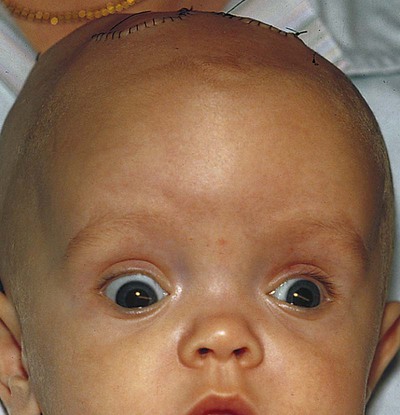

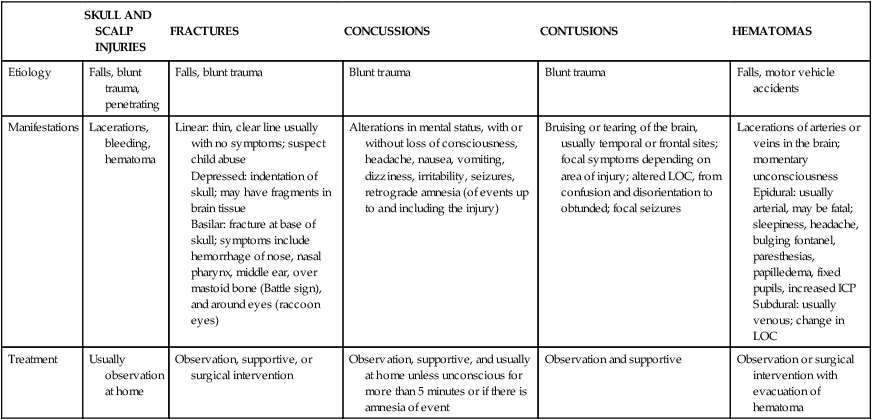

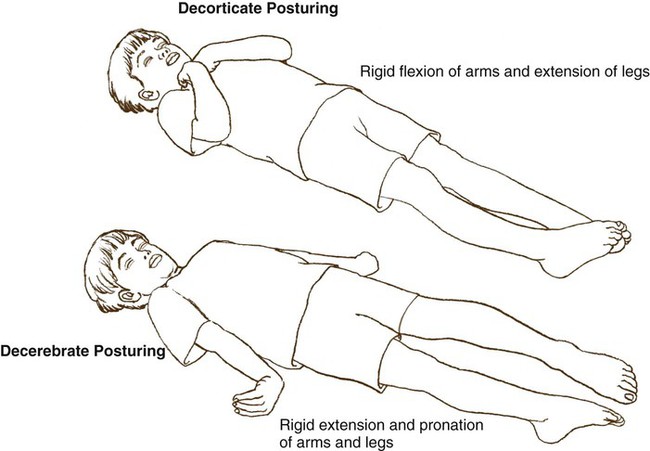

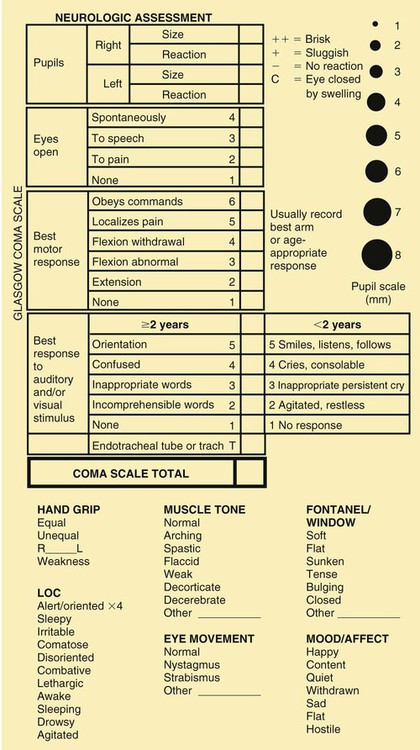

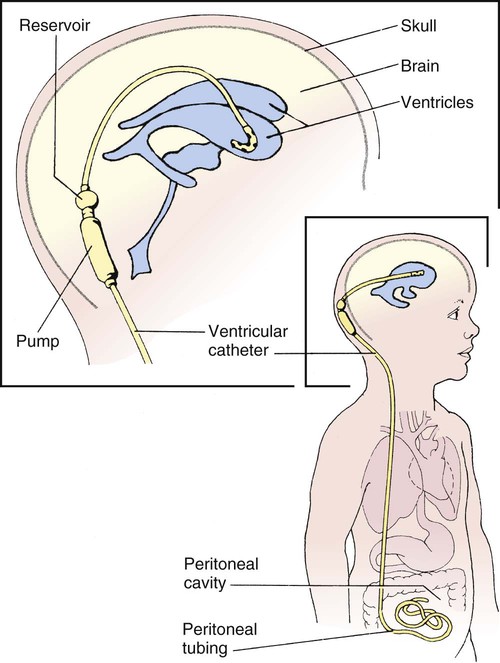

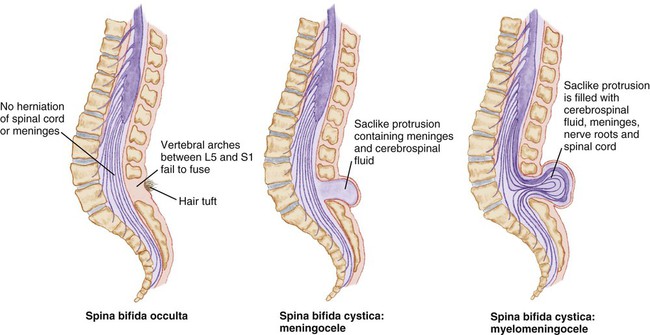

1. Define the vocabulary terms listed 2. List the differences found in the neurologic system of a child 3. Describe the signs of increased intracranial pressure in a child with a head injury, including nursing observations necessary to establish a baseline of information 4. Discuss care of the child with intracranial hemorrhage 5. Discuss use of the pediatric coma scale 6. Differentiate between communicating and noncommunicating hydrocephalus 7. Outline the pre- and postoperative nursing care of a neonate with spina bifida cystica 8. Explain how to care for a child with bacterial meningitis or viral encephalitis 9. Differentiate the types of generalized and partial seizures 10. Describe the nursing measures necessary for a child during and after a tonic-clonic seizure 11. Discuss care of the near-drowning victim 12. Differentiate two types of hearing loss The nervous system grows rapidly before birth and well into the first year of life. It will slow to a more gradual rate in later childhood. Brain growth is measured with head circumference and plotted during the first 3 years of life. There is an increased cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in childhood that is almost twice that of adults (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2007). This is due to the increased metabolic requirement in early childhood. Myelinization of the nerves in the CNS progresses in a head-to-toe (cephalocaudal) and proximodistal sequence. This myelinization and maturation of the nervous system will lead to the development of motor skills in the growth and development process. Brain development will be influenced by environmental stimuli. Box 13-1 reviews additional physical differences. Intracranial hemorrhage, a common birth injury, may result from trauma or anoxia. It occurs more frequently in the preterm infant, in whom the blood vessels are fragile. Blood vessels within the skull are broken, and bleeding occurs into the brain. When the diagnosis is made, the specific location of the hemorrhage should be noted: subdural or subarachnoid, epidural or intraventricular (IVH is discussed in Chapter 5). This injury may also occur during precipitated delivery, prolonged labor, or when the newborn’s head is large in comparison with the mother’s pelvis. Infants and children suffer from head injuries that may occasionally result in brain damage. Falls, shaken baby syndrome, motor vehicle injuries, and bicycle injuries account for a large number of these statistics. Toddlers especially are famous for the number of blows received to the head. Fortunately, most of these injuries are not serious, but they are alarming to parents. The skulls of infants and young toddlers are more pliable and absorb much of the impact to the head. By 2 years of age, both fontanels have completely closed, and the cranium no longer has the same pliability in response to force. Types of head injuries are discussed in Table 13-1. Table 13-1 Frequently a child who has had a blow to the head is brought to the hospital for observation to rule out or confirm the diagnosis. Initial care of the child with a head injury includes assessment of the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation), assessment for spinal cord injury, and documentation of baseline vital signs. The child may have all or some of the following symptoms: headache (manifested by fussiness in the toddler), drowsiness, blurred vision, vomiting, and dyspnea (see Did You Know?). In severe cases, the child may be completely unconscious or having seizures. Decerebrate (indicating injury to the midbrain) or decorticate (indicating injury to the cerebral cortex) posturing may be evident (Figure 13-1). A careful history is obtained to determine any preexisting conditions and to ascertain the exact circumstances of the accident. Of particular importance is the child’s state of consciousness immediately after the occurrence. Radiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to diagnose the specific head injury. Should the child be alert, without significant symptoms, and the parents reliable, the child can be sent home with instructions for observation. The Pediatric Coma Scale (Figure 13-2), based on the adult Glasgow Coma Scale, is valuable in determining various LOCs. It consists of three parts: eye opening, motor response, and verbal response. A numerical value is assigned to each part. The lower the score, the deeper the coma. Signs and symptoms depend on the time of onset and the severity of the imbalance. The classic sign both in congenital hydrocephalus and in hydrocephalus with onset in infancy is an increase in head size (Figure 13-3). The direction of skull expansion depends on the site of obstruction. Transillumination (trans, across; illuminare, to enlighten), or the inspection of a cavity or organ by passing a light through its walls, is an older diagnostic procedure used to visualize fluid. (This method uses a flashlight with a sponge rubber collar held tightly against the infant’s head in a dark room to indicate areas of increased luminosity.) Another sign is a bulging anterior fontanel and separation of cranial sutures. The scalp is also shiny and the veins dilated. The infant appears helpless and lethargic. The body becomes thin, and the muscle tone of the extremities is often poor. In addition to the infant’s shrill and high-pitched cry, irritability, vomiting, and anorexia are present. Convulsions may also occur. In severe infantile hydrocephalus, the eyes may appear deviated downward, which is known as the “setting sun” sign (Figure 13-4). Children with an onset of hydrocephalus later in childhood may have minimal enlargement of the head and display the signs and symptoms of increased ICP. Treatment is directed toward relief of symptoms, treatment of the underlying problem (such as a tumor), and treatment of complications. If there is an obstruction, such as a tumor, it may be removed surgically. In other conditions, a shunt is placed by inserting special tubing that provides drainage of the CFS from the ventricles to another area of the body, where it is absorbed and eventually excreted. Two types of shunts are used: the ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt and the ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt. The VP shunt is the most commonly used (Figure 13-5). New shunt systems now allow for growth and have generally eliminated the necessity for shunt revisions. (Shunts still need to be replaced if a malfunction occurs). Shunts work with a one-way valve that opens at a predetermined intraventricular pressure and closes when the pressure falls below that level. This prevents CSF from flowing back upward. Nurses and parents may be taught how to pump the shunt. Spina bifida cystica consists of the development of a cystic mass in the midline of the spine (Figure 13-6). Meningocele and meningomyelocele (also called myelomeningocele) are two types of spina bifida cystica. A meningocele (meningo, membrane; cele, tumor) contains portions of the membranes and CSF. The size varies from that of a walnut to that of the head of a newborn infant.

Neurologic and Sensory Disorders

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Price/pediatric/

![]() The Nervous System

The Nervous System

Neurologic Disorders

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Head Injuries

SKULL AND SCALP INJURIES

FRACTURES

CONCUSSIONS

CONTUSIONS

HEMATOMAS

Etiology

Falls, blunt trauma, penetrating

Falls, blunt trauma

Blunt trauma

Blunt trauma

Falls, motor vehicle accidents

Manifestations

Lacerations, bleeding, hematoma

Linear: thin, clear line usually with no symptoms; suspect child abuse

Depressed: indentation of skull; may have fragments in brain tissue

Basilar: fracture at base of skull; symptoms include hemorrhage of nose, nasal pharynx, middle ear, over mastoid bone (Battle sign), and around eyes (raccoon eyes)

Alterations in mental status, with or without loss of consciousness, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, irritability, seizures, retrograde amnesia (of events up to and including the injury)

Bruising or tearing of the brain, usually temporal or frontal sites; focal symptoms depending on area of injury; altered LOC, from confusion and disorientation to obtunded; focal seizures

Lacerations of arteries or veins in the brain; momentary unconsciousness

Epidural: usually arterial, may be fatal; sleepiness, headache, bulging fontanel, paresthesias, papilledema, fixed pupils, increased ICP

Subdural: usually venous; change in LOC

Treatment

Usually observation at home

Observation, supportive, or surgical intervention

Observation, supportive, and usually at home unless unconscious for more than 5 minutes or if there is amnesia of event

Observation and supportive

Observation or surgical intervention with evacuation of hematoma

Treatment and Nursing Care

Hydrocephalus

Signs and Symptoms

Diagnosis and Treatment

Myelodysplasia/Spina Bifida

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

times.

times.