The United States Military Health System

Policy Challenges in Wartime and Peacetime

John S. Murray and Mary W. Chaffee

“Our team provides optimal health services in support of our nation’s military mission—anytime, anywhere.”

—Military Health System Mission

Members of the U.S. uniformed services have received Federal health benefits for more than 200 years since Congress first enacted legislation requiring that medical care be provided for ill soldiers and sailors. Over the years, Congress added provisions that care be provided for military families, military retirees and their family members, and others (Department of Defense [DOD], 2007).

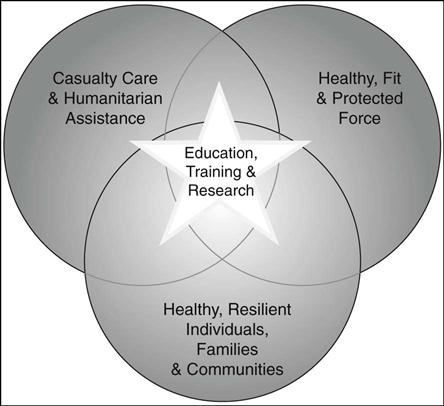

The Military Health System (MHS) has dual missions (Figure 19-1):

• A health care benefits mission focused on providing care and support to members of the uniformed services, their family members, and others entitled to DOD health services (Hosek and Cecchine, 2001).

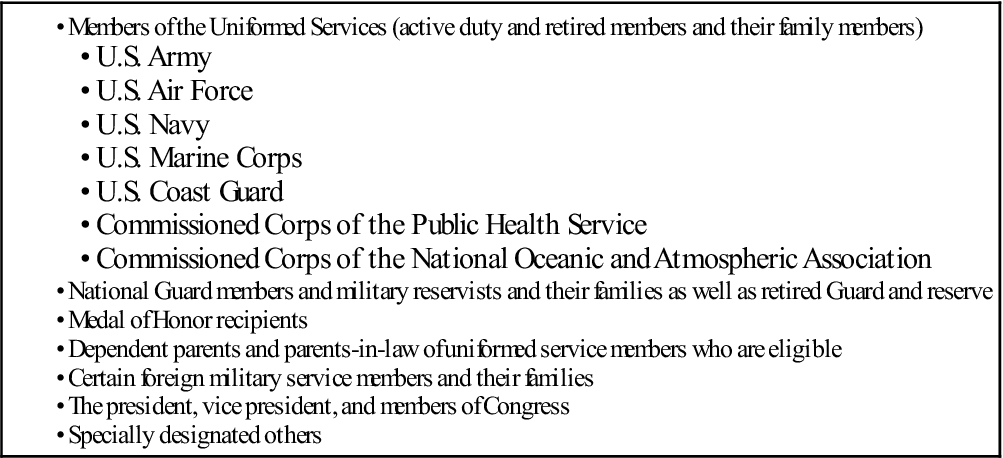

In 2009, the MHS cared for approximately 9.5 million eligible beneficiaries around the world (Table 19-1). It is staffed by about 133,000 personnel consisting of 86,000 military and 47,000 civilian personnel working at 59 military hospitals, 413 medical clinics, and 413 dental clinics worldwide (TRICARE Management Activity, 2009). Care in the MHS is provided in diverse settings including major medical centers, outpatient clinics, aircraft carriers, submarines, medical evacuation aircraft, combat medical units (tents), and other environments.

TABLE 19-1

Groups Eligible for Care in the U.S. Military Health System

Sources: TRICARE.mil/mybenefit/home/overview/eligibility; Military Medicare care: Questions and answers, March 7, 2007, CRS Report for Congress (RL33537).

Organization of Care

Direct Care

Care for active duty personnel, and for others when space is available, is provided through military medical facilities known as the direct care system. Care for wounded military personnel begins in the direct care system. This entails providing care in theatre (the area of combat operations), and transport back to the U.S. Rehabilitation may continue in the hospitals and clinics operated by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Collaboration between the DOD and VA is vital; significant coordination is required for continuity of care for military members.

Tricare

Hospitals and clinics operated by the military services do not have adequate capacity to provide all the care required by eligible beneficiaries so a civilian network of care has been developed to augment the direct care system. TRICARE is the health benefit plan for military beneficiaries (those who are entitled by law to receive care in the DOD health system). TRICARE includes multiple program options to meet the medical and dental needs of beneficiaries. TRICARE Prime is similar to a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) and uses military and civilian facilities. TRICARE Extra is structured like a Preferred Provider Organization (PPO), and TRICARE Standard is a fee-for-service option. TRICARE For Life is an option for military retirees enrolled in Medicare Part B (Burelli, 2003). The DOD also manages dental and pharmacy benefit programs.

Humanitarian Efforts and Medical Diplomacy

The MHS also provides disaster relief and humanitarian assistance around the world. Humanitarian assistance is an element of national diplomacy in the war on terrorism. It helps to build bridges to peace around the world (DOD MHS, 2008; 2009). The military’s hospital ships, U.S. Naval Ship (USNS) COMFORT and USNS MERCY, have responded to numerous crises including the 2004 Asian tsunami. Military medical personnel have carried out humanitarian missions in Honduras, Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Bangladesh, and many other areas, bringing much-needed care to underserved areas and in response to disaster (Caring for America’s Heroes, 2008).

Leadership and Vision

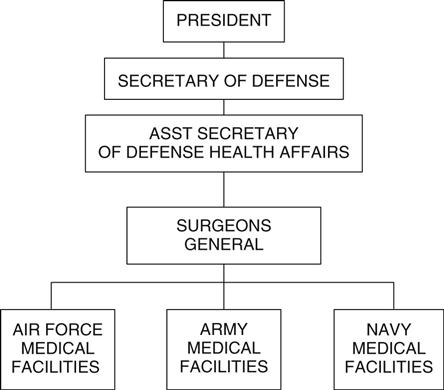

MHS leadership consists of more than 36 senior military and civilian health care leaders including the Surgeons General of the Air Force, Army, and Navy (the chief executive officers of their respective organizations) (DOD MHS, 2008, 2009) (Figure 19-2). The MHS leadership structure includes career military and civilian political appointees. For example, the U.S. president is responsible for nominating senior leaders to become the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs and the Surgeons General of the Air Force, Army, and Navy. Following a nomination, Congress is responsible for confirming the selection. Although the MHS is a military system, policy shifts occur when administrations change, as a result of the civilian political leadership.

The MHS Budget

Each year, the National Defense Authorization Act is passed by Congress specifying the budget for DOD including the MHS through the Defense Health Program (DHP). The military medical departments, the MHS financial management staff along with the DOD comptroller and key members of Congressional oversight committees, work to develop an executable budget. Following preparation of the budget, each military Surgeon General, along with other leaders from the MHS, testifies before the Senate Armed Services Committee outlining accomplishments from the past year and their plan for the next year’s budget execution. DHP funding provides for the delivery of health services and also funds the education and training of medical personnel, research, procurement of medical equipment for military hospitals and clinics, and other select health care activities.

The 2009 defense appropriations bill included increases for traumatic brain injury (TBI) and psychological health of military personnel returning from war. The $24.6 billion funding represents an approximate 9% increase from the previous year. This growth in the budget represents a commitment on the part of MHS and Congressional leadership to address this important issue (DOD, 2009).

Major Policy Issues in the MHS

Combat Injuries Causing PTSD and TBI

Following September 11, 2001, two major military campaigns were initiated in response to the terrorist attacks on the U.S. The first, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan, began in October 2001. The second, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) in Iraq, commenced in March 2003. Since 2001, military members have been deployed for long periods of time in extreme combat conditions with subsequent exposure to life-changing experiences. These events have placed them at great risk for developing a variety of mental health conditions including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

PTSD

Military personnel are exposed to numerous psychological and social stressors that can be immediate, acute, and chronic in nature. Military personnel with PTSD often relive their stressful experiences such as exposure to combat, death of fellow comrades, devastated communities, and homeless refugees, through nightmares and flashbacks. Not only do they have concerns about their own safety in the war zone; they also worry about the well-being of family members at home (GAO, 2008a; Gahm & Lucenko, 2007; Romanoff, 2006). Affected service members often feel detached and estranged, resulting in family relationship disruptions. It is estimated that as many as 20% of service members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have screened positive for PTSD or other behavioral health symptoms such as depression and anxiety (GAO, 2008a; Gahm & Lucenko, 2007).

The DOD developed and implemented standards for screening military personnel for mental health conditions related to deployment. However, policies requiring health care providers to review medical records to screen for conditions were inconsistent. To address this deficit, the DOD issued a policy establishing baseline mental health standards military personnel must meet in order to deploy to support the wartime mission. This policy recognized the predeployment mental health assessment as a mechanism for screening personnel within 60 days before an individual deploys (GAO, 2008a). To further improve care for military personnel serving in areas of conflict, a postdeployment health assessment was also developed to provide screening 90 to 180 days following return from combat. This tool affords the DOD the ability to obtain information on service members’ health concerns that emerge over time after return from deployment (Gahm & Lucenko, 2007).

TBI

Military personnel serving in OEF and OIF are also at risk for exposure to physical injury related to combat. TBI is one of the most frequently reported injuries among service members in Iraq and Afghanistan and may account for as much as 20% to 30% of battlefield-related injuries (GAO, 2008a). Exposure to improvised explosive devices; motor vehicle accidents; gunshot injuries to the face, head, and neck; and falls are the mechanisms of injury responsible for the greatest number of cases of TBI (Martin et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2008). Improved effectiveness of body armor in protecting military personnel from injuries that would have resulted in death in prior conflicts is likely the reason for the increasing numbers of TBI cases reported (Warden, 2006). With this high survival rate has come policy issues related to identifying and meeting the demand for care of patients with TBI including training and research as part of the policy solutions.

In 2007, the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) was reorganized to work with the newly established Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury. The purpose of this was to provide evaluation, treatment, and follow-up care for military personnel on active duty or retired from military service who have a brain injury. DVBIC’s mission is accomplished through patient care, educational programs, and clinical research conducted to identify evidence-based care and treatment for patients with TBI (DVBIC, 2009).

Research is aimed at identifying the effectiveness of various medications in treating or eliminating the effects of TBI such as headaches, confusion, agitation, and alterations in memory and cognition. In collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), efforts are underway to follow TBI patients over time to identify long-term problems associated with TBI. Research initiatives are critical for providing data on the consequences of TBI injuries so MHS policymakers can base policy on evidence (DVBIC, 2009).

Another critical issue for policymakers, as with PTSD, is appropriate screening of OEF/OIF veterans for TBI. In collaboration with the DVBIC, the VA is refining a tool to screen all veterans for TBI. Training has been established for providers to ensure that screening protocols are used accurately and that veterans are properly evaluated and treated for TBI (GAO, 2008b). Beginning in 2008, the DOD required screening for TBI in all military personnel who were identified for combat duty (GAO, 2008a).

Suicide

Suicide rates among both active duty military members and veterans continue to rise despite efforts by the DOD to address the problem (Kuehn, 2009; Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008). It is estimated that approximately 37% of military personnel returning from Iraq and Afghanistan have challenges with their mental health (Seal et al., 2009). The military has grappled for years with the issue of stigma associated with seeking mental health services. Service members may have reservations about disclosing symptoms because of the possible implications for their careers (Kuehn, 2009; Hill et al., 2006). Current policies need to be examined and new policies need to be created that encourage those who need help to seek mental health care without fear of risk to their professional livelihood and with certainty that they can seek treatment in a confidential manner (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008).

Base Realignment and Closure/Integration

Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) is mandated by Congress and serves as a mechanism by which a major reorganization of military installations, including health services, occurs periodically. A major goal of BRAC for the MHS is planning for the effective and efficient delivery of health care services for all beneficiaries—especially the care for casualties returning from Iraq and Afghanistan (Murray, 2009). From a health care perspective, under BRAC law the Air Force, Army, and Navy are responsible for working jointly to ensure that health care resources are properly utilized to achieve the MHS mission. BRAC presents an opportunity for greater integration and coordination of health care assets. This more integrated health system is expected to improve effectiveness and efficiency (Murray, 2009).

Congress has directed the MHS to establish and maintain partnerships with other federal agencies such as the VA and Health and Human Services (HHS) as well as explore similar partnerships with the private health care sector (Murray, 2009). The MHS and VA are currently coordinating health care delivery services working through barriers that exist like different computer systems. In fact, in the fiscal year 2010 DOD budget, funding was specifically set aside for the DOD and the VA to work collaboratively to develop an interoperable electronic health care record.

Personnel

Staff in military hospitals consists of military, civilian, and contracted civilian personnel. A major personnel policy issue is the congressional direction to shrink the size of military staff and convert their positions to civilian ones. Determining the appropriate mix of military and civilian personnel to support U.S. forces during a war or other conflict and to provide high-quality, cost-effective medical care during peacetime has not occurred without controversy. The conversion has begun, but each military department took a different approach. At the end of fiscal year 2007, the Air Force projected that 1216 military positions would be converted. During the same time period, the Navy planned to change 2675 positions and the Army approximately 1588 (DOD, 2007).

There are concerns with this personnel policy. Uniformed health care professionals are viewed as the foundation of the MHS because of their training for missions such as wartime and disaster response. Many MHS leaders worry that significant reductions in military medical personnel will decrease the agility needed to respond to wartime and disaster response missions. Military to civilian conversions have also contributed to unfilled vacancies. With the increasing shortage of health care personnel (e.g., nurses) and strong competition with the civilian sector for health care providers, the MHS is confronted with significant challenges in filling these vacancies. Recruiting and retaining highly qualified health care professionals is becoming more challenging for all of the military services, which have been challenged for years by chronic shortages in certain essential health care specialties (e.g., critical care, internal medicine, and orthopedic surgery) that are required for sustained operational readiness. Further complicating personnel shortages, military departments compete not only with the civilian health care sector for qualified medical personnel, but also with each other (DOD, 2007).

Tobacco Use

Researchers are reporting that not only are military personnel who are deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan at increased risk for injury related to dangers inherent in war, they are also at risk for diseases associated with smoking (Smith & Malone, 2009). Use of tobacco products causes both short-term and long-term complications such as reducing overall general fitness; pulmonary diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; oral, pancreatic, and lung cancers; and cardiovascular diseases such as heart attack and stroke (Institute of Medicine, 2009). Despite the DOD’s attempts to curtail tobacco use in those serving in the military, use of tobacco products continues to remain high (Smith & Malone, 2009). DOD policies have focused on smoking-cessation programs, smoke-free environments, and efforts to either prohibit the sale of tobacco products or restrict the sale of such products on military installations (Institute of Medicine, 2009; Smith & Malone, 2009). However, this issue remains a significant health concern that impedes the ability of military personnel to be medically ready to serve. In order to prevent illness of military personnel as a result of tobacco use, stronger policies addressing comprehensive tobacco-free environments and wide-ranging tobacco-control programs are needed (Institute of Medicine, 2009; Smith & Malone, 2009).

Emergency Contraception

Another policy issue being analyzed in the MHS is the availability of emergency contraception (EC) in military hospitals. Although approved by the FDA since 1997 as a safe and essential method for avoiding unplanned pregnancies following unprotected sexual intercourse, EC remains underutilized in both the military and civilian health care sectors (Chung-Park, 2008). Unintentional pregnancies have implications on the military readiness of women serving in uniform. The MHS is considering policy that will make EC readily available to all female service members at all locations where they serve as well as examining the impact such a policy might have on their health and medical readiness (DOD MHS, 2009).

For a list of related websites, please refer to your Evolve Resources at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Mason/policypolitics/

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree