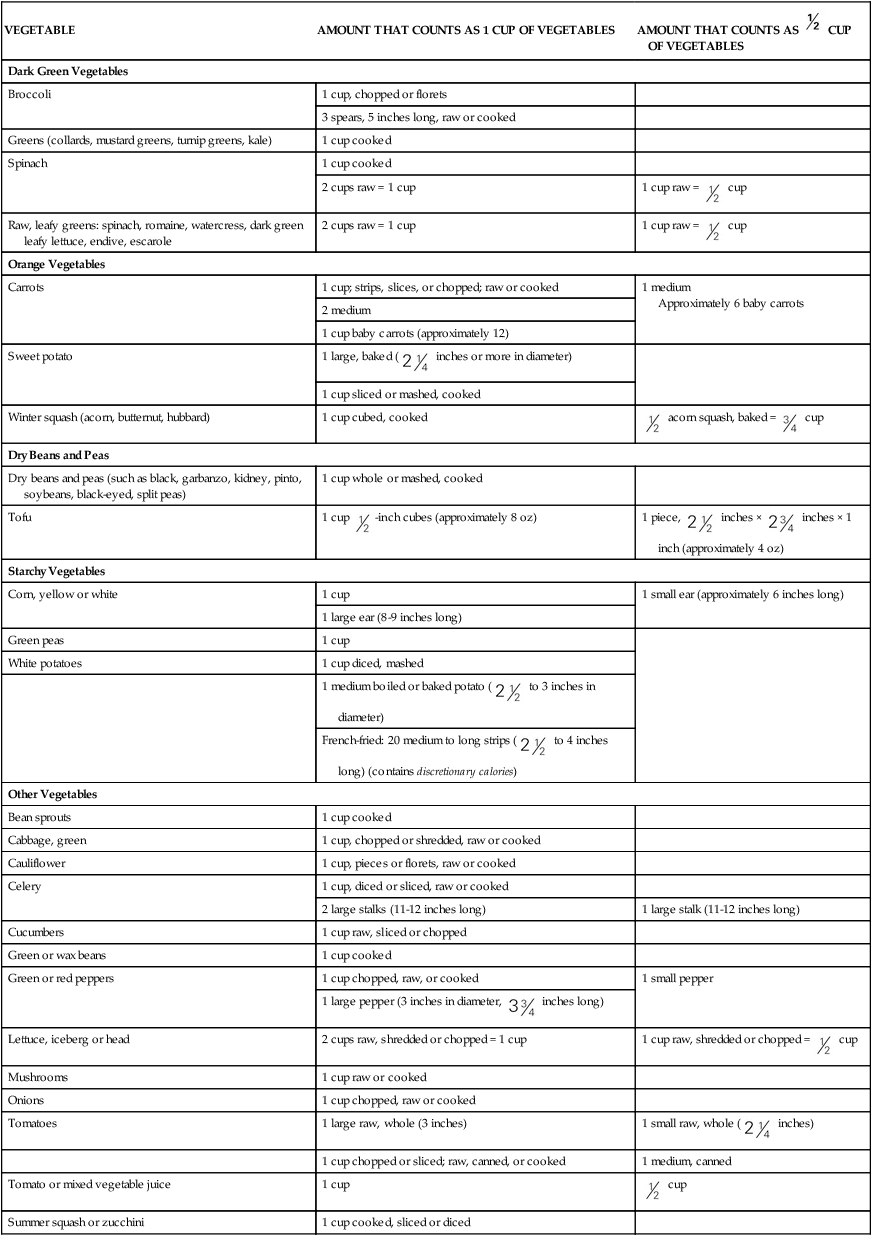

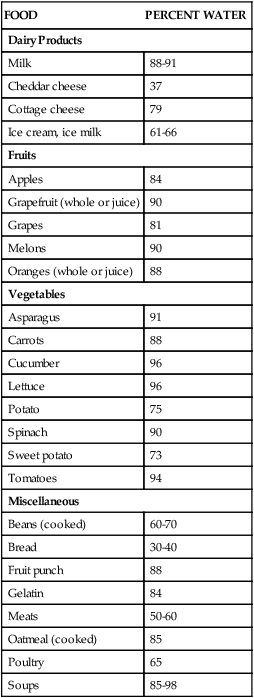

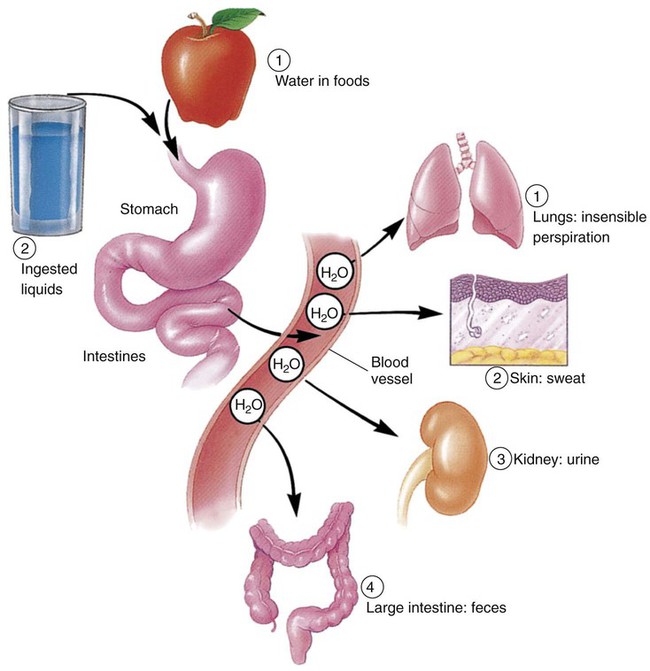

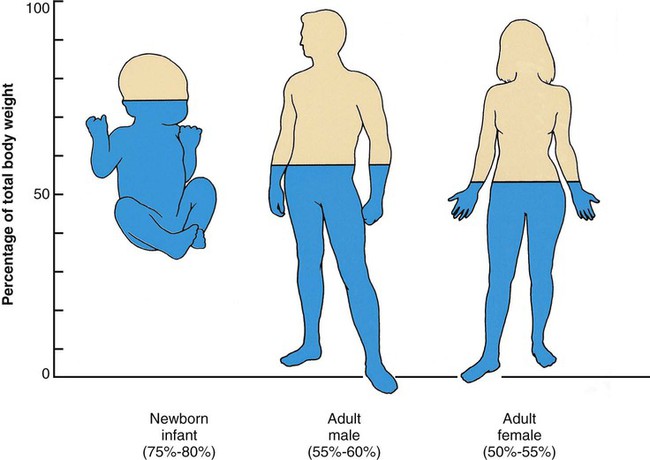

The Adequate Intake (AI) recommendations for water are about 13 cups a day for men and 9 cups a day for women. This amount is in addition to fluids from foods consumed throughout the day, such as fruits and vegetables.1 Although the minimum amount needed by healthy adults may be about 4 cups, higher amounts are optimum considering an individual’s physiologic status and energy output. Our primary source of water should be the liquids we drink (Table 8-1). Notice that coffee, tea, alcohol, and soft drinks are not listed as primary sources. Although they do contain water, coffee, tea, and alcohol act as diuretics, which cause an increase in water loss via the kidneys as urine. Soft drinks add fluid to the body, but they contain solutes (sugar, salt, various chemicals) that must be diluted as they enter the bloodstream. Drinking a soda increases the concentration of these solutes in the blood. The body responds by pulling fluid from the cells into the bloodstream to dilute the sugar and salt. The body loses the increased fluid in the bloodstream when it is excreted as urine. In addition, the body responds to the increased solutes and decreased fluid content by once again triggering the thirst mechanism. TABLE 8-1 FOODS AS SOURCES OF WATER (BY PERCENTAGE) Data from U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Nutrient data laboratory, Washington, DC, Authors. Accessed February 12, 2010, from www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl. Bottled water has become a mainstay in U.S. beverage selections and an economic force. Sales of bottled water have reached to more than $11 billion.2 Products range from imported sparkling mineral waters to spring waters to waters treated from nearby reservoirs. Although the price range is equally broad, the common denominator is that Americans enjoy the convenience of water as a beverage when available in portable containers and single portions. To reduce the chance of lead leaking into drinking and cooking water, do the following: • Run the water for 2 minutes after it has been standing in the pipes. • Use only cold water for drinking, cooking, and preparing baby formula (cold water absorbs less lead than hot). Poorer countries throughout the world continue to struggle with unsafe water supplies (see the Cultural Considerations box, Who Will Bring Water to the Bolivian Poor?). Without the financial and technologic knowledge and resources, many people become ill by consuming bacteria-contaminated water. Increased incidence of stomach cancer is associated with exposure to Helicobacter pylori, which is sometimes found in contaminated waters. The structure of water—two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom—allows it to provide a base for biochemical reactions in the body and to easily move through the various compartments of cells and body systems. As the basis of body fluids, water can host other substances of different electrical charges and characteristics. Intracellular fluids (within the cell) are composed of water plus concentrations of potassium and phosphates. Interstitial fluids (between the cells) contain concentrations of sodium and chloride. Extracellular fluids include interstitial fluid and encompass all fluids outside cells, including plasma and the watery components of body organs and substances (Box 8-1). Although not metabolized or broken down by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract processes, water is an integral component of metabolic processes. In some reactions, the water of metabolism is water released as a byproduct of oxidative reactions; in others, water may be a part of the process to release energy from adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 9. The released water may be excreted as waste or used elsewhere in the body. Glycogen in muscle and the liver contains water in the structure of glycogen molecules. When glycogen is used for energy, the water becomes available for body functions. Water performs a variety of vital functions in the body (Box 8-2). It is an important structural component of the body, giving shape and rigidity to cells. It assists in regulating body temperature. Water conducts heat, absorbing and distributing it throughout the body, keeping body temperature stable from day to day. Water also helps cool the body by evaporating invisibly from the lungs and the surface of the skin, carrying off excess heat. This type of water loss is called insensible perspiration. Our bodies have delicate but efficient mechanisms for maintaining appropriate fluid levels. The intake of fluids is balanced with the output through urine, sweat, feces, and insensible perspiration (Figure 8-1). Regulation of fluid in the body is of physiologic importance because water makes up 50% to 60% of the weight of an average adult; the percentages are even higher for infants, whose body weight is 75% to 80% water (Figure 8-2). Fortunately, all we need to do is take in enough fluids and our bodies’ natural systems take care of the rest. Water intoxication refers to the consumption of large volumes of water within a short time, which results in a dilution of electrolytes in body fluids. It causes muscle cramps, decreased blood pressure, and weakness. Water intoxication is also possible if there is extensive loss of electrolytes because of dehydration, and rehydration is accomplished using only water, without the addition of replacement electrolytes. This condition is relatively rare but tends to occur when athletes continually hydrate without equivalent loss of fluid while participating in slower-paced events such as runs lasting longer than 4 hours or extend triathlons or rehydrate after a strenuous event with excessive amounts of water. Nonetheless, fluid volume deficit, dehydration, is much more common and more dangerous for athletes.4 Minerals serve a variety of functions in our bodies (Box 8-3). Structurally, minerals provide rigidity and strength to the teeth and skeleton; the skeletal mineral components also serve as a storage depot for other needs of the body. Minerals, allowing for proper muscle contraction and release, influence nerve and muscle functions. Other functions of minerals include acting as cofactors for enzymes and maintaining proper acid-base balance of body fluids. Minerals are also required for blood clotting and for tissue repair and growth. Based on the amount of each mineral in the composition of our bodies, the 16 essential minerals are divided into two categories: major and trace minerals. To maintain body levels of major minerals, these minerals are needed daily from dietary sources in amounts of 100 mg or higher. In contrast, trace minerals are required daily in amounts less than or equal to 20 mg (Box 8-4). Although the required amounts differ greatly between the major and trace minerals, each is absolutely necessary for good health. The Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) listed in this chapter for minerals are those for young adults ages 19 to 24.1 Levels for other groups are noted when special mention is needed. Keep in mind that because nutrition is a relatively young science, new functions of minerals as nutrients in the human body are still being discovered. The prime sources of minerals include both plant and animal foods. Valuable sources of plant foods include most fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains. Animal sources consist of beef, chicken, eggs, fish, and milk products. The discussions of individual minerals highlight the best food choices (Box 8-5). Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the body. Almost all of the calcium in the body, about 99%, is found in our bones, serving structural and storage functions. The other 1% of body calcium is released into body fluids when blood passes through bones; this constant interaction of blood with bone allows calcium to be distributed throughout the body. Other functions that depend on calcium include (1) the central nervous system, particularly nerve impulses; (2) muscle contraction and relaxation, when needed; (3) formation of blood clots; and (4) blood pressure regulation. Continuing research supports that increased levels of calcium (and vitamin D) intakes may be protective for colorectal cancer.5

Water and Minerals

Water

Food Sources

FOOD

PERCENT WATER

Dairy Products

Milk

88-91

Cheddar cheese

37

Cottage cheese

79

Ice cream, ice milk

61-66

Fruits

Apples

84

Grapefruit (whole or juice)

90

Grapes

81

Melons

90

Oranges (whole or juice)

88

Vegetables

Asparagus

91

Carrots

88

Cucumber

96

Lettuce

96

Potato

75

Spinach

90

Sweet potato

73

Tomatoes

94

Miscellaneous

Beans (cooked)

60-70

Bread

30-40

Fruit punch

88

Gelatin

84

Meats

50-60

Oatmeal (cooked)

85

Poultry

65

Soups

85-98

Water Quality

Water as a Nutrient in the Body

Structure

Metabolism

Functions

Regulation of Fluid and Water in the Body

Fluid and Electrolytes

Imbalances

Fluid volume excess

Minerals

Mineral Categories

Food Sources

Major Minerals

Calcium

Function

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

cups of vegetables every day.

cups of vegetables every day. cup are also shown) toward your recommended intake.

cup are also shown) toward your recommended intake. CUP OF VEGETABLES

CUP OF VEGETABLES cup

cup cup

cup inches or more in diameter)

inches or more in diameter) acorn squash, baked =

acorn squash, baked =  cup

cup -inch cubes (approximately 8 oz)

-inch cubes (approximately 8 oz) inches ×

inches ×  inches × 1 inch (approximately 4 oz)

inches × 1 inch (approximately 4 oz) to 3 inches in diameter)

to 3 inches in diameter) to 4 inches long) (contains discretionary calories)

to 4 inches long) (contains discretionary calories) inches long)

inches long) cup

cup inches)

inches) cup

cup