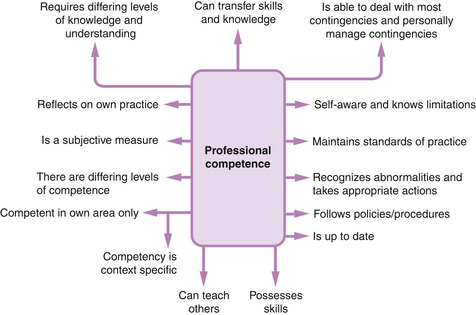

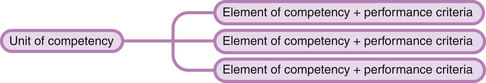

Chapter 3 Pre-registration health care education requirements in the UK The outcomes-based competency approach to professional education and assessment An outline of the background of competency-based assessment Using competency-based assessment in professional health care education Competency-based assessment for NVQs Arguments for and against the NVQ system for assessing professional practice The case for an integrated competency-based approach for assessing health care practice Using the holistic/integrated approach for competency-based assessment of clinical practice A ‘clinical skills checklist‘ for pre-registration nursing and midwifery education The health care professions have a responsibility to, and are accountable to, the public. They serve to train health care practitioners who are clinically competent and fit to practise (HCPC 2010, NMC 2001). Fraser et al (1997:51) put it very simply: However, in the nursing and midwifery professions there has been much accusation over the years that nursing and midwifery education does not produce competent nurses and midwives (Bradshaw 2000, Castledine 2000). This concern remains today (Jervis & Tilki 2011, Rutkowski 2007). It is essential that pre-registration health care students achieve the learning outcomes that will satisfy the UK Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) and the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) training requirements (HCPC 2011a, NMC 2010, 2009). It is necessary to measure and assess the standards of proficiency so that the practitioner who qualifies is clinically competent and fit to practise. The issue of being clinically competent is not just restricted to newly qualified practitioners. Nurses and midwives and registrants on the HCPC register are required to maintain their professional knowledge and competence (HCPC 2008, NMC 2008). However, the NMC (2011a) reported that approximately 37% of cases referred when the registrant’s fitness to practise is in doubt related to a lack of competence of the practitioner and not to professional misconduct. Over a decade ago, the United Kingdom Central Council (UKCC 1999) reported similar findings: there was lack of competence in a significant number of cases. In the case of registrants on the HCPC register (HCPC 2011), 19% of allegations concerned issues of lack of competence. It is therefore important to consider carefully what it means to be clinically competent. In this chapter, the use of competency statements and a competency-based model of assessment are suggested as means to be clear about what we want to assess (Hager & Gonczi 1996). The key features of the National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) system are described to illustrate how a tight structure and format for assessment can be constraining, but has the potential advantages of validity and reliability of assessment. The nature of competencies, what it means to be clinically competent and their assessment in professional practice are explored. The competency-based model of assessment is critically evaluated as an assessment tool for assessing professional practice. The nursing and midwifery professions in the UK regulated by the Nursing and Midwifery Council, and professions in the UK regulated by the Health and Care Professions Council, came into being through Acts of Parliament. The Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001 and the Health and Care Professions Order 2001 require these statutory bodies to establish standards of education and training necessary to achieve the standards of proficiency in order to be admitted to the professional registers. The standards of proficiency are set at a ‘threshold‘ level, as this is the minimum level for safe and effective practice in order to protect the public. Before a higher education institution (HEI) can provide and run a pre-registration health care course of the professions regulated by the NMC and the HCPC, the course must be validated by the relevant statutory body and the HEI. The process of conjoint validation frequently brings competing sets of demands in relation to course assessment strategies (Bedford et al 1993). The NMC and HCPC are concerned that assessment strategies are sensitive to the demands of professional practice. On the other hand, HEIs‘ concerns focus on academic credibility and the extent to which assessment strategies are sensitive to intellectual competence. In the case of nursing and midwifery, in the document Fitness for Practice, the UKCC (1999) set out a radical agenda in order to refocus nursing and midwifery education to meet the needs of the rapidly changing health service by ensuring that nurses and midwives are fit to practise. The Commission recommended that pre-registration nursing and midwifery education should utilize: This agenda is endorsed by the NMC. By refocusing pre-registration education on outcomes-based competency principles, the NMC believes that the needs of the three key stakeholders of pre-registration education – namely the NMC, the prospective employers and the HEIs – are more likely to be met. These needs underpin the NMC‘s and HCPC‘s requirements for pre-registration programmes (HCPC 2011, NMC 2010a, 2009). The needs of each of the stakeholders are set out below: • Fitness to practise. The NMC and HCPC are primarily concerned about fitness to practise – should the student be issued with a ‘licence‘ to practise? • Fitness for purpose. Prospective employers are primarily concerned about fitness for purpose – is the newly qualified practitioner able to function competently in clinical practice? • Fitness for award. Higher education institutions are primarily concerned about fitness for award – has the student attained the appropriate level, breadth and depth of learning to be awarded a diploma or degree? Gilbert Jessup, who is viewed as the most prominent English advocate of competency-based testing, argued that ‘the measure of success for any education and training system should be what people learn from it, and how effectively. Just common sense you might think…‘ (Jessup 1991:3). Jessup suggests that professional training frequently fails to make explicit statements as to what professionals should know, understand and be able to do. Practitioners need to know, with confidence, the ‘right blend of knowledge, skills and attitudes to become competent‘ (Fraser et al 1997:51) and the standard at which they are safe and effective. This knowledge will enable practice educators to conduct assessments and make assessment decisions with the assurance that students who qualify are fit for both practice and purpose. The use of an outcomes-based competency approach allows the different stakeholders to agree a set of competencies and outcomes for pre-registration programmes to cover the knowledge, understanding, skills, abilities and values expected of newly qualified practitioners (UKCC 1999). Using these competencies and outcomes, referred to as Standards by the NMC (NMC 2010a, 2009), there is a requirement for pre-registration nursing and midwifery programmes are designed to prepare the student to be a practitioner who can apply knowledge, understanding and skills to perform to the standards required in employment, and to provide care safely and competently, thereby assuming the responsibilities and accountability necessary for public protection. Jessup‘s measure of success may thus be fulfilled! Whilst the HCPC does not state explicitly that an outcomes-based competency principle is used in its pre-registration courses, like the NMC it requires Standards to be achieved in all the pre-registration courses of the professions it regulates. An examination of these standards indicates that all the elements of outcomes-based competency principles (to be discussed below) are implicit in the Standards (HCPC 2011). Two major concepts now require exploring: the nature of competence and the outcomes-based competency approach. I start this discussion by posing the question: What does it mean to be professionally competent? The NMC (2008) stipulates that competence is the individual practitioner’s responsibility. On completion of a nursing updating course in order to return to practise after a career break, Bradshaw (2000:319) came to this conclusion: What, indeed, does it take to be a professionally competent nurse or midwife, or paramedic, or occupational therapist? You may wish to discuss the questions in Activity 3.1 with your colleagues. You may have discovered that the concept of professional competence resists straightforward answers or categorization. Debates that I held with groups of nurses and midwives about the meaning of professional competence gave me much room for thought. The main aspects elicited are shown in Figure 3.1. These aspects point to the multifaceted and complex nature of competence, and what it means to be a professionally competent health care practitioner. Research in the nursing and midwifery professions by Watson et al (2002), Fraser et al (1997) and Bedford et al (1993) concluded that there is no commonly shared definition of a competent nurse or a competent midwife. Bedford et al (1993:40) think that there are: Wolf (1995), who is viewed as one expert in the field of competency-based assessment, wrote that ‘competence‘ and ‘competencies‘ are vexed terms – acres of print continue to be expended over their definitions. Rather than take the reader on a tedious trawl of these definitions, I have selected those that I see are pertinent to the discussion of competence in the health care professions. Jessup (1991:26) defines both occupational and job competence. Note that his concept of occupational competence is broader: Jessup‘s definition of competence is stated simply as ‘the ability to perform to recognized standards‘ (1991:40). He goes on to say that ‘these standards are those used to maintain or improve “quality” in the relevant occupation or profession‘. Here, Jessup reiterates the expectation of the Manpower Services Commission (1985, in Wolf 1995:31) of someone who is competent – ‘by competent we mean performing at the standards expected of an employee doing the same job‘. Eraut‘s (1998:135) definition of competence as ‘the ability to perform the tasks and roles required to the expected standard‘ reflects the definition of competence that underpins the thinking of those professions in Australia that have established competency standards. Gonczi et al‘s (1993:5) definition is as follows: The definition of competence by Gonczi et al (1993) possesses three key components: In competency-based assessments, competence is focused on performance of a role or sets of tasks (Gonczi et al 1993). Performance is directly observable, whereas competence is not: rather, it is inferred from performance, which is why competence is defined as a combination of attributes that underlie successful performance. There are numerous professional roles, such as nurses, midwives, doctors, pharmacists, physiotherapist, teachers and so on. Roles consist of a multitude of tasks, which can be further divided into sub-tasks. The approach taken by the NVQ movement in the UK focuses on the performance of discrete tasks and sub-tasks: each NVQ covers a particular area of work at a specific level of achievement (Wolf 1995). The professions in Australia have taken what Gonczi et al (1993) describe as the ‘integrated approach‘ – analysis into tasks ceases at the level of relatively complex and demanding professional activities. Competency standards consider the complex combinations of attributes that are required for effective professional activities. Gonczi et al (1993) stress that both the attributes of the practitioners and their performance of key professional tasks are essential to their definition of competence; this means that attributes of individuals do not in themselves constitute competence. Nor is competence the mere performance of a series of tasks. Rather, the notion of competence integrates attributes with performance; that is, the competent practitioner is not only able to perform, but is also capable (Worth-Butler et al 1994). Competence assessment that incorporates both performance and capability underpin the notion of ‘fitness to practise‘. The NMC (2008) and the HCPC (2008) require health care practitioners to integrate attributes with performance in their definition of ‘fitness to practise‘. Their notion of ‘fitness to practise‘ means having the skills, knowledge, good health and good character to practise safely and effectively (HCPC 2010, NMC 2010b). The NMC adds that this practice is to be without supervision. The judgement of the performance of a role and its associated tasks is either competent or incompetent – competence therefore requires that the performance be judged against pre-specified ‘standards‘. Standards specify the skills, knowledge and understanding that underpin performance in the workplace (Wolf 1995). The ‘standards‘ embody and define competence in the relevant occupational context. A ‘competency standard‘ consists of a unit of competence (representing a wide work function), which is subdivided into smaller elements of competence (tasks within the wider function) with their associated performance criteria (the standards by which the competence in the task will be judged) (Hager & Gonczi 1996). This is the framework in both England and Australia. This framework is illustrated in Figure 3.2. An example of a unit of competency and its associated elements of competency is shown in Appendix 2. An outline of the background of competency-based assessment Modern competency-based assessment (in association with competency-based education) first became important in the early 1970 s in the context of American teacher education and certification (Wolf 1995). In response to mounting public attacks on the quality of teacher education, the federal government became involved in education reform – competency-based teacher education was seen as a major panacea for the improvement of American education. In the late 1980 s in Australia, there was considerable pressure from the national government on industry and the professions to adopt a competency-based approach to education, staff development and performance appraisal (Sutton & Arbon 1994). Consequently, most of the professions have developed competency-based standards (statements) and competency-based assessment strategies (Hager & Gonczi 1996). In the UK in the 1980 s, following a Scottish lead, the government launched a huge programme of ‘standards development‘ – this produced ‘standards of competence‘ in a big range of occupational sectors, each with its associated NVQ award, or in Scotland the Scottish Vocational Qualification (SVQ). Although NVQs were approved by a national body, the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA), the actual processes of supervision and assessment were carried out by ‘awarding bodies‘ such as the City and Guilds of London Institute. The new qualifications framework for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF), has developed new qualifications to replace the Health and Health and Social Care suite of NVQs (Skills for Health 2012). Whilst the qualifications in the QCF units are competence based, QCF units differ from NVQ units in that they contain learning outcomes instead of knowledge and performance criteria statements. The reader is directed to the work of Wolf (1995), who gives a critique of competency-based assessment and the NVQ system. Competency-based assessment is a form of assessment that emphasizes the outcomes of achievement. These outcomes are specified to the point where they are clear and ‘transparent‘, so that assessors, assessees and ‘third parties‘ can all make reasonably objective judgements with respect to their achievement or non-achievement. Certification is made on the basis of demonstrated achievement of these outcomes (Wolf 1995). Can a case be made for using the competency-based approach in the health care professions? Thirty years ago, Patricia Benner (1982:303, 309) had this to say about using this approach in nursing education: Notwithstanding Benner‘s warning about competency-based education in nursing, one recommendation made in the reports Making a Difference (Department of Health 1999) and Fitness for Practice (UKCC 1999) was to refocus pre-registration nursing and midwifery education on an outcomes-based competency approach. This recommendation is endorsed by the HCPC (HCPC 2011) and the NMC (NMC 2010a, 2009). Is this recommendation justified? What are the implications of using competency-based assessment of clinical practice? An examination of two particular ways of using competency-based assessment may provide some answers: these are the NVQ system in the UK and the ‘integrated‘ approach used by the professions in Australia. The NVQ framework represents a very particular application of competency-based assessment (Wolf 1995). This section will provide an outline of the basic structure of NVQs and discuss the principles underlying competency-based assessment for NVQs. The process of assessment within the competency-based framework is discussed in Chapter 6. Inferences will then be drawn about the appropriateness of the NVQ system for the assessment of professional practice, such as in the nursing and midwifery professions. An NVQ comprises several units and their associated elements to be achieved at one of the five pre-specified levels (DfES 2005). A unit consists of a group of ‘elements of competence‘ and their associated performance criteria and knowledge specification. Each unit reflects a discrete activity or sub-area of competence – each is worthy of separate accreditation, much like an academic module in fact (NCVQ 1991). An element of competence is a description of something that a person who works in a given occupational area should be able to do; it encompasses some action, behaviour or outcome. Competency-based assessment for NVQs is made concrete through highly specified performance criteria and knowledge specification. The element of competence is assessed and validated against these performance criteria and knowledge specification. Appendix 2 provides an example of a unit, its associated elements and one element of competence with its performance criteria. Assessment requires that the individual demonstrates successfully that he/she has met every one of the performance criteria and knowledge specification, as these are the statements by which an assessor judges whether the evidence provided by the individual is sufficient to demonstrate competent performance (Wolf 1995). The NVQ approach requires assessment to be centred on whether performance meets the pre-specified standards. Performance is judged to be either competent or not yet competent only – the individual has either consistently demonstrated workplace performance that meets the specified ‘standards‘ or has not yet been able to do so. Grading is rejected – the individual either has or has not reached the required level of the NVQ. Up until 2005, each element of competence with its associated performance criteria had an associated ‘range‘. These ranges officially ‘elaborate the statement of competence by making explicit the contexts to which the element [of competence] and performance criteria apply. Also, they put limits on the specification to ensure a consistent interpretation‘ (NCVQ 1991:14). Contextualizing the performance criteria identifies the different contexts in which the individual is expected to achieve competent performance. This means that competence must also be assessed ‘across the range‘ and performance evidence is ‘normally required for every performance criteria [sic] across as much of the range as possible‘ (City and Guilds 1992). Following the review of the National Occupational Standards in Health and Social Care and the launch of the new Health and Social Care N/SVQs in February 2005 (Skills for Health 2005), the ‘range‘ has been replaced by the ‘scope‘. The statements in the scope do not appear to be as specific as the range statements. The scope is intended to give guidance on possible areas to be covered in the unit. It specifies a list of options linked with items in the performance criteria. Evidence is required for any option related to the candidate’s work area. The specification of the scope for the unit HSC35 can be found in Appendix 2. In its early years, NVQs were criticized for producing people who might be able to demonstrate performance but would have no understanding of what they were doing (Norris 1991). To fend off mounting attacks on NVQs as undemanding, and to ensure that individuals have an understanding of what they are doing (Wolf 1995), NCVQ added a separate ‘knowledge/understanding‘ list to every element of competence. Candidates are required to demonstrate that they understand all the items listed under knowledge evidence and supporting evidence. From 2005, knowledge and understanding are specified at unit level. Appendix 2 contains the ‘knowledge and understanding‘ statements required for unit HSC35. NVQs are offered at five levels to cover progression from routine and predictable work activities to the complex and unpredictable (Directgov 2012, DfES 2005). Box 3.1 details the summary of each level.

What do we assess?

Introduction

Pre-registration health care education requirements in the UK

The nature of competence

Performance

Standards

The outcomes-based competency approach to professional education and assessment

Using competency-based assessment in professional health care education

Competency-based assessment for NVQs

What do we assess?

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access