Violeta A. Berbiglia and Barbara Banfield

Self-care deficit theory of nursing

“Nursing is practical endeavor, but it is practical endeavor engaged in by persons who have specialized theoretic nursing knowledge with developed capabilities to put this knowledge to work in concrete situations of nursing practice”

(Orem, 2001, p. 161).

Dorothea E. Orem

1914 to 2007

Credentials and background of the theorist

Dorothea Elizabeth Orem, one of America’s foremost nursing theorists, was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1914. She began her nursing career at Providence Hospital School of Nursing in Washington, DC, where she received a diploma of nursing in the early 1930s. Orem received a BS in Nursing Education from Catholic University of America (CUA) in 1939, and she received an MS in Nursing Education from the same university in 1946.

Photo credit: Gerd Bekel Archives, Cloppenburg, Germany.

Previous authors: Susan G. Taylor, Angela Compton, Jeanne Donohue Eben, Sarah Emerson, Nergess N. Gashti, Ann Marriner Tomey, Margaret J. Nation, and Sherry B. Nordmeyer. Sang-arun Isaramalai is acknowledged for research and editorial assistance in a previous edition.

Orem’s early nursing experiences included operating room nursing, private duty nursing (home and hospital), hospital staff nursing on pediatric and adult medical and surgical units, evening supervisor in the emergency room, and biological science teaching. Orem held the directorship of both the nursing school and the Department of Nursing at Providence Hospital, Detroit, from 1940 to 1949. After leaving Detroit, she spent 8 years (1949 to 1957) in Indiana working at the Division of Hospital and Institutional Services of the Indiana State Board of Health. Her goal was to upgrade the quality of nursing in general hospitals throughout the state. During this time, Orem developed her definition of nursing practice (Orem, 1956).

In 1957, Orem moved to Washington, DC, to take a position at the Office of Education, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, as a curriculum consultant. From 1958 to 1960, she worked on a project to upgrade practical nurse training. That project stimulated a need to address the question: What is the subject matter of nursing? As a result, Guides for Developing Curricula for the Education of Practical Nurses was developed (Orem, 1959). Later that year, Orem became an assistant professor of nursing education at CUA. She subsequently served as acting dean of the School of Nursing and as associate professor of nursing education. She continued to develop her concepts of nursing and self-care at CUA. Formalization of concepts sometimes was accomplished alone and sometimes with others. Members of the Nursing Models Committee at CUA and the Improvement in Nursing Group, which later became the Nursing Development Conference Group (NDCG), all contributed to the development of the theory. Orem provided intellectual leadership throughout these collaborative endeavors.

In 1970, Orem left CUA and began her own consulting firm. Orem’s first published book was Nursing: Concepts of Practice (Orem, 1971). She was editor for the NDCG as they prepared and later revised Concept Formalization in Nursing: Process and Product (NDCG, 1973, 1979). In 2004, a reprint of the second edition was produced and distributed by the International Orem Society for Nursing Science and Scholarship (IOS). Subsequent editions of Nursing: Concepts of Practice were published in 1980, 1985, 1991, 1995, and 2001. Orem retired in 1984 and continued working, alone and with colleagues, on the development of the Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory (SCDNT).

Georgetown University conferred on Orem the honorary degree of Doctor of Science in 1976. She received the CUA Alumni Association Award for Nursing Theory in 1980. Other honors received included Honorary Doctor of Science, Incarnate Word College, 1980; Doctor of Humane Letters, Illinois Wesleyan University, 1988; Linda Richards Award, National League for Nursing, 1991; and Honorary Fellow of the American Academy of Nursing, 1992. She was awarded the Doctor of Nursing Honoris Causae from the University of Missouri in 1998.

At age 92, Dorothea Orem’s life ended after a period of being bedridden. She died Friday, June 22, 2007, at her residence on Skidaway Island, Georgia. Survivors were her lifelong friend, Walene Shields of Savannah, and her cousin Martin Conover of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Tributes by Orem’s close colleagues were featured in the IOS official journal, Self-Care, Dependent-Care & Nursing (SCDCN).

Orem’s many papers and presentations provide insight into her views on nursing practice, nursing education, and nursing science. Some of these papers are now available to nursing scholars in a compilation edited by Renpenning and Taylor (2003). Other papers of Orem and scholars who worked with her in the development of the theory can be found in the Orem Archives at The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Theoretical sources

Orem (2001) stated, “Nursing belongs to the family of health services that are organized to provide direct care to persons who have legitimate needs for different forms of direct care because of their health states or the nature of their health care requirements” (p. 3). Like other direct health services, nursing has social features and interpersonal features that characterize the helping relations between those who need care and those who provide the required care. What distinguishes these health services from one another is the helping service that each provides. Orem’s SCDNT provides a conceptualization of the distinct helping service that nursing provides.

Early on, Orem recognized that if nursing was to advance as a field of knowledge and as a field of practice, a structured, organized body of nursing knowledge was needed. From the mid-1950s, when she first put forth a definition of nursing, until shortly before her death in 2007, Orem pursued the development of a theoretical structure that would serve as an organizing framework for such a body of knowledge.

The primary source for Orem’s ideas about nursing was her experiences in nursing. Through reflection on nursing practice situations, she was able to identify the proper object, or focus, of nursing. The question that directed Orem’s (2001) thinking was, “What condition exists in a person when judgments are made that a nurse(s) should be brought into the situation?” (p. 20). The condition that indicates the need for nursing assistance is “the inability of persons to provide continuously for themselves the amount and quality of required self-care because of situations of personal health” (Orem, 2001, p. 20). It is the proper object or focus that determines the domain and boundaries of nursing, both as a field of knowledge and as a field of practice. The specification of the proper object of nursing marks the beginning of Orem’s theoretical work. The efforts of Orem, working independently as well as with colleagues, resulted in the development and refinement of the SCDNT. Consisting of a number of conceptual elements and theories that specify the relationships among these concepts, the SCDNT is a general theory, “one that is descriptively explanatory of nursing in all types of practice situations” (Orem, 2001, p. 22). Originally, three specific theories were articulated, the theory of nursing systems, the theory of self-care deficits, and the theory of self-care. An additional theory, the theory of dependent care, has been articulated. This theory is regarded as being parallel with the theory of self-care and serves to illustrate the ongoing development of the SCDNT.

In addition to her experiences in nursing practice situations, Orem was well versed in contemporary nursing literature and thought. Her association with nurses over the years provided many learning experiences, and she viewed her work with graduate students and her collaborative work with colleagues as valuable endeavors. Orem cited many other nurses’ works in terms of their contributions to nursing, including, but not limited to, Abdellah, Henderson, Johnson, King, Levine, Nightingale, Orlando, Peplau, Riehl, Rogers, Roy, Travelbee, and Wiedenbach.

Orem’s familiarity with literature was not limited to nursing literature. In her discussion of various topics related to nursing, Orem cited authors from a number of other disciplines. The influence of scholars such as Allport (1955), Arnold (1960a, 1960b), Barnard (1962), Fromm (1962), Harre (1970), Macmurray (1957, 1961), Maritain (1959), Parsons (1949, 1951), Plattel (1965), and Wallace (1979, 1996) can be seen in Orem’s ideas and positions. Familiarity with these sources helps to promote a comprehensive understanding of Orem’s work.

Foundational to Orem’s SCDNT is the philosophical system of moderate realism. Banfield (1998, 2008, 2011) conducted philosophical inquiries to explicate the metaphysical and epistemological underpinnings of Orem’s work. These inquiries revealed consistency between Orem’s views regarding the nature of reality, human beings, the environment and nursing as a science; ideas and positions associated with the philosophy of moderate realism. Taylor, Geden, Isaramalai, and Wongvatunyu (2000) have also explored the philosophical foundations of the SCDNT.

According to the moderate realist position, there is a world that exists independent of the thoughts of the knower. Although the nature of the world is not determined by the thoughts of the knower, it is possible to obtain knowledge about the world.

Orem did not specifically address the nature of reality; however, statements and phrases that she uses reflect a moderate realist position. Four categories of postulated entities are identified as establishing the ontology of the SCDNT (Orem, 2001, p. 141). These four categories are (1) persons in space-time localizations, (2) attributes or properties of these persons, (3) motion or change, and (4) products brought into being.

With regard to the nature of human beings, “the view of human beings as dynamic, unitary beings who exist in their environments, who are in the process of becoming, and who possess free-will as well as other essential human qualities” is foundational to the SCDNT (Banfield, 1998, p. 204). This position, which reflects the philosophy of moderate realism, can be seen throughout Orem’s work.

Orem (1997) identified “five broad views of human beings that are necessary for developing understanding of the conceptual constructs of the SCDNT and for understanding the interpersonal and societal aspects of nursing systems” (p. 28). These are the view of person, agent, user of symbols, organism,and object. The view of human beings as person reflects the philosophical position of moderate realism; it is this position regarding the nature of human beings that is foundational to Orem’s work. She made the point that taking a particular view for some practical purpose does not negate the position that human beings are unitary beings (Orem, 1997, p. 31).

The view of person-as-agent is central to the SCDNT. Self-care, which refers to those actions in which a person engages for the purpose of promoting and maintaining life, health, and well-being, is conceptualized as a form of deliberate action. “Deliberate action refers to actions performed by individual human beings who have intentions and are conscious of their intentions to bring about, through their actions, conditions or states of affairs that do not at present exist” (Orem, 2001, pp. 62–63). When engaging in deliberate action, the person acts as an agent. The view of person-as-agent is also reflected in the SCDNT’s conceptual elements of the nursing care and dependent care. In relation to the view of person-as-agent and the idea of deliberate action, Orem cited a number of scholars, including Arnold, Parsons, and Wallace. She identified seven assumptions regarding human beings that pertain to deliberate action (Orem, 2001, p. 65). These explicit assumptions, while addressing deliberate action, rest upon the implicit assumption that human beings have free will.

The SCDNT represents Orem’s work regarding the substance of nursing as a field of knowledge and as a field of practice. She also put forth a position regarding the form of nursing as a science, identifying it as a practical science. In relation to her ideas about the form of nursing science, Orem cites the work of Maritain (1959) and Wallace (1979), philosophers who were associated with the moderate realist tradition, . In practical sciences, knowledge is developed for the sake of the work to be done. In the case of nursing, knowledge is developed for the sake of nursing practice. Two components make up the practical science: the speculative and the practical. The speculatively practical component is theoretical in nature, while the practically practical component is directive of action. The SCDNT represents speculatively practical knowledge. Practically practical nursing science is made up of models of practice, standards of practice, and technologies.

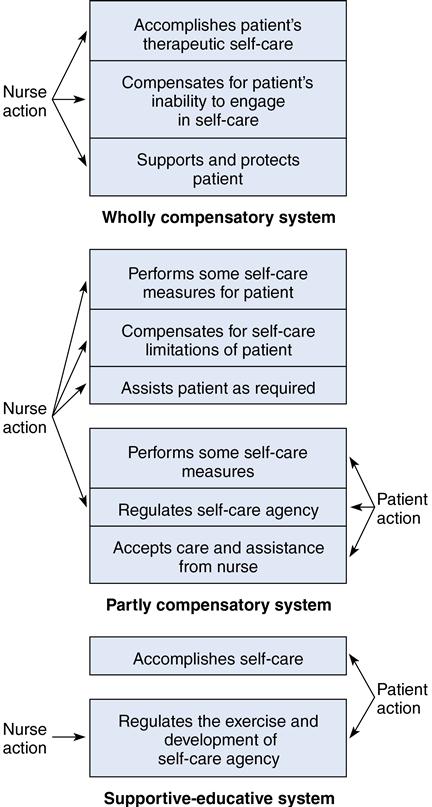

Orem (2001) identified two sets of speculatively practical nursing science: nursing practice sciences and foundational nursing sciences. The set of nursing practice sciences includes (1) wholly compensatory nursing science, (2) partly compensatory nursing science, and (3) supportive developmental nursing science. The foundational nursing sciences are (1) the science of self-care, (2) the science of the development and exercise of the self-care agency in the absence or presence of limitations for deliberate action, and (3) the science of human assistance for persons with health-associated self-care deficits. In relation to this proposed structure of nursing sciences, Orem stated, “the isolation, naming, and description of the two sets of sciences are based on my understanding of the nature of the practical sciences, on my knowledge of the organization of subject matter in other practice fields, and on my understanding of components of curricula for education for the professions” (pp. 174–175).

In addition to the two components or types of practical science, scientific knowledge necessary for nursing practice includes sets of applied sciences and basic non-nursing sciences. In the development of applied sciences, theories from other fields are used to solve problems in the practice field. These applied nursing sciences have yet to be identified and developed. Box 14–1 depicts the structure of nursing science.

Orem’s articulation of the form of nursing science provided the framework for the development of a body of knowledge for the education of nurses and for the provision of nursing care in concrete situations of nursing practice. The SCDNT with its conceptual elements and four theories identifies the substance or content of nursing science.