Chapter 2. Working with children and families

Anna L. Hemphill and Annette K. Dearmun

ABSTRACT

The primary aim of this chapter and its companion PowerPoint presentation is to introduce ways of assessing the psychosocial needs of children and families and provide some tools that the health professional can draw on when working collaboratively with families. The assessment strategy is underpinned by a family systems approach and by Erikson’s (1963) developmental model.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

• Recognise the value of working with the family as a system.

• Appreciate the theoretical concepts underpinning this approach.

• Develop the knowledge base underpinning a psychosocial assessment of the child and family.

Introduction

Since the 1980s there has been a sea change in the nature of children’s nursing, from a focus on giving direct, ‘hands on’ care to working in a partnership with the family, providing support in the family’s management of the care of the child and the impact that this has on their lives. There is a growing awareness that this facilitation can be more effective if the needs and resources of the family as a whole are understood (Whyte 1992).

Consideration of the family as the unit of care has been demonstrated for over a decade, in the work of American and Canadian writers (Friedemann, 1989, Friedman, 1998 and Wright and Leahey, 1994). More recently, this concept of family nursing entered the British literature through the work of Whyte, 1992, Whyte, 1996 and Whyte, 1997. Although a family-centred approach to the care of the sick child is not new to children’s nursing, the family was traditionally seen in relation to its ability to care for the child. In other words, the family was viewed as the context of the child. A family systems approach is a new orientation in that the focus of care is on the needs of the whole family. This demands an understanding of family dynamics in relation to a given situation, and the whole family becomes ‘the client’ (Friedemann 1989). Consider the needs of the family in the scenario below.

Scenario

Scenario

Scenario

ScenarioRichard, aged 18 months, sustained a head injury in a road traffic accident at the age of 1 year and has been in hospital and ventilated since then. He is to be discharged home. He has two siblings, a newborn baby brother and a 4-year-old sister who is just about to start school. Richard’s father has recently started up his own furniture business and his grandmother, who lives locally, has just had a hip replacement.

• What are the stresses on this family?

• What are the strengths and resources?

• What would a health professional need to understand in order to devise a realistic, workable plan of care?

To work with this family in an effective, supportive and empowering way it would be necessary to understand how the family functions on both a practical and an emotional level. This understanding might be gained by spending time with the family and getting to know the individual family members. However, without a clear psychosocial assessment strategy, the family’s needs might not be fully explored and important factors that could influence the family’s coping might be missed.

Throughout this chapter, a systematic approach to the psychosocial assessment of child and family is advocated. This approach can be used in any setting and is valid for all children and families, including those requiring relatively short-term acute care, for example a child hospitalised for a tonsillectomy, and those requiring longer-term support, for example a child with cystic fibrosis.

The first part of this chapter explores the principles and beliefs underpinning the family systems approach. This is followed by a discussion of the value of psychosocial assessment. Finally, the elements of assessment are discussed, including relevant theory and practical application.

What is a family?

Activity

Activity• Think about the different types of family.

• Now do the activity on the Evolve website.

It is generally accepted that the family is the basic unit of society. However, many assumptions are made about what constitutes a family. At face value ‘the family’ might seem to be a very straightforward concept, readily understood but rarely contemplated. However, although families have internalised values and traditions, they do not exist in isolation but are influenced and determined by society and cultural norms. It is important to remember that, as such, they take many diverse forms and are open to many interpretations. In essence, the family is who it identifies itself to be, and therefore a family assessment should start by asking the family ‘who is in this family?’.

Understanding the family as a system

Thinking about the family as a system is a helpful way of understanding how families function. Family systems theory underpins the approach to psychosocial assessment taken in this chapter. First postulated by Von Bertalanffy (1968), it provides the theoretical underpinning to family therapy and this in turn has formed the fundamental basis for understanding the family within family nursing (Wright & Leahey 1994). The family is seen as a system of humans in interaction with one another (Jones 1993). It is open, in that interaction occurs with the environment outside it and influences both the family system and the environment. Change in one part of the system, for example a child becoming ill, will influence interactions throughout the system.

Wright & Leahey (1994) have identified five concepts that provide a theoretical foundation for understanding the family as a system. The following explanation draws heavily on their work. Overall, it can be seen that communication and feedback mechanisms are important in the functioning of the family (Whyte 1997):

Scenario

Scenario

• Concept 1: A family system is part of a larger supra-system and is also composed of many subsystems. The family is part of larger supra-systems, for example its local community. Within the family there will be important subsystems, for example, the parental subsystem and the sibling subsystem. Family systems have emotional boundaries that help to establish what is inside the system and what is outside it.

• Concept 2: The family as a whole is greater than a sum of its parts. The family’s wholeness is more than just the addition of another member. You can understand an individual better by understanding the way his or her family works.

• Concept 3: A change in one family member affects all family members. For example, the illness of a child impacts on all roles and relationships within the family: the mother’s role, the father’s role, their relationship, the sibling’s roles and their relationship to their parents and to the sick sibling.

• Concept 4: A family is able to create a balance between change and stability. There is always change within families as individual members develop and change. Families adjust continually to incorporate these changes and maintain some stability. At times, family life can be dominated by change, for example when a family moves to a different country or when a family member dies. At other times stability seems to dominate.

• Concept 5: Family members’ behaviour is best understood from a view of circular rather than linear causality. This is illustrated in the following scenario.

Scenario

ScenarioMary is a 3-year-old girl who has begun to wet the bed again after the birth of her sibling. When she wets the bed her mother gets angry and slaps her.

From the perspective of linear causality, the child wetting the bed causes the mother to slap her: event A causes event B.

However, from the perspective of circular causality, the mother’s anger and slap in turn affects the child’s bedwetting – the child becomes more anxious and therefore more likely to wet the bed again. Thus the cycle continues: event A affects event B, which in turn affects event A and so on.

From the perspective of circular causality, each person mutually contributes to interactions. This is an empowering rather than blaming perspective in that no one individual is viewed as causing negative situations/problems.

These concepts are further illustrated on the Evolve website, where the family system is influenced by the introduction of an additional family member.

In summary there are there are three important concepts (Whyte 1997):

• change/stability

• circularity

• boundaries.

Undertaking a psychosocial assessment of the family

Assessment is not just about gathering information it is also about establishing a relationship with a family and conveying concern about them as individuals and as a unit. The two core beliefs underpinning the family nursing approach are that:

• the central nursing function is to empower the family

• the family is capable of identifying its own needs and devising ways of meeting them.

The assessment can be a process of discovery for the family as well as for the practitioner. It prompts the family to think and talk about aspects of the family that they might not have discussed together before. Gaining an understanding of the family system will help the practitioner and family to identify ways of managing the family’s problems.

The form of assessment discussed here would be helpful to anyone working with children and families. Experience from teaching and practising this form of assessment as part of a multidisciplinary course suggests that it has value for a range of practitioners working in community and acute settings who aim to take a holistic view of the child and family. The approach is strongly influenced by Wright & Leahey’s (1994) work on family nursing but also draws on Erikson’s (1963) work on psychosocial development. It includes assessment of:

• family structure: using genograms and ecomaps as assessment tools (Wright & Leahey 1994)

• family development: including using an understanding of the family life cycle (Carter & McGoldrick 1989) and individual psychosocial development (Erikson 1963)

• family functioning: including problem solving, values and beliefs, communication, emotional life and alliances and boundaries (Bentovim and Bingley Miller, 2001 and Whyte, 1997).

Each of these aspects will be addressed later in the chapter. Throughout the process, the practitioner works with the family and helps it to identify its problems and mobilise its own coping resources (Whyte 1997).

Guidelines for effective practice

The practitioner shares his or her understanding that the health problem of the child is likely to have an effect on the whole family and that the practitioner is therefore interested in the health of the whole family. When undertaking an assessment it is important to transmit acceptance of the family as it is and to phrase questions in a way that is not discriminatory or value laden.

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practiceHow do you ask questions when you are undertaking assessment? Look at the following question:

• ‘What does your husband do?’ (i.e. ‘What is your husband’s occupation?’)

What expectations, judgements and assumptions are conveyed in this question? How could you rephrase the question to remove these?

This question could be conceived to be judgemental on a number of counts. It implies that matrimony and employment of the husband are the only acceptable states. It does not allow for the fact the mother might be unmarried, widowed, divorced or in a same-sex relationship. Perhaps it is important to reflect on the reason for wanting to know about ‘the husband’. If the intention is to gain knowledge about possible social support it might be more helpful to ask an open question that has the potential to elicit important information about the other significant family members. For example, ‘Does anyone else help you to look after John?’

Assessment of family structure

Genograms and ecomaps

These give information about the internal structure of the family and of its wider context. When assessing family structure the creation of a genogram (family diagram or family tree) is a valuable place to start an assessment for several reasons because it:

• summarises information about a family in a short period of time and in a simple way

• provides a vehicle for gaining insight into family development and functioning

• offers new insights to the family and can be a catalyst for change

• engages children, parents and adolescents in the assessment process.

A genogram broadly follows the conventions of a genetic chart. Usually at least three generations of a family are recorded, each generation occupying a separate horizontal level on the chart (Fig. 2.1).

Activity

Activity

Activity

ActivityCreate a genogram for your family:

• Represent males by a square and females by a circle.

• Represent marriage or common-law relationships by a horizontal line joining the partners.

• Denote children by a vertical line dropping down from this horizontal; they should be represented in birth order, eldest to the left.

• Record the name and age of the individual within his or square/circle.

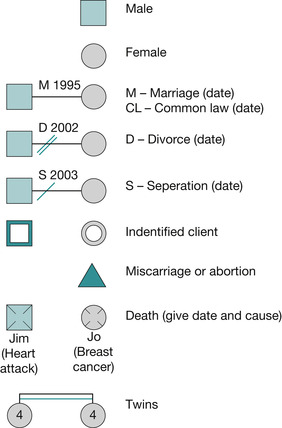

A variety of symbols are used to convey information. Those in common use are shown in Fig. 2.2.

|

| Fig. 2.2 Common symbols used in genograms. |

Tips for creating a genogram

The following helpful hints for constructing genograms have been informed by Levac & Leahey (1997):

Activity

Activity

• Define the extent and nature of the information required because this will determine the number of generations to be included in the genogram. If the concern is to identify support available within the family and/or if the child’s health problem is influenced in any way by the grandparents then a three-generational genogram will be useful. When the child/family has minor health needs then a two-generational genogram might suffice. The practitioner should be guided by the family and include those whom the family feels are significant.

• Consider ways in which the child and family can be involved in the process. To maximise the value of the genogram as a vehicle to initiate conversation and establish rapport it is important to engage the family in the exercise. This can be achieved via a number of strategies:

• begin by asking simple and concrete questions, e.g. age, occupation, hobbies, health, school, favourite games

• when the family appears comfortable, move the discussion to more complex issues, e.g. sibling relationships or parental concerns. If there is a step family it will be relevant to ask questions about custody and contact with the non-custodial parent

• if appropriate, ask family members how an absent family member might answer the questions

• overtly value each family member

• encourage the child’s active participation by taking into account his or her developmental age, asking the questions at an appropriate level and interpreting non-verbal as well as verbal responses

• evaluate the contribution of young people – their inhibitions might prevent them from participating directly and it might be necessary to ask other family members about them.

• Observe the family’s non-verbal communication throughout the process and take note of how family members express themselves as well as of the actual content (what is said).

Activity

ActivityConsider the ecomap for the Taylor family (Fig. 2.3) together with the information about the family below:

|

| Fig. 2.3 An ecomap of the Taylor family. |

Bill, Sue, Ben, Lucy and Kate are placed in the central circle. Sue gains support from her mother, from her friend and neighbour Nicola, and from her health visitor. She finds her relationship with her sister stressful and demanding. Both Sue and Bill go to church regularly and place a strong value on their life within the church. Bill has strong connections with work. He coaches a boys’ football team on Saturday morning. Ben enjoys going along with him to play. Lucy and Kate are twins. They go to nursery where Lucy has settled in well but Kate still finds it stressful and is reluctant to leave Sue.

Ecomaps

Further insight into the family support network can be gained by creating an ecomap. An ecomap depicts the family members’ interactions with the wider community. The family genogram is placed in the centre of a circle. Individuals, groups and institutions to whom the family relate are shown around the outside of the circle. Lines are drawn between family members and these outside contacts to show the nature of the relationship. Several lines represent strong connections, single lines represent weaker connections and slashed lines represent stressful relationships. Arrows can be used to illustrate the direction of flow of energy and resources. An ecomap for the Taylor family is shown in Fig. 2.3.

In summary, genograms and ecomaps enable the practitioner to gain awareness of the internal structure of the family and of its wider context. It also provides the opportunity to begin to assess demands on the family, sources of stress and support available to the family.

Assessing child and the family development

Consideration of the psychosocial development of the child and family will give insight into the stresses and challenges faced by individual family members and by the family as a whole. It is important to consider the usual developmental changes that all individuals and families experience over time because these influence and will be influenced by any health problem. In addition, the way in which a child copes with a situation will be influenced by past developmental experiences. Two theories can help with this:

•Erikson’s (1963) theory of the psychosocial development of the individual

• family life cycle theory.

Psychosocial development of the individual

Erikson’s (1963) theory is still widely accepted and used to aid understanding of children’s behaviours and emotions. He presents eight stages of psychosocial development covering the whole life cycle (Table 2.1). The individual is faced with particular developmental tasks at each age-related stage. These tasks are a response to:

• the individual’s physical and cognitive maturation

• societal demands

• cultural expectations.

| Stage | Age | Personality strength |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Trust versus mistrust | 0–1 years | Hope |

| 2. Autonomy versus shame and doubt | 1–3 years | Will |

| 3. Initiative versus guilt | 3–5: play age | Purpose |

| 4. Industry versus inferiority | 6–11: school age | Competence |

| 5. Identity versus role confusion | Adolescence | Fidelity |

| 6. Intimacy versus isolation | Young adulthood | Love |

| 7. Generativity versus stagnation | Middle adulthood | Care |

| 8. Integrity versus despair | Old age | Wisdom |

Erikson refers to the individual’s experience of working through the task as a crisis. Crisis in this context refers to normal stresses rather than extraordinary life events. The crisis requires the individual to make a fundamental shift in perspective. This experience is characterised both by the individual’s increased vulnerability and by his or her heightened potential. The tasks are expressed as a pair of alternative orientations or ‘attitudes’ towards life, the self and other people. Ideally, the individual achieves a healthy balance between these. For example, in relation to the first stage (0–1 year) – trust versus

PowerPoint

PowerPoint

mistrust – the infant would emerge with a generally optimistic view of life, trusting that his or her needs would be met. The infant would also have some awareness of danger, that some people/situations were not to be trusted.

PowerPoint

PowerPointAccess the companion PowerPoint presentation and read more about the adult stages of psychosocial development.

The ages at which individuals experience each developmental stage are likely to vary. Furthermore, the stages are not discrete – they tend to overlap. So, for example, the infant will still be developing a sense of trust at the time when he or she learns to stand up and begins to develop a sense of autonomy. It is also important to acknowledge that each stage is grounded in those that precede it and that issues from previous stages of development can be revisited at any time. The developmental stages of children are discussed in detail below. The stages relating to adulthood are described within the accompanying PowerPoint presentation.

Stages 1 to 5 of Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development

1. Trust versus mistrust: age 0–1 year

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access