The Term Newborn

Objectives

1. Define each key term listed.

3. Demonstrate the steps in the physical assessment of the newborn.

4. State four methods of maintaining the body temperature of a newborn.

5. State the cause and describe the appearance of physiological jaundice in the newborn.

7. State the methods of preventing infection in newborns.

8. Interpret discharge teaching for the mother and her newborn.

Key Terms

acrocyanosis (ăk-rō-sī-ă-NŌ-sĭs, p. 292)

caput succedaneum (KĂP-ŭt sŭk-sĕ-DĀ-nē-ŭm, p. 281)

cephalhematoma (sĕf-ă-lō-hē-mă-TŌ-mă, p. 281)

circumcision (sŭr-kŭm-SĬZH-ŭn, p. 290)

dancing reflex (p. 280)

Epstein’s pearls (p. 292)

fontanelles (fŏn-tă-NĔLZ, p. 281)

head lag (p. 280)

icterus neonatorum (ĬK-tŭr-ŭs nē-ō-nā-TŎR-ŭm, p. 293)

lanugo (lă-NŪ-gō, p. 292)

meconium (mĕ-KŌ-nē-ŭm, p. 297)

milia (MĬL-ē-ă, p. 292)

molding (p. 280)

mongolian spots (p. 292)

Moro reflex (p. 280)

rooting reflex (p. 280)

scarf sign (p. 290)

tissue turgor (p. 292)

tonic neck reflex (p. 280)

vernix caseosa (VŬR-nĭks kā-sē-Ō-să, p. 292)

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer

The arrival of the newborn, or neonate, begins a highly vulnerable period during which many psychological and physiological adjustments to life outside the uterus must be made. The fetus that remains in the uterus until maturity has reached a major goal. The infant’s genetic background, the health of the recent uterine environment, a safe delivery, and the care during the first month of life further contribute to this adjustment.

The infant mortality rate is the ratio of the number of deaths of infants younger than age 1 year during any given year to the number of live births occurring in the same year. The rate is usually expressed as the number of deaths per 1000 live births. The infant death rate is highest in the first month and is referred to as the neonatal mortality rate. The first 24 hours of life are the most dangerous. The infant mortality rate is considered to be one of the best means of determining the health of a country. To obtain accurate figures, all births and deaths must be registered. In the United States this registration is required by law. Each birth certificate is permanently filed with the state bureau of vital statistics.

Morbidity (morbidus, “sick”) refers to the state of being diseased or sick. Morbidity rates show the incidence of disease in a specific population during a certain time frame. Perinatology is the study and support of the fetus and neonate. The term perinatal mortality designates fetal and neonatal deaths related to prenatal conditions and delivery circumstances. See Chapter 1 for details concerning statistics in the United States.

Low-birth-weight newborns and limited access to health care are major causes of infant morbidity. Reducing infant morbidity rates can reduce the resulting incidence of disability, which can have an impact on the growth and development of children. The nurse can play a vital role in educating new parents about health care and the developmental needs of their newborn.

Adjustment to Extrauterine Life

When a child is born, an orderly, continuous adaptation from fetal life to extrauterine life takes place. All the body systems undergo some change. Respirations are stimulated by chilling and by chemical changes within the blood. Sensory and physical stimuli also appear to play a role in respiratory function. The first breath opens the alveoli. The infant then enters the world of air exchange, at which time an independent existence begins. This process also initiates cardiopulmonary interdependence. The newborn’s ability to metabolize food is hampered by the immaturity of the digestive system, particularly deficiencies in enzymes from the pancreas and liver. The kidneys are structurally developed, but their ability to concentrate urine and maintain fluid balance is limited because of a decreased rate of glomerular flow and limited renal tubular reabsorption. Most neurological functions are primitive (see the discussion of the individual body systems in this chapter).

Phase 3: Care of the Newborn

Phase 3 care of the newborn covers the physical characteristics and nursing assessment of the normal term newborn, by body system. Refer to Chapter 6 for care of the newborn immediately after birth (Phase 1) and Chapter 9 for care of the newborn on admission to the nursery or postpartum unit (Phase 2).

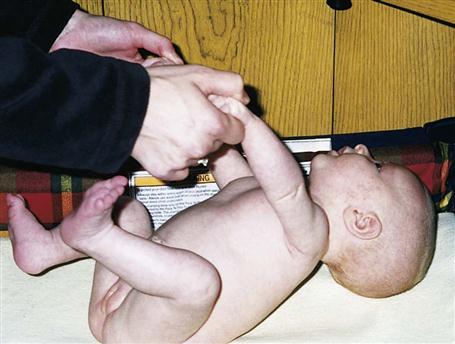

Nervous System: Reflexes

The nervous system directs most of the body’s activity. Newborns can move their arms and legs vigorously but cannot control them. When the infant is lifted from the bed, the head will fall back because the newborn cannot maintain neutral position of the head. This is called a head lag (Figure 12-1). The reflexes full-term infants are born with, such as blinking, sneezing, gagging, sucking, and grasping (Figure 12-2), help to keep them alive. They can cry, swallow, and lift their heads slightly when lying on their abdomen.

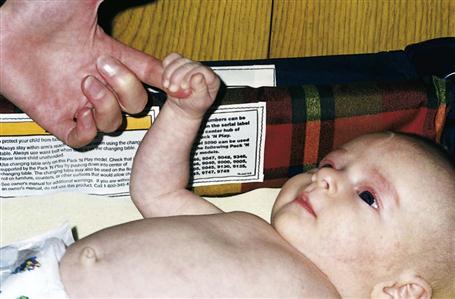

If the crib is jarred, infants draw their legs up and the arms fan out and then come toward midline in an embrace position. This is normal and is called the Moro reflex (Figure 12-3). Its absence may indicate abnormalities of the nervous system. The rooting reflex causes the infant’s head to turn in the direction of anything that touches the cheek, in anticipation of food. The nurse uses this when helping a mother to breastfeed her infant. A breast touching the cheek causes the infant to turn toward it to find the nipple (see Chapter 9).

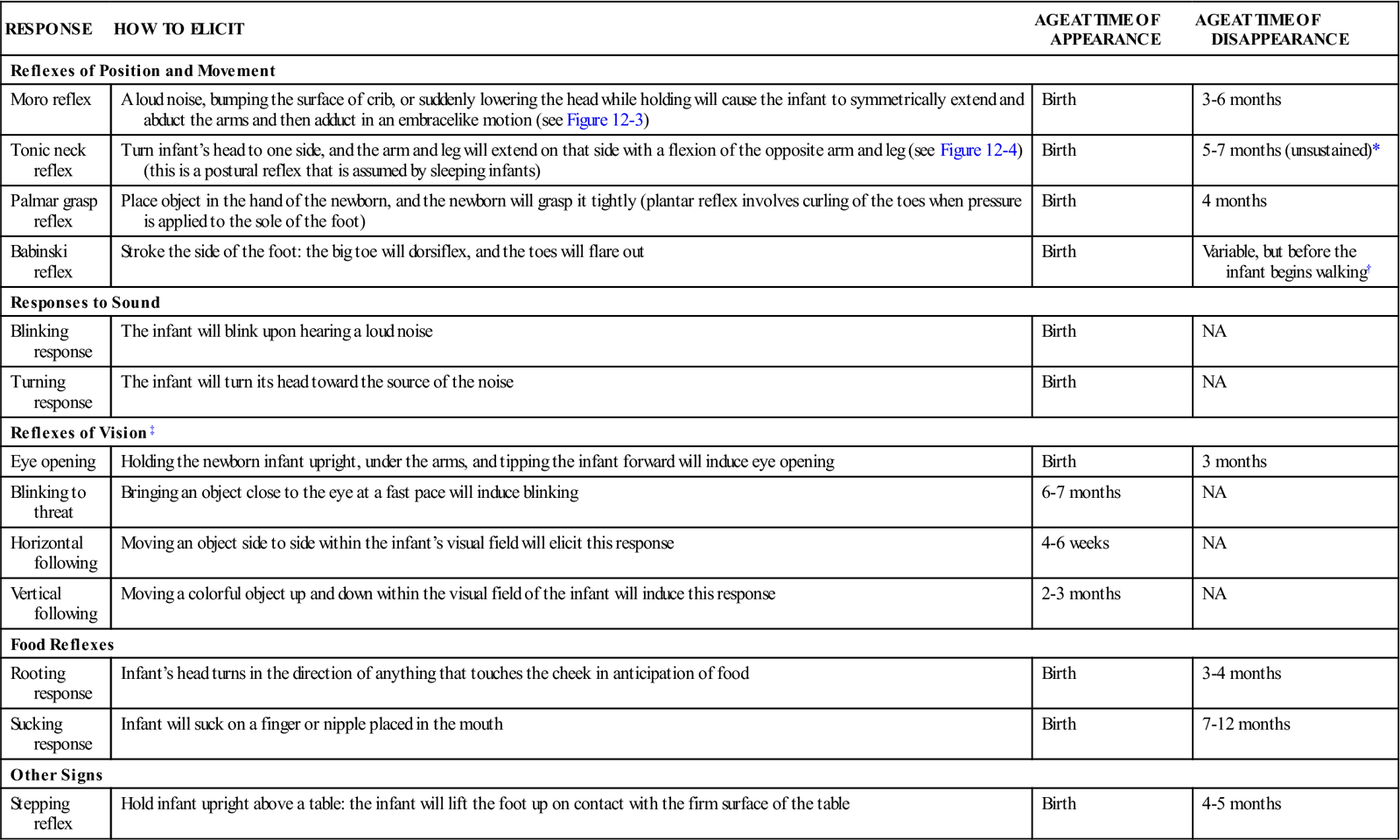

The tonic neck reflex is a postural reflex that is sometimes assumed by sleeping infants. The head is turned to one side, the arm and leg are extended on the same side, and the opposite arm and leg are flexed in a “fencing” position. This reflex disappears by the seventh month of life (Figure 12-4). Prancing movements of the legs, seen when an infant is held upright on the examining table, are termed the dancing reflex. Table 12-1 lists ages at which the neurological signs of infancy appear and disappear.

Table 12-1

Ages of Appearance and Disappearance of Neurological Signs Unique to Infancy

| RESPONSE | HOW TO ELICIT | AGE AT TIME OF APPEARANCE | AGE AT TIME OF DISAPPEARANCE |

| Reflexes of Position and Movement | |||

| Moro reflex | A loud noise, bumping the surface of crib, or suddenly lowering the head while holding will cause the infant to symmetrically extend and abduct the arms and then adduct in an embracelike motion (see Figure 12-3) | Birth | 3-6 months |

| Tonic neck reflex | Turn infant’s head to one side, and the arm and leg will extend on that side with a flexion of the opposite arm and leg (see Figure 12-4) (this is a postural reflex that is assumed by sleeping infants) | Birth | 5-7 months (unsustained)* |

| Palmar grasp reflex | Place object in the hand of the newborn, and the newborn will grasp it tightly (plantar reflex involves curling of the toes when pressure is applied to the sole of the foot) | Birth | 4 months |

| Babinski reflex | Stroke the side of the foot: the big toe will dorsiflex, and the toes will flare out | Birth | Variable, but before the infant begins walking† |

| Responses to Sound | |||

| Blinking response | The infant will blink upon hearing a loud noise | Birth | NA |

| Turning response | The infant will turn its head toward the source of the noise | Birth | NA |

| Reflexes of Vision‡ | |||

| Eye opening | Holding the newborn infant upright, under the arms, and tipping the infant forward will induce eye opening | Birth | 3 months |

| Blinking to threat | Bringing an object close to the eye at a fast pace will induce blinking | 6-7 months | NA |

| Horizontal following | Moving an object side to side within the infant’s visual field will elicit this response | 4-6 weeks | NA |

| Vertical following | Moving a colorful object up and down within the visual field of the infant will induce this response | 2-3 months | NA |

| Food Reflexes | |||

| Rooting response | Infant’s head turns in the direction of anything that touches the cheek in anticipation of food | Birth | 3-4 months |

| Sucking response | Infant will suck on a finger or nipple placed in the mouth | Birth | 7-12 months |

| Other Signs | |||

| Stepping reflex | Hold infant upright above a table: the infant will lift the foot up on contact with the firm surface of the table | Birth | 4-5 months |

NA, Not applicable.

NOTE: Absence of these reflexes or prolonged appearance may indicate a neurological problem and requires further follow-up.

*Arm and leg posturing can be broken by infant after a few minutes, despite continued neck stimulus.

†Usually of no diagnostic significance until after age 2 years.

‡Holding the newborn infant upright under the arms will induce eye opening.

Head

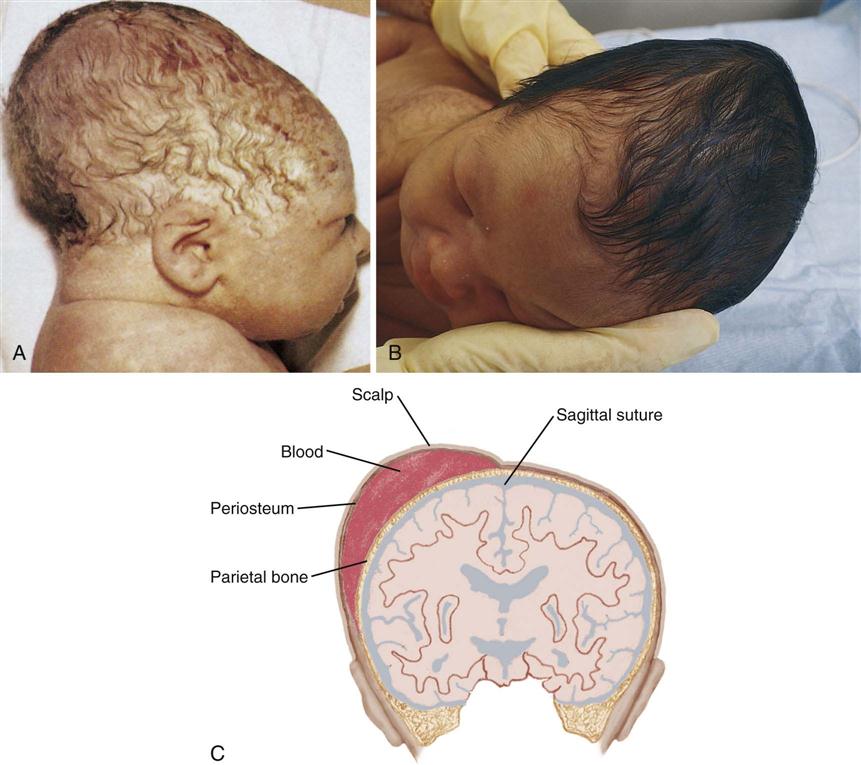

The brain grows rapidly before birth, and therefore the newborn’s head is large in comparison with the rest of the body. The normal limits of head circumference range from 32 to 36 cm (12.5 to 14.1 inches) (Skill 12-1). The head may be out of shape from molding (the conforming of the fetal head to the size and shape of the birth canal) (Figure 12-5, A). There may also be swelling of the soft tissues of the scalp, which is termed caput succedaneum. It gradually subsides without treatment. Occasionally, a cephalhematoma (cephal, “head,” hemato, “blood,” toma, “tumor”) protrudes from beneath the scalp (see Figure 12-5, B and C). This condition is caused by a collection of blood beneath the periosteum of the cranial bone. It may be seen on one or both sides of the head but does not cross the suture line. This condition usually recedes within a few weeks without treatment.

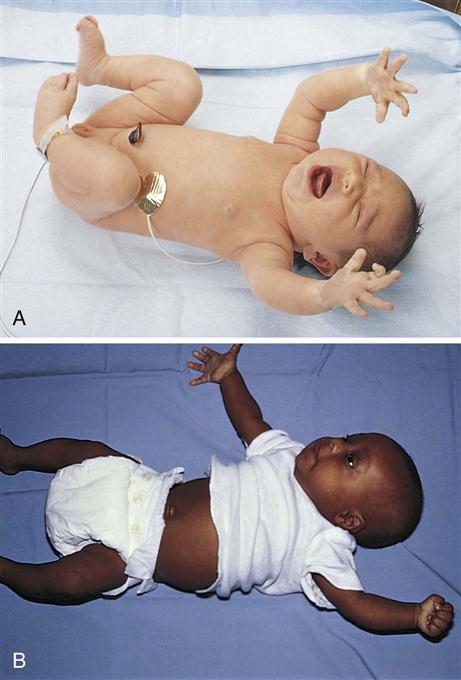

The fontanelles are unossified spaces or soft spots on the cranium of a young infant. They protect the head during delivery by permitting the process of molding and allow for further brain growth during the next  years. The anterior fontanelle is diamond shaped and is located at the junction of the two parietal and two frontal bones. It usually closes by age 12 to 18 months. The posterior fontanelle is triangular and is located between the occipital and parietal bones. It is smaller than the anterior fontanelle and is usually ossified by the end of the second month. These areas are covered by a tough membrane, and there is little chance of their being injured during ordinary care. The features of the newborn’s face are small. The mouth and lips are well developed because they are necessary to obtain food. The newborn can both taste and smell. In fact, the newborn can recognize the scent of the mother’s milk on the breast pad.

years. The anterior fontanelle is diamond shaped and is located at the junction of the two parietal and two frontal bones. It usually closes by age 12 to 18 months. The posterior fontanelle is triangular and is located between the occipital and parietal bones. It is smaller than the anterior fontanelle and is usually ossified by the end of the second month. These areas are covered by a tough membrane, and there is little chance of their being injured during ordinary care. The features of the newborn’s face are small. The mouth and lips are well developed because they are necessary to obtain food. The newborn can both taste and smell. In fact, the newborn can recognize the scent of the mother’s milk on the breast pad.

Eyes

The healthy newborn can see and can fixate on points of contrast. The newborn shows a preference for observing a human face and follows moving objects. Visual stimulation is thus an important ingredient in newborn care. Toys that make sounds and have contrasting colors attract the newborn.

Most newborns appear cross-eyed because their eye muscle coordination is not fully developed. At first, the eyes appear to be blue or gray; the permanent coloring becomes fixed between ages 6 and 12 months. The eyelids are closed most of the time. Tears do not appear until approximately age 1 to 3 months because of the immaturity of the lacrimal gland ducts.

Ears

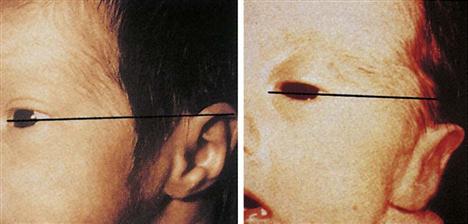

The ears are well developed but small at birth. The ears are assessed for placement because low-set ears may indicate a congenital abnormality in another part of the body. An imaginary line drawn from the outer canthus of the eye should be even with the upper tip of the pinna of the ear (Figure 12-6). The hearing ability of the newborn is well developed at birth, but the sick or premature newborn may not respond to sounds that are heard. The presence of amniotic fluid in the ear canal can diminish hearing, but normal drainage and sneezing that occur shortly after birth help clear the ear canal.

The newborn will react to sudden sound with an increase in pulse rate and respirations or a display of the startle reflex. Increased responses to vocal stimulation, particularly higher-pitched female voices, have been documented. The ability to discriminate between the mother’s voice and the voices of others may occur as early as age 3 days. Hearing is important to the development of normal speech. The nurse observes and records how the newborn reacts to sound, such as a rattle or the voice of the caretaker. The infant will respond to voices by decreasing motor activity and sucking activity and turning the head toward the sound.

One type of test used to measure infant hearing is the ALGO hearing screening test, which analyzes hearing by sending a series of soft clicks into the sleeping infant’s ear (Figure 12-7). The infant’s brain responds with a specific brain wave that is referred to as an auditory brainstem response (ABR). The response is compared by computer to normal responses, and a pass/fail score is recorded. Another type of test is the otoacoustic emissions test (OAE) that measures sounds from the cochlea in response to sound stimulation. Newborn hearing screening programs have become part of the protocol of care in hospital nurseries across the United States.

The ears and nose need no special attention except for cleansing with a soft cloth during the bath. Occasionally they may be externally cleansed with a cotton ball moistened slightly with water. The bony canal of the external ear is not well developed, and the tympanic membrane is vulnerable to injury. The nurse should not insert applicators. They may cause serious injury to the tympanic membrane if inserted too far into the ear canal or if the infant moves suddenly.

Sensory Overload.

Sensory overload can occur if there is too much stimulation. This detrimental overload can occur in the hospital environment, where lights are bright and voices carry. The nurse can help to modify this situation by responding quickly to alarms and by speaking quietly when working near the infant.

Sleep

The neonate sleeps approximately 15 to 20 hours a day. There is a gradual change in the quantity and quality of sleep as the newborn matures. At birth the newborn passes through the phases of sleep-wake states as part of the adjustment to life outside of the uterus:

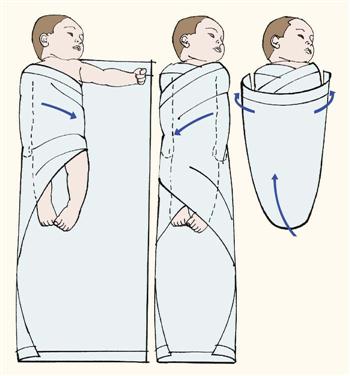

The environment plays a large role in the infant’s sleep behavior. The nurse can help the parent to understand that normal conversational tones can quiet a newborn, whereas high noise levels can cause increased crying. Wrapping an infant snugly can maintain temperature and promote sleep, as can gentle horizontal rocking. An infant held upright on the shoulder and rocked in a vertical fashion is likely to maintain an alert state. Newborns exhibit a specific pattern of reactivity that can influence the response to stimuli and bonding, as follows:

• Quiet sleep: Infant sleeps and does not move.

• Active alert: The infant displays diffuse motor activity.

• Crying: The infant’s cry is accompanied by vigorous motor activity of extremities.

Pain

In the past it was believed that newborns did not experience pain because of immaturity of the nerve pathways to the brain. It is now thought that fibers that conduct pain stimuli to the spinal cord are in place early in fetal life. These are called nociceptors (noci, “pain,” ceptus, “to receive”). The newborn also produces catecholamines and cortisol in response to stress. Heart rate and respiratory rates change. Blood pressure increases, and blood glucose levels rise. Newborns should be medicated for pain when discomfort is anticipated.

The nurse is responsible for understanding the physiological and behavioral responses to pain and providing appropriate pain relief measures. Untreated pain in early infancy can have long-term effects because the pain pathways and structures required for long-term memory are well developed by 24 weeks of gestation. Unrelieved pain can also cause exhaustion and irritability and slow the healing process. Some infants may be too weak to demonstrate a visible response to pain, and so behavioral responses and physiological changes must both be monitored. There are several pain assessment tools available for preterm and term infants. Pain assessment tools appropriate for the older child are discussed in Chapter 21. Examples of pain assessment tools for infants include the following:

The pain assessment findings should be documented and appropriate nursing interventions implemented.

Adequate pain relief in newborns who undergo painful procedures (e.g., circumcision) can reduce postoperative morbidity. Evaluation of pain in the neonate can be based on changes in vital signs and behavior of the infant and decreased oxygen saturation rates (Figure 12-8). Swaddling with the hand near the mouth, cuddling, rocking, nonnutritive sucking, and a quiet environment are noninvasive methods of pain relief for newborn infants. Oral sucrose is an effective pain reliever for minor procedures (Harrison et al., 2010). Morphine, fentanyl, and topical anesthetics can be used safely for severe pain. The nurse must be aware of safe dosage ranges and must observe infants closely for side effects or signs of withdrawal when the medication is gradually decreased and then discontinued.

Conditioned Responses

A conditioned response or reflex is one that is learned over time. It is an unconscious response to an external stimulus. An example is the hungry infant who stops crying merely at the sound of the caregiver’s footsteps, even though food is not yet available. Emotions are particularly subject to this type of conditioning. As an infant matures, the mere sight of an object that once caused pain can precipitate fear.

Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale

The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale, developed by T. B. Brazelton (1973), has increased the understanding of the newborn’s capabilities. Among other areas of assessment, this scale measures the inherent neurological capacities of the newborn and responses to selected stimuli. Areas tested include alertness, response to visual and auditory stimuli, motor coordination, level of excitement, and organizational process in response to stress.

Respiratory System

The unborn fetus is completely dependent on the mother for all vital functions. The fetus needs oxygen and nourishment to grow. These nutrients are supplied through the bloodstream of the pregnant woman by way of the placenta and the umbilical cord. The fetus is relieved of the waste products of metabolism by the same route. The lungs are not inflated and are almost completely inactive. The circulatory system is adapted only to life within the uterus. Little blood flows through the pulmonary artery because of natural openings within the heart and vessels that close at birth or shortly thereafter.

When the umbilical cord is clamped and cut, the lungs take on the function of breathing oxygen and removing carbon dioxide. The first breath helps to expand the collapsed lungs, although full expansion does not occur for several days. The health care provider assists the first respiration by removing mucus from the passages to the lungs. The infant’s cry should be strong and healthy. The most critical period for the newborn is the first hour of life, when the drastic change from life within the uterus to life outside the uterus takes place.

Mucus may be seen draining from the nose or mouth, and it is wiped away with a sterile gauze square. Gently clearing mucus with a bulb syringe may also be indicated (Skill 12-2). When this procedure is done orally, the tip is inserted into the side of the mouth to avoid stimulating the gag reflex. Parents are taught how to use the bulb syringe and are instructed to keep one next to the newborn during the early weeks of life.

The nurse can assist newborns to maintain a patent airway by positioning them on their back or side and dressing them in clothing that maintains warmth while allowing expansion of the lungs. The nurse should record vital signs and suction mucus as needed, first from the mouth and throat and then from the nose.

Apgar Score

The Apgar score is a standardized method of evaluating the newborn’s condition immediately after delivery. Five objective signs are measured: heart rate, respiration, muscle tone, reflexes, and color. The score is obtained 1 minute after birth and again after 5 minutes (see Table 6-7 in Chapter 6). On admission of the newborn to the nursery, the Apgar score is reviewed to determine any particular difficulties encountered during the birth process. The health care provider’s orders are noted. The nurse must observe the newborn very closely. Respiratory distress may be evidenced by the rate and character of respirations, color (cyanosis), and general behavior (see Chapter 13). Sternal retractions are reported immediately.

Circulatory System

The mother’s blood carried essential oxygen to the placenta, which sent it to each cell of the fetus while in the uterus. The health care provider cuts off this supply by severing the umbilical cord. Thereafter the newborn depends on his or her own systemic circulation and pulmonary circulation (see Figure 3-7).

The newborn has approximately 300 mL of circulatory blood volume. The circulation of blood in the fetus differs from that in the newborn in that most fetal blood bypasses the lungs (see Chapter 3). Some of the blood goes from the right atrium to the left atrium of the heart through an opening (the foramen ovale) in the septum. Some passes from the pulmonary artery to the thoracic aorta by way of the ductus arteriosus. These normal openings close soon after birth. If they fail to close, the infant may be cyanotic because part of the blood continues to bypass the lungs and does not pick up oxygen.

Murmurs are caused by blood leaking through openings that have not yet closed. Murmurs may be functional (innocent) or organic (caused by improper heart formation). Functional murmurs result from the sound of blood passing through normal valves. Organic murmurs are caused by blood passing through abnormal openings. The majority of heart murmurs are not serious, but they should be checked periodically to rule out other pathological conditions.

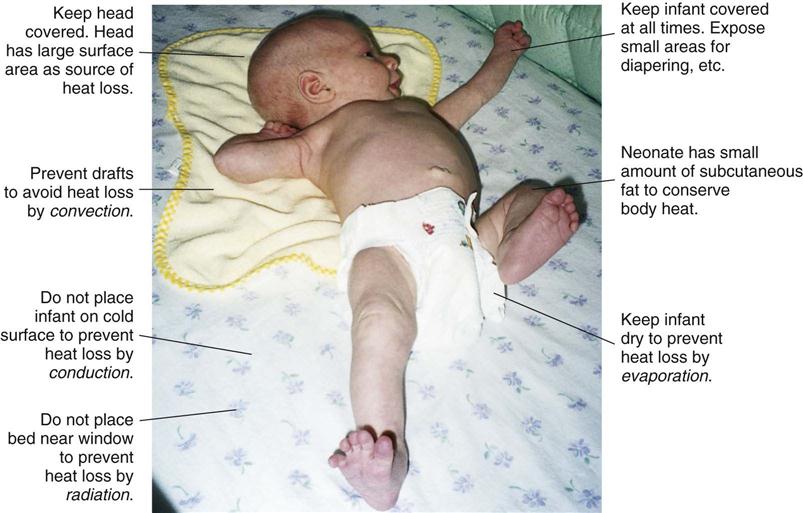

Providing Warmth

The newborn has an unstable heat-regulating system. Body temperature falls immediately after birth to about 35.5° C (96.0° F). Within a few hours, it climbs slowly to a range of 36.6° C to 37.2° C (97.8° F to 98.9° F). The body temperature is influenced by that of the room and by the number of blankets covering the infant. The temperature of the nursery, or of the mother’s room in the case of rooming-in, is kept at 21° C to 24° C (69° F to 75° F). The humidity should be between 45% and 55%. The air in the room must be fresh, but there should be no drafts.

The newborn’s hands and feet are not used as a guide to determine warmth because the infant’s extremities are cooler than the rest of the body. Acrocyanosis (acro, “extremity,” cyanosis, “blue color”) is also evident because of sluggish peripheral circulation. The newborn cannot adapt to changes in temperature. The nurse wraps the infant in a blanket whenever the infant leaves the nursery (Skill 12-3). The infant’s heat perception is poor, so the nurse must be careful when applying any form of external heat.

Because the sweat glands do not function effectively during the neonatal period, the newborn infant is at risk for developing an elevated temperature if overdressed or if placed in an overheated environment. A red skin rash may develop in response to overheating. Maintaining body temperature in the newborn is summarized in Figure 12-9. See also Table 9-2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree