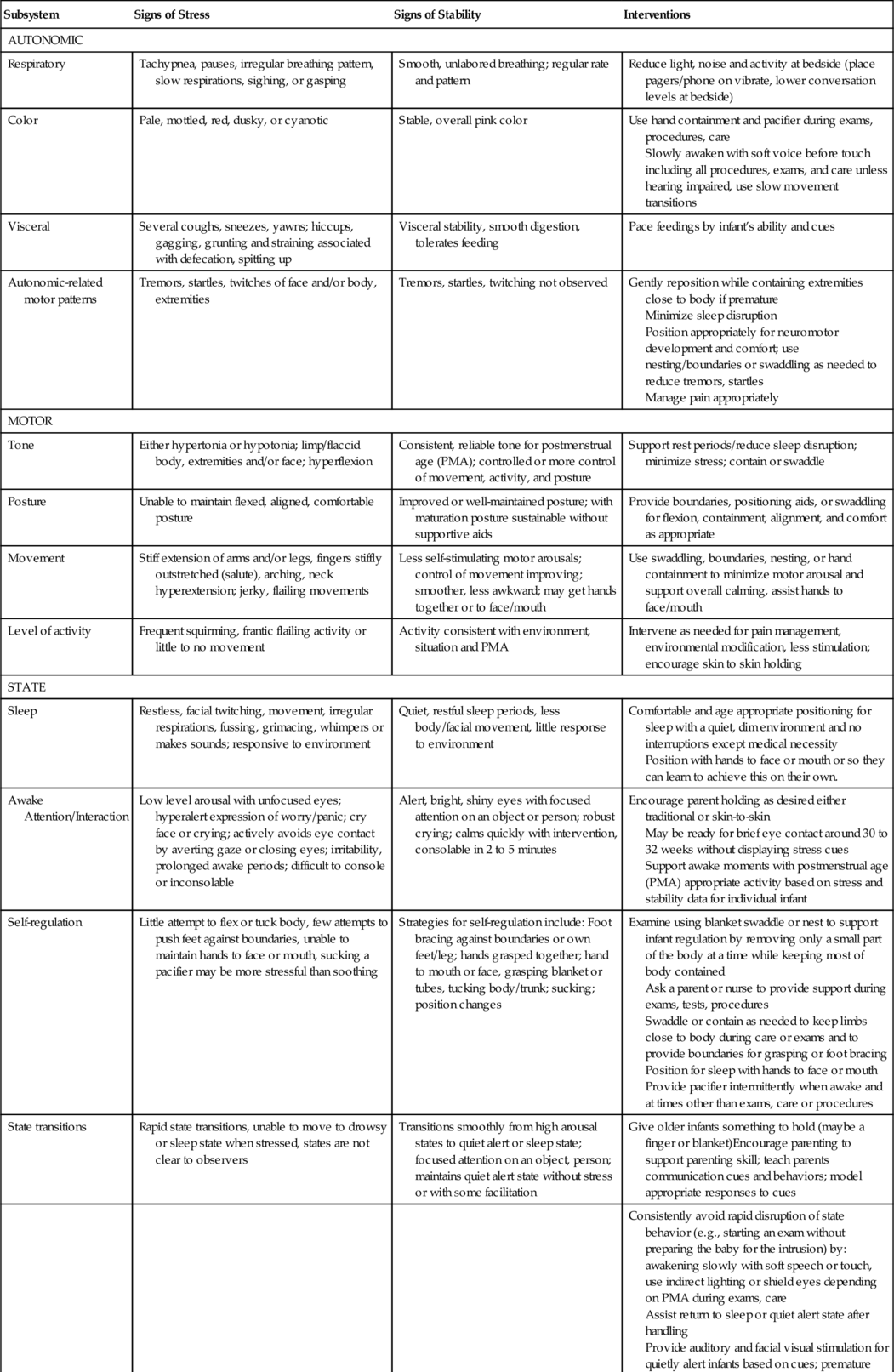

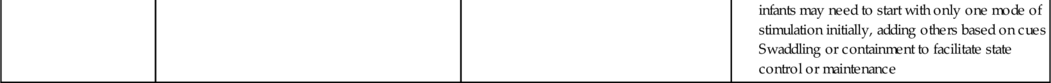

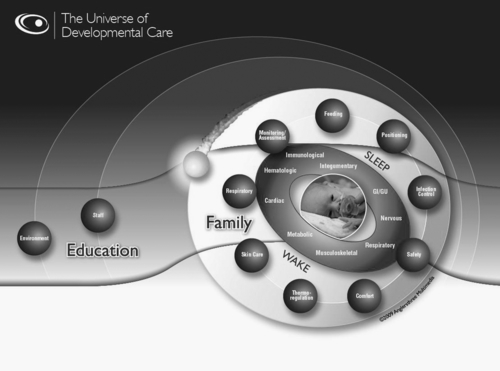

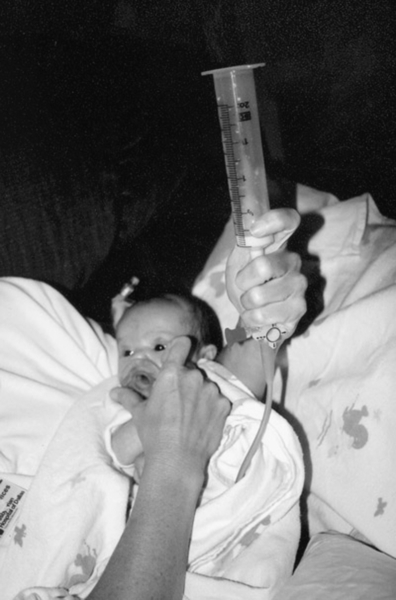

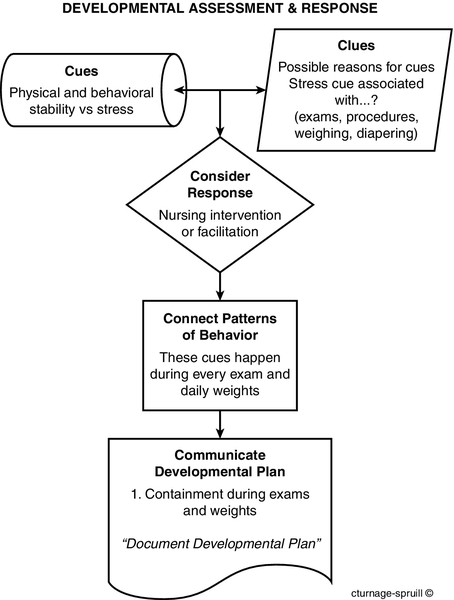

CHAPTER 11 2. Design a developmental care plan that respects and supports each infant’s unique needs as related to the environment, direct caregiving, parent support, and consistency of care. 3. Engage parents in active participation in their infant’s plan of care. Individualized developmentally supportive care (IDSC) is based on a philosophy of respect for the unique needs of preterm and high-risk infants susceptible to neurodevelopmental disadvantage in part due to the complex, atypical environment of the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and separation from the nurturing of parents (Fig. 11-1). Family-centered IDSC promotes a culture that supports family adaptation and involvement so that parents can be parents to their recovering infant. Preterm infants are especially vulnerable to cognitive, neuromotor, and neurosensory problems after discharge from the NICU. Fluctuations in cerebral circulation have been demonstrated in routine care procedures, and smaller than expected brain volumes at 36 to 40 weeks may play a significant role in increased morbidity in these infants. Altered cerebral oxygenation and blood volume measured with near-infrared spectroscopy have been exhibited during diaper changes, endotracheal tube suctioning, repositioning, physical exam, and nasogastric tube insertion (Limperopoulos et al., 2008). These brain changes are associated with early parenchymal abnormalities. A. The influence of early environmental, medical, and other perinatal atypical exposures is not clear even though developmental problems are more frequent in preterm infants after their NICU stay. Preterm infants display a different pattern of behavior on the NICU Network Behavioral Scale at term equivalent as compared with full-term infants (Pineda, et al., 2013). 1. Weaker orientation (P < 0.001). 2. Less ability to tolerate handling (P < 0.001). 3. Poorer self-regulation (P < 0.001). 4. Weaker reflexes (P < 0.001). 5. Higher stress response (P < 0.001). 6. More hypertonicity or hypotonia (P < 0.001). 7. Increased tendency toward excitability (P < 0.007). B. Important changes were observed in behaviors of preterm infants at 34 weeks postconceptional age compared to term equivalent. 1. Increasing arousal and excitability (P < 0.001). 2. Decreasing quality of movement (P = 0.006). 3. Increasing levels of hypertonia (P < 0.001) and decreasing hypotonia (P = 0.001). 4. Less lethargy (P < 0.001). C. Infants with brain injury demonstrated more excitability (P = 0.002). These neurobehavioral changes highlight the importance of interventions beginning immediately in the delivery room and throughout the NICU stay. A. Developmental care is more about the caregiver who: 2. Recognizes that health and neurodevelopmental problems occur at much higher frequency in preterm infants. 3. Realizes infants need early developmental support to reach optimal cognitive, physical, and social/emotional potential. 4. Commits to providing developmental support during all care and procedures; adapts the environment to better suit the individual infants. 5. Supports parents as essential to their infant’s physical and developmental progress from the moment of birth. B. The Universe of Developmental Care (UDC): expands Als’ Synactive Theory (Lawhon and Als, 2010) to accentuate the neurodevelopmental interface of the infant’s skin that links the baby to the environment of care and caregivers (Fig. 11-2). Aside from tactile opportunities, this shared surface is integrated with the entire sensory system (visual, auditory, vestibular, etc.) and affords the caregiver a practical approach to care through an interactive link to the actual body surface within the NICU context (Gibbins et al., 2008). 2. The planets represent aspects of care practices based on systematic reviews and meta-analyses of literature on developmental care and infant outcomes. Staff orbit protectively around the infant and family, accessing the shared care surface during nursing care customized to the infant’s individual requirements from knowledge of the available evidence-based practice symbolized by the planets that circumnavigate around the core (sun–infant). 3. The context for all interaction is the physical, human, and operations of the health care setting or NICU. The Milky Way exemplifies education as a persistent theme encompassing all orbital planes. Learning needs extend across staff, physicians, leaders, and families committed to safe, quality care and optimal outcomes. 4. The skin as the shared surface for interaction makes sense especially since it originates from the ectodermal layer during embryology, as does the brain. As the neurodevelopmental interface for care, the outer layer of the skin may be viewed as the brain’s surface. Obviously the brain cannot be observed directly in the NICU; therefore, caregivers use the skin or shared surface to operationalize or translate this model into bedside application of developmental care practices (Table 11-1). TABLE 11-1 Expanded Developmental Care Practices Within the Universe of Developmental Care Model From Gibbins, S., Hoath, S., and Coughlin, M.: The Universe of Developmental Care: A new conceptual model for application in the neonatal intensive care unit. Advances in Neonatal Care, 8(3):145, 2008. Reprinted with permission of Walter Kluwer Health. CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; NGT, nasogastric tube. A. Physical and behavioral assessment. 1. Assessment of stable or self-regulating behavior, as well as stress responses (Fig. 11-3), is ongoing during care and periods of rest and provides the information necessary for developmentally supportive care individual to each infant (Table 11-2). The framework for understanding preterm infant behavior is based on the work of Dr. Heidelise Als (1998). An infant’s observable channels of communication are used in a systematic assessment by caregivers to provide individualized, developmentally appropriate care. Als’ Synactive Theory proposes the hierarchical integration of subsystem development, integration with the other developing subsystems to eventual competent functioning without physiologic or autonomic stress and destabilization. a. Autonomic/visceral cues—changes in infant color, heart rate, respiratory patterns. b. Motor system—quality of tone and movement, posture. c. State system—quality and range of states, transitions between states. (1) Attention and interaction. (2) Self-regulation. 2. For example, competent functioning is demonstrated when Misha, now 35 weeks, is able to focus on suck, swallow, and breathing during an oral examination while maintaining physiologic and motor stability in a quiet, alert state. B. Individualized developmental care relies on both the moment-to-moment caregiver adaptations while in interaction with an infant and the formal plans based on infant assessment that provide overall guidance for care of that particular infant. Both are flexible, in that changes may need to be made based on infant responses at any given moment. 1. Care is dynamic and responsive, although dependent on the caregiver being completely in tune and in interaction with the infant rather than performing care as tasks on the infant (Fig. 11-4). Cues without context or an experience make it difficult for caregivers to apply appropriate interventions during care and in the overall plan of care. 2. The Five Constructs of Developmental Care (Fig. 11-5) can be used as a learning tool to guide the caregiver through the whole experience of the infant by the process of using their assessment within the context of the environment and situation to initiate interventions in the moment or use patterns of responses for developing plans of care. Finally, continuity and consistency among caregivers require that this information is communicated to the infant’s health care team and family to gather input on the developmental plan of care and link interventions to medical goals. a. The Five Constructs are a simple way to look at all the elements of operationalizing developmental principles into practical application (see Fig. 11-5). (1) Cues—observe infant cues and determine whether the behaviors indicate stability or stress. (2) Clues—check the situation and environment for clues to the observed behavior (Is the care stressful? Is the environment noisy?). (3) Consider—what is your best response given your knowledge of this infant and the cues/clues you identified within the best evidence available to the UDC. How is the shared interface useful in delivering care or interventions? (4) Connect—if you see a pattern of behavior, think about events that frequently trigger the infant’s stress cues (weighing on scale elicits extended arms, stiffly outstretched fingers, and oxygen saturation decreases from 4% to 6%). (5) Communicate—document and report the developmental plan based on your observation and analysis of individual behaviors and potential triggers to ensure consistent responses among caregivers.

Developmental Support

EARLY EXPERIENCE

WHAT IS DEVELOPMENTAL CARE?

Monitoring/Assessment

Feeding

Positioning

Vital sign assessment

Early feeds

Supine

Behavioral assessment

Trophic

Prone

Electrodes

Donor milk

Side-lying

Invasive catheters

Cue-based feeds

Flexion

Invasive/noninvasive monitoring

Nonnutritive sucking

Containment

CO2 monitor

Breast milk mouth care

Midline orientation (proper body alignment)

Saturation monitor

Enteral feedings

Boundaries

Cerebral monitor

Breast shields

Hand-to-mouth opportunity

Bottlefeed

Safety

Breastfeed

NGT feeds

Infection Control

Safety

Comfort

Occlusive dressings

Patient ID bands

Pain assessment practices

Handwashing

Enteral only/Parenteral only tubings

Pharmacological practices

Antibiotic use

Sucrose use

Prep solutions

Antimicrobial ointments

Gentle touch

Skin-to-skin

Jewelry policies

Infant security systems

Massage therapy

Postoperative practices

Gel mattresses

Sleep regulation

Environmental issues (ventilation, garbage disposal)

Environmental issues (flooring, equipment)

Environmental factors

Thermoregulation

Skin Care

Respiratory Care

Humidity control

Touch

Intubation practices

Temperature control

Soaps and emollients

CPAP interface

Swaddling

Bathing practices

Oxygen delivery systems

Plastic wrap

Cleansers and solutions

Instillations (surfactant, saline, nebulizers)

Room temperature

Adhesive removal

Suctioning practices

Solution temperature

Transdermal drug interface

Clothing

Topical anesthetics

Bedding

Wound care

Family

Staff

Environment

Satisfaction

Satisfaction

Light levels

Level of involvement

Knowledge

Noise levels

Knowledge

Autonomy

Cultural, racial, religious sensitivity

Autonomy

Leadership quality

OPERATIONALIZING DEVELOPMENTAL CARE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

11: Developmental Support

FIGURE 11-1 ■ High-risk infant in NICU environment. (Courtesy of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX; photographer Carol Turnage Spruill.)

FIGURE 11-2 ■ The Universe of Developmental Care. (Copyright 2009, Koninklijke Philips N.V. Used with Permission.)

FIGURE 11-3 ■ NICU infant demonstrating stress cues. (Courtesy of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX; photography by Carol Turnage Spruill.)

FIGURE 11-4 ■ Caregiver interacts with infant to promote enjoyment during a tube feeding. (Courtesy of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX; photography by Carol Turnage Spruill.)

FIGURE 11-5 ■ The Developmental Care Experience: Five Constructs©. (Courtesy of Carol Spruill-Turnage.)