Therapeutic Communication and Relationships

Listen

When I ask you to listen to me and you start giving advice, you have not done what I asked.

When I ask you to listen to me and you begin to tell me why I shouldn’t feel that way, you are trampling on my feelings.

When I ask you to listen to me and you feel you have to do something to solve my problem, you have failed me, strange as that may seem.

Listen! All I asked was that you listen, not talk or do—just hear me.

And I can do for myself; I’m not helpless. Maybe discouraged and faltering, but not helpless.

When you do something for me that I can and need to do for myself, you contribute to my fear and weakness.

But, when you accept as a simple fact that I do feel what I feel, no matter how irrational, then I can quit trying to convince you and can get about the business of understanding what’s behind this irrational feeling.

And when that’s clear, the answers are obvious and I don’t need advice.

So, please listen and just hear me. And, if you want to talk, wait a minute for your turn; and I’ll listen for you.

—Anonymous

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Explain the process of communication.

Distinguish the factors that influence communication.

Describe the importance of assessing nonverbal communication.

Articulate the relationship between comfort zones and effective communication skills.

Identify factors that contribute to ineffective communication.

Compare and contrast social and therapeutic communication.

Formulate a list of therapeutic communication techniques.

Demonstrate an understanding of the importance of confidentiality in the clinical setting.

Develop a sample process recording in the clinical setting.

Construct a list of the essential conditions for a therapeutic relationship as described by Carl Rogers.

Describe the six subroles of the psychiatric–mental health nurse identified by Hildegard Peplau.

Explain the phases of a therapeutic one-to-one relationship.

Articulate a list of potential boundary violations that may occur during a therapeutic relationship.

Key Terms

Comfort zones

Communication

Countertransference

Nonverbal communication

Parataxic distortion

Process recording

Professional boundaries

Social communication

Therapeutic communication

Therapeutic relationship

Transference

Verbal communication

Zones of distance awareness

Relationships between psychiatric–mental health nurses and clients are established through communication and interaction. Communication between two human beings can be difficult and challenging. When we communicate, we share significant feelings with those to whom we are relating. If the interaction facilitates growth, development, maturity, improved functioning, or improved coping, it is considered therapeutic (Rogers, 1961). This chapter discusses the psychiatric–mental health nurse’s ability to establish a therapeutic relationship with the client using a biopsychosocial approach.

Communication

Communication refers to the giving and receiving of information involving three elements: the sender, the message, and the receiver. The sender prepares or creates a message when a need occurs and sends the message to a receiver or listener, who then decodes it. The receiver may then return a message or feedback to the initiator of the message.

Factors Influencing Communication

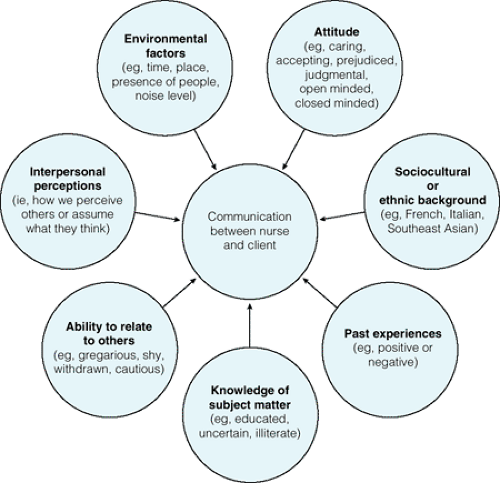

Communication is a learned process influenced by a person’s attitude, sociocultural or ethnic background, past experiences, knowledge of subject matter, and ability to relate to others. Interpersonal perceptions also affect our ability to communicate because they influence the initiation and response of communication. Such perception occurs through the senses of sight, sound, touch, and smell. Environmental factors that influence communication include time, place, the number of people present, and the noise level (Fig. 11-1).

Attitude

Attitudes are developed in various ways. They may be the result of interaction with the environment; assimilation of others’ attitudes; life experiences; intellectual processes; or a traumatic experience. Attitudes can be described as accepting, caring, prejudiced, judgmental, and open or closed minded. An individual with a negative or closed-minded attitude may respond with, “It won’t work” or “It’s no use trying.” Conversely, the individual with a positive or open-minded attitude may state, “Why not try it? We have nothing to lose.”

Sociocultural or Ethnic Background

Various cultures and ethnic groups display different communication patterns. For example, some people of French or Italian heritage often are gregarious and talkative, willing to share thoughts and feelings. Some people from Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand or Laos, who often are quiet and reserved, may appear stoic and reluctant to discuss personal feelings with persons outside their families. However, with our “cultural melting pot” society, variations do exist, so generalizations should not be made.

Past Experiences

Previous positive or negative experiences influence one’s ability to communicate. For example, teenagers who have been criticized by parents whenever attempting to express any feelings may develop a disturbed self-concept and feel that their opinions are not worthwhile. As a result, they may avoid interacting with others, become indecisive when asked to give an opinion, or agree with others to avoid what they perceive to be criticism or confrontation. Persons with a developmental disability or children may often try to give the expected “correct” response to get approval

from the interviewer, although the answers may in fact not be true or representative of the actual situation.

from the interviewer, although the answers may in fact not be true or representative of the actual situation.

Knowledge of Subject Matter

A person who is well educated or knowledgeable about certain topics may communicate with others at a high level of understanding. The receiver of the message may be unable to comprehend the message, or consider the sender to be a “know-it-all expert.” As a result of this misperception, the receiver, not wanting to appear ignorant, may neglect to ask questions or even nod in agreement and may not receive the correct information.

Ability to Relate to Others

Some people are “natural-born talkers” who claim to have “never met a stranger.” Others may possess an intuitive trait that enables them to say the right thing at the right time and relate well to people. “I feel so comfortable talking with her,” “She’s so easy to relate to,” and “I could talk to him for hours” are just a few comments made about people who have the ability to relate well with others. Such an ability can also be a learned process, the result of practicing effective communicative skills over time.

Interpersonal Perceptions

Interpersonal perceptions are mental processes by which intellectual, sensory, and emotional data are organized logically or meaningfully. Satir (1995) warns of looking without seeing, listening without hearing, touching without feeling, moving without awareness, and speaking without meaning. In other words, inattentiveness, disinterest, or lack of use of one’s senses

during communication can result in distorted perceptions of others. The following passage reinforces the importance of perception: “I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I said” (Lore, 1981).

during communication can result in distorted perceptions of others. The following passage reinforces the importance of perception: “I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I said” (Lore, 1981).

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors such as time, place, number of people present, and noise level can influence communication. Timing is important during a conversation. Consider the child who has misbehaved and is told by his mother, “Just wait until your father gets home.” By the time the father does arrive home, the child may not be able to relate to him regarding the incident that occurred earlier. Some people prefer to “buy time” to handle a situation involving a personal confrontation. They want time to think things over or “cool off.”

The place in which communication occurs, as well as the number of people present and noise level, has a definite influence on interactions. A subway, crowded restaurant, or grocery store would not be a desirable place to conduct a disclosing, serious, or philosophic conversation.

Types of Communication

Communication is the process of conveying information verbally, through the use of words, and nonverbally, through gestures or behaviors that accompany words. Nonverbal communication also can occur in the absence of spoken words.

Verbal Communication

An individual uses verbal communication to convey content such as ideas, thoughts, or concepts to one or more listeners. Five levels of interpersonal, verbal communication were discussed in Chapter 2. Open, honest communication occurs in therapeutic relationships when the content of verbal communication is congruent with the speaker’s nonverbal behavior (that is, when words match gestures and behaviors). To effectively use verbal communication, one must use the spoken word as a communication tool while being mindful of its potential to affect outcomes. Verbal communication allows us to present ourselves to each other, using words to convey the most complex dimensions of ourselves—aspects that are not obvious from appearance or action (Frazier, 2001).

Nonverbal Communication

As presented in Chapter 9, clients may reveal their emotions, feelings, and mood through their general appearance or their behavior, termed nonverbal communication. Nonverbal communication is said to reflect a more accurate description of one’s true feelings because people have less control over nonverbal reactions. Vocal cues, gestures, physical appearance, distance or spatial territory, position or posture, touch, and facial expressions are nonverbal communication techniques used in the psychiatric–mental health clinical setting.

Vocal Cues

Pausing or hesitating while conversing, talking in a tense or flat tone, or speaking tremulously are vocal cues that can agree with or contradict a client’s verbal message. Speaking softly may indicate a concern for another, whereas speaking loudly may be the result of feelings of anger or hostility. For example, a person who is admitted to the hospital for emergency surgery may speak softly but tremulously, stating, “I’m okay. I just want to get better and go home as soon as possible.” The nonverbal cues should indicate to the nurse that the client is not okay and the client’s feelings need to be explored.

Gestures

Pointing, finger tapping, winking, hand clapping, eyebrow raising, palm rubbing, hand wringing, and beard stroking are examples of nonverbal gestures that communicate various thoughts and feelings. They may betray feelings of insecurity, anxiety, apprehension, power, enthusiasm, eagerness, or genuine interest.

Physical Appearance

People who are depressed may pay little attention to their appearance. They may appear unkempt and unconsciously don dark-colored clothing, reflecting their depressed feelings. Persons who are confused or disoriented may forget to put on items of clothing, put them on inside out, or dress inappropriately. Weight gain or weight loss also may be a form of nonverbal communication. People who exhibit either may be experiencing a low self-concept or feelings of anxiety, depression, or loneliness. The client with mania may dress in brightly colored clothes with several items of jewelry and excessive make-up. People with a positive self-concept may communicate such a feeling by appearing neat, clean, and well dressed.

Box 11.1: Four Zones of Distance Awareness or Spatial Territory

Intimate zone: Body contact such as touching, hugging, and wrestling

Personal zone: 1½ to 4 feet; “arm’s length”; some body contact such as holding hands; therapeutic communication occurs in this zone

Social zone: 1 to 12 feet; formal business; social discourse

Public zone: 12 to 25 feet: no physical contact; minimal eye contact; people remain strangers

Distance or Spatial Territory

Adult, middle-class Americans commonly use four zones of distance awareness (Hall, 1990). These four zones include the intimate, personal, social, and public zones (Box 11-1). Actions that involve touching another body, such as lovemaking and wrestling, occur in the intimate zone. The personal zone refers to an arm’s length distance of approximately 1½ to 4 feet. Physical contact, such as hand holding, still can occur in this zone. This is the zone in which therapeutic communication occurs. The social zone, in which formal business and social discourse occurs, occupies a space of 4 to 12 feet. The public zone, in which no physical contact and little eye contact occurs, ranges from 12 to 25 feet. People who maintain communication in this zone remain strangers.

Position or Posture

The position one assumes can designate authority, cowardice, boredom, or indifference. For example, a nurse standing at the foot of a client’s bed with arms folded across chest gives the impression that the nurse is in charge of any interaction that may occur. A nurse slumped in a chair, doodling on a pad, gives the appearance of boredom. Conversely, a nurse sitting in a chair, leaning forward slightly, and maintaining eye contact with a client gives the impression that the nurse is interested in what the client says or does (Fig. 11-2).

Touch

Reactions to touch depend on age, sex, cultural background, interpretation of the gesture, and appropriateness of the touch. The nurse should always exercise caution when touching people. For example, hand shaking, hugging, holding hands, and kissing typically denote positive feelings for another person. The client with depression or who is grieving may respond to touch as a gesture of concern, whereas the client who is sexually promiscuous may consider touching an invitation to sexual advances. A child suffering from abuse may recoil from the nurse’s attempt to comfort, whereas a person who is dying may be comforted by the presence of a nurse sitting by the bedside silently holding his or her hand. A psychotic client may misinterpret touch as a threat or an attack and may react accordingly.

Facial Expression

A blank stare, startled expression, sneer, grimace, and broad smile are examples of facial expressions denoting one’s innermost feelings. For example, the client with depression seldom smiles. Clients experiencing dementia often present with apprehensive expressions because of confusion and disorientation. Clients experiencing pain may grimace if they do not receive pain medication or other interventions to reduce their pain.

Social and Therapeutic Communication

Two types of communication—social and therapeutic—may occur when the nurse works with clients or

families who seek help for physical or emotional needs. Social communication occurs daily as the nurse greets the client and passes the time of day with what is referred to as “small talk.” Comments such as “Good morning. It’s a beautiful day out,” “How are your children?” and “Have you heard any good jokes lately?” are examples of socializing. During a therapeutic communication, the nurse helps or encourages the client to communicate perceptions, fears, anxieties, frustrations, expectations, and increased dependency needs. “You look upset. Would you like to share your feelings with someone?” “I’ll sit with you until the pain medication takes effect,” and “No, it’s true that I don’t know what it is like to lose a husband, but I would think it would be one of the most painful experiences one might have,” are just a few examples of therapeutic communication with clients.

families who seek help for physical or emotional needs. Social communication occurs daily as the nurse greets the client and passes the time of day with what is referred to as “small talk.” Comments such as “Good morning. It’s a beautiful day out,” “How are your children?” and “Have you heard any good jokes lately?” are examples of socializing. During a therapeutic communication, the nurse helps or encourages the client to communicate perceptions, fears, anxieties, frustrations, expectations, and increased dependency needs. “You look upset. Would you like to share your feelings with someone?” “I’ll sit with you until the pain medication takes effect,” and “No, it’s true that I don’t know what it is like to lose a husband, but I would think it would be one of the most painful experiences one might have,” are just a few examples of therapeutic communication with clients.

Table 11-1 compares social and therapeutic communication as discussed by Purtilo and Haddad (2002). Purtilo also recommends the following approaches and techniques for nurses participating in a therapeutic interaction:

Translate any technical information into layperson’s terms.

Clarify and restate any instructions or information given. Clients usually do not ask doctors or nurses to repeat themselves.

Display a caring attitude.

Exercise effective listening.

Do not overload the listener with information.

| ||||||||||||||||

Additional therapeutic communication techniques, and examples of how a nurse might use them in conversation with a client, are provided in Table 11-2.

Confidentiality During Communication

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree