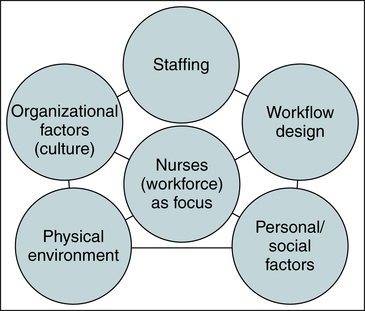

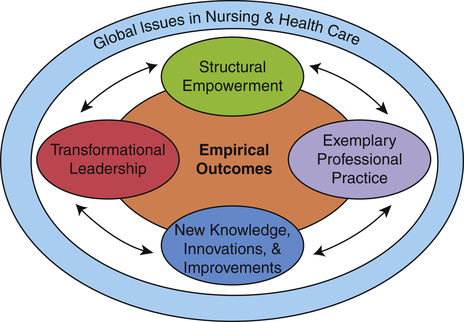

Debra D. Hatmaker, PhD, RN-BC, SANE-A After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Identify issues that affect the practice of professional nursing in the health care workplace. 2. Identify available resources to assist in improving the workplace environment. 3. Define the role of nurses in advocating for safe and effective workplace environments. 4. Describe workforce strategies that support efficient and effective quality patient care, and promote improved work environments for nurses. Additional resources are available online at: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cherry/ VIGNETTE Are any organizations within my area recognized as Magnet® hospitals? Which organizations have shared governance models? What is the content and length of orientation for new nurses? What is the organization’s philosophy regarding staff mix designations? Does the organization have a conflict resolution process? Answers to these questions can be found on health care organizations’ websites or from their nurse recruiters or nurse educators. Armed with answers to these and other questions, Elena decides to accept a position with a large tertiary care center that she believes has created an environment most supportive of ensuring the delivery of quality patient care. However, she knows that with the acceptance of this position, her role as a workforce and patient advocate has not ended; rather it has only just begun. Questions to Consider While Reading This Chapter 1. What workforce advocacy strategies can Elena use to promote quality patient care and a safe work environment? 2. What is the value of shared governance to Elena’s individual nursing practice? 4. What online resources are available to help Elena learn more about important workplace issues and workforce advocacy? 5. How can Elena gain increased marketability of her nursing expertise? In today’s modern health care system, nurses are faced with many workplace issues. These complex issues affect not only the nurse but also the patient, the organization, and the profession. This chapter attempts to identify a few select critical issues facing nurses and the nursing profession, including the nursing shortage, appropriate staffing, patient safety and advocacy, and workplace rights and safety. Workforce advocacy is defined, and its specific strategies are highlighted. To be a successful and accountable professional, nurses must recognize current issues and know where to seek support for workforce advocacy. • Prevention of premature mortality (Cho et al, 2008) • Increased hospital profitability (Unruh, 2008) • Decreased patient mortality (Aiken et al, 2009; Blegen et al, 2011; Needleman et al, 2011) As we visit Elena Gonzalez 6 months after she assumed her new position, we find that she has become involved in advocating for a safe work environment. Elena and the other nurses working on the medical unit are concerned because there is a limited amount of safe patient handling equipment available on their unit. The patients on the medical unit often have mobility issues, and the nurses are worried about suffering musculoskeletal injuries when transferring and repositioning patients. Where will they find information about ergonomic safety and other workplace safety issues? Are there regulations that require hospitals to implement safety measures to protect their staff against debilitating musculoskeletal injuries? What legal rights do nurses have to demand safe patient handling equipment? Is there an avenue to work with hospital administrators to decrease the costs associated with unsafe practices and to move toward a user-friendly work environment? All of these questions are related to workforce advocacy. Examples of workforce advocacy are included in Box 12-1. For over a century, the American Nurses Association (ANA) and its state affiliates have advocated for the professional nurse and quality patient care. Through research, continuing education, and knowledge sharing among today’s nursing community, the ANA offers powerful resources to nurses seeking to overcome workforce challenges and realize opportunities. In 2003, the ANA’s commitment to workforce advocacy was advanced with the creation of services and tools designated to help individual nurses self-advocate in their professional and personal development. This focus is on the individual nurse rather than the nurse’s workplace and addresses key elements of the nursing workforce: staffing, workflow design, personal and social factors, physical environment, and organizational factors (Box 12-2). Five opportunities and challenges for workforce advocacy programs are highlighted in Box 12-3. Other examples of workforce advocacy and specific workplace issues are discussed in the following sections. The nursing profession has a long history of cyclic shortages, which have been documented since World War II (Minnick, 2000). The shortage affecting the nation during the late 1990s and the early 2000s was a direct result of the struggle to implement managed care as a means of controlling the escalating cost of health care. What now appears to be a chronic nursing shortage has attracted significant attention from key groups including state and federal policymakers and leaders in education, health care, and manufacturing. Interventions by these groups have positively affected the shortage, resulting in growth in RN employment and nursing school enrollment. The downturn in the U.S. economy in 2009 led to an easing of the nursing shortage in some parts of the country (Thrall, 2009). This was largely due to many retired nurses re-entering the workforce due to economic pressures, nurses who had planned to retire who are holding on to their positions, some nurses working part-time who have taken full-time positions, and hospitals treating fewer patients because many people are delaying procedures or not seeking care due to loss of insurance (American Hospital Association, 2008; Buerhaus, 2008). There is more recent evidence that the focus on the nursing shortage is generating positive results: an unexpected number of young women entered the nursing workforce from 2002 to 2009 causing faster growth in the supply than anticipated. The number of full-time registered nurses 23 to 26 years of age increased steadily, by 62%, during that time—a rate of growth that has not been seen since the 1970s (Auerbach et al, 2011). Despite this positive sign of stabilization, workforce analysts caution nurse educators, policymakers, employers, and other stakeholders that considerably more progress is needed if the country is to meet the fast-growing needs for professional nurses at a time when the population is aging, more people are living with chronic conditions, and health care reform is poised to dramatically increase the number of people accessing care. The analysts (Auerbach et al, 2011) indicate that instead of declining in absolute and per capita terms as had been previously projected, the nursing workforce is now projected to grow at nearly the same rate as the population through 2030. This good news could cause some policymakers to believe that the shortage has been solved; however, analysts predict that the replacement of the retiring “Baby Boom” nurses is not going to happen over the next few years and may not be realized until the next decade. Continuing attention to the issue is necessary in order to encourage young people to remain interested in nursing. Professional nursing is the largest U.S. health care occupation according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. Department of Labor, 2011). Employment of registered nurses is expected to grow by 22% from 2008 to 2018, much faster than the average for all occupations. Thousands of job openings will result from the following: • The need to replace experienced nurses who leave the occupation, especially with the median age of RNs at 46 years (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], 2010) • Technologic advances in patient care that result in more patients accessing the health care system and needing more specialized care • Increasing emphasis on preventive care • The rapid growth in the older population, who are much more likely than younger people to need nursing care In examining the shortage of nurses, it is important to consider the nurses work environment as a contributing factor. In a comparison of three national random sample surveys of RNs, areas identified as negatively affecting nursing satisfaction were: 1) opportunities to influence decisions about workplace organization; 2) recognition of accomplishments and work well done; 3) opportunities for professional development and advancement; and 4) opportunities to influence decisions about patient care (Buerhaus et al, 2009). In a 2011 job satisfaction and career plans survey of RNs, results showed that job satisfaction is declining with 24% surveyed indicating that they will seek a new place of employment as the economy improves (AMN Healthcare, 2011). Close to half said that in the next 1 to 3 years they would consider career changes such as switching to a less demanding nursing position, working as a travel nurse, switching to part-time, or retiring. The identification and recognition of these workplace challenges charge health care systems with the unavoidable requirement to redesign work and workplace environments so that they are able to attract, retain, and develop the best RN workforce. Numerous efforts were undertaken over the past decade to recruit more students into nursing—efforts that have been largely successful. Professional nursing associations and health care companies educated the public regarding the shortage and the benefits of a nursing career. The Johnson & Johnson Campaign for Nursing’s Future, a multiyear $30-million national initiative, was designed to enhance the image of the nursing profession, recruit new nurses and nurse faculty, and help retain nurses currently in the profession (Johnson & Johnson, 2009). Unfortunately, even when attempts to recruit more people into nursing have been successful, most schools and universities find themselves unable to expand their nursing programs to accept the qualified applicants because they are faced with a serious shortage of nursing faculty. National and statewide efforts have resulted in increases in nursing school enrollments for 11 consecutive years (2001 to 2011), yet these increases will not balance out the impending wave of RN retirements or employment changes as the economy recovers (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2011a). In October 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011) released its landmark report on “The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health” initiated by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which called for increasing the number of baccalaureate-prepared nurses in the workforce to 80% by 2020 (the 2008 HRSA Sample Survey listed 50% of the RN workforce as having a baccalaureate degree or higher). This and other evidence-based recommendations contained in the report state that to respond “to the demands of an evolving health care system and meet the changing needs of patients, nurses must achieve higher levels of education” (IOM, 2011). One of the most critical problems facing nursing and nursing workforce planning is the aging of nursing faculty (AACN, 2011b). The mean age of nursing faculty has steadily increased to 60.5, 57.1, and 51.5 years for doctoral faculty at the ranks of professor, associate professor, and assistant professor, respectively. For master’s-prepared faculty, the average ages for professors, associate professors, and assistant professors were 57.7, 56.4, and 50.9 years, respectively. Unfortunately, the shortage of faculty is contributing to the current nursing shortage by limiting the number of students admitted to nursing programs. In 2011, the AACN reported that 67,563 qualified applications to nursing baccalaureate and graduate programs were not accepted, and an insufficient number of faculty were cited by schools as a reason for not accepting all qualified baccalaureate applicants (AACN, 2011b). The National League for Nursing (NLN) reported that 99,000 qualified applicants were turned away from their member schools, which are primarily associate degree programs (NLN, 2009). Faculty salaries continue to be a major contributor to the faculty shortage. According to the AACN, academic institutions, especially those faced with budget cuts, generally cannot compete with nonacademic employers when it comes to salary benefits. Past nursing shortages have proven that the retention of professional nurses is a key to any organization’s success. The ability of an organization to retain nurses primarily depends on the creation of an environment conducive to professional autonomy. Nurses want to work in an environment that supports decision making and effective nurse-physician relationships, which are critically important to patient safety. Although some progress has been achieved, RNs’ perceptions of the hospital workplace environment, as measured across three national surveys, demonstrate much need for improvement (Buerhaus et al, 2009). In the national surveys, many areas of work-related quality of life were rated poorly by RNs employed in hospitals, with fewer than one in four RNs rating them “excellent” or “very good” (Buerhaus et al, 2009). When asked to rate the quality of their relationships with others in the workplace, RNs assigned their highest overall ratings to their relationships with other RNs, followed next by their relationships with physicians and nurse practitioners, and then frontline nurse managers. RNs ranked their relationships with administration and management the lowest. In contrast to these perceptions, RNs in the surveys were generally satisfied with their jobs, and satisfaction had increased over time. The increase in job satisfaction was predicted by several factors: organizations that emphasized quality of patient care, management that recognized the importance of their personal and family lives; satisfaction with salary and benefits, high job security, and positive relationships with other nurses and with management. Decreases in job satisfaction were predicted by feeling stressed to the point of burnout, feeling burdened by too many non-nursing tasks, experiencing an increase in the number of patients assigned, and having a general negative overall view of the health care system. One of the most successful nurse retention models focuses on promoting standards for professional nursing practice and recognizing quality, excellence, and service. In 1980, recognizing a critical and widespread national shortage of nurses, the American Academy of Nurses, an affiliate of the American Nurses Association (ANA), undertook a study to identify a national sample of what were referred to as “magnet hospitals” (i.e., those that attract and retain professional nurses in their employment) and to identify the factors that seem to be associated with their success in doing so (McClure et al, 1983). This landmark study, titled “Magnet Hospitals: Attraction and Retention of Professional Nurses,” identified workplace factors, such as management style, nursing autonomy, quality of leadership, organizational structure, professional practice, career development, and quality of patient care as influencing nurse job satisfaction and low turnover rates in the acute care setting. Out of 163 hospitals initially participating, only 41 were deemed Magnet hospitals for their ability to support nurse autonomy and decision making in the workplace. As a result, the ANA’s credentialing arm, the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), began a program recognizing hospitals with excellent nursing recruitment and high retention rates. As the Magnet Recognition Program® evolved, it sought to combine the strengths of the original study with quality indicators identified by the ANA and the standards of nursing practice as defined in the ANA’s Scope and Standards for Nurse Administrators so that both quantitative and qualitative factors of nursing services were measured. The qualitative factors in nursing, referred to as the 14 Forces of Magnetism®, provided the conceptual framework for the appraisal process. In 2007, the ANCC commissioned a statistical analysis of Magnet appraisal team scores from evaluations conducted using the 2005 Magnet Recognition Program® Application Manual. This analysis clustered the sources of evidence into more than 30 groups, yielding an empirical model for the Magnet Recognition Program. The new, simpler model reflects a greater focus on measuring outcomes and allows for more streamlined documentation (Figure 12-1). With its link between quality patient care and nursing excellence, the Magnet Recognition Program has reached a coveted level of prestige within the nursing community and among acute care facilities. Research has consistently shown that Magnet hospital nurses have higher levels of autonomy, more control over the practice setting, and better relationships with physicians (Aiken et al, 2000; Aiken et al, 2008; Aiken et al, 2009; Armstrong et al, 2009; Wade et al, 2008). Magnet status is now seen as the single most effective mechanism for providing consumers and nurses with comparative information, the gold standard for quality nursing care. Nurses advocating for a strong workplace should advocate for their hospital to achieve Magnet status. As the nation works to increase the supply of professional nurses through education, strategies must be developed to retain the older, expert professional nurse within the nursing workforce. The following statistics detail the extent of the aging workforce issue (HRSA, 2010): • In 2008, the median age of professional nurses was 46 years. • In 2008, RNs younger than 30 years of age represented only 10.6% of the total nurse population. • Professional nurses 40 years of age or older represented 67.8% of the workforce, with 23.7% older than 54 years of age. There has been little research to test the effectiveness of recruitment and retention strategies with older nurses. In a qualitative study on influences on the older nurse to continue bedside practice, the authors found that the most pervasive and difficult experiences in the sample of older nurses involved dealing with stress, frustration, constant change, physical and mental declines, and dealing with intergenerational conflict (Spiva et al, 2011). Despite the challenges, the nurses in this study found positive aspects of and meaning in being a nurse—through the recollection of earlier and happier memories, making a connection with patients, and cherishing the preciousness of caring for patients and families. This and other studies on ways to keep older nurses practicing cite the following suggestions for employers in creating positive environments: • Work environment enhancements such as the unit’s physical layout, technology improvements and teamwork opportunities. • Staffing enhancements such as consistent patient-to-nurse ratios, having an admission and discharge nurse, and patient assignments based on acuity. • Work redesign ideas include eliminating semiprivate rooms, providing more workspace to decrease standing, locked medication drawers in patients’ rooms, storing supplies and equipment within patients’ rooms, bedside computers, user-friendly computer systems, and nursing units designed within a circle layout to reduce walking. Although many organizations have added on-site daycare and sick care for children of younger nurses, organizations may need to consider adding adult daycare to assist older nurses who are caring for aging parents. Creative staffing plans with shorter shifts and identified respite periods may help extend the work life of aging nurses. Technology has provided many workplace accessories that reduce the physical demands on nurses that can result in injury or stress, especially to aging nurses. The ANA’s Handle with Care® campaign aims to eliminate lifting in the hospital environment by using technology and assistive devices to do the heavy work (ANA, 2011a). Ergonomic issues are important for staff of any age, but additional attention is needed as the workforce ages. Organizations that strategically plan for an aging workforce will be best positioned to deliver quality health care to their customers. In addition to planning for retention of an aging workforce, health care is challenged to become the employer of choice for the younger emerging workforce. A number of studies have focused on the work and management expectations of today’s young worker who expects balance and perspective in the workplace. In a study focused on Generation Y (those born after 1980) nurses, recognition was reported as a key motivator. The younger nurses identified their needs as stability, flexible work schedules, recognition, opportunities for professional development, and adequate supervision (Lavoie-Tremblay et al, 2010). Elena, the young nurse described at the beginning of the chapter, will be searching for opportunities to gain advanced training, education, and certification as she seeks to make herself more marketable in her professional nursing role. She expects feedback on her performance to help refine her skills and build her confidence. She also expects her manager to take a personal interest in her, to know her name, and to help her build a competitive portfolio. Many managers are unaware of these expectations in emerging workforce employees and contribute to their hastened exit from the workplace by not attending to their personal and career needs. For several decades, the United States has regularly imported nurses to ease its nurse shortages. Internationally educated nurses represent a larger percentage of the U.S. nursing workforce in recent years with 5.1% of RNs licensed before 2004 and 8.1% of RNs licensed since that time. The Philippines has dominated the nurse migration pipeline to the U.S. and to other recruiting countries (HRSA, 2010). International nurses coming to work in the U.S. find supportive resources through the Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools (CGFNSs) including verification of the foreign nurse’s knowledge-based practice competency. The economic recession and visa retrogression have slowed down the entry of internationally educated nurses to about 50% of 2007 levels, although it is believed that numbers will again increase in the near future.

Workforce Advocacy and the Nursing Shortage

Chapter Overview

Promoting Workforce Advocacy and a Professional Practice Environment

The Nursing Shortage

Future RN Employment Opportunities

Health Care As a Challenging Work Environment

Nursing School Enrollments and Recruitment

Educational Preparation

Faculty Shortage

Nurse Retention

Magnet® Hospitals

Aging Workforce and Retention

Emerging Workforce Recruitment and Retention

International Nurse Recruitment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access