wesley M. Rohrer III.

Objectives

• List and explain the human resource management responsibilities of all managers.

• Implement effective strategies for building a health information management team.

• Describe orientation and training needs for health information services departments.

• Define and explain career planning programs for health information management personnel.

Key words

Affirmative action programs

Behaviorally anchored rating scales

Cafeteria benefit plan

Career counseling

Career planning

Compensation management

Counseling and referral

Critical incident method

Employee assistance program

Employee handbook

Employment at will

Equal employment opportunity

Factor comparison

Flex time

Graphic rating scales

Grievance procedure

Halo effect

Human resource audit

Job analysis

Job description

Job evaluation

Job grading

Job performance standards

Job ranking

Job sharing

Key indicators of demand

Layoffs

Management by objectives

Performance appraisal

Point system

Power

Preventive discipline

Progressive discipline

Reasonable accommodation

Recruitment pool

Replacement charts

Selection process

Self-appraisal

Sexual harassment

Staffing table

Strategic human resource planning

Transactional leadership

Transformational leadership

Undue hardship

Values clarification

Abbreviations

ADA—Americans with Disabilities Act

ADEA—Age Discrimination in Employment Act

AFL-CIO—American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations

AHIMA—American Health Information Management Association

BARS—Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales

BFOQ—Bonafide Occupational Qualification

BLS—Bureau of Labor Statistics

CEO—Chief Executive Officer

CQI—Continuous Quality Improvement

EAP—Employee Assistance Program

EEO—Equal Employment Opportunity

EEOC—Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

ERISA—Employee Retirement Income Security Act

FLSA—Fair Labor Standards Act

FMCS—Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service

FMLA—Family and Medical Leave Act

FTE—Full-Time Equivalent

HIM—Health Information Management

HIPAA—Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

HIS—Health Information Services

HMO—Health Maintenance Organization

HRM—Human Resource Management

IRCA—Immigration Reform and Control Act

ISO—International Standards Organization

JCAHO—Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (now the Joint Commission)

LAN—Local Area Network

MBO—Management By Objectives

NLRA—National Labor Relations Act

NLRB—National Labor Relations Board

OFCCP—Office of Federal Contract Compliance Program

OSHA—Occupational Safety and Health Administration/Act

PHI—Personal Health Information

POS—Point of Service

PPO—Preferred Provider Organization

QWL—Quality of Work Life

SEIU—Service Employees International Union

SQC—Statistical Quality Control

TQM—Total Quality Management

WAN—Wide Area Network

Student Study Guide activities for this chapter are available on the Evolve Learning Resources site for this textbook. Please visit http://evolve.elsevier.com/Abdelhak.

When you see the Evolve logo  , go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

, go to the Evolve site and complete the corresponding activity, referenced by the page number in the text where the logo appears.

Human resource management

Navigating through turbulent times

As we settle into a 21st-century mind-set, we would be wise to reflect on the dramatic changes in organization structure, technology, incentive structure, and strategies that have occurred in health care over the past several decades. Many of these changes can be classified as organizational responses to broad environmental influences that have had a pervasive impact across all industries and enterprises, including those in health care, rehabilitation, and long-term care. We have witnessed the emergence of the “informated” organization,1 the learning organization, the horizontal organization,2 the virtual organization, and the consumer-driven health care organization. Every manager, worker, and professional has been considerably affected by the explosion of access to information from links to local area networks (LANs) to wide area networks (WANs), data warehousing, and the virtually unlimited resources of the Internet. Benefits as well as excesses of reengineering have been chronicled and experienced by both the victims and survivors of corporate “downsizing” and outsourcing work to offshore sites. A bewildering variety of philosophies, methods, and buzzwords—continuous quality improvement (CQI), statistical quality control (SQC), total quality management (TQM), quality of work life (QWL), employee participation teams, empowerment, benchmarking, the Toyota manufacturing quality program, lean management, Baldridge awards, International Standards Organization (ISO) 9000, and Six Sigma certification among others—have competed for managerial and scholarly attention during this period of the transformation within the health care industry.

Broad environmental forces

Continuing challenges in the 21st century

Although the dawn of the new century will be forever marked in time with the events of September 11, 2001, a decade later, the rapidity with which change has settled on the United States, and indeed the world, continues to add complexity to societies great and small. Beyond the profound geopolitical, economic, religious, and cultural repercussions that the horrific events of September 11 exerted across the globe, less than a decade later, the world grapples with economic turmoil, emerging potential pandemics—real and forecasted—as well as a continuing shift in demographics that have forever changed business as usual. See Box 15-1 for ways 21st Century Issues have impacted society and the workplace. With the election of the first African-American president of the United States, the face of the American workforce—an important issue for the past 50 years—has changed.

The complexity and risk that all organizations face in this century of terror, economic uncertainty, and turmoil is exemplified by the increasing threat of pandemics (e.g., avian influenza A, H1N1). Although at this time it appears that the effects of H1N1 influenza will not be as severe as initially feared, the public health community nonetheless had to mobilize considerable resources to prevent the onset of a pandemic with global health and economic implications. Not only could such an epidemic have devastating effects on the health of populations (according to the World Health Organization, 30% of the world’s population might be affected in the first year of a pandemic, resulting in 2 million deaths),3 but it also would likely have severe, if temporary, effects on the economic, social, and political infrastructure. That the Harvard Business Review (May 2006) devoted a lengthy Special Report to alerting the business community to the importance of monitoring and planning for a pandemic is a telling indicator of the breadth and severity of the likely impact of such a public health assault on the individual organization and the corporate community. Clearly, because health care organizations will be on the front lines of addressing the consequences of a pandemic along with its public health partners, the organizational effects of such an event would almost certainly be immediate and profound. Although it is impossible to predict the future in detail, it is likely that the new level of heightened awareness, sense of insecurity, and vulnerability throughout the West will have long-lasting consequences in the workplace as well as across society.

The federal regulatory context

Although the pace of regulatory growth affecting human resource management (HRM) slowed somewhat after the explosion of legislative initiatives and regulatory mechanisms of the 1960s and 1970s, subsequent federal legislation continues to have a significant impact on the workplace. Most notable of these federal policies are the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993, and the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009. Although the ongoing elimination of legal and attitudinal barriers to women and minority participation in the workplace has led to formal recognition of diversity programs, in other arenas, the philosophical justification for equal employment opportunity (EEO) and especially affirmative action (AA) programs is being challenged. Beginning in 2006 with the Michigan Civil Rights Initiative in which Michigan voters overwhelmingly approved by ballot referendum limitation of the use of race as a preferential indicator for hiring, contracting, or admissions. The text from the ballot presented to voters describes the referendum issue as follows:

A proposal to amend the state constitution to ban affirmative action programs that give preferential treatment to groups or individuals based on their race, gender, color, ethnicity, or national origin for public employment, education, or contracting purposes.4

In short, no longer can certain groups get special status that would give them an advantage over others who do not possess that status. An advocate of legislation to prohibit AA as a legal principle and workplace practice would argue that ending carte blanche affirmative action is consistent with the original language of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 601, which states: “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” The Michigan Civil Rights Initiative takes this a step further editing in Section 26 of the Michigan Constitution: “The state shall not discriminate against or grant preferential treatment to any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education or public contracting” (ibid).

More recent judicial decisions in support of this trend include the June 2009 decision by the Supreme Court in Ricci vs. DeStefano, which found that white firefighters had been subjected to race discrimination when their promotions were overturned based solely on the fact that no black firefighters qualified for promotion based on test scores.5 These decisions and others add complexity to the decisions and constraints of the manager in today’s increasingly complicated workforce, and there are no indications that this trend will abate.

The demographic imperative

The phenomenon of an aging population is beginning to affect the workplace acutely, in the United States and other highly developed societies worldwide. This demographic trend, coupled with the legislative constraints on employer discretion embodied in the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA; 1967, as amended), has led to a “graying” of the workforce, at least in some regions of the United States. Also, the cultural and ethnic mix of workplaces in the United States and abroad are feeling the effects of sustained growth and migration. By mid-2007, the Hispanic population in the United States reached 41.3 million, growing almost 4% from the year before, and comprising just over 15% of the total U.S population.6

Although demographics continue to shift, other forces, like the steady erosion of union representation within the U.S. workforce (from 25% of the private sector workforce in 1973 to 7.6% in 2008),7 remain a major theme of labor relations through the end of the 20th century and into the 21st century. Although no major legislative developments have affected collective bargaining significantly during the past decade, recent political events portend significant changes in the near future. There have been continual skirmishes over management’s right to hire replacement workers and the ramifications of team participation in quality management efforts for traditional labor relations. However, the separation in 2005 of roughly 4 million members of three major collective bargaining structures, including the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO)8 posits a strong challenge for the future of organized labor. The long-term decline in union membership as a proportion of the workforce and the decline in political power of organized labor at least at the national level begs the question of whether traditional collective bargaining structures and processes will be able to adapt to and survive the environmental and workplace changes discussed.

Forces transforming health care

Beyond these broad influences affecting all organizations are the constellation of forces that have reshaped traditional health care and rehabilitation. The traditional model of health services delivery that focused on acute care (hospital) services and that was orchestrated by independent physicians has been radically transformed into an environment of competing managed care networks coordinating an array of linked services and settings across the continuum of care. “Managed care” includes an increasingly diverse set of institutional structures and affiliations, including the established health maintenance organizations (HMOs), physician provider organizations (PPOs), point-of-service (POS) agreements, integrated delivery systems, and other types of health plans and networks. A common element for managed care across these variations of organization design is the commitment to accept the financial and other risks of providing cost-effective services of high quality to enhance the health and well-being of a defined population. This commitment has resulted in priority given to aggressive cost control, organizational consolidation, system integration, market concentration, and image marketing on the basis of perceived differences in quality.

These rather profound changes in health care organization, provider incentives, and relationships among providers, consumers, and purchasers have had a considerable impact on HRM within health care and rehabilitation service organizations. As provider organizations have reduced staff to lower personnel costs, thereby increasing labor productivity in the short term, the potential for work-related stress, conflict, erosion of employee commitment and loyalty, and professional “burnout” has increased accordingly. Concomitantly, the implementation of new technologies, especially information technology, entails greater demands on employees to develop and continuously upgrade their skills and knowledge base to adapt to the plethora of information management tools and resources. Managers especially are faced with the pressures of maintaining their own professional and clinical competence while accommodating the new developments in information technology and information systems and adapting their leadership style and philosophy to the realities of changing employee values and expectations and to innovative structures (i.e., the horizontal, loosely linked, team-based organization).

The inevitability of change, if not of its specific forms or trajectory, is perhaps the only safe prediction about health care organization and delivery in the long term. Consequently, it can be argued that the most critical competencies of the health care manager and professional of the 21st century are the capacity to do the following:

Challenges for health information management professionals

Managing health information in the 21st century places special demands on health information management (HIM) professionals to obtain, train, retain, use, fully develop, and direct the efforts of the human resources required to achieve the goals of health care organizations. Several serious studies have concluded that the health care labor force of the future will demand multiskilled workers who have the flexibility of working in interdisciplinary teams in various provider settings within integrated health care systems and networks. Almost 20 years ago, the Pew Commission concluded that “the evolving nature of our health care system will require health professionals with different skills, attitudes and values . . . creating a growing demand for the skills of collaboration, effective communication and teamwork.”9 Health information managers, professionals, and technologists will be required to serve health care delivery systems that emphasize preventive, rehabilitative, and long-term care and will increasingly coordinate services across providers, disciplines, levels, and loci of care. As community-based and home health services expand, there will be increased demands for integration of clinical and financial data and capture of information relevant to various outcome measures at the individual patient or client level—that is, the health record—and aggregated at the service population or community level. In the presence of considerable uncertainty about exactly how health care will be organized and delivered in the next generation, it can be predicted with confidence that health information managers must be prepared to respond to accelerating changes in technology, public policy, competitive markets, population distribution, employee diversity, and organizational structures.

Leadership and human resources management

Leadership and management are closely related terms that convey different but complementary aspects of the behavior associated with ensuring effective organizational performance. Bennis and Nanus make the distinction in this way: “Managers are people who do things right and leaders are people who do the right things” (p. 221).10 One implicit difference suggested by this characterization is that managers focus on efficiency and control, whereas leaders focus on the “big picture” (i.e., communicating a vision of the organization and inspiring and influencing people to invest in achieving it). Both perspectives and the associated activities of working managers and leaders at all levels are necessary to sustain effective, high-performance organizations. Although this applies to all complex organizations, it might be argued that in no sector of society is the need for visionary leadership and effective management of organizational resources more important than in health care in the 21st century.

One of the most obvious but surprisingly complex questions is: “What is leadership, actually?” A massive volume of literature in leadership theory and practice has attempted to address this question during the past century, including controlled social science research studies and more descriptive, intuitive narratives from practicing leaders and executive managers. Some researchers have concluded, on the basis of a lack of reliable findings about the nature of leadership in thousands of studies, that its usefulness as a research variable may no longer be warranted. Nonetheless, common wisdom among practicing managers would suggest that leaders do make a difference in influencing the satisfaction, motivation, and achievements of their followers and in effecting organizational outcomes—even if the effects of leadership alone on desired outcomes are difficult to measure reliably. Most working professionals would agree that, even if they are not absolutely certain about what makes leaders effective, they know that we need effective leaders, especially when we face difficult challenges, rapid change, and crises.

Overview of leadership theory

A thorough review of the themes and models of leadership developed during the past 75 years would go beyond the limits of this chapter. However, an overview of the key themes and approaches to leadership should be useful in demonstrating the direct relevance of HRM to leadership. One basic difference in the evolving models of management has been the distinction between those that focus on the characteristics of leaders independent of other factors affecting leadership and those that emphasize leadership as a set of relationships. The former is the “trait” approach, which is based on the assumption that leadership could be fully explained by identifying a cluster of personality and character traits that are necessary and sufficient for the leader to be effective. Stogdill’s11 meta-analysis of many such studies found that there was little correlation among the various sets of traits, although some characteristics (e.g., intelligence, initiative, and self-confidence) were frequently identified.

Beyond the lack of agreement about a common and sufficient core of traits was the recognition that different situations seemed to call for different kinds of leadership. For example, the ideal leader for handling a true crisis (i.e., effective decision making under fire) may not necessarily have the best qualities for gaining commitment to a pervasive and long-term process of organization change. This contingency approach to leadership recognizes that other variables in the leadership situation or context are likely to influence the leader’s behavior and effectiveness. Among the variables identified in research studies using this model are the nature of the task, the expectations and maturity of followers, and the stability of the environment.12 One implication of a contingency approach to leadership is recognizing that what it takes to be an effective leader all depends on the situation the leader faces.

Relationships and leadership style

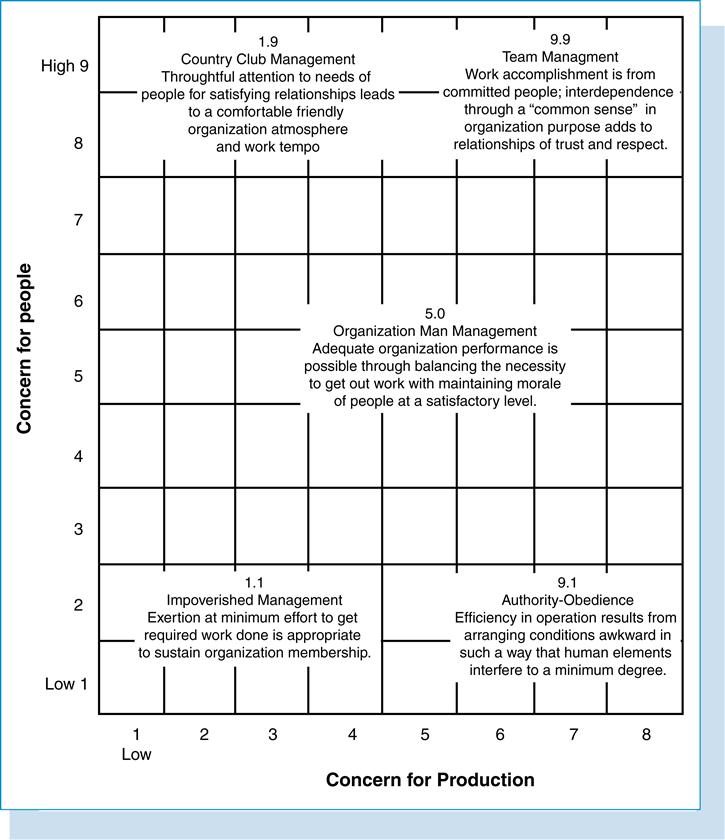

The fact that the nature of followers is recognized by the contingency approach as being an important variable suggests the importance of considering the relational nature of leadership. On one level, it is obvious that the concept of leadership entails that some others participate as followers. A credentialed health information manager might be an exceptionally competent and knowledgeable professional, but unless he or she has responsibility for directing the efforts of others, he or she is not a leader. So the aspect of relationship is inherent to a full understanding of leadership. This is also suggested by the leadership style approaches to leadership exemplified by the University of Michigan13 and Ohio State studies9 of leadership style or behavior. In both these classic studies, researchers attempted to determine which leadership styles were associated with effective group and organization performance. In these studies, two dimensions of leadership behavior were identified as characterizing different leadership styles: the Ohio State study identified these behavioral aspects as “initiating structure” and “consideration,” whereas in the Michigan State studies, the comparable dimensions were called “production orientation” and “employee orientation.” The first dimension focused on task behaviors and structuring and organizing work, whereas the second emphasized maintaining supportive relationships, especially between the leader (supervisor) and the followers (subordinates). These same dimensions are also the basis for the popular Managerial Grid, developed by Blake and McCanse,14 which describes five contrasting leadership styles (Figure 15-1).

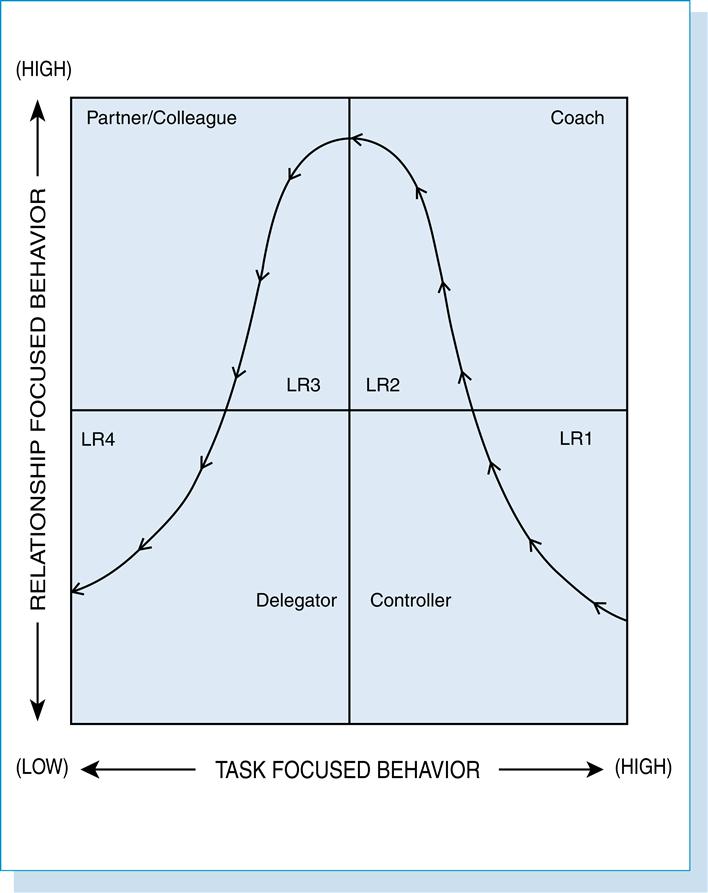

A more sophisticated and dynamic approach to leadership is the situational leadership model developed by Hersey and Blanchard,15 which builds on the task behavior and relationship behavior vectors. However, this model also incorporates a situational variable, the maturity of followers, to suggest which leadership style might be most appropriate in a given situation. The quadrants on the charts (see Leadership Roles Matrix) correspond to four distinctive leadership roles: controller, coach, partner/colleague, and delegator. The effectiveness of these roles, in terms of individual and team satisfaction and productivity, will depend on the degree of team development and maturity of the followers (Figure 15-2).

Although by no means conclusive, the leadership style studies collectively suggest that effective leaders generally are those who exhibit both a high concern for productivity and for people. Fiedler’s12 research linking leadership behavior to similar dimensions suggested that a structuring style was more appropriate when the leadership situation was either very favorable or very unfavorable to the leader, whereas a more people-oriented behavior was more appropriate when the leader faced ambiguous circumstances. What seems clear is that over the long term, the leader must attend to both production and people concerns to continue to be effective.

Human resource management can and should provide support to the operating manager to enhance his or her efforts in both domains. For example, effective employee recruitment and selection and job analysis processes can be useful tools in task structuring, whereas diversity management training can enhance the manager’s relational skills. Even a significant investment in the HRM function cannot guarantee effective leadership in the specific case, but without effective HRM processes, the manager may be at a distinct disadvantage. It could be argued that the more effective and efficient the HRM technical functions are, the more time and energy the manager should invest in his or her relationship-building activities with employees and peers.

Transformational leadership

Another useful perspective on leadership is that provided by Burns in his historical and psychological analysis of leadership.16 Burns contrasts two aspects or types of leadership: transactional and transformational. Transactional leadership refers to those behaviors associated with the more routine and continuing exchanges of effort and commitment between managers and employees in carrying out the business of the organization and sustaining effective working relationships. The transformational role of the leader refers to the visionary, motivational, and charismatic aspects of leadership. The transformational leader is able to articulate a vision of the organization’s future, to convince followers that they have a stake in the achievement of that vision, and to achieve commitment to change (personal and organizational) as not only inevitable but also beneficial both to the organization and to the employee’s self-interest. Schein17 focuses on the role of the leader as a change agent transforming organizational cultures by destroying dysfunctional ones and stimulating cultures supportive of growth and innovation. Hunt and Conger18 cite Tosi’s insistence that these aspects of leadership are complementary and necessary: “Supporting most successful charismatic/transforming leaders is their ability to effectively manage (transact with subordinates) the day-to-day mundane events that clog most leaders’ agendas. Without transactional leadership skills, even the most awe-inspiring transformational leader may fail to accomplish his or her intended mission.” Rohrer19 has proposed a third dimension, translational leadership, that allows for the effective communication of the charismatic vision into practice at the operating level, and that this aspect of leadership is an especially important responsibility of the middle manager as the key liaison between executive management and the first-line supervisory and operating staff. From this perspective the HRM director can be viewed as playing a “translational” role in establishing, communicating, and helping to implement HRM policies and procedures that support the strategic direction and goals of the health care organization.

Leadership development

Another aspect of leadership that has direct implications for HRM is that of emerging leadership and leadership development. If leadership is viewed primarily as being most characteristic of executive-level management, then leadership identification and development efforts are narrowly focused. However, if leadership is viewed as a capacity that is more widely distributed throughout the organization, the issues of emerging leadership and leadership development become more challenging and complex. Although a useful distinction has been made between management as a set of technical and control activities focused on maintaining day-to-day operations and the status quo in the short term and leadership as entailing a proactive, visionary, strategic, and empowering perspective, it could be argued that both aspects are required to some degree at all managerial levels in the organization. Health care organizations present additional challenges in this respect because of the professional specializations that go with the territory so that each health professional is subject to the claims and influences of both clinical and administrative leaders. Both training and development and performance appraisal functions within HRM should play a critical role in leadership development at the lower and middle management levels, including the early identification of potential leaders as executive managers from lower in the ranks.

The ethics of leadership

Although not necessarily recognized as an HRM responsibility, the development of ethically responsible managers and leaders has profound implications for HRM. A justification for serious consideration of the ethical dimension of leadership, specifically in health care, is expressed by Darr20: “For the health services manager, a personal ethic is a moral framework for relationships with employees, patients, organization, and community. In these relationships, the manager is not, and cannot be, a morally neutral technocrat. The manager is a moral agent” (p. 1). What follows from Darr’s claim is that all managerial behavior—at least all activity that is relational rather than purely technical—must be considered from an ethical or moral perspective. This also entails that ethical decision making is complicated by the fact that the manager must consider his or her decisions in terms of the interests of various constituency groups. Burns’s16 theory of transformational leadership also places the ethical dimension at the core of leadership in that it is rooted in individual, organizational, and societal values. He contends that “transforming leaders ‘raise’ their followers up through levels of morality” (p. 426). He notes that transformational leaders are more concerned about “end values” such as justice and equality, whereas transactional leaders focus more on modal (means) values such as honesty and fairness. Characteristic of both types of leadership is the leader’s role in serving a common purpose that transcends individual needs and interests of the leader and the followers.

Normative ethics may be defined as the science or art of determining principles, rules, and guidelines for right conduct (i.e., how one should behave responsibly in the community). For example, the preamble to the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) Code of Ethics (2004) states21:

The ethical obligations of the HIM professional include the protection of patient privacy and confidential information; disclosure of information; development, use, and maintenance of health information systems and health records; and the quality of information. Both handwritten and computerized medical records contain many sacred stories—stories that must be protected on behalf of the individual and the aggregate community of persons served in the health care system. Health care consumers are increasingly concerned about the loss of privacy and the inability to control the dissemination of their protected information. Core health information issues include what information should be collected, how the information should be handled, who should have access to the information, and under what conditions the information should be disclosed.

Ethical obligations are central to the professional’s responsibility, regardless of the employment site or the method of collection, storage, and security of health information. Sensitive information (genetic, adoption, drug, alcohol, sexual, and behavioral information) requires special attention to prevent misuse. Entrepreneurial roles require expertise in the protection of the information in the world of business and interactions with consumers.

It would be difficult to argue with this statement of ethical accountability—and these standards—for HIM professionals could be applied to all health care professionals and managers through the health care system. Yet what specifically are the exemplary values that are to ground and guide ethical behavior in health care? Although numerous lists of values have been presented as core or fundamental to ethically responsive behavior in health care, the following have achieved a broad consensus as prima facie ethical duties.

Respect for person

This value entails regarding each person (patient, subordinate, boss, peer, neighbor) as an end in himself or herself rather than as a means to some end or as an impersonal stereotype. This value entails granting the other person the maximum freedom that the nature of the relationship allows without impairing the freedom or welfare of others.

Beneficence (service)

This value represents a commitment to doing good for, or providing service to, the other person, community, or broader society. A disposition toward competent, caring service to specific individuals (e.g., clients) or the broader community seems to be intrinsic in the health care professions. Although the focus of the direct care provider, physician, or therapist is usually on the health and well-being of the individual patient, the health care manager must also consider the effects of his or her decisions on the organization, the population or community it serves, and the broader society, including the global impact, if any. That the interests of the individual and the community may differ and cause conflict is a challenge faced often by the ethically responsive public health professional.

Nonmaleficence

This value forbids the ethically responsive person from doing harm or injury to the person or welfare of another. In one sense, this represents the other side of the coin of the duty to do good. This is represented by the Hippocratic oath, which indicates that the physician’s primary responsibility is to “do no harm.” Like beneficence, this value challenges the ethical manager to consider and balance the needs and interests of all his or her key constituencies in making decisions with ethical consequences.

Justice

Often regarded as synonymous with fairness, acting justly in practice is almost always more complex than it appears. A more elaborate definition of justice is ensuring that equals are treated equally, whereas “unequals” may be treated differentially. For example, all patients presenting with diabetes symptoms at the same stage of the disease should be given equivalent (if not strictly identical) treatment by the physician. However, if two patients present in an emergency department at the same time, the one with massive head trauma from an automobile accident should be given priority attention over the patient with a broken toe. The grounds for making these distinctions are addressed in discussion of the concept of distributive justice. For example, if the manager is allocating the end-of-year salary increases, which factors should be given most weight-past performance, recent acquisition of new skills, seniority, or some other consideration?

Other core values in health care management

Northouse22 adds two other values critical to leadership that are certainly worth consideration: honesty and building community. A compelling argument could be made that honesty or truth telling is a bedrock value on which all others are founded. Certainly our entire social fabric and the stability and integrity of our organizational culture depends on the assumption that most people, most of the time, are telling the truth as they see it. Without this ethical foundation, we could not make any reliable assumptions about the link between intentions, speech, and behavior of ourselves or of those with whom we interact. Honesty is not only the best policy ethically; it is the only reasonable basis for group behavior, organizational effectiveness, and managerial decision making in the long run.

If honesty is seen as a necessary precondition for ethical behavior, community building may be viewed as an outcome of ethical leadership. Northouse22 argues that ethical leadership requires a community-oriented perspective. “Transformational leaders and followers begin to reach out to wider social collectivities and seek to establish higher and broader moral purposes . . . An ethical leader is concerned with the common good—in the broadest sense” (p. 316). Implicit in this statement is that ethical leaders will attempt to align their actions to the extent possible with the good of the community and broader society. For example, the board of directors and executive management team of a hospital should consider the impact of a potential relocation of the facility from the urban core to a growing suburb on both communities affected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree