Chapter 4 Assessment and Diagnosis

A comprehensive assessment of the patient who presents for psychotherapy is necessary to develop an appropriate treatment plan. Chapter 3 provides guidelines for the initial session when the advanced practice psychiatric nurse (APPN) can assess the person over a number of sessions. In some settings, however, a comprehensive assessment must be conducted during the initial session. This chapter presents the format and tools for such an assessment. The comprehensive psychiatric database and instruments included in this chapter also can be integrated in a setting that allows the therapist to conduct an assessment over several sessions. The therapist may bill for an initial, comprehensive assessment only once during the course of the assessment process. In reality, most assessments continue throughout the treatment, and therapists initially use only selected instruments in acquiring a database. The setting and population with whom a therapist works determine what is necessary and what is optional. There may be other screening tools not included in this chapter that are required by the agency or employer.

Even if the APPN sees the person only for the assessment, a sensitively crafted intake assessment can be a powerful therapeutic tool. It can establish rapport between patient and therapist, further the therapeutic alliance, alleviate anxiety, provide reassurance, and facilitate the flow of information necessary for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan (or not). For better or for worse, an assessment is a relational process. It represents a verbal and nonverbal dialogue between two therapeutic partners, whose behaviors reciprocally influence each other’s style of communication and result in a specific pattern of interaction (Shea, 1998). To the degree this pattern of interaction transcends its question-and-answer format to constitute an authentic encounter between the patient and therapist, an assessment can play a significant role in the change process (Safran & Muran, 2000). At the very least, a sensitively crafted assessment can help ensure that a patient in crisis or distress returns for follow-up care.

Shea (1998) identifies the broad goals of clinical assessment as follows:

1. To effectively engage the patient in the data-gathering process

2. To collect information and form a valid database

3. To develop an evolving and compassionate understanding of the patient

4. To develop an assessment from which a differential diagnosis can be made

5. To use the diagnosis as a guide to the choice of an appropriate treatment plan

6. To effect some decrease in the patient’s anxiety

7. To instill hope and ensure that the patient will return for the next appointment

The goals of engaging the patient in a therapeutic alliance, data gathering, uniquely understanding the person who presents as a patient, and arriving at the most appropriate diagnosis and treatment plan are parallel assessment processes (Shea, 1998). Generally, the more powerfully engaged the patient and therapist are during the assessment process, the more valid are the data on which to base the diagnosis that will guide the choice of treatment plan.

In a clinical sense, validity refers to the accuracy of the database (i.e., whether the clinician is eliciting the information s/he is trying to elicit) (Shea, 1998). The more valid the database—and by implication, the more valid the diagnosis—the more confidence the therapist can have in the treatment plan and the more reassuring s/he can be in parlaying information to patients about their probable course or expected outcomes. The successful engagement of patients in the assessment process—which requires empathy, patience, a willingness to afford patients sufficient time to tell their stories in their own manner, the ability to structure patients when necessary, and careful attention to patients’ needs for comfort, privacy, and security—is key to the validity of assessment data. Consequently, this chapter examines important areas for assessment, providing specific screening tools to aid in the assessment process and attending to the manner in which the therapist fosters the therapeutic alliance. It describes the process of taking a history and the comprehensive assessment of areas of patient functioning important to the practice of psychotherapy, including ego functioning, affective development, interpersonal relationships, and belief systems. The chapter ends with a discussion of diagnosis and case formulation, without which the treatment plan has no rationale.

Taking a History

Fundamentally, the psychiatric history is a kind of life story told to the therapist by a patient in his/her own words and from his/her own point of view (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). In some situations and with the patient’s consent (excluding only emergency situations), the history may include information from other sources, such as a referral source, parent, spouse, former therapist, or medical record. The therapist must collaborate with a consenting patient in negotiating the details of how and when to obtain collateral information from other sources. A comprehensive history includes information about the current illness (i.e., factual data related to the onset and chronology of current symptoms) and the past and present psychiatric and medical history. It includes a psychiatric review of systems, a medication history, a history of substance use and abuse, a history of violence or self-destructive behavior, trauma history, and developmental, family, social, educational, occupational, and legal histories. Box 4-1 provides an outline of the major sections, or clinical domains, of the psychiatric history as adapted from the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guidelines for Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults (APA, 1995) (Box 4-2) and Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Appendix I-11 (p. 150) outlines the content of a comprehensive psychiatric database developed from multiple sources, including my professional experiences in various clinical assessment venues (APA, 1995; Gordon & Goroll, 2003; Marken et al., 2005; Morrison, 1995; Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Scully, 2001; Shea, 1998). Appendix I-12 (p. 156) presents a sample intake assessment form adapted from Shea (1998) that includes all sections of the comprehensive psychiatric database.

Box 4-1 Major Sections of the Psychiatric History

Adapted from APA (1995). Practice guideline for psychiatric evaluation of adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(11S), 67–80; Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (2003). Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Obtaining such a comprehensive history from the patient and, if necessary, from informed sources close to the patient is essential to making an accurate, culturally appropriate diagnosis and developing a specific, culturally sensitive, and effective treatment plan (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). From this life story, the therapist can begin to paint a picture of the patient’s personality characteristics, strengths, areas for growth, interpersonal style, cultural context, and development from her/his earliest years to the present moment. Taking a history—this co-creative act of constructing a comprehensive life story—allows the therapist and ultimately the patient to more completely understand who the patient is, where the patient has come from, and where the patient may go in the future (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). It is an essential first step to rewriting that story. The fact that persons in psychotherapy come to change their life stories over the course of treatment is a positive development, because patients reflections on their past conditions in light of the changing present heralds the creation of a different future (Barker, 2001). The revision of life stories through narrative is the essential work of psychotherapy, which is a unique form of encapsulated experience that focuses on the life experiences of another such that the experiences can be reconsidered, reevaluated, understood, and in so doing, reconstructed (O’Toole & Welt, 1989, p. 99). It all starts with taking a history.

Opening Moves

Practically speaking, how does the therapist take a comprehensive history in one session? In the first moments of an initial assessment in those settings where this is necessary, the therapist must accomplish a number of important alliance-building tasks, including an appropriate greeting, introductions (if not already made in an earlier contact), an indication of seating preference, a brief introduction to the assessment process, and an open-ended invitation to the patient to tell the therapist how s/he can be of assistance. In these moments, the therapist should indicate what the interview will be like, how much time it will take, what sort of questions will be asked, and what sort of information the patient is expected to share. The therapist needs to create a comfortable and secure environment that allows the patient as much control as possible (Morrison, 1995). Early in the assessment, a nondirective interview style with open-ended questions yields control to the patient, generally builds rapport, and garners facts that are more reliable (Morrison, 1995; Shea, 1998). As Morrison (1995) states, “Studies have shown that [clients] give the most valid information when they are allowed to answer freely, in their own words, and as completely as they wish. So, whenever possible, phrase … questions in an open-ended way that allows the widest possible scope of response” (p. 49). To illustrate how a therapist may begin the data-gathering process, Box 4-3 summarizes the first moments of an initial clinical assessment with a fictive psychotherapy patient, who has indicated in an earlier phone contact her preference to be called by her first name.

Box 4-3 Beginning the Clinical Assessment

Therapist:Hello, Beth. It’s nice to meet you in person. Please, sit down. You can make yourself comfortable here. [Points to a chair.]

Therapist: As I mentioned on the phone, I am an advanced practice psychiatric nurse, and in today’s session, I hope to get a clearer sense of the difficulties you alluded to on the phone. I will be asking questions about important areas of your life, and with your permission, I would like to be able to take a few notes. I don’t want to forget anything. [Smiles, waits for a response.]

Therapist: I would like to get as much history as I can today, but if we aren’t able to get to everything, we’ll continue next week. I’ll be asking lots of questions about your present circumstances and your past history, so if any of my questions make you uncomfortable, please let me know. I do not want to contribute to your distress, but I do want to hear as much about your thoughts and feelings as you are comfortable telling me.

Patient: That’s fair. I’ll try.

Therapist: Could you tell me in whatever way you like what brings you in today?

Patient: [Takes 5 to 10 minutes to tell her story, with open-ended prompts by the therapist only as needed (e.g., “What happened then?” “Could you tell me more about that?” “How were you feeling at that time?” “What else was going on?”]

In the medical model, the patient’s response to the therapist’s opening question is called the chief complaint, but it might better be called the patient-identified problem in a holistic nursing model. It is the patient’s stated reason for seeking help and is recorded verbatim. It often reveals the problem uppermost in the patient’s mind (Morrison, 1995) and can indicate the content region (Shea, 1998) or clinical domain (APA, 1995) the therapist should explore first. When the patient’s response to the therapist’s opening question is a denial that anything is wrong, it is often helpful to rephrase the question in terms of why others may think the patient should seek help, such as “Can you tell me what went on that your _____ (e.g., mother, spouse, employer, primary care provider, court officer) thought you might benefit from coming in?” Another technique is to ally with the patient’s resistance or side-step it (e.g., “It may be that nothing is wrong, but because you’re already here, maybe we can try to figure out if there is something else I can help with.”). Such denials are the first indication that the therapist may encounter significant resistance by the patient to engaging in psychotherapy, and they are cogent reminders that the first task of data gathering is alliance building.

During the minutes that follow the patient-identified problem, while the patient is freely telling her/his story, much is signaled that the therapist will need to explore in greater depth later in the interview. The therapist needs to mentally note or write down these areas of clinical interest (i.e., clinical domains or content regions) so that specific questions can be asked at the appropriate time. Box 4-4 summarizes the content from Beth’s response to the therapist’s opening question.

Box 4-4 Exploring the Patient-Identified Problem

Therapist: Can you tell me in whatever way you like what brings you in today?

Patient: I don’t know. [Long pause.] Donna N. [referral source] sent me. She and my mom and my adviser thought I had depression. Actually, I’ve been depressed on and off since the 10th grade. [Another long pause.] I have a lot of problems getting along with my parents, especially my mom. I’ve been thinking about dropping out of school until spring semester to get my head together, but my adviser talked me out of it. I am dropping only one class. I’m not really happy about deciding to stay in school. I cried for 3 hours about it. I’m overwhelmed with school. I can’t catch up. I don’t care about anything anymore. I’m happy just to stay in bed. The slightest things make me feel bad. I’m angry all the time. My mother thinks my personality has changed. I don’t know. Maybe it has. I’m more irritable around my boyfriend. The slightest things he does put me on edge. My mother, too. She calls me every night in the middle of studying, and it gets on my nerves. If she didn’t call me. I wouldn’t even think about her.

Therapist: Beth, you mentioned you are quite irritable these days and have been crying a lot. Can you tell me more about the depressive symptoms you’ve been having?

Patient: Well, I sleep okay, but I wake up tired, and I have no energy for anything. I’m not really sad, just angry and irritable and overwhelmed with everything.

Patient: A few days ago I thought about suicide. It just crossed my mind. I don’t really want to die. I just want my problems to end.

Therapist: What did you think about? [Therapist takes this opportunity to thoroughly assess current suicide risk and to explore the past history of suicidal behavior. She then returns to the “depression” content region to more thoroughly assess the possibility of a diagnosable mood disorder, such as major depression or dysthymia.]

Expanding the Assessment

Although there are no rules about which content region to explore first or in what order to address them, it is generally advisable to thoroughly explore one before moving on to another (Shea, 1998). In this example, the therapist chooses to first explore the symptoms of a possible mood disorder and, when the patient broaches the subject, to assess Beth’s current suicide risk. However, she makes a mental note to follow these content regions with the developmental, family, and social histories, focusing on Beth’s strained relationships with her mother and boyfriend and on her academic decline. After a thorough assessment of the current suicide risk and any history of suicidal behavior, the therapist returns to the depression content region (i.e., history of the present illness [HPI]) to get a more thorough sense of the onset, extent, and chronology of mood symptoms. In so doing, she learns more about Beth’s hostile and enmeshed relationship with her mother. It seems the patient has been dysthymic since the 10th grade, when Beth’s mother put her daughter’s dog to sleep without her knowledge. This occurred on the day Beth got her braces removed from her teeth. A family celebration had been planned: “It was supposed to be a happy day for me. It wasn’t.” Apart from the fact it is the humane thing to do, an engaged clinician should take this opportunity to further strengthen the therapeutic alliance—which facilitates continued data gathering—by empathizing with the patient’s distress about what appears to have been a significant loss and a rather cruel act of sabotage by the patient’s mother (e.g., “You must have been very hurt by this.”). The therapist then needs to move to the developmental and family history to learn more about this incident and to more thoroughly assess the family dynamics, especially the patient’s relationship with her mother (e.g., “Tell me more about that day, your relationship with your mother, and your family situation.”).

In this way, the therapist proceeds to take a history, thoroughly exploring all the major sections of the comprehensive psychiatric database (see Box 4-1) by opening new content regions as opportunities arise. Open-ended questions invite exploration in new content regions, reveal what is uppermost in a patient’s mind, and may yield important information about the patient’s capacities, defenses, or degree of resistance to engaging in psychotherapy. Closed-ended questions elicit the specific details, such as symptom type, severity, frequency, and duration and the context in which a symptom occurs, that are necessary to assess a new clinical area. Table 4-1 provides an outline of open-ended and closed-ended assessment questions along a continuum of openness. Opportunities to open new content regions do not always arise spontaneously, and in those cases, the therapist must guide the assessment into new clinical areas. Occasionally, time constraints may dictate that the therapist makes an abrupt transition to unexplored content regions to obtain a thorough assessment within the allotted timeframe. However, it can be done skillfully, sensitively, and in a manner that continues to facilitate the therapeutic alliance. Box 4-5 illustrates the use of open-ended and closed-ended questions to facilitate skillful, even if abrupt, transitions to new content regions.

Table 4-1 Assessment Questions: Continuum of Openness

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Open-Ended Types: | |

| Open-ended questions | What brings you in today? |

| How can I help you? | |

| How would you describe your relationship with …? | |

| Gentle commands | Tell me about your family situation. |

| Try to describe how you felt when. … | |

| Share with me what you think a good outcome would be. | |

| Intermediate Types: | |

| Swing questions (i.e., patient can say “no” or patient can elaborate) | Can you describe the depressive symptoms? |

| Can you tell me anything more about that? | |

| Can you tell me what you’re thinking right now? | |

| Qualitative questions | How have you been sleeping? |

| How is school going? | |

| How have you been getting along with your mom? | |

| Statements of inquiry | So you have never before received any therapy? |

| Your mother decided to go back to school when you did? | |

| You say you just want to stay in bed all the time? | |

| Empathic statements | You must have been so hurt by that. |

| That is very frustrating. | |

| It is hard to lose someone you love. | |

| Facilitating statements | Go on. |

| I see. | |

| Closed-Ended Types: | |

| Closed-ended questions | How many drinks did you have? |

| How often do you feel that way? | |

| Closed-ended statements | You can sit down here. |

| We will take about 50 minutes to __. | |

| Medications can be very effective in these cases. | |

Adapted from Shea, S. C. (1998). Psychiatric interviewing: The art of understanding (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Box 4-5 Transitioning to New Content Regions

Therapist: Beth, you’ve told me a great deal of very helpful information about your family situation. I’m beginning to understand the kinds of things you’re dealing with. But I’ve noticed the clock, and we have only 15 minutes left. There are some other things I need to know before we can talk about where to go from here. Can you handle a few more questions? [Closed-ended question.]

[Note: Using a patient’s name judiciously can comfort, contain, invite closeness, and facilitate the therapeutic alliance. If used artificially or too often, it can seem ingratiating or insincere and can distance the patient and impede the therapeutic alliance.]

Therapist: You mentioned that you saw a school counselor when you were in the 10th grade and your dog was put to sleep. Can you tell me more about that treatment? [Open-ended, swing question.]

Patient: Well, there’s not much to tell. I saw her only once. It wasn’t really a treatment. We talked for about 30 minutes. A teacher was concerned when she saw me crying at school. I didn’t go back. She said I didn’t have to if I didn’t want to.

Therapist: Were there any other times that you saw a counselor, therapist, or psychiatrist? [Closed-ended question.]

Therapist: So you’ve never before received any therapy or any psychiatric treatment, either as an inpatient or outpatient? [Closed-ended statement of inquiry.]

Therapist: Okay. What about substance abuse? [Open-ended question.]

Patient: Treatment? No, never. In fact, I don’t use anything. I don’t even drink coffee. I suppose … [Long pause; therapist waits.]

Therapist: Go on. [Facilitating statement.]

Patient: Well, I have tried some things, but it was a long time ago.

Organizing the History of the Present Illness

Of all the major content regions of the psychiatric history, the most important is the HPI. It represents the heart of the assessment interview. It is the most substantial part of the initial clinical assessment and includes a description of the patient’s key symptoms, their timing and associated problems, and the stressors that account for their exacerbation. When well organized, the HPI develops much like a mystery short story (Kluck, n.d.). It outlines the onset of the patient’s key symptoms and progresses chronologically until the time of the patient’s presentation for evaluation. By the end of the HPI, an experienced clinician should be able to read the written assessment and construct a near-complete differential diagnosis. A thorough and well-constructed HPI contains the following components, roughly in the following order:

1. A statement of the patient’s baseline functioning or last period of stability

2. Any previous diagnoses of psychiatric disorder and a brief synopsis of the course and treatment

3. The onset of the first symptom and its precipitant

4. A chronology of one to three key symptoms, including when they worsened and the precipitant events that caused them to worsen

5. Associated symptoms related to the one to three key symptoms

6. Documentation of the “why now” (i.e., why the patient presents for treatment now)

7. Repetition of components 3, 4, and 5 if there is more than one diagnosable disorder

8. A list of pertinent negative symptoms (i.e., symptoms that are not present)

9. A list of additional stressors not mentioned (Kluck, n.d.).

Box 4-6 documents the HPI in the case of Beth, inserting numbers 1 through 9 at appropriate points in the text to mark the essential HPI components listed previously.

Box 4-6 Documenting the History of Present Illness

Beth is a 20-year-old college junior majoring in business administration who has felt chronically depressed since approximately the 10th grade, when her mother put her dog to sleep without her knowledge on a day the family planned to celebrate the removal of her braces (1).* She has no previous history of psychiatric treatment (2). In August, she moved away from home for the first time after having an argument with her parents about money and college expenses. The focus of the conflict was Beth’s resentment about their refusal to help her more with college expenses when they had money for new recreational vehicles, house remodeling, and most significantly, her mother’s sudden enrollment in the Denton Business University (coincident with Beth’s change of majors from psychology to business administration). She moved in with her boyfriend of the last year and a half and found herself feeling increasingly irritated with him (3). Despite these stressors and her increasingly low mood, she functioned relatively well in school until approximately 3 weeks ago, when she began to feel more depressed, apathetic, and fatigued than usual. She wanted to drop out of school but was talked out of it by her academic advisor and ended up dropping only one course. She states she sleeps well but wakes up tired and has no energy. She “doesn’t care about anything anymore” and is “happy to stay in bed.” The “slightest things make her feel bad,” and she has crying episodes three or four times per week. She has lost approximately 8 pounds in the past 3 weeks. She reports that she does not feel sad, hopeless, or helpless, just overwhelmed by school, work, changing majors, having to interact with her parents (her mother calls her every evening during her study time), and having to work harder to get along with her boyfriend in close quarters. All her symptoms have worsened over the past 1 to 2 weeks and are exacerbated by the seemingly daily conflict with her mother and boyfriend (4). Within the past week, she has begun scratching on her wrists with plastic, serrated knives—something she has not done since high school (5). Three days ago, a particularly loud and hostile phone conversation with her mother annoyed Beth’s boyfriend, causing a bitter argument between the two of them. He stomped out of the apartment and did not return that night (6). She felt “abandoned” and “panicky,” and thoughts of suicide (without plan or intent) crossed her mind, which scared her enough that she contacted her college vocational counselor, who referred her for psychiatric evaluation (7). She denies acute suicide ideation today, as well as any symptoms of mania or hypomania, psychosis, or severe anxiety (8). Additional stressors include 20 to 25 hours per week of work at McDonald’s while carrying 12 semester credits, a substantial tuition bill that comes due very soon, and a growing sense that she needs to move again because she cannot tolerate the increased closeness with her boyfriend (9).

*Parenthetic numbers 1 through 9 mark the essential components of the history of present illness that are listed in the text.

Mental Status Examination: To Do or Not To Do

The mental status examination (MSE) has become a standard component of the initial clinical assessment. It is the clinician’s description of the patient’s mental functioning. It is a direct examination of the patient’s behavior and the examiner’s inferences from what the patient says and does. In making these inferences, the clinician must carefully consider the patient’s educational and cultural background (Giese, n.d.). Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss in detail how to perform a formal MSE, Appendix I-11 includes a comprehensive outline of the content and possible organization of a formal MSE. Many of its sources (see Appendix I-11, p. 150) describe the performance of the MSE in great detail.

All APPNs must learn to perform a comprehensive, formal MSE, and there is value in performing one even in the case of psychotherapy patients who present as cognitively intact. Although the volume of material to cover can seem daunting, much of the MSE is obtained during the general history-taking interview, requires no special questions or tests, and can be assessed through informal observation that begins the moment the therapist first encounters the patient. The key is to know what elements to look for and to be systematic in looking for them. When comfortable with a format for a complete MSE, the therapist can tactfully transition from informal observation to a direct, systematic examination of the patient’s cognitive status when a suitable opportunity presents itself (Box 4-7).

Box 4-7 Transitioning to the Mental Status Examination

Therapist: You mentioned a short while ago that you’re having trouble with your memory, so let’s see exactly what that difficulty is. Can you tell me today’s date?

Therapist: You say that you cannot concentrate. Let’s take a closer look at that. I’m going to give you three things to remember and then ask you in a few minutes to recall them: a red ball, 37 Elm Street, and a clock radio. Can you repeat them now?

Sometimes, opportunities for a smooth transition to the formal MSE do not present themselves. Occasionally, a complete examination is impossible, such as with a very agitated or uncommunicative patient, and sometimes, it can seem insulting to ask apparently high-functioning people what today’s date is or whether they can remember a “red ball” and “37 Elm Street.” Nevertheless, when a clinician inadvertently fails to perform a formal MSE or makes a deliberate decision not to perform an MSE in a patient who seems unimpaired, the therapist risks missing important information that may emerge only through a direct, systematic examination of a patient’s cognitive function. “Your best bet is to choose a format, memorize it, and perform your mental status exam the same way every time until it has become second nature” (Morrison, 1995, p. 105).

Box 4-8 presents one way of organizing the data from a MSE. It summarizes the results of Beth’s formal MSE as it might appear in a formal diagnostic report or on a clinical assessment summary. However, therapists must develop their own systematic method of obtaining, organizing, and recording the MSE, so the process becomes second nature. Although Beth’s MSE result is essentially within normal limits, there is value in recording specific examples of mental status abnormalities.

Box 4-8 Documenting the Mental Status Examination

Beth is an attractive, subdued, casually and appropriately dressed, 20-year-old SWF who appears to be her stated age. She is quite distressed and seems to be fighting back tears. However, she makes good eye contact and readily engages with the examiner. Her speech is fluent, soft, and quavering; her affect ranges from flat to sad and angry. Her mood is dysthymic and congruent with her affect. Her movements are graceful and without abnormality. She is alert, is fully oriented, and evidences no problems with attention, concentration or memory. She can recall 6/6 objects at 0 and 5 minutes, can do serial sevens without difficulty, repeats five digits forward and backward, can abstract proverbs, and has an adequate fund of general knowledge. Her thought processes are logical, linear, and goal directed. Prominent themes in her thought content include her smoldering resentment toward her parents, particularly her mother, and her feelings of being overwhelmed by her schoolwork. There is no evidence of thought disorganization. She denies current, active suicide or homicide ideation, as well as all signs and symptoms of psychosis. Superficially, her judgment is intact. She appears to be of above-average intelligence; however, her problem-solving abilities are transiently overwhelmed. She is excessively worried about “not being ahead of the game,” as she would customarily be.

Timeframes and Closing Moves

The patient’s unique circumstances determine how much time the therapist spends on each major section of the psychiatric history. In Beth’s case, the therapist will spend much of her time gathering data for the HPI and the family, developmental, and social histories. Very little time is needed for the psychiatric history, medical history, substance use history, and MSE, because the patient is young, physically healthy, cognitively intact, and has no history of prior psychiatric treatment or significant substance use. Although the needs of the patient determine which content regions are most appropriate for deeper exploration (taking into consideration time constraints, usually 50 to 60 minutes for an initial assessment), Morrison (1995) and Shea (1998) provide guidance on how to carve up the allotted time if the assessment data must be gathered in one session. Morrison (1995, p. 9) suggests the following:

15%: Chief complaint and free speech

30%:HPI; pursuit of information relevant to the differential diagnosis; histories of suicide, violence, or substance use

15%: Medical history; review of systems; family history

25%: Personal (developmental and social) history

5%: Discussion of the diagnosis and treatment plan; plan for next visit

Shea (1998) suggests at least 7 to 8 minutes for the “scouting” period, which is what Morrison (1995) calls free speech and what is essentially the time it takes for the patient to narrate his/her story. By the end of the first 30 minutes of the initial assessment, the therapist should be nearing the completion of the content regions that seem most pertinent for that patient. Often, during the third 15-minute period, the family history, medical history, social history, and the formal MSE are completed (Shea, 1998). In Beth’s case, exploration of the family, developmental, and social issues would have been explored in depth earlier, because they are uniquely important content regions for her and might have extended into the third 15-minute assessment period. In any case, Shea (1998) recommends that the therapist monitor, at least every 5 to 10 minutes, the progress of his/her data gathering and adjust the pace as necessary. It is probably a good idea to check with the patient by asking, “Is this okay for you?” During the last 15 minutes of the assessment period, regional content explorations of the major sections of the psychiatric history are completed; final points of clarification are pursued; and termination occurs. Time can get away from even experienced psychotherapists, especially when a patient is particularly distressed, verbose, or disorganized. However, whenever possible, the last 5 to 10 minutes of the assessment period should be devoted to discussing the diagnosis, treatment recommendations, and follow-up plan; answering whatever questions the patient may have about those findings; processing the patient’s assessment experience; paving the way for the next visit; and in doing all that, continuing to build the strong therapeutic alliance on which a good psychotherapy outcome depends. Box 4-9 illustrates the closing minutes of Beth’s initial clinical assessment.

Box 4-9 Ending the Clinical Assessment

Therapist: [Summarizes diagnostic impression and treatment recommendations.] So that’s what I’m thinking right now. What are your thoughts?

Patient: What happens if the medication doesn’t help?

Therapist: We have lots of options, including trying a different medication, but it is important to remember that medication is only one tool at our disposal. Even when it works, it doesn’t solve relationship problems, although it can give you more energy to deal with them. That’s why psychotherapy is so important. Do you have thoughts about that?

Patient: Not really, except … [long pause; therapist waits] I don’t really like talking about my family. It leaves me with a bad feeling.

Therapist: Yes, I have a pretty clear sense of how difficult that was for you. Is there anything I could have done differently to make that easier for you?

Patient: No, I don’t think so.

Therapist: Tell me more about what this [assessment] experience has been like for you?

Patient: Actually, it wasn’t as bad as I was thinking it would be. In a way, I feel relieved. I’m willing to try anything.

Therapist: I can hear how distressed you’ve been. On the other hand, that’s a very positive attitude. I think there is every reason to believe you can feel significantly better very soon. And if not, we will work together to figure out why. How does that sound?

Therapist: Will this time next week work for you? [Details of follow-up are negotiated.]

Assessing Ego Functioning

The assessment of ego functioning from the perspective of ego strength (as opposed to ego deficit) is a valuable skill for nurse psychotherapists. The identification and assessment of ego strength helps the therapist locate a patient on a developmental continuum, suggests a place to join with the patient to begin the therapeutic work, provides data to develop therapeutic goals, and creates a valid construct for psychotherapy outcome measurement (Bjorklund, 2000; Burns, 1991). The person who gains ego strength as a result of his/her work with a therapist has made noteworthy therapeutic progress. Broadly defined, ego strength is the capacity for effective personal functioning (Burns, 1991). It encompasses specific capacities such as adaptability, resourcefulness, self-efficacy, self-esteem, interpersonal effectiveness, life satisfaction, and the many other mental health indicators succinctly encapsulated in Freud’s (1961) well-known phrase “to love and to work.” Like the solid foundation of a well-built house, ego strength supports the individual in the pursuit of life goals, dreams, and ambitions, especially during times of trouble. It ensures coping abilities, provides an individual with a sense of identity, can be recognized during initial assessment and throughout therapy, and increases as patients grow in maturity (Bjorklund, 2000). To the degree each ego function can be identified and assessed in the clinical situation, ego strength can be acknowledged, rated, reinforced, supported, built on, or “loaned” to some degree to lower-functioning patients by their relatively higher-functioning therapists in the process of identifying with the therapist’s own ego strength (Bjorklund, 2000).

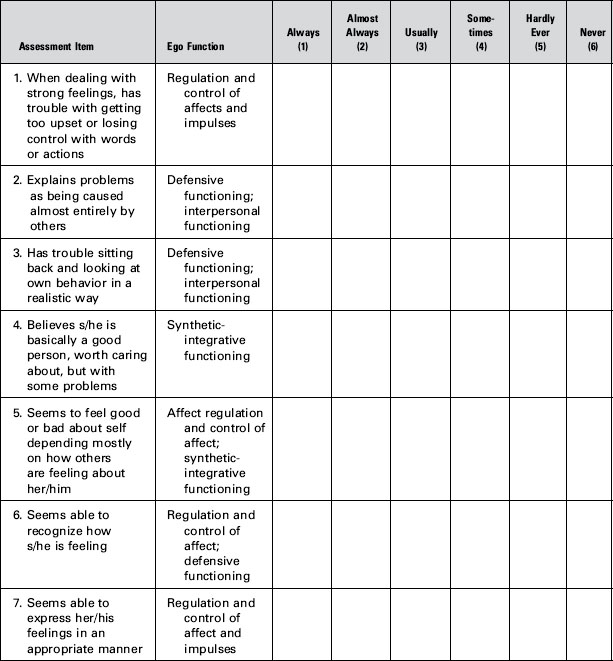

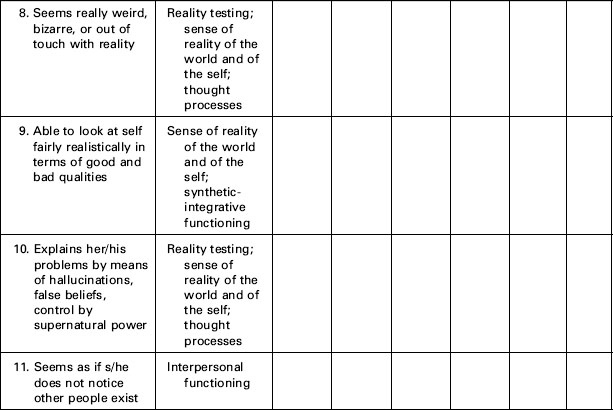

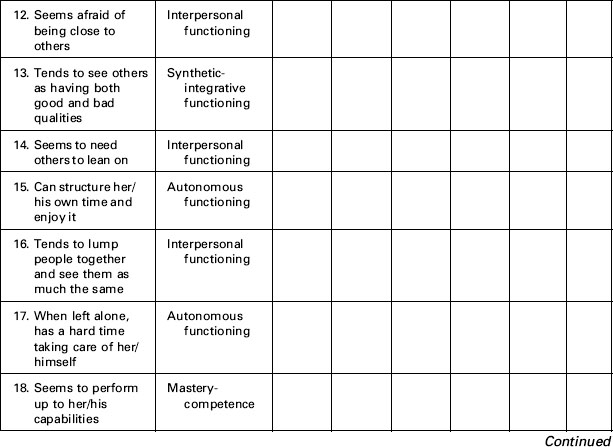

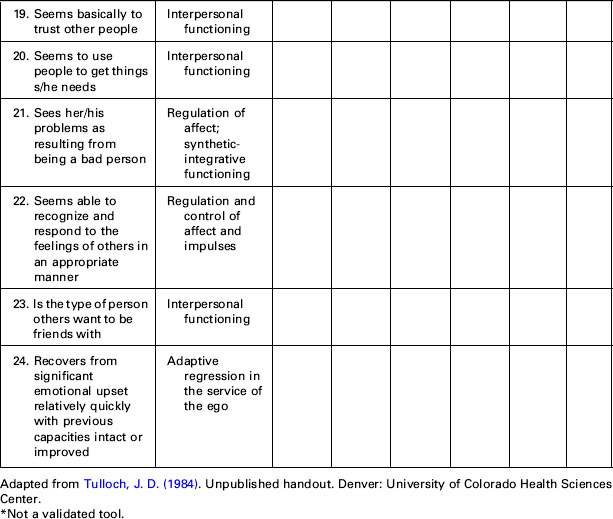

Identification occurs through the ongoing corrective emotional experience that constitutes therapy and the therapist’s repetitive modeling of the kinds of coping behaviors indicative of ego strength. Table 4-2 identifies 12 ego functions and their definitions (Bellak, 1989). The list can be used as an assessment outline for the purpose of identifying patient strengths, or it can serve as the basis for self-reported or observer-rated ego strength assessment scales to measure more concretely a patient’s emerging ego strength. Table 4-3 provides an example of an observer-rated ego strength assessment scale constructed in everyday language. The assessment items in Table 4-3 suggest specific questions the therapist may ask to elicit information about the ego functions outlined in Table 4-2 and Box 4-10.

Table 4-2 Ego Functions for Assessment

| Reality Testing | Differentiating Inner From Outer Stimuli |

|---|---|

| Judgment | Aware of appropriateness and likely consequences of intended behavior |

| Sense of reality of the world and of the self | Experiences external events as real; differentiates self from others |

| Affect and impulse control | Maintains self-control; can tolerate intense affect and delay of gratification |

| Interpersonal functioning | Sustains relationships over time despite separations or hostility |

| Thought processes | Attention, concentration, memory, language, and other cognitive processes are intact. Thinking is realistic and logical. |

| Adaptive regression in the service of the ego | Relaxation of ego controls, allowing creative perceptual or conceptual integrations to increase adaptive potential |

| Defensive functioning | Defenses satisfactorily prevent anxiety, depression, and other unpleasant affects. |

| Stimulus barrier | Aware of sensory stimuli without stimulus overload |

| Autonomous functioning | Cognitive and motor functions (i.e., primary autonomy) and routine behavior (i.e., secondary autonomy) are free from disturbance. |

| Synthetic-integrative functioning | Integrates contradictory attitudes, values, affects, behavior, and self-representations |

| Mastery-competence | Performance consistent with existing capacity |

| Object constancy | Ability to provide for oneself caretaking and soothing in the absence of the caretaker. |

Adapted from Bellak, L. (1989). The broad role of ego function assessment. In S. Wetzler & M. Katz (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to psychological assessment (pp. 270–295). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree