Naturalistic Inquiry Designs

Key terms

Critical theory

Endogenous

Ethnography

Fieldwork

Grounded theory

Heuristic

Life history

Meta-analysis

Naturalistic

Narrative

Participatory action

Phenomenology

Using the language and thinking processes you learned in Chapter 8, we are now ready to explore naturalistic inquiry in more detail. This chapter highlights 10 specific designs of high relevance to health and human service–related concerns. These designs exemplify the wide variation in the naturalistic tradition, the different ways in which complex social phenomena are tackled, and how researchers working out of different naturalistic traditions organize the “10 essentials” of the research process (see Chapter 2). Although there are other naturalistic inquiry approaches that could be presented, examining these 10 designs will provide the foundational knowledge necessary to understand naturalistic inquiry overall.

First, let us reflect a bit on naturalistic inquiry and what we have learned thus far. Do you remember one of the basic principles of naturalist designs? You may recall our discussions in previous chapters that a fundamental principle of all naturalistic designs is that phenomena occur or are embedded in a context, natural setting, or field. The fundamental thinking process characterizing the research process is induction. As such, research processes are implemented and unfold in the identified context through the course of conducting fieldwork. Fieldwork refers to the basic activity that engages all investigators who work in the naturalistic tradition. In conducting fieldwork, the investigator enters an identified setting to experience and understand it without artificially altering or manipulating conditions. The purpose is to observe, understand, and come to know so that theory may be described, explained, and generated. This principle is essential to all naturalistic designs, but the way in which investigators come to know, describe, and explain phenomena differs among designs. That is, although each design shares the basic language and thinking processes discussed in Chapter 8, each design is also based in its own distinct philosophical tradition. As such, these designs differ in purpose, sequence, and investigator involvement (Box 10-1).

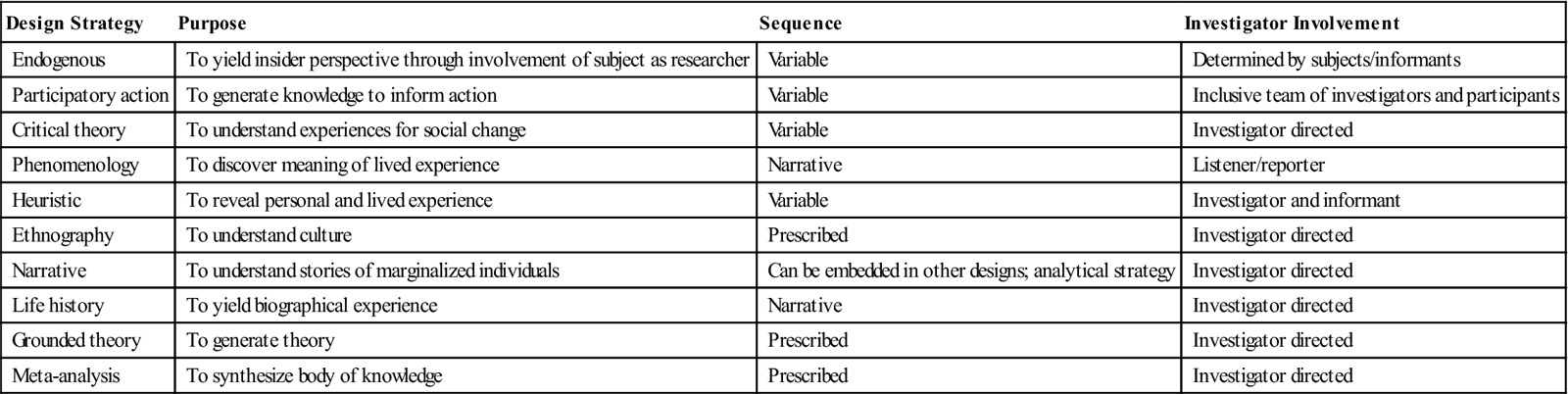

This chapter provides the basic framework of the 10 designs that have great methodological value for naturalistic inquiry in health and human services: endogenous, participatory action, critical theory, phenomenology, heuristic, ethnography, narrative, life history, grounded theory, and meta-analysis. Table 10-1 summarizes how these naturalistic designs compare in purpose, sequence, and investigator involvement. Remember as you read that the sequence by which the 10 essential thinking and action processes are applied is not fixed. Therefore, the essentials cannot be prescribed a priori for each of these 10 naturalistic designs.

TABLE 10-1

Basic Framework of 10 Designs in Naturalistic Inquiry

| Design Strategy | Purpose | Sequence | Investigator Involvement |

| Endogenous | To yield insider perspective through involvement of subject as researcher | Variable | Determined by subjects/informants |

| Participatory action | To generate knowledge to inform action | Variable | Inclusive team of investigators and participants |

| Critical theory | To understand experiences for social change | Variable | Investigator directed |

| Phenomenology | To discover meaning of lived experience | Narrative | Listener/reporter |

| Heuristic | To reveal personal and lived experience | Variable | Investigator and informant |

| Ethnography | To understand culture | Prescribed | Investigator directed |

| Narrative | To understand stories of marginalized individuals | Can be embedded in other designs; analytical strategy | Investigator directed |

| Life history | To yield biographical experience | Narrative | Investigator directed |

| Grounded theory | To generate theory | Prescribed | Investigator directed |

| Meta-analysis | To synthesize body of knowledge | Prescribed | Investigator directed |

Endogenous research

Endogenous research represents the most open-ended approach to research in the naturalistic tradition. This research is “conceptualized, designed, and conducted by researchers who are insiders of the culture, using their own epistemology and their own structure of relevance.”1 The unique feature of this design is the nature of investigator involvement. The investigator relinquishes control of a research plan and its implementation to those who are the target for or “subjects” of the inquiry. The “subjects” are primary investigators or co-investigators who work independently or with the investigator to determine the nature of the study and how it is to be shaped. The “subjects” and investigators make decisions about and participate in the building and testing of information as it emerges. Thus, in this type of research, the subject becomes a full participant in the process.

Endogenous research can be organized in a variety of ways and may include the use of any research strategy and technique in the naturalistic or experimental-type tradition or an integrated design. What makes endogenous research naturalistic is not its investigative structure but rather its paradigmatic framework; that is, the investigator views knowledge as emerging from individuals who know the best way to obtain information. Endogenous design is consistent with the contemporary notion of “emancipatory research,” a relatively new design category.2 It is also consistent with community-based participatory research and participatory action research, described later, which emphasize the importance of involving members in the community of interest in each research step, from query formulation to data collection and analysis.

These approaches as exemplified by endogenous research reject the traditional notion of individuals as research “subjects.” Rather, it views individuals as liberated not only as participants in investigator-facilitated inquiry but also as leaders in the generation and use of knowledge. The endogenous approach is based on a basic proposition developed by the social psychologist Kurt Lewin, as Argyris and Schon explained:

Causal inferences about the behavior of human beings are more likely to be valid and enactable when the human beings in question participate in building and testing them. Hence it aims at creating an environment in which participants give and get valid information, make free and informed choices (including the choice to participate), and generate internal commitment to the results of their inquiry.3

This design gives “knowing power” exclusively to the persons who are the participants of the inquiry. Thus, the endogenous approach is characterized by the absence of any predefined truths or structures. Because endogenous research is conducted by insiders, no external principles guide the selection of thought and action processes in the study itself. Also, because the researcher’s involvement is determined by the individuals who are the “subjects” of the investigation, the researcher may participate as an equal partner, or not at all, or somewhere between these two levels.

So how exactly does an endogenous design approach work? Let us examine a classic example of endogenous research on prison violence.

As you can surmise from this example, the investigator’s concerns in the endogenous research design include how to build and work with a team, how to relinquish control over process and outcome, and how to shape the group process to move the research team along in the study of themselves. These concerns rise from the nature of endogenous research and are distinct from other approaches.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research broadly refers to different types of action research approaches. These varied approaches to action research each reflect a different epistemological assumption and methodological strategy. However, all are “participative, grounded in experience, action-oriented,”4 and are founded in the principle that those who experience a phenomenon are the most qualified to investigate it. Similar to endogenous research, participatory action research involves individuals as first-person, second-person, and third-person4 participants in designing, conducting, and reporting research. By “first-person research,” we mean that individuals who experience the phenomenon of interest systematically reflect on their own lives. “Second-person research” refers to the initiation of an inquiry by a researcher who then branches out to collaborate directly with individuals and communities about a shared problem. In “third-person research” the collaborative nature is still essential, but the direct interaction between researcher and collaborator is not present. Communication takes place through other venues, such as written formats and reports.4 Consistent with others, we believe that the ideal participatory action inquiry includes all three perspectives and approaches.

The purpose of action research is to generate knowledge to inform responsive action. Researchers using a participatory framework usually work with groups or communities experiencing issues and needs related to health and welfare, disparities in health and access to health care, elimination of oppression and discrimination, equal opportunity, and social justice.

The concept of action research was first developed in the 1940s by Lewin, who blended experimental-type approaches to research with programs that addressed critical social problems. Social problems served as the basis for formulating a research purpose, question, and methodology. Therefore, each research step was connected to or involved with the particular organization, social group, or community that was the focus of inquiry and that was affected in some way by the identified problem or issue. More recently, others have expanded this approach to inquiry. The action research design is now used in planning and enacting solutions to community problems and service dilemmas.5

Action research is based on four principles or values (Box 10-2). The principle of democracy means that action research is participatory; that is, all individuals who are stakeholders in a problem or issue and its resolution are included in the research process. Equity ensures that all participants are equally valued in the research process, regardless of previous experience in research. Liberation suggests that action research is a design that is aimed at giving the power of inquiry to participants themselves, decreasing oppression, exclusion, and/or discrimination. Life enhancement positions action research as a systematic strategy that promotes growth, development, and fulfillment of participants of the process and the community they represent.

Participatory action research uses thinking and action processes from the experimental-type or naturalistic tradition or an integration of the two. Similar to endogenous design, there is no prescribed or uniform design strategy. Nevertheless, action research is consistent with naturalistic forms of inquiry in that all research occurs within its natural context. Also, most action research relies on action processes that are characteristically interpretive in nature.6

Let us examine the sequence in which the 10 research essentials are followed in a participatory action research study. Action research is best characterized as cyclical, beginning with the identification of a problem or dilemma that calls for action, moving to a form of systematic inquiry, and culminating in planning and using the findings of the inquiry. Each step is informed or shaped by the participants of the study. The purpose of the following participatory action study was to establish community programs to enhance the transition of adolescents with special health care needs from high school to work or higher education.7

Note that all members of the team were valued and contributed equally to the design, implementation, analysis, and application of the research.

Participatory action research is now used for many purposes, often involving advocacy for underserved groups. The pragmatic foundation combined with its democratic values render action research a useful tool for identifying, empirically supporting, and assessing needed change.

Critical theory

Critical theory is not a research method but a “worldview” that suggests both an epistemology and a purpose for conducting research. The debate continues on whether critical theory is a philosophical, political, or sociological school of thought. In essence, critical theory is a response to post-Enlightenment philosophies and positivism in particular. Critical theorists “deconstruct” the notion that there is a unitary truth that can be known by using one way or method.

We believe critical theory is a movement best understood by philosophers. Because critical theory is inspired by diverse schools of thought, including those informed by Marx, Hegel, Kant, Foucault, Derrida, and Kristeva, it is not a unitary approach. Rather, critical theory represents a complex set of strategies that are united by the commonality of sociopolitical purpose.8

Critical theorists seek to understand human experience as a means to change the world.9 The common purpose of researchers who approach investigation through critical theory is to come to know about social justice and human experience as a means to promote local change through global social change.

Critical theory was born in the Social Institute at the Frankfurt School in the 1920s. As the Nazi party gained power in Germany, critical theorists moved to Columbia University and developed their notions of power and justice, particularly in response to the hegemony of positivism in the United States. With a focus on social change, critical theorists came to view knowledge as power and the production of knowledge as “socially and historically determined.”10 Derived from this view is an epistemology that upheld pluralism, or a coming to know about phenomena in multiple ways. Furthermore, “knowing” is dynamic, changing, and embedded in the sociopolitical context of the times. According to critical theorists, no one objective reality can be uncovered through systematic investigation. Critical theorists and those who build on their work are frequently concerned with language and symbol as the vehicle through which to uncover multiple meanings and to examine power structures and their interactions.11

Critical theory is consistent with fundamental principles that bind naturalistic strategies together in one grand category, such as a view of informant as knower, the dynamic and qualitative nature of knowing, and a complex and pluralistic worldview. Furthermore, critical theorists suggest that research crosses disciplinary boundaries and challenges current knowledge generated by experimental-type methods. Because of the radical view posited by critical theorists, the essential step of literature review in the research process is primarily used as a means to understand the status quo. Thus the action process of literature review may occur before the research, but the theory derived is criticized, deconstructed, and taken apart to its core assumptions. The hallmark of critical theory, however, is its purpose of social change and empowerment of marginalized and oppressed groups. Critical theory relies heavily on interview and observation as methods through which data are collected. Strategies of qualitative data analysis are the primary analytical tools used in critical research agendas (as discussed in Chapter 20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Maruyama entered the prison environment as a collaborator and participant observer rather than as the research consultant, an important characteristic of endogenous research. As a collaborator, Maruyama deferred to the subjects of the investigation to determine the degree of investigator involvement. Two teams, composed of prisoners who had no formal education in research methods, held a series of group meetings and created purposes and plans of action that were important and meaningful to each group. Maruyama described the research in this way: “A team of endogenous researchers was formed in each of the two prisons. The overall objective of the project was to study interpersonal physical violence (fights) in the prison culture, with as little contamination as possible from academic theories and methodologies. The details of the research were left to be developed by the inmate researchers.”

Maruyama entered the prison environment as a collaborator and participant observer rather than as the research consultant, an important characteristic of endogenous research. As a collaborator, Maruyama deferred to the subjects of the investigation to determine the degree of investigator involvement. Two teams, composed of prisoners who had no formal education in research methods, held a series of group meetings and created purposes and plans of action that were important and meaningful to each group. Maruyama described the research in this way: “A team of endogenous researchers was formed in each of the two prisons. The overall objective of the project was to study interpersonal physical violence (fights) in the prison culture, with as little contamination as possible from academic theories and methodologies. The details of the research were left to be developed by the inmate researchers.”

Using the principles of action research and first-, second-, and third-person approaches, the investigators first identified the stakeholders involved in this issue. They included adolescents and their parents, educators, health care providers, employers, and policy makers. To ensure that the research plan reflected the underlying principles of democracy and equity, the investigators convened a group made up of representatives from each of the stakeholder groups. This group became the core participatory researchers. These participatory researchers and the two investigators discussed the research problem and collaboratively negotiated and structured the research method. Focus groups were identified as the primary data collection method, so all team members were trained in this approach. Focus groups of each of the stakeholder groups examined the service needs perceived by each group. Each focus group was facilitated by two members of the participatory team. Data were collected and analyzed by the participatory team. The team reported the findings to planning groups consisting of the same stakeholder groups. A comprehensive service plan was developed, implemented, and evaluated by the participatory action team.

Using the principles of action research and first-, second-, and third-person approaches, the investigators first identified the stakeholders involved in this issue. They included adolescents and their parents, educators, health care providers, employers, and policy makers. To ensure that the research plan reflected the underlying principles of democracy and equity, the investigators convened a group made up of representatives from each of the stakeholder groups. This group became the core participatory researchers. These participatory researchers and the two investigators discussed the research problem and collaboratively negotiated and structured the research method. Focus groups were identified as the primary data collection method, so all team members were trained in this approach. Focus groups of each of the stakeholder groups examined the service needs perceived by each group. Each focus group was facilitated by two members of the participatory team. Data were collected and analyzed by the participatory team. The team reported the findings to planning groups consisting of the same stakeholder groups. A comprehensive service plan was developed, implemented, and evaluated by the participatory action team. A researcher is interested in understanding the relationship between clients who are substance abusers and formal service providers and the influence of this relationship on the outcome of therapeutic interventions. First, using a critical theory perspective, the researcher would review the literature critically. Of particular importance for the critical theorist would be an examination of the underlying assumptions in the language and textual symbols that reflect a power imbalance based on race, class, and gender differences between client and practitioner. In critical theory, this imbalance is presumed to have an effect of oppressing the client while elevating the status, control, and power of the service provider. Second, the researcher would use a range of strategies based in naturalistic inquiry to observe and explore the relationship of client and service provider from the perspectives of both parties. Third, the understandings derived from the research would be used to promote social change, with a particular focus on advancing social justice and equality for clients.

A researcher is interested in understanding the relationship between clients who are substance abusers and formal service providers and the influence of this relationship on the outcome of therapeutic interventions. First, using a critical theory perspective, the researcher would review the literature critically. Of particular importance for the critical theorist would be an examination of the underlying assumptions in the language and textual symbols that reflect a power imbalance based on race, class, and gender differences between client and practitioner. In critical theory, this imbalance is presumed to have an effect of oppressing the client while elevating the status, control, and power of the service provider. Second, the researcher would use a range of strategies based in naturalistic inquiry to observe and explore the relationship of client and service provider from the perspectives of both parties. Third, the understandings derived from the research would be used to promote social change, with a particular focus on advancing social justice and equality for clients.