Collecting Information

Key terms

Artifact review

Closed-ended question

Hawthorne effect

Interviews

Materials

Observation

Open-ended question

Probes

Questionnaires

Secondary data analysis

Structured interview

Unobtrusive methodology

Unstructured interview

You now have a better understanding of the methods for involving individuals, events, observations, and artifacts in your study. Now let us explore the various strategies you can use to collect information or data. This chapter provides an overview of the action process of gathering information to answer research questions or queries. A number of strategies are discussed, some of which are used exclusively in experimental-type research or in naturalistic inquiry. Subsequent chapters examine the specific approaches used in each research tradition.

In experimental-type research, data collection is a distinct action phase that represents the crossroads between the thinking processes involved in question formation, development and implementation of design, and the action process of analysis. Strategies for data collection involve actions that are pertinent to the research problem and consistent with the design. In turn, the types of data collected and the methodological approach used to obtain information shape both the type and nature of the analytical process and the understandings and knowledge that can emerge.

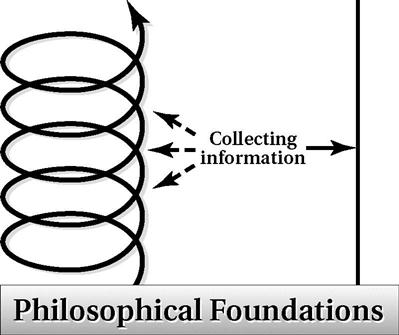

In naturalistic inquiry, gathering information stems from the initial query. However, it is embedded in an iterative, abductive approach that involves ongoing analysis, reformulation, and refinement of the initial query.

Principles of information collection

Three basic principles characterize the process of collecting information within the different research traditions (Box 15-1).

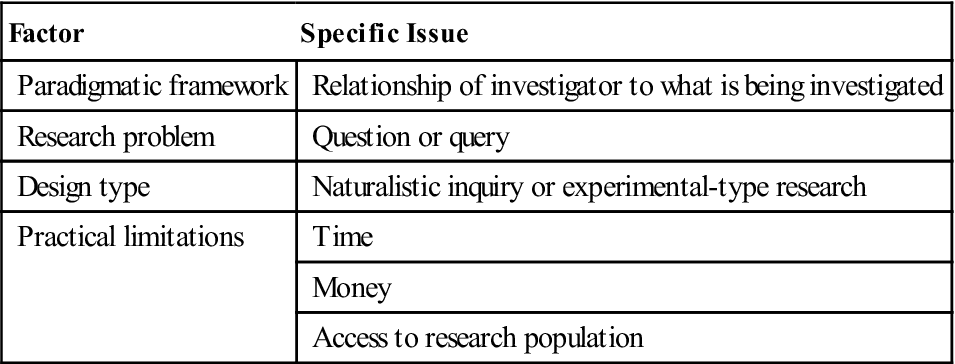

First, the aim of collecting information, regardless of how it is conducted, is to obtain data that are both relevant and sufficient to answer a research question or query. Second, the choice of a data collection or information-gathering strategy is based on four major factors: the researcher’s paradigmatic framework, the nature of the research problem, the type of design, and the practical limitations or resources available to the investigator (Table 15-1). Third, although the overall data collection strategy reflects the researcher’s basic philosophical perspective, a specific procedure, such as observation or interview, may be used by researchers conducting either a naturalistic or an experimental-type study. Many researchers find it useful to collect data and information with more than one procedure or technique to be able to answer a question or query more fully. The use of multiple collection techniques is referred to as “triangulation” or “crystallization” and is useful for increasing the accuracy of information.1 We discuss this technique in subsequent chapters.

Table 15-1

Factors Influencing Choice of Strategy for Collecting Information

| Factor | Specific Issue |

| Paradigmatic framework | Relationship of investigator to what is being investigated |

| Research problem | Question or query |

| Design type | Naturalistic inquiry or experimental-type research |

| Practical limitations | Time |

| Money | |

| Access to research population |

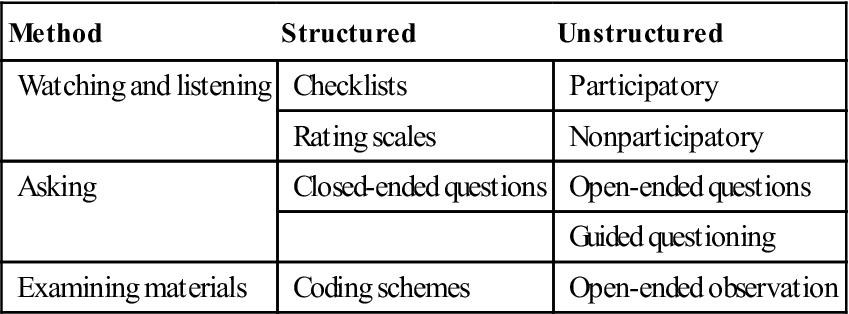

In general, the action process of data and information collection uses one or more of the following strategies: (1) looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording; (2) asking; and (3) obtaining and examining materials. Each of these strategies can be structured, semistructured, or open-ended, depending on the nature of the inquiry (Table 15-2). Also, each strategy can be used in combination with another.

Table 15-2

Summary of Strategies for Collecting Information

| Method | Structured | Unstructured |

| Watching and listening | Checklists | Participatory |

| Rating scales | Nonparticipatory | |

| Asking | Closed-ended questions | Open-ended questions |

| Guided questioning | ||

| Examining materials | Coding schemes | Open-ended observation |

Looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording

One important data collection and information-gathering strategy involves systematic observation. The process of observation includes five primary activities, which may be interrelated: looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording. The record produced by the investigator comprises the data set. The way in which the researcher looks, watches, reads, and listens may range from being structured to unstructured, participatory to nonparticipatory, narrowly to broadly focused, and time limited to ongoing and fully immersed.2

In the experimental-type tradition, observation is usually time limited and structured. Criteria to look, watch, listen, read, and record are determined a priori to gathering data, and the data are recorded as a structured measurement system. For example, checklists may be used that indicate the frequency (or only the presence or absence) of a particular behavior or object under study. Or a text may be read, and the occurrences of a particular phrase to denote “power language” might be counted and recorded. Phenomena other than those specified before entering the field are omitted from or remain outside the investigator’s record. Rating scales may also be used to record observations; the investigator rates the observed phenomenon on a scale with a predetermined point system (see Chapter 16).

Looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording take on an inductive quality in naturalistic designs, with varying degrees of participation and interaction between the investigator and the phenomena of interest. The investigator broadly defines the boundaries of observation (e.g., a community health center), then moves to a more focused observational approach (e.g., particular locations, navigation patterns, staff–client interactions, language, signs, images) as the process of collecting and analyzing information from previous observations unfolds.

Asking

Health and human service providers routinely ask a wide range of questions to obtain information for professional purposes. Similarly, in research, “asking” is a systematic and purposeful aspect of a data collection plan. As in observation, questions can vary in structure and content, from unstructured and open-ended questions to structured and closed-ended questions or fixed-response queries that use a predetermined response set.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Let us examine the concept of “intelligence” to illustrate different observational approaches. In experimental-type studies, intelligence testing relies largely on the use of a structured instrument that involves paper-and-pencil or computer-based tests and a tester observing a subject’s performance in a laboratory setting. Measurements are obtained on dimensions that have been predefined as composing the construct of intelligence. Typically, a score or set of scores will denote the magnitude of an individual’s intelligence. In a naturalistic approach, however, rather than using predefined criteria, the investigator may watch and listen to persons in their natural environments to reveal the meaning of intelligence and the ways it is recognized and responded to in a particular culture. Each approach has its value in addressing specific types of research questions or queries. Structured observation of intelligence is appropriate for the investigator who wants to compare populations or individuals, measure individual or group progress and development, or describe population parameters on a standard indicator of intelligence. In contrast, naturalistic observation of intelligence is useful to the researcher attempting to develop new understandings of the construct.

Let us examine the concept of “intelligence” to illustrate different observational approaches. In experimental-type studies, intelligence testing relies largely on the use of a structured instrument that involves paper-and-pencil or computer-based tests and a tester observing a subject’s performance in a laboratory setting. Measurements are obtained on dimensions that have been predefined as composing the construct of intelligence. Typically, a score or set of scores will denote the magnitude of an individual’s intelligence. In a naturalistic approach, however, rather than using predefined criteria, the investigator may watch and listen to persons in their natural environments to reveal the meaning of intelligence and the ways it is recognized and responded to in a particular culture. Each approach has its value in addressing specific types of research questions or queries. Structured observation of intelligence is appropriate for the investigator who wants to compare populations or individuals, measure individual or group progress and development, or describe population parameters on a standard indicator of intelligence. In contrast, naturalistic observation of intelligence is useful to the researcher attempting to develop new understandings of the construct. An example of an open-ended question is, “How have you have been feeling this past week?” or “How is it now for you compared with before your stroke?” In contrast, an example of a structured or closed-ended question is, “In this past week, how would you rate your health: excellent, good, adequate, fair, or poor?”

An example of an open-ended question is, “How have you have been feeling this past week?” or “How is it now for you compared with before your stroke?” In contrast, an example of a structured or closed-ended question is, “In this past week, how would you rate your health: excellent, good, adequate, fair, or poor?”