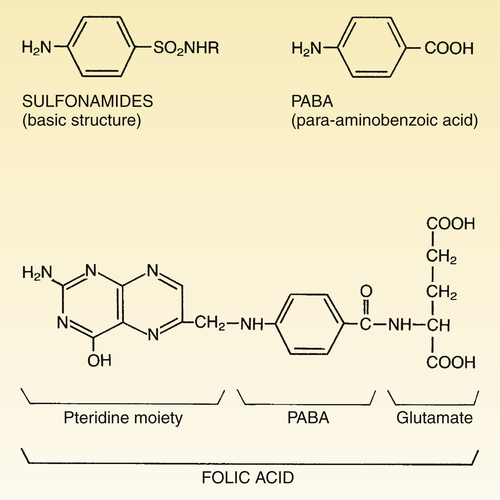

CHAPTER 88 Sulfonamides suppress bacterial growth by inhibiting synthesis of folic acid (folate), a compound required by all cells to make DNA, RNA, and proteins. The steps in folate synthesis are shown in Figure 88–2. As indicated, sulfonamides block the step in which PABA is combined with pteridine to form dihydropteroic acid. Because of their structural similarity to PABA, sulfonamides act as competitive inhibitors of this reaction. Sulfonamides are usually bacteriostatic. Accordingly, host defenses are essential for complete elimination of infection. Sulfonamides are often preferred drugs for acute infections of the urinary tract. About 90% of these infections are due to Escherichia coli, a bacterium that is usually sulfonamide sensitive. Of the sulfonamides available, sulfamethoxazole (in combination with trimethoprim) is generally favored. Sulfamethoxazole has good solubility in urine and achieves effective concentrations within the urinary tract. Urinary tract infections and their treatment are discussed in Chapter 89. The most severe hypersensitivity response to sulfonamides is Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a rare reaction with a mortality rate of about 25%. Symptoms include widespread lesions of the skin and mucous membranes, combined with fever, malaise, and toxemia. The reaction is most likely with long-acting sulfonamides, which are now banned in the United States. Short-acting sulfonamides may also induce the syndrome, but the incidence is low. To minimize the risk of severe reactions, sulfonamides should be discontinued immediately if skin rash of any sort is observed. In addition, sulfonamides should not be given to patients with a history of hypersensitivity to chemically related drugs, including thiazide diuretics, loop diuretics, and sulfonylurea-type oral hypoglycemics—although the risk of cross-reactivity with these agents is probably low (see below, under Drug Interactions).

Sulfonamides and trimethoprim

Sulfonamides

Basic pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Sites of action of sulfonamides and trimethoprim.

Sites of action of sulfonamides and trimethoprim.

Sulfonamides and trimethoprim inhibit sequential steps in the synthesis of tetrahydrofolic acid (FAH4). In the absence of FAH4, bacteria are unable to synthesize DNA, RNA, and proteins.

Therapeutic uses

Urinary tract infections.

Adverse effects

Hypersensitivity reactions.