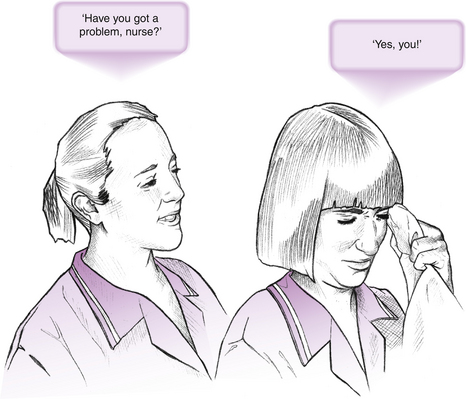

Chapter 8 Stated simplistically, the clinical environment is where patient/client care and clinical activities take place – it is where the action is. It is the real world of health care practice. A range of health professionals interact and work together to deliver care using their ‘special brand’ of professional expertise, making use of available material resources where needed. The clinical environment is unpredictable, volatile and dynamic; it is frequently noisy and teems with human interactions and activities. The clinical environment is the arena where students from the health care professions learn about care and what clinical practice is all about. The practice learning of students of health care is widely acknowledged as being one of the most important aspects of their educational preparation (English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (ENB) & Department of Health 2001). Students rate practice learning as ‘the most significant, most productive, most memorable component’ of their course (Kadushin 1992:11). It is during practice placements that students learn to care for patients and clients, colleagues and others they work and interact with. Qualified professionals further their learning and ‘hone up’ on skills and competence. The clinical environment must therefore also be an environment where learning can take place, thus becoming an educational environment. This type of setting is one that is conducive to learning and professional development. Marton et al (1984) make the important observation that learning is a function of the relationship between the learner and the environment and is never something determined by one of these elements alone. Learners do not respond merely to tasks they are assigned; rather, they adapt to and work within the environment taken as an interrelated whole. They pay close attention to the ‘hidden’ as well as the ‘visible’ curricula (Parlett & Hamilton 1977). It is the learner’s engagement with the environment that makes the particular learning experience (Boud & Walker 1990). This chapter examines the components of the clinical learning environment and those factors that contribute to a positive learning environment. Strategies for creating this type of environment are suggested. Chapter 9 examines how the learner can interact meaningfully with this environment in order to learn through clinical experiences. The learning environment of any formal educational setting is complex. It is suggested here that the clinical environment is a formal educational setting. The practice educators are the teachers and the students are required to learn. There are norms and rules of behaviours and the practice educators and students have expectations of each other and others (Boud & Walker 1990). This complexity is captured by Parlett & Hamilton (1977:14-15), who noted that a learning environment in the formal educational setting is: In the nursing literature, Dunn & Burnett (1995:1166) say that the clinical learning environment is the ‘interactive network of forces within the clinical setting that influence the students’ clinical learning outcomes’. Orton (1981) described the clinical learning environment as a group of stable characteristics unique to that setting. These characteristics will impact on and influence the behaviour of individuals within it. The clinical environment as a formal educational setting is thus much more than the physical environment where patient/client care and other clinical activities take place; it is inclusive of the material resources within it, the formal requirements, the culture, procedures, practices and standards of particular clinical areas, the expectations and interactions of all the people who are in it, as well as the personal characteristics of individuals who are part of this environment. The richness of the clinical environment provides a rich texture for learning during clinical practice. This setting provides the context and events within which the student operates and learns (Boud & Walker 1990). However, it also acts as a distraction and competes for the student’s attention. The environment for teaching and learning in the community opens another world for students. Although they do not have to work within the constraints of a hospital environment, students have to learn a different set of factors that influence practice. Professional carers are visitors in the client’s own home – caring and teaching/learning activities are carried out in the client’s domain. The client’s lifestyle, values and health priorities could challenge the student’s value systems. Students need to learn to respond sensitively in these situations as they learn about the complex forces that influence health care (White & Ewan 1991). You may wish to try Activity 8.1. 2. Learning opportunities and experiences ‘provided by’: 3. Staff commitment to teaching and learning: In nursing much of the work that explored the direct influences of the leader of the team on the learning environment was done in the 1980s in the UK. Until the mid-1980s in the UK, one of the key roles of the ward sister was to teach, supervise and assess student nurses. The ward sister was the only person who was directly responsible for student learning during clinical practice. The ward sister as the leader of the ward team was seen to be the single most important person in creating the learning climate (Jacka & Lewin 1987, Fretwell 1982, Ogier 1982, Orton 1981, Pembrey 1980). A positive learning climate is characterized by a democratic non-hierarchical structure and teamwork and good communication are displayed. The conclusion that can be drawn from the work of these researchers is that, for learning to occur, the clinical area has to be managed by a leader who is in touch with the needs and abilities of her team. The leader should also have the ability to create an atmosphere conducive to learning, a point that is developed below. Ogier (1989:37) has perhaps captured these messages in the following succinct statement: ‘facilitating learning cannot be divorced from competent management and humane leadership’. The reality today is that the team leader as ward manager has a wider diversity of roles to fulfil. This has resulted in removing the ward manager from much, if any, direct patient and student contact. Nevertheless, the importance of the ward manager’s indirect influences on the learning climate should not be underestimated. The positive attitude of the ward manager towards students has been found to be important in influencing the circumstances for a positive ward learning culture (Saarikoski & Leino-Kilpi 2002, Dunn & Hansford 1997). With the support of a ward manager who is committed to the training and development of students and staff, team members are more likely to be motivated in their role of practice educator to students, and to the development of the clinical environment into an educational environment. Each member of the team can contribute to an environment that fosters learning. The NMC (2008a) expects nurses and midwives who are practice educators to create an environment conducive to learning. Orton (1981) found that in wards that were highly rated by students there was a combination of teamwork, consultation and an awareness of the needs of others. In these wards, students’ and patients’ physical and emotional needs were amply met. A ward team that is committed not only to delivering a high standard of patient/client care but also to learning and assessing activities will contribute much to the creation of an educational climate. In a later study, Fraser (1994 in Gilmore 1999) also found that, where the ward culture was positive, there was good teamwork. Students and staff used terms such as ‘friendly’, ‘happy’, ‘involving’, ‘teaching’ and ‘explaining to students’. Such a ward culture was perceived to be as important as or more important than individual practitioners in helping students learn. Interprofessional learning and collaboration: Remember also that members of the multi-professional team make up the team even though they are not as visible as nurses and midwives in the clinical area. The multi-professional team’s philosophy of patient/client care and their attitudes towards learning and students will also greatly influence the learning environment. It is important that they contribute to the educational environment so that not only do all members of the team learn with and from each other, but also a spirit of teamwork may be created for the benefit of the patient/client. The delivery of high-quality health care requires partnership by practitioners within and between professions (Lait et al 2011), and students must ‘learn to learn and practise collaboratively and interdependently’ (Taylor 1997:5). Taylor goes on to say that ‘the complexity of a post-modern society means that problems presented to practitioners and structures to respond to them requires responses which go beyond those traditional, rigid professional boundaries’(Taylor 1997: 5). Students should therefore gain, where possible, experience as part of a multi-professional team so that they learn to function as an effective team member (Lait et al 2011, ENB & Department of Health 2001). Now you may wish to try Activity 8.2. The health care team is a complex one. Students need to learn to relate and work with the team members: this is demanding, as it is not easy for students to feel valued as good team members (Stengelhofen 1993). In particular, new students may feel anxious even with the simple act of speaking with a professional, especially when that person is viewed as a senior member of the team. Practice educators should ensure that students have opportunities to experience teamwork through observing different members of the team at work and working as a member of the team. The following ideas, based upon and extended from the work of Lait et al (2011) and Stengelhofen (1993), are offered to help students fit into the team and to learn about multi-professional team working: 1. Ensure that students have opportunities to fit into their own professional team – the ‘home team’. Initially, this can be done informally by introducing the student to these team members. Students should be invited to attend staff meetings, journal clubs, training days, seminars, social events and so on. Arrangements can also be made to enable students to observe the team members – this need not involve any teaching. In preparation for the observational activity, students should be briefed on those specific aspects of the job role that are pertinent to the student’s learning and development at the time. It is important that students demonstrate the ability to fit into the ‘home team’ before they are expected to become a member of the multi-professional team. 2. Meeting members of the multi-professional team. Introducing students to members of the multi-professional team informally – in the corridor, during coffee and meal breaks and in the staff room – can help others recognize new students. Later on, students can be gradually introduced to the work of these team members by making arrangements for students to observe them providing care for patients and being involved in situations that do not make any professional demands on the student, such as attending a team meeting and case discussion. These activities will increase the student’s understanding of the roles of the multi-professional team and also give students opportunities to interact with these professionals. 3. Meeting, working and learning with students from other professions. If your setting has students from the other professions, explore opportunities for these students to meet and perhaps work together (e.g. discussing a patient/client they have looked after). These sessions will require to be facilitated to ensure that learning is collaborative (Holland 2002). Each student will be able to contribute to the discussion of care given, viewed from the perspectives of that particular professional group. Students will also be able to learn about the roles of some of the other professionals in this way. Respect for each other’s professional roles is likely to be engendered. Students are thus engaging in interprofessional learning as they will be learning from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care (Barr et al 2005, in Lait et al 2011). This strategy sows the seed for good team working, as students who have such positive experiences of the multi-professional team are likely to carry this into their professional practice. 4. Working with members of the multi-professional team. Plan graded steps to team involvement. As students’ confidence increases they can be placed in situations where they are required to work alongside a member of the multi-professional team. In the first instance, be careful to involve the student with professionals who are patient and cooperative. The student should gradually become independent in interacting with all team members and develop the confidence to participate in care. 5. Learning actively from members of the multi-professional team. Encourage students to talk to these team members to gather information or discuss management of specific patients/clients who have required multi-professional input. The practice educator can assist the student to draw up the aims for the meeting and, subsequently, hold a debriefing session on the conduct and outcome of the meeting. Students will then be able to learn about the contribution that each professional makes to the care of that patient/client. This type of experience will make interprofessional collaborative care real for students. Lait et al (2011) cited the example of a physiotherapy student who participated in the care of a patient with traumatic brain injury. The student interacted with and interviewed the nine types of professionals involved in the care of this patient to understand their contributions. 6. Explore ways information is communicated within the multi-professional team. As well as the use of formal letters, written reports and documentation in the patient/client’s case notes, discuss other ways that communication takes place within the team, such as chats over coffee, telephone calls, during ward rounds and verbal reports. Students bring their own personalities, dispositions, hopes and aspirations, past experiences and backgrounds, and also worries and anxieties, to the clinical setting. For many beginning students, the impact of the clinical environment can be strong (Lefevre 2005, White & Ewan 1991). They have to deal with the unpleasant experiences such as sights, smells and cries of pain and difficult problems such as the abusive or disturbed patient/client. Many will not have done shift work, or been on their feet for long hours. Students who come from an affluent and comfortable home background may have to learn to cope with the realities of social and economic differences, particularly when in the community setting. Unlike permanent members of the team, students are more likely to feel like a visitor or short-stay resident (Parlett & Dearden 1977). And if they are not made to feel welcomed or, worse, if they are made to feel a burden (Phillips et al 2000), their plans, hopes and aspirations can be thwarted, and any worries and anxieties compounded by an uncongenial environment. Learning is likely to be affected negatively in this type of environment. Learning plans may be abandoned (Boud & Walker 1990). White & Ewan (1991) think that the differences between learning in the classroom and in the clinical setting are profound – in the classroom setting, students can ‘hide’ behind the mantle of the group, which shields them from the close attention of the teacher. In the clinical setting, students are visible as they work closely with their practice educators and members of the team. Patients and clients may be observing their performance. They can feel threatened and vulnerable, as their performance and behaviours are visible and open to the scrutiny of a range of people. It is important to recognize the differing needs of recent school leavers and mature students with, and without, health care experience. Learners also have different learning styles – these need to be utilized to maximize student learning (McAllister 1997). Each student forms part of the educational environment, enriching it with his/her personal contribution (Boud & Walker 1990). On entry into the environment, students create interactions that become learning experiences for themselves and others. Lincoln et al (1997) believe that students who have chosen to become health care professionals tend to be committed to the ethos of caring and curing. Clinical practice provides the opportunity for students to experience their desires to care and help and to put into practice the theory they have learned – they will be learning how to care and to develop the competencies required of a professional. Stengelhofen (1993:48) points out that it is unfortunate if a student is not seen as a student member of the department or team. They should be viewed as valuable student members of the team with specific clinical learning needs, rather than as valuable members of the team with the emphasis on ‘getting the work done’ and in providing a service contribution (Melia 1987). A clinical environment that is an educational environment will be able to support students so that they achieve their personal and professional goals in the best possible ways. This seems to be in the hands of practice educators – Eraut et al (1995) report that qualified clinical staff exercises a major influence on the quality of pre-registration programmes. Students become professionals through the process of ‘professional socialization’, which takes place predominantly in the clinical setting (McKenna et al 2010, Lincoln et al 1997, McAllister 1997, Melia 1987). They need to acquire that ‘set of values, attitudes, knowledge and skills which are displayed within the culture of a profession by practising professionals’ (Lincoln et al 1997:75). From their review of the literature on the components of professionalism, Lincoln et al identified the following four components: • professional interpersonal skills, encompassing communication skills, values and attitudes of the professional • knowledge of professional standards of conduct • ethical competence, which is essentially about moral obligation to those for whom professionals care. It is suggested here that the patient/client care practices of a clinical environment will significantly influence the professional socialization of a student. A clinical environment that is also an educational environment needs to espouse a philosophy of care, reflected in practice, which will enable students to develop into professionals who can truly meet the needs of society for care and caring. The ENB & Department of Health (2001) recommend that the philosophy of care should be in the form of a written statement. High standards of care need to be modelled. As discussed earlier, Orton (1981) found that wards that were highly rated by students amply met the physical and emotional needs of patients. There are other studies that have also found that students value high standards of care being modelled (Saarikoski & Leino-Kilpi 2002, Kotzabassaki et al 1997, White et al 1994) White & Ewan (1991) make the point that simply setting a good example for students to follow is not enough. Students must be encouraged to be active in experiencing, discussing and evaluating professional behaviours and care in order to extract personal meaning. It has long been accepted that using the ‘apprenticeship’ system in nursing and midwifery training is educationally unsound (Fretwell 1982, Ogier 1982, Pembrey 1980). What is known about learning in the workplace tells us that learning is ineffective if students are placed in practice environments as part of the workforce where supervision is inadequate and active facilitation of learning does not take place (Spouse 2003, 1998, Jacka & Lewin 1987, Melia 1987). Within the apprenticeship system, the clinical environment for students was in effect a working environment and not an educational environment. Project 2000 (UKCC 1986) challenged the ways that students were expected to learn during clinical practice. As a consequence, students currently undertaking pre-registration nursing and midwifery programmes enjoy supernumerary status. The NMC (2008) makes it a mandatory requirement for all students on approved educational programmes to be supervised by a practitioner who is capable of supporting learning and assessment in practice, making judgements on fitness for practice to enter the register or to record a specialist practice qualification. These practitioners are accountable to the NMC for such judgements. The fulfilment of these responsibilities is not so easy and straightforward and frequently causes dilemmas for the practitioner who is both mentor and assessor to the student (Bray & Nettleton 2007, Neary 1997b, Holloway 1985). However, the ethical and legal implications of mentoring, supervising and assessing students have to be considered: these are discussed in Chapter 2. Mentoring: In Greek mythology, Mentor was the wise and faithful advisor to Odysseus. Today, the mentor is a friend, role model, an able advisor and the person who supports in many different ways. Within these functions, the mentor generally takes on the roles as carried out by the assessor, participating actively in formative assessments, but does not conduct summative assessments. Much has been written about mentors and mentorship in the nursing literature (Jokelainen et al 2011, Spouse 2003, 1996, Gray & Smith 2000, Andrews & Wallis 1999). It is well documented that effective supervision, support and facilitation of learning require the mentor to possess certain qualities and skills. Andrews & Wallis (1999:204) report that the literature contains a ‘comprehensive catalogue of personal attributes and skills required for effective mentoring’. Students have certain expectations of their mentors and find certain characteristics and behaviours in mentors helpful (Lefevre 2005, Papp et al 2003, Jackson & Mannix 2001, Neary 1997a,b, Spouse 1996, Darling 1984). A common theme is the significance of the personal and professional attributes of the mentor such as approachability, good interpersonal skills, self-confidence, someone who respects and shows interest in students and a competent and enthusiastic practitioner. According to Neary (2000:21), the mentor who can contribute to the clinical environment so that it is an educational environment is the person who is: • prepared to allocate both time and energy to the role • up to date with professional practice and is innovative • competent in the core skills of coaching, counselling, facilitating, giving feedback and networking • interested and willing to help others • able to demonstrate the many characteristics advocated by Darling (1984). These characteristics are described in full below to enable you to assess yourself. Characteristics of a mentor: In her research into the characteristics that students perceive as valuable and helpful in a mentor, Darling (1984) has identified the following: • a model the student can look up to, respect and admire • an envisioner who gives a picture of what could be done, is enthusiastic about opportunities and possibilities and interest is sparked • an energizer who is enthusiastic and dynamic and kindles the student’s interest • an investor who makes time for the student; spots potential and capabilities; trusts, ‘lets go’ and delegates responsibility • a supporter who listens, is warm, caring and encouraging and is available in times of need • a standard-prodder who is very clear about what level of achievement is required and pushes and prods the student to achieve higher standards • a teacher-coach who guides on problem solving and setting priorities, helps in the development of new skills and inspires personal and professional development • a feedback giver who can offer both positive and constructive feedback and help the student explore things that go wrong • an eye opener who motivates interest in new developments and research, facilitates reasoning and understanding and directs the student into seeing the bigger picture • a door opener who provides opportunities for trying out new ideas and suggests and identifies resources for learning • an idea bouncer who not only discusses and debates issues and ideas, but also clarifies and stimulates new thoughts • a problem solver who is tolerant of shortcomings and skilfully uses both the strengths and weaknesses of the student to enable further development to take place • an educational counsellor who is trusted, understands the student’s needs to achieve, and supports and guides towards success • a challenger who questions opinions and beliefs, forces the student to examine choices critically while empowering the student towards fulfilment of her/his potential. Morton-Cooper & Palmer (2000) pointed out that mentors do not have the magic abilities or power to fashion great individuals. They do, though, enable individuals to discover and use their own talents, encouraging and nurturing their unique contributions and to assist them in becoming successful in their own right. Mentors have their own educational experiences, knowledge base, level of competence and history of experiences of caring and practice. These variations will influence the ways individuals practise their roles and how they view the work environment. Phillips et al (2000) found that many practitioners were enthusiastic about having students in the clinical areas and looked forward to sharing knowledge and experiences. Such attitudes will clearly influence the learning climate of the area positively. Conversely, there were practitioners who were so caught up with the ‘busyness’ of the workplace that students were viewed as an additional burden. The reality about clinical areas is that pressures, busyness and workloads are continually increasing; there is simply no time to ‘teach’. This is where the individual’s beliefs about how learning takes place can influence the learning climate. Jarvis (1983) and Rogers (1983) believe that teaching is not essential to learning. Many learners acquire knowledge, skills and attitudes independent of any formal teaching. This is not to say that teaching is unimportant but, given certain conditions, most adults engage in much more learning than is often realized and acknowledged. One way that students learn in the clinical setting is by observing their mentors as they work alongside each other. No formal teaching is done here. McLeod et al (1997:54) state that ‘students learn most from observing the actions and understanding the reasoning processes of their role models’. The adage ‘actions speak louder than words’ aptly describes the power of role modelling, as the actions of the practitioner are probably more powerful in influencing the student than what is said, and what is said by the practice educator is probably more powerful than what is said by the teacher in the classroom (Stengelhofen 1993). Charters (2000) thinks that this form of facilitating learning has been overlooked or devalued by the very practitioners who employ it. Being a role model is widely recognized as critical in teaching, coaching and shaping as it is the most powerful teaching strategy available to practice educators (McLeod et al 1997). ‘Attitudes take time to describe or explain, but are quickly demonstrated by every action and word’ (Ogier 1989:36) – attitudes are modelled and learnt by the way the patient/client is spoken to; skills and techniques are demonstrated when care is carried out – all are ways of working and learning at the same time. By working and talking with the student, the practitioner is teaching as well as getting the work done. Read the following modified extract (Examples 1 and 2) from Ogier (1989:25-26) and then tackle Activity 8.3. The scenarios took place on a busy general surgical ward. Mary is a second year student nurse. Postoperative analgesia was being prepared. Preparing and giving the drug took the same length of time in each example, but in Example 2 the practice educator was sharing her decision-making process – why the pethidine was being given. Mary also gained an insight into the planning of more effective pain relief. She has learnt through experience, which was triggered by the practice educator’s explanation while they worked together. The practice educator also showed interest in how Mary was progressing. Ask yourself the following questions: Patients and clients and opportunistic teaching and learning In practice-based health care professions, the best place for learning about care delivery is in the direct context of patient/client care. Burnard & Chapman (1990:48) made this important statement: These learning opportunities are difficult to control as the presence of which patients or clients in the clinical area cannot be prescribed. However, the nature of the conditions, illnesses or problems of patients and clients who require care in any given clinical setting are known. On this basis, the learning opportunities and clinical experiences that can be provided for students in each setting can be determined. Using these learning opportunities, learning contracts and assessment plans (see Ch. 6) can be developed to meet the needs of the student. Although these plans provide the structure to assist the student achieve learning outcomes, the control and predictability of experiences are unlikely to be possible. Each patient or client is different and each has varied needs that require different care and management. The condition of the patient/client could alter, sometimes dramatically. These differences and the unplanned and unpredictable events are learning opportunities that can be capitalized upon. The way that an unprecedented clinical event is responded to is a learning opportunity in itself. White & Ewan (1991:138) remind us that ‘opportunistic teaching is not dependent on the ease of availability of interesting or unusual events but on making opportunities for students to learn’. Opportunistic experiences emerge as the realities of clinical practice unfold. These authors go on to say that the ‘ability to see opportunities and use them distinguishes [practice educators] as persons with ingenuity and flair’ (White & Ewan 1991:138). For example, during the course of performing ‘routine’ pressure area care with the student, there are opportunities for involving the student actively in the care of the patient/client by, for example, inviting the student’s opinions on the condition of the skin and how the student would manage the situation, pointing out the warning signs of impending pressure sore development, which the student may not have seen, or discussing evidence-based management of pressure areas to prevent pressure sores, the policy of the clinical setting or hospital for the management of patients/clients at risk of developing pressure sores, and so on. If a relative is present who wishes to be involved in the care of the patient/client, involving the relative with care giving will show the student how this is done and the role of family members when a relative requires care. Subsequently, discussions with the student on this aspect of care will reinforce learning. You may wish to try Activity 8.4 to help you consider the vast range of activities related to direct patient/client care, which are some of the learning opportunities present in your clinical setting.

The clinical environment as a setting for learning and professional development

Introduction

The clinical learning environment

The people

The members of the team

The students

The practice educators

Learning opportunities and experiences

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The clinical environment as a setting for learning and professional development

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access