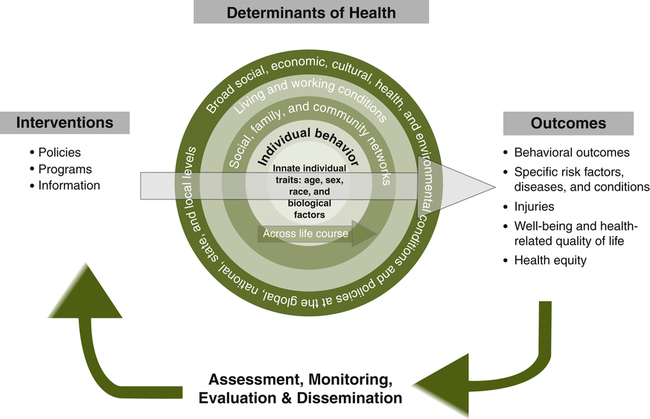

Marilyn Grace O’rourke, DNP, APHN-BC At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Define the concepts of vulnerability, risk, cumulative risk, relative risk, social determinants of health, social equity, and health disparities. • Discuss individual and societal factors that contribute to vulnerability. • Discuss the roles of Healthy People 2010 and Healthy People 2020 in reducing health disparities. • Recognize current critical issues contributing to vulnerability. • Describe nursing strategies at the individual, family, group, and societal levels to reduce health disparities in vulnerable populations. Why should nurses study the concept of vulnerability and the needs of vulnerable populations? Shi and Stevens (2005) give the following five reasons: 1. Vulnerable populations have greater health needs than the general public. 2. The prevalence of vulnerability is increasing in the United States. 3. Vulnerability is influenced by social forces, so societal forces rather than individual effort are required to remedy it. 4. Vulnerability is fundamentally linked to the overall health and resources of the United States. 5. Interest in ensuring that health care is delivered in a fair and equitable manner is increasing. What is meant by vulnerability, and what are vulnerable populations? To be vulnerable means to be susceptible to wounding or injury. Certainly, the infant and elderly woman in the waiting room fit this definition by virtue of their ages. But what about the others? What makes them vulnerable? Flaskerud and Winslow (1998) say that vulnerable populations are groups of people who have limited resources and are at increased risk for developing poor health. They list the poor, persons subject to discrimination or intolerance, those who are politically marginalized, women and children, ethnic people of color, immigrants, gays and lesbians, the homeless, and the elderly as vulnerable groups. Aday (2001) indicates that high-risk mothers and infants, the chronically ill and disabled, persons living with HIV/AIDS, the mentally ill and disabled, alcohol and substance abusers, the suicide and homicide prone, abusing families, homeless persons, racial and ethnic minorities, and immigrants and refugees fit into such groups. She divides these groups into three categories on the basis of where their principal needs lie: physical needs, psychological needs, or social needs. For example, Aday places homeless persons in the category of primarily having social needs, such as housing and employment. Depending on the circumstances involved, an individual could fit into multiple categories. For example, consider a person with a chronic illness who loses his employment because of absenteeism, begins drinking excessively, and becomes abusive toward his spouse; this person would fit into all three categories. Most literature says that anyone who is of low socioeconomic status (SES) as measured by education, occupation, and income is vulnerable to poorer health. • Their needs are serious or even debilitating and life-threatening. • They require significant medical and nonmedical services. • Their needs place increasing demands on the medical, public health, and service sectors. • Their needs are complex and not adequately met through existing services and financing mechanisms. Given these criteria, additional groups might be considered vulnerable: veterans returning from combat duty, victims of natural disasters, prisoners, migrant workers, pregnant teenagers, and the uninsured or underinsured. See Box 19-1 for a list of potential vulnerable groups of people. Vulnerable populations are at increased risk for disease because of the interplay of the risk factors they face. If the woman described above has not received education regarding early detection, is homeless, and is uninsured with no regular source of health care, her risk for advanced breast cancer increases. Vulnerable populations are especially prone to these cumulative risks. Shi and Stevens (2005) describe these additional risks as not just adding to the probability of disease but multiplying the probability of becoming ill. As Rogers (1997) states, those who have a combination of high-risk factors are the most vulnerable. Healthy People 2020 graphically depicts how these internal and external factors interplay to determine the health of individuals (Figure 19-1). For example, discriminatory policies, substandard health care, lack of access to health care, environmental pollution, unsafe occupations, poverty, lack of social support, lack of education, unhealthy behaviors, and other factors can all be accommodated by the model. Relative risk is a ratio used in epidemiology to compare the risk for poor health among groups exposed to a risk factor versus those who are not exposed. Some will get the disease, and others will be more resilient and remain healthy. Members of vulnerable groups have been shown to have higher rates of disease than others and to have worse health outcomes. Perhaps their nutrition is not as good, or they are sleep deprived from working two jobs, or they have significant depression and fail to seek medical care. As a result, they are exposed to more risks and are likely to suffer more from a given risk than the general public. Flaskerud and Winslow (1998) say that a lack of resources increases relative risk, reduces the ability to avoid risks, and reduces the capacity to minimize any disease that may result. Some may ask, “Why do these individuals not protect themselves better and make better choices?” Some studies on vulnerability examine personal factors that contribute to vulnerability (Lessick, Woodring, Naber, & Halstead, 1992; Rogers, 1997), but there are also very influential social factors involved. These are called the social determinants of health. They are defined as “the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age, as well as the systems put in place to deal with illness. These circumstances are in turn shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, and politics.” (World Health Organization, 2010). Social determinants of health can be divided into three main categories: • Social institutions—for example, cultural and educational institutions, religious institutions, economic systems, political structures • Surroundings—for example, neighborhoods, housing, workplaces, towns and cities • Social relationships—for example, position in social hierarchy, social networks, differential treatment of social groups Geiger (2006) also lists income levels, rates of employment, educational opportunities, workplace safety, safe water, nutritious food, clean air, good sanitation, and uncontaminated soil as important factors. See Box 19-2 for some examples of social determinants of health.

Vulnerable Populations

![]() Key Concepts

Key Concepts

DEFINITION OF VULNERABILITY

VULNERABILITY

RISK, CUMULATIVE RISK, AND RELATIVE RISK

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Vulnerable Populations

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access