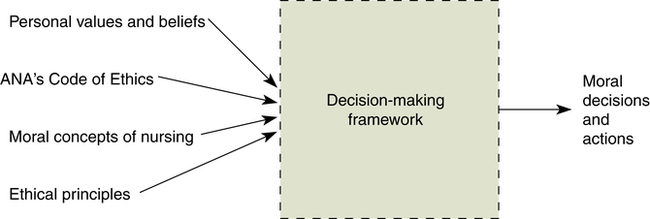

Heather Vallent, RN, MS and Pamela J. Grace, PhD, APRN At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the foundations of ethical nursing practice. • Identify the ethical content of everyday practice situations. • Analyze difficult practice and health care problems using a moral reasoning framework. • Use appropriate strategies and resources to address practice problems. • Delineate the scope of nursing’s responsibilities for ethical care environments. Moral philosophy is the pursuit of understanding human values (doing ethics). So what are values? Values are a way to qualify an action. Morally good choices must be supported by good reasons and must take into consideration other individuals, with impartiality (Rachels, 2007). Many philosophers have dedicated their life to defining the complexities of moral theory. Some variations include deontology, the concept that we should act according to a perceived duty, and utilitarianism, the idea that we ought to maximize the greatest good for the greatest number. Such theories arose out of the needs and struggles of particular eras and as such are useful to varying degrees in general life. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss the complexities of such theories. The various moral theories do provide some structure and perspective regarding the underlying concern; however, they are complicated and all are to some degree flawed or have been criticized as such. For this reason, in health care settings, we do not rely on any one moral theory to give us answers to a problem. As Grace (2009) states, “We must understand the limits of the theory and what its flaws are, rather than uncritically relying on theories to answer difficult issues in health care” (p. 13). Applied ethics is the application of the thoughts determined by moral reasoning. It is not enough to know what is good and what is the right thing to do; the ethical person needs to be able to act on his or her thoughts. This is often not an easy thing to accomplish. There are many people in this world, all of whom have a position on what they consider the right thing to do. One individual’s version can easily conflict with another’s: “Similarly, there is no reason to think that if there is moral truth everyone must know it” (Rachels, 2007, p. 11). Furthermore, what about the possibility that not all people are even capable of moral reasoning? To explore nursing ethics more specifically and to distinguish nursing ethics from health care ethics or medical ethics, we need to understand the professional goals of nursing and how these relate to promoting individual and societal good. According to Nightingale, nursing “ought to signify the proper use of fresh water, light, warmth … all at the least expense of vital power to the patient” (1969, p. 8). The means to this goal is complex; a nurse utilizes his or her own knowledge base, experience, personal limitations, a general understanding of ethics, and many other attributes to promote the good for the patient. Furthermore, “it is the discipline’s explicit aim of contributing both to the health of individuals and the overall health of society that makes nursing itself a moral endeavor” (Grace, 2009, pp. 52-53). We can think of nursing ethics in two different ways—a form of study that looks at nurses’ responsibilities or nurses’ actual practice of doing good (Grace, 2009). In Fry (2002), the main concerns for nursing ethics are the ability to describe the characteristics of the “good” nurse and to identify nurses’ ethical practices. From this we can deduce that the idea of the ethical nurse is one who can or does recognize a potential problem that must be differentiated as morally right or morally wrong. This struggle between right and wrong is often convoluted by the fact that rarely is one option completely right and another completely wrong; instead, we experience the inevitable gray area. For example, Mike, who lives with his family in a small but well-populated town, has tuberculosis, a highly contagious respiratory disease. Within the town, there is only one small hospital. Unfortunately, all of the hospital beds are currently occupied with very sick townspeople. Should Mike be admitted to the hospital, where he could be isolated to prevent him from spreading TB to his family, but thereby causing one of the very sick townspeople to be discharged prematurely from the hospital? Or should Mike stay at home with his family without precautions, thus exposing his family members to serious illness, but not displacing any current patients in the hospital? What would a “good” nurse do in this situation? Does a straightforward answer to this question even exist? To further expand on this thought, consider that the patient may not represent one individual, but rather a family or even a whole community or society at large. In moral reasoning, when neither option is ideal, the resulting gray area is called a dilemma. Abma and colleagues (2008) have reviewed multiple approaches to defining the characteristics of the “good” nurse or “good” care. From their research they have summarized that the concept of the “good nurse” is an outcome of a nurse’s reflective inner dialogue with other nurses and health care members, as well as with patients (i.e., “thinking through” a hypothetical conversation between oneself and others). They found that nurses, by engaging in these dialogues, “develop richer understandings of their practice” (Abma et al., 2008, p. 790). They postulate that if nurses are allowed the time for this reflective inner dialogue, then the attributes of a “good nurse” will develop over time, growing with each experience encountered and improving practice. Embodying these characteristics, a morally good nurse would be able to identify a problem, to articulate why it is a problem, to determine how a nurse would be affected by this problem, and to determine how the patient would be affected by this problem. Presumably, this would be followed by good action. For the good nurse to be able to identify all of these issues, a framework or a body of knowledge is required that can help the nurse decipher and process the problem. A nurse’s knowledge base is broad and draws on theories and evidence from a multitude of disciplines. This knowledge is filtered through the nursing perspective as developed over time by nursing’s scholars and clinicians. Nursing’s perspective is that human beings are unique, complex, and contextual. This perspective plus the goals of the profession related to facilitating health and relieving suffering provide a framework that allows us to appraise nursing actions. Nursing actions, then, are ethical if they use knowledge and skills to provide good nursing care, This precedent then essentially becomes a moral responsibility for the nurse to expand upon nursing’s goals of practice not only in individual situations but also in the interest of good practice as a whole (Grace, 2009). That is, good (ethical) nursing actions include addressing the source of obstacles to good practice that may arise from any levels of the health care system. Historically, nursing ethics was more concerned with the nurse’s personal behavior or virtues instead of his or her professional behavior (Fowler, 1997). An ethical nurse was one who was obedient and followed orders (Fry, 2002). According to Fowler (1997), in the late 1960s, nursing ethics evolved, along with general changes in society, to a more duty-based ethics, in which nurses were held accountable for their actions. However, Fowler argued that nursing ethics should be a combination of virtue-based and duty-based ethics; that is, nurses should be concerned not only with their actions, but also with the environment in which they practice. With this new sense of accountability, nursing needed guidelines from which to demonstrate ethical care. This concept of needing a code upon which to base nursing actions started in Detroit, Michigan, in 1893 with Lystra Gretter, who wrote the Nightingale Pledge. In 1896, a group of nurses formed an organization that later came to be known as the American Nurses Association (ANA). The group began the process of developing a code of ethics for nursing at that time, although the ANA did not formally accept a code until 1950. Since then, there have been several published revisions; the latest, Code of Ethics for Nurse with Interpretive Statements, was released in 2001 (Box 12-1). The International Council of Nurses (ICN), a federation of national nurses’ associations serving nurses in more than 128 countries, also published a code of ethics in 1953, with its most recent revision appearing in 2006 (ICN, 2006). Any code of ethics is established to protect the population it serves and to uphold the goals of the profession. Although many health care professions have similar goals, the perspective on how these goals can be met and the context in which the individual professions practice lead to profession-specific codes of ethics. The nursing profession has identified with the practice of ethics for years. As Fowler (1997) stated, ethics “has been the very foundation of nursing practice since the inception of modern nursing in the United States in the late 1870s” (p. 17). Implicit in the idea of having a Code of Ethics (2001) is the understanding that all actions of the individual nurse reflect on the actions of the nursing profession as a whole; therefore all actions should be congruent within the context of the Code. If any action by the nurse does not allow for the goals of the Code (Principle 1), then it is nursing’s obligation to fix this (Principle 10). It is in the best interest of nursing students to familiarize themselves with the Code and to reflect on its statements throughout their years of practice. Before discussing nursing’s research on ethics, it is necessary to review the historical aspects of the ethics surrounding research on human subjects. It is important to understand that all research is subject to ethical scrutiny. For a brief history of research ethics and human subject protection, refer to Box 12-2. Only by reviewing this history can one comprehend the growth that has occurred in this field. The concept of ethics in research has evolved over time with the change in nursing’s responsibilities, as discussed in the history of nursing ethics. In the early 1900s, the aim of studying nursing ethics was to gain clarity on nurses’ behavior and conduct in caring for the sick (Fry, 2002). After World War II, more nurses attended college and became more independent and accountable for their own clinical judgment (Grace, 2009). By the 1990s the topics explored by nurses had increased; however, Tschudin (2006), who served as editor of Nursing Ethics since its inception in 1994 until 2008, undertook a content review of the articles published over the first 10 years. She noted that initially the articles were “timid” and not particularly in-depth, but rather focused more on facts or legal issues without taking a stance on the issue. However, by 2003, many articles emphasized care and virtue ethics influenced by an intuitive response and with an affirmation of their beliefs. Some similarities throughout the 10 years of publication included the analysis of end-of-life care, nursing education, morality, moral decision making, and carrying out research (Tschudin, 2006). Contemporary nursing ethics analyzes nursing’s ability to meet the profession’s established goals. More emphasis is placed on virtue ethics and the intuitive process, rather than conduct and laws: “Nursing ethics remains a subject that will change and grow with what is given and taken, tried and not tried, and used or not used” (Tschudin, 2006, p. 74). Studies have shown that nurses sometimes do not understand that ethics is infused throughout all of their professional activities. For example, from an extensive survey (N = 2090) of nurses in the New England region who were asked about ethical issues encountered in practice, a small but significant proportion responded that they either never encountered ethical issues in the course of their work or that they rarely did (Grace, Fry, & Schultz, 2003). Additionally, in a research study that the authors of this chapter conducted related to understanding what experienced nurses see as essential characteristics of good nurses, some interesting themes are emerging as data are analyzed. This qualitative phenomenological study provides some tentative support for the idea that good nurses take all of their nursing role–related activities to be ethical in nature. Nurses who were not deemed “good nurses” by the respondents tended to focus on completing the day’s tasks in a timely manner rather than being responsible for their patients’ individual needs. Developing a nurse-patient relationship, when this is possible, tends to weaken the task-orientation of nurses and strengthens the focus on providing good care. This focus on the interests of the particular individual and his or her unique needs has long been considered part of the nurse’s caring function. The nurse-patient relationship, like the physician-patient relationship, has been described as fiduciary in nature (Grace, 1998, 2009; Spenceley, Reutter, & Allen, 2006; Zaner, 1991). What this means is that the person who presents to us in need of health care is vulnerable as a result of their needs. They are relying on us to work toward meeting their needs and are counting on us not to be distracted by other issues. They are hoping, if not expecting, that their interest remains our most important concern. This places a heavy burden on nurses who often practice within institutions and settings that limit their actions. Many nurses see this as too much to ask. Any number of things might influence their ability to do best for a given patient. Consider a few examples: staffing is poor, and the nurse is forced to juggle the care needs of several very critical patients; the institution is trying to cut costs and does not have the best drug or the most effective monitoring equipment for the patient; changes in health care system financing lead to shorter lengths of stay (LOS), and patients are often released home before they are ready; a frail, elderly patient is sent home with no capable adult available to provide the needed care. In addition to institutional constraints on good care, the nurse may be experiencing difficulties in his or her personal life, may be emotionally or physically exhausted, or may be suffering from residual “moral distress.” First described by Jameton (1984) and later studied by other scholars (Corley, 2002; Corley, Minnick, Elswick, & Jacobs, 2005; Eizenberg, Desivilya, & Hirschfeld, 2009; Mohr & Mahon, 1996), moral distress is a feeling of unease that accompanies the inability to do what one knows to be right. Left unaddressed, moral distress can have long-lasting effects on people and has been shown to cause nurses to leave nursing. Nurses who remain may distance themselves from and cease to engage with patients. Both of these actions, leaving nursing and failing to interact with patients, are thought to be defense mechanisms that nurses have used to cope with moral distress. Here are some common examples of situations that can lead to a nurse’s distress: the seemingly uncaring attitudes of one’s colleagues, physicians who do not listen to a nurse’s account of what the patient wants, families who disagree about what treatments a patient should have, and so on. Although nurses sometimes feel powerless to do the right thing under difficult conditions, there are appropriate and effective paths of recourse. Learning how to evaluate complex issues and analyze aspects of difficult cases with personal reflection and dialoguing with others (Abma et al., 2008) is one way to come to terms with and diffuse moral distress. Taking action to remedy a problem is a further way to disperse residual feelings of moral distress. However, before appropriate action can be identified and taken, we must understand our professional obligations as nurses. The ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001) has clearly articulated the professional obligations for nurses in the United States. These obligations are all rooted in the goals that nursing as a profession has determined over time by nursing scholars and practicing nurses. The goals are concisely articulated in the ANA’s Social Policy Statement (2003): What is a decision-making tool? It is a helpful framework or structure for working through a difficult problem. Figure 12-1 is a schematic approach to visualize the many elements that are involved in moral decision making. There are many decision making frameworks available in both nursing and ethics textbooks. The one used in this chapter is synthesized by one of the authors (Grace) from her clinical and educational experiences and the extant literature, and it is presented later in the chapter. Ethical principles are “rules, standards, or guidelines for action that are derived from theoretical propositions … about what is good for humans” (Grace, 2009, p. 17). More simply put, they are statements that capture what humans have over time come to believe is important in ensuring a reasonably good life for individuals living within mutually beneficial societies. Societies are, of course, made up of individuals who work together to meet collective needs. No one person is capable of solely providing for his or her own needs. Ethical principles have their roots in different philosophical points of view, but historically they have come to be seen as useful for “imposing order on a situation, highlighting important considerations in problem-solving complex issues” (Grace, 2009, p.17) and holding people accountable for their treatment of others. They are reflective of cultural, religious, and social values, and thus different cultures may stress certain principles over others. Ethical principles themselves, many of which derive from moral theory, have proven useful in providing clarity and in bringing out underlying assumptions that are being made in a situation. For example, in the Western world, autonomy is often viewed as the most important principle, whereas in other cultures social harmony may be seen as more important than an individual’s right to make his or her own decisions. This next section discusses the four principles (beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, and autonomy) that Beauchamp and Childress (2008) highlighted, as well as some other concepts that have been seen as important in enabling good nursing practice. Ethical principles serve as a “beginning or starting point for reasoning” (Thompson, Melia, & Boyd, 2000, p. 13). They are not absolutes. That is, no one principle will lead to the right action in every circumstance, because they are derived from a variety of ethical theories and perspectives over time. Consequently, principles that have proven helpful to ethical reasoning in health care settings can conflict with each other. It is important to keep this in mind because we may have to choose which principle to favor in a given situation. This decision most often will depend on the particular situation and the goals for the main focus of the decision making—most often an individual patient. Ethical principles, however, are helpful in providing clarity about the salient issues to consider in a problematic situation. They trigger more questions and permit the revelation of underlying assumptions. Thus ethical principles are the most helpful in the analysis phase of the problem-solving process. They help determine the most critical issues, such as what is at stake and for whom. Beauchamp & Childress (2008) have stated that ethical principles are action guides to moral decision making and are an important element in the formation of moral judgments in professional practice. For nurses, our overriding action guide is the “good” of the patient in front of us. This idea is captured by the principle of beneficence. Beneficence is the obligation to provide a good. When nurses enter the profession and start to practice, they are essentially promising that they can provide a good. If there were no benefit that nurses could bring to patients, there would be no need for nurses. In broader terms, beneficence means that not only are we as nurses obliged to provide a good, but we are charged with avoiding harm as a byproduct of our good actions. In health care ethics language, acting on this principle means helping others to gain what is of benefit to them. However, in order to do this, we must understand what benefit means in terms of others’ (patients’) desires and needs. The obligations of beneficence, then, are stronger for the nurse when acting as a nurse than when acting as a citizen in everyday life. This is because the purposes and goals of nursing are explicitly to provide for the patient’s good. The ANA’s Social Policy Statement affirms nursing’s commitment to provide “safe, effective, quality care” (ANA, 2003, p. 1). The goals of nursing are generally understood to be “the prevention of illness, the alleviation of suffering, and the protection, promotion, and restoration of health” (ANA, 2001, p. 5). All of these services are “goods” because they address critical human needs; thus the goals of nursing are beneficent goals. Applying the principle of beneficence in nursing practice, though, may not be as simple as it sounds. For example, is the nurse obliged to consider all the ways in which the patient might be benefited? What should the nurse do if obstacles exist to giving good care that are beyond his or her immediate control? A second problem in applying this principle is deciding whether the obligation to provide benefit is stronger than the obligation to avoid harm. Some ethicists claim that the duty to avoid harm—also known as the ethical principle of nonmaleficence—is a stronger obligation (at least in contemporary health care relationships) than the obligation to benefit (Beauchamp & Childress, 2008). This opinion has risen, in part, because we now have powerful biological and technological advances that can be used to treat or save critically ill patients, but these tools can also have extreme side effects. Another consideration in ethical decision making is how benefits and burdens should be distributed among patient populations (Fry & Veatch, 2006). Nurses generally care for several patients during any given shift. A decision may have to be made about what is a just or fair allocation of resources among patients under the nurse’s care. Should the priority be based on the greatest need, the sickest patient, or the patient most likely to recover? In addition, nurses are also often faced with the end results of unjust social arrangements. In the United States, we see quite often very sick patients who do not have easy access to, or cannot afford, preventive health care or health-promoting care. This puts these patients at a disadvantage in many ways and causes harm in the sense that they do not seek care early in their illness. Consequently, these patients’ illnesses may likely become more severe and result in irreversible damage. The principle of justice is likely to lead nursing to work towards change. Both the ANA’s Code of Ethics (2001) and the ANA’s Social Policy Statement (2003) highlight the nurse’s responsibility to join with others and address inequities at the institutional and societal level. In A Theory of Justice, Rawls (1971) hypothesizes that those who are the least advantaged in terms of possessing material goods and/or personal abilities should receive the most benefit from social structures that serve the public. When this does not happen, Rawls argues, nurses and other health care providers who see first-hand the results of these inequities have a responsibility to act to change the situation. A further discussion of health care disparities occurs in Chapters 14 and 19. Currently, health care arrangements in the United States cannot be described as just, because many individuals are uninsured and have inadequate access to health care. The U.S. Census Bureau, in 2007, estimated that more than 45 million Americans were without health insurance (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2008). Nurses are among those who are the most likely to see the effects of poor health monitoring and maintenance on the severity of their patients’ illnesses. Nurses thus have responsibilities for social and political activism related to ensuring just health care. Provision 8 of the ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001) delineates nursing’s responsibilities to be collectively active in promoting societal health (see Box 12-1). Socioeconomic factors and roles of the professional nurse are also addressed in Chapters 7 and 4, respectively.

Ethical Dimensions of Nursing and Health Care

![]() Foundations of Ethical Nursing Practice

Foundations of Ethical Nursing Practice

MORAL PHILOSOPHY

APPLIED ETHICS

NURSING ETHICS

Nursing Ethics History

Nursing Ethics Professional Values

Research on Nursing Ethics

![]() Ethical Nursing Practice

Ethical Nursing Practice

PERCEIVING ETHICAL CONTENT

Decision-Making Tools

What Are Ethical Principles?

Beneficence

Justice

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethical Dimensions of Nursing and Health Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access