An Overview of Growth, Development, and Nutrition

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

2. Explain the differences between growth, development, and maturation.

3. Recognize and read a growth chart for children.

4. List five factors that influence growth and development.

5. Discuss the nursing implications of growth and development.

6. Discuss the importance of family-centered care in pediatrics.

8. Describe three developmental theories and their impact on planning the nursing care of children.

9. Discuss the nutritional needs of growing children.

10. Differentiate between permanent and deciduous teeth, and list the times of their eruption.

11. Understand the characteristics of play at various age levels.

12. Describe the relationship of play to physical, cognitive, and emotional development.

13. Understand the role of computers and computer games in play at various ages.

Key Terms

adolescent (p. 350)

cephalocaudal (sĕf-ă-lō-KĂW-dăl, p. 350)

cognition (kŏg-NĬ-shŭn, p. 364)

community (p. 357)

competitive play (p. 383)

cooperative play (p. 383)

deciduous (dĕ-SĬD-ū-ŭs, p. 380)

dysfunctional family (p. 357)

Erikson’s stages (p. 366)

extended family (p. 356)

fluorosis (flū-RŌ-sĭs, p. 381)

growth (p. 350)

height (p. 350)

infant (p. 350)

Kohlberg (p. 366)

length (p. 350)

Maslow (p. 364)

maturation (p. 350)

metabolic rate (p. 352)

neonate (p. 349)

nuclear family (p. 356)

nursing caries (p. 381)

parallel play (p. 383)

personality (p. 364)

Piaget (pē-ă-ZHĀ, p. 364)

preschool (p. 350)

proximodistal (prŏk-sĭ-mō-DĬS-tăl, p. 350)

school-age (p. 350)

therapeutic play (p. 383)

toddler (p. 350)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

Growth and Development

The main difference between caring for the adult and caring for the child is that the latter is in a continuous process of growth and development. This process is orderly and proceeds from the simple to the more complex (Box 15-1). Although the process is orderly, it is not steadily paced. Growth spurts are often followed by plateaus. One of the most noticeable growth spurts is at the time of puberty. The rate of growth varies with the individual child. Each infant has an individual timetable that revolves around established norms. Siblings within a family vary in growth rate. Growth is measurable and can be observed and studied. This is done by comparing height, weight, increase in vocabulary, physical skills, and other parameters. There are variations in growth within the systems and the subsystems. Not all parts mature at the same time. Skeletal growth approximates whole-body growth, whereas the brain, lymph, and reproductive tissues follow distinct and individual sequences.

The Impact of Growth and Development on Nursing Care

Pediatrics is a subspecialty of medical-surgical nursing. Adult acute care units in a hospital may contain a separate neurology unit, a separate cardiac unit, a separate medical unit, and a separate surgical unit. On the pediatric acute care unit in the general hospital, all medical-surgical specialties are usually housed on one unit—for patients from newborn to adolescent. The developmental needs of the child have an impact on his or her response to illness and on the approach the nurse must take in developing a plan of care. Choosing the right words to explain to a child what will happen is essential. For example, if the nurse states that the child will be “put to sleep” before the operation, will the child relate that to a pet at home being “put to sleep” and never heard from again? The fractured jaw of an 8-month-old after a motor vehicle accident may affect his developmental process more seriously than the same injury in a 4-year-old, because the 8-month-old is in the oral phase of development.

Because the child differs from the adult both anatomically and physiologically, differences in response to therapy as well as in manifestations of illness can be anticipated. The nurse must understand the normal to recognize deviations within any age-group and to plan care that takes these developmental differences into consideration (Box 15-2).

An understanding of growth and development, including its predictable nature and individual variation, has value in the nursing process. Such knowledge is the basis of the nurse’s anticipatory guidance of parents. For example, the nurse who knows when the infant is likely to crawl can, at the appropriate age, expand teaching on safety precautions. The nurse also incorporates these precautions into nursing care plans in the hospital. Age-appropriate care cannot be administered without an understanding of growth and development.

While explaining various aspects of child care to families, the nurse stresses the importance of individual differences. Parents tend to compare their children’s development and behavior with those of other children and with information in popular magazine articles. This may relieve their anxiety or cause them to impose impossible expectations and standards. In addition, many parents had poor role models who influenced their own experiences as children. Lack of knowledge about parenting can be recognized by the nurse and suitable interventions begun.

The nurse who understands that each child is born with an individual temperament and “style of behavior” can help frustrated parents cope with a newborn who has difficulty settling into the new environment. Specific parameters can be used to determine whether an infant is merely on an individual timetable or whether the infant varies from normal.

The nurse must also recognize when to intervene to prevent disease and/or accidents. For example, a brief visit with a caregiver may reveal that the child’s immunizations are not up to date. A review with a teenage mother of the characteristics of a 2-year-old may prevent the ingestion of poisons. Complications of the newborn can be avoided by advising the expectant mother to avoid alcohol and cigarettes. Other threats to health may likewise be anticipated. Knowing that specific diseases are prevalent in certain age-groups, the nurse maintains a high level of suspicion when interacting with these patients. This approach, based on developmental knowledge, experience, and effective communication, helps to ensure a higher level of family care. Finally, the nurse must understand how to provide nursing care to children of various ages to enhance their physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual development according to their specific needs and comprehension.

Terminology

The following stages of growth and development are referred to throughout this text:

Growth refers to an increase in physical size and is measured in inches and pounds. Development refers to a progressive increase in the function of the body. These two terms are inseparable. Maturation (maturus, “ripe”) refers to the total way in which a person grows and develops, as dictated by inheritance (Box 15-3). Although maturation is independent of environment, its timing may be affected by environment.

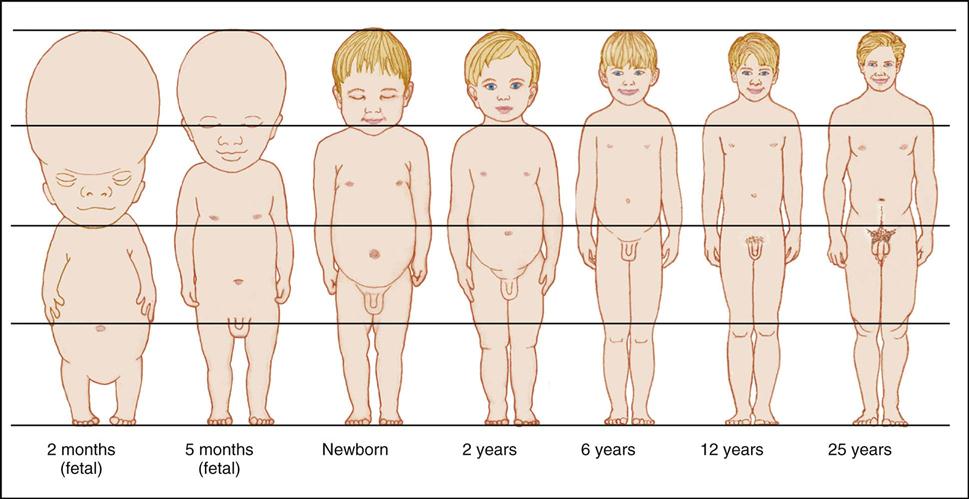

Directional Patterns

Directional patterns are fundamental to all humans. Cephalocaudal development proceeds from head to toe. The infant is able to raise the head before being able to sit, and he or she gains control of the trunk before walking. The second pattern is proximodistal, or from midline to the periphery. Development proceeds from the center of the body to the periphery (Figure 15-1). These patterns occur bilaterally. Development also proceeds from the general to the specific. The infant grasps with the hands before pinching with the fingers.

Some Developmental Differences Between Children and Adults

Height

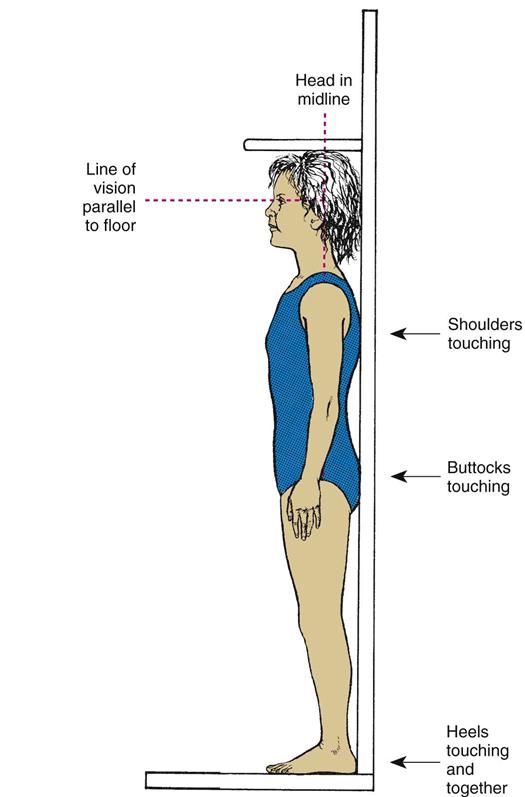

Height refers to standing measurement, whereas length refers to measurement while the infant is in a recumbent position. At birth the newborn has an average length of about 50 cm (20 inches). Linear growth is caused mainly by skeletal growth. Growth fluctuates until maturity is reached. Infancy and puberty are both rapid growth periods. Height is generally a family trait, although there are exceptions. Good nutrition and general good health are instrumental in promoting linear growth. Height is measured during each well-child visit (Skill 15-1). The length of the infant usually increases about 2.5 cm (1 inch) per month for the first 6 months. By age 1 year, the birth length increases by 50% (mostly in the trunk area).

Weight

Weight is another good index of health. However, the weight of a newborn infant does not always imply gestational maturity (see Chapter 13 and Figure 13-1). The average full-term newborn weighs 2.72 to 4.08 kg (6 to 9 lb), with an average of 3.4 kg (7.5 lb). Approximately 5% to 10% of the birth weight is lost by age 3 or 4 days as the result of the passage of stools and a limited fluid intake. The infant usually regains his or her birth weight by age 10 to 12 days. Birth weight usually doubles by age 5 to 6 months and triples by age 1 year. After the first year, weight gain levels off to approximately 1.81 to 2.72 kg (4 to 6 lb) per year, until the pubertal growth spurt begins.

Weight is determined at each office visit. A marked increase or decrease necessitates further investigation. The body weight of a newborn is composed of a higher percentage of water than in the adult. This extracellular fluid falls from 40% in the newborn to 20% in the adult. The high proportion of extracellular fluid in the infant can cause a more rapid loss of total body fluid, and therefore every infant must be closely monitored for dehydration. (See technique of weighing infants in Chapter 12 and Figure 12-11.)

Body Proportions

Body proportions of the child differ greatly from those of the adult (Figure 15-2). The head is the fastest-growing portion of the body during fetal life. During infancy the trunk grows rapidly, whereas during childhood, growth of the legs becomes the predominant feature. At adolescence, characteristic male and female proportions develop as childhood fat disappears. Alterations in proportions in the size of head, trunk, and extremities are characteristic of certain disturbances. Routine measurements of head and chest circumference are important indices of health.

Metabolic Rate

The metabolic rate (energy utilization and oxygen consumption) is higher in children than in adults. Infants require more calories, minerals, vitamins, and fluid in proportion to weight and height than adults. Higher metabolic rates are accompanied by an increased production of heat and waste products. The body surface area (BSA) of young children is far greater in relation to body weight than that of adults. The young child loses relatively more fluid from the pulmonary and integumentary systems.

Respirations

The respirations of infants are irregular and abdominal. Small airways can become easily blocked with mucus. The short, straight eustachian tube connects with the ear and predisposes the infant to middle ear infections. The chest wall is thin, and the muscles are immature, and therefore pressure on the chest can interfere with respiratory efforts.

Cardiovascular System

In neonates, the muscle mass of the right and left ventricles of the heart is almost equal. An increased need for cardiac output is often met by an increase in heart rate. Newborns have a high oxygen consumption and require a high cardiac output in the first few months of life. The presence of fetal (immature) hemoglobin in the first months of life also contributes to the need for a high cardiac output. The disappearance of fetal hemoglobin along with the loss of maternal iron stores contributes to the development of physiological anemia in infants after 3 or 4 months of age.

Immunity

For the first 3 months of life, the newborn is protected from illnesses to which the mother was exposed. The infant gradually produces his or her own immunoglobulin, until adult levels are reached by puberty. Therefore the infant and child must be protected from health care–associated infections in the hospital and from unnecessary exposure to pathogens. Immunizations against common childhood communicable diseases are discussed in Chapter 32.

Kidney Function

Kidney function is not mature until the end of the second year of life. Therefore drugs that are eliminated via the kidney can accumulate in the body to dangerous levels before age 2 years. Immature kidney function also predisposes the infant to dehydration. Nursing responsibilities for children under age 2 years include monitoring for dehydration and observing closely for toxic effects of drug therapy.

Nervous System

Maturation of the brain is evidenced by increased coordination, skills, and behaviors in the first years of life. Primitive reflexes, such as the grasp reflex, are replaced by purposeful, controlled movement. Head circumference increases 1.5 cm (0.6 inch) per month to an approximate total of 43 cm (17 inches) at age 6 months. During the second 6 months of life, head circumference increases 0.5 cm (0.2 inch) per month to an approximate total of 46 cm (18 inches) at 1 year of age. The age-appropriate toy is correlated with nervous system maturation. When selecting play activities, the nurse should consider the diagnosis and the child’s developmental level and abilities to be sure the toy is safe.

Sleep Patterns

Sleep patterns vary with age. The neonate sleeps 8 to 9 hours per night and naps an equal amount of time during the day. The 2-year-old may sleep 10 hours during the night and have only one short daytime nap. The 7-year-old usually requires 11 to 13 hours of sleep and rarely has a daytime nap. These patterns may be altered by cultural practices. For example, Israeli kibbutzim often have all family members nap after work or school, before dinner.

Bone Growth

Bone growth provides one of the best indicators of biological age. Bone age can be determined by x-ray studies. In the fetus, bones begin as connective tissue, which later is converted to cartilage. Cartilage is converted to bone through ossification. The rate of bone growth and the age of maturity vary within individuals, but the progression remains the same. Growth of the long bones continues until epiphyseal fusion occurs. Bone is constantly synthesized and resorbed. In children, bone synthesis is greater than bone destruction. Calcium reserves are stored in the ends of the long bones. Vitamin A, vitamin D, sunlight, and fluorine are necessary for the growth and development of skeletal and soft tissue.

Critical Periods

There appear to be certain periods when environmental events or stimuli have their maximum impact on the child’s development. The embryo, for example, can be adversely affected during times of rapid cell division. Certain viruses, drugs, and other agents are known to cause congenital anomalies during the first 3 months after conception. It is believed that issues such as developing a sense of trust during the first year of life and learning readiness are also subject to these periods of particular sensitivity.

Integration of Skills

As the child learns new skills, they are combined with those previously mastered. The child who is learning to walk may sit, pull the body up to a table by grasping it, balance, and take a cautious step. Tomorrow the child may take three steps! Children connect and perfect each skill in preparation for learning a more complex one.

Growth Standards

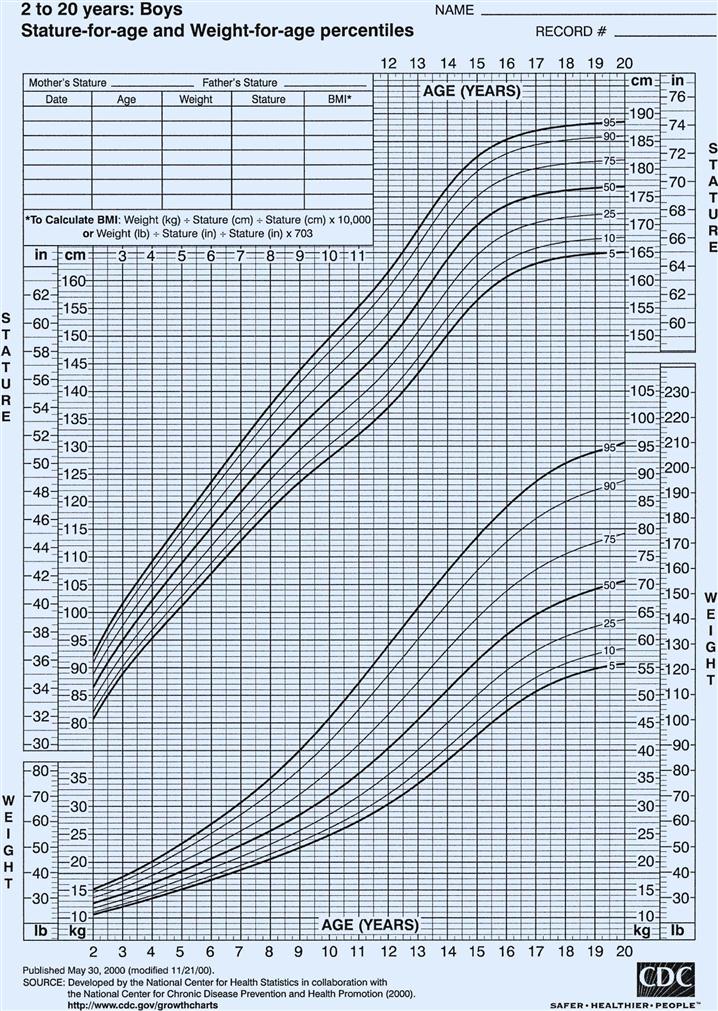

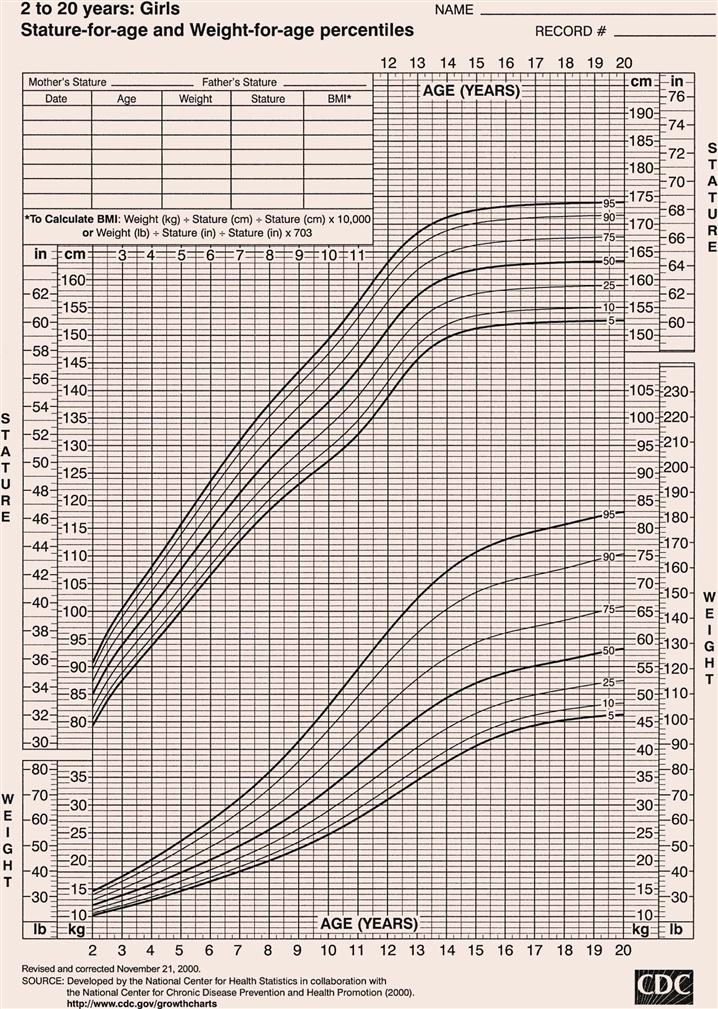

Growth is measured in dimensions such as height, weight, volume, and thickness of tissues. Measurement alone, without any standard of comparison, limits the interpretation of the data. A number of standards have been developed to make it possible to compare (1) the measurement of a child to others of the same age and sex (and, ideally, race), and (2) the child’s present measurements with the former rate of growth and pattern of progress. These standards, available as growth charts, are among the tools that have been used to assess the child’s overall development (Figure 15-3).

Length refers to horizontal measurement; it is used before a child can stand, usually from birth to 2 years. Height is measured with the child standing, usually between 2 and 18 years. Some pointers in reading and interpreting growth charts are as follows:

Developmental Screening

Developmental screening is a vital component of child health assessment. One widely used tool is the Denver II, a revision of the Denver Developmental Screening test. This tool assesses the developmental status of children during the first 6 years of life in four categories: personal-social, fine motor-adaptive, language, and gross motor. It is not an intelligence test. Its purpose is to identify children who are unable to perform at a level comparable to their age-mates. A low score merely indicates a need for further evaluation. It is designed for use by both professionals and paraprofessionals. Proper administration and interpretation will aid in developing an individualized plan of care for the child.

Influencing Factors

Growth and development are influenced by many factors, such as heredity, nationality, race, ordinal position in the family, gender and environment. These factors are closely related and dependent on one another in their effect on growth and development. They make each person unique. If a child is ill, physically or emotionally, the developmental processes may be delayed.

Hereditary Traits

Characteristics derived from our ancestors are determined at the time of conception by countless genes within each chromosome. Each gene is made of a chemical substance called deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which plays an important part in determining inherited characteristics. Examples of inherited traits are eye color, hair color, and physical resemblances within families.

Nationality and Race

Many physical differences among people of various nationalities and races, who were formerly distinguished with ease, have become less apparent in our age of common environment and customs. For instance, a person of Japanese origin might be thought of as being of short stature. However, Japanese children living in the United States are comparable in height to other children in this country. Nevertheless, ethnic differences extend into many areas including speech, food preferences, family structure, religious orientation, and code of conduct. The nurse should ascertain cultural beliefs and practices when collecting data for nursing assessment (see Table 15-2 on pp. 358–364).

Ordinal Position in the Family

Whether the child is the youngest, the middle, or the oldest in the family has some bearing on growth and development. The youngest and middle children learn from their older sisters and brothers. However, motor development of the youngest may be prolonged if the child is babied by the others in the family. The only child or the oldest child may excel in language development because his or her conversations are mainly with adults. These children are often the object of greater parental expectations.

Gender

The male infant often weighs more and is slightly longer than the female. He grows and develops at a slightly different rate. Parents and relatives may treat boys differently from girls by providing “gender-appropriate” toys and play and by having different expectations of them. Current trends promote unisex activities in play and career development.

Environment

The physical condition of the newborn is influenced by the prenatal environment. The health of the mother at the time of conception and the amount and quality of her diet during pregnancy are important for proper fetal development. Infections or diseases may lead to malformations of the fetus. A healthy and strong newborn can easily adapt to its surroundings.

The home greatly influences the infant’s physical and emotional growth and development. If a family is financially strained by an added member and the parents are unable to provide nourishing foods and suitable housing, the infant is directly affected. An uneducated mother may not know how to properly cook foods to preserve their nutritional value. Immunizations and other medical attention may be neglected. The infant senses tension within the family and is affected by it.

In contrast, energies can be directed toward positive development when the surroundings are secure and stable and the infant feels secure, wanted, and loved. Most environments are neither completely positive nor completely negative but fall somewhere between the two extremes. Intelligence plays an important role in social and mental development. Potential intelligence is thought to be inherited but greatly affected by the environment.

The Family

The family has been defined in many different ways and fulfills many different purposes. Generally, a family is defined as two or more person’s living and interacting together. Traditionally, the nuclear family, or biological family, has been the basic unit of structure in American society (mother, father, siblings). Today many nuclear families do not share the same household because of single parenthood, divorce, and remarriage. Kinship lines have become blurred, and fundamental changes from what was once perceived as standard are occurring in the family. The extended family refers to three generations: grandparents, parents, and children. Because of an increasing life span, however, there are a greater number of living grandparents and great-grandparents, and the proportion of them living in the family home may increase. Table 15-1 lists the various types of families and gives a description of each.

Table 15-1

| TYPE OF FAMILY* | DESCRIPTION |

| Nuclear | Traditional—husband, wife, children (natural or adopted) |

| Extended | Grandparents, parents, children, relatives |

| Single-parent | Women or men establish separate households through individual preference, divorce, death, illegitimacy, or desertion |

| Foster-parent | Parents who care for children requiring parenting because of a dysfunctional family, no family, or individual problems |

| Alternative | Communal family |

| Dual-career | Both parents work outside the home because of desire or need |

| Blended | Remarriage of persons with children |

| Polygamous | More than one spouse |

| Homosexual | Two persons of the same sex adopt children or have children from a previous marriage |

| Cohabitation | Heterosexual or homosexual couples live together but remain unmarried |

*Not all family types may be legally sanctioned. A family is two or more persons who live and interact together.

The interactions of family unit members are by far the most influential aspect of family life in the growth and development of the child. The nurse must understand the interaction of the family unit to be able to effect a positive change that may be necessary to prevent or treat childhood illnesses. Some families have solid support systems and use available community resources to maintain health. Other families may lack support systems and require closer follow-up care and encouragement by the health team. Parenting is a learned behavior, often modeled by past experience and modified by the acceptance of specific roles and responsibilities. A family that does not provide for the optimum physical, psychological, and emotional health of the children is called a dysfunctional family. A dysfunctional family does not necessarily imply that its members are not loving and caring. A dysfunctional family does not know how to be successful in its efforts and interactions and requires intervention.

Historically, in middle-class families the father was the breadwinner and the mother managed the home and raised the children. This model has shifted. Because of changing economic conditions, both parents’ earnings may be necessary to maintain the family’s standard of living. In dual-career families both the father and the mother are often absent for most of the day because of long commutes or the demands of the working environment. Both parents may share child care and domestic chores. The parents may need to transfer to different locations to maintain their careers. This decreases extended family support and makes it necessary for children to change schools frequently.

Divorce, separation, death, and pregnancy outside marriage create many one-parent families. The percentage of children living in single-parent families has more than doubled since the 1970s. Most single-wage families have an economic disadvantage, but families with women as the sole wage earner often have considerably lower incomes than those in which men are the sole wage earner. The problem of providing good, affordable child care is a serious one for both dual-career families and single parents. Relatives and the noncustodial parent may assist in raising the child. Many single parents remarry, creating the blended family. The addition may be merely a stepfather or stepmother, or two families may unite. These family units must make many adjustments. To succeed, parents and children have to learn problem-solving techniques, communication skills, and flexibility.

A family APGAR, first described by Smilkstein and colleagues (1984), is a tool that can be used as a guide to assess family functioning. This assessment is valuable in determining the approach to home care needs:

• Adaptation: How the family helps and shares resources

• Partnership: Lines of communication and partnership in the family

• Growth: How responsibilities for growth and development of child are shared

• Affection: Overt and covert emotional interactions among family members

• Resolve: How time, money, and space are allocated to prevent and solve problems

Questions concerning each of these areas should be posed and evaluated. The goal in family assessment is to enable the nurse to develop interventions that aid the family to achieve a healthier adaptation to the child’s health needs or problems.

The Family as Part of a Community.

The term community is defined in many ways, but here it is used to refer to the immediate geographical area in which the family lives and interacts (e.g., “I come from the South Side”). Families are greatly influenced by the communities in which they reside. Nurses must understand the culture of the community in which they work or to which the patient will return (Table 15-2). Assessment of the community is particularly important in creating discharge plans for families from various cultures. Their lives may be broadened or restricted depending on the facilities within the community. A few factors to consider are housing, access to public transportation, city services, safety, and health care delivery systems. The nurse has immediate access to the patient and therefore becomes an important liaison between various agencies that address specific needs.

Table 15-2

Cultural Influences on the Family

| CULTURAL GROUP | FAMILY AND KINSHIP STRUCTURE | COMMUNICATION | HEALTH BELIEFS AND PRACTICES | FAMILY AND CHILD CARE PRACTICES |

| Hispanic | ||||

| Mexican American | ||||

| Puerto Rican | Extended and patriarchal family. | Bilingual—Spanish and English. | Avoid iron supplements because they are considered “hot” medications. Classify foods and medications as hot, cold, and cool. Classify foods as hot and cold. | |

| Cuban | Bilingual—Spanish and English. | |||

| Haitian | ||||

| Rely on native language. | ||||

| African American | ||||

| English | ||||

| Asian | ||||

| Vietnamese | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||

Years

Years