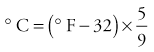

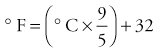

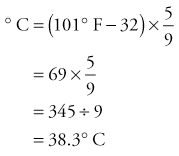

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills while performing patient assessment and patient care. 4. Describe emotional and physical factors that can cause the body temperature to rise or fall. 5. Convert temperature readings between the Fahrenheit and Celsius scales. 6. Obtain and record an accurate patient temperature using three different types of thermometers. 7. Describe pulse rate, rhythm, and volume. 8. Locate and record the pulse at multiple sites. 9. Demonstrate the best way to obtain an accurate respiratory count. 10. Specify physiologic factors that affect blood pressure. 11. Differentiate between essential and secondary hypertension. 12. Interpret revised hypertension guidelines and treatment. 13. Identify the different Korotkoff phases. 14. Accurately measure and document blood pressure. 15. Accurately measure and document height and weight. 16. Convert kilograms to pounds and pounds to kilograms. 17. Identify patient education opportunities when measuring vital signs. 18. Determine the medical assistant’s legal and ethical responsibilities in obtaining vital signs. apnea (ap′-nee-uh) Absence or cessation of breathing. arrhythmia An abnormality or irregularity in the heart rhythm. arteriosclerosis (ar-ter′-ee-o-scler-o-sis) Thickening, decreased elasticity, and calcification of arterial walls. bradycardia (brad-i-kahr′-dee-uh) A slow heartbeat; a pulse below 60 beats per minute. bradypnea (brad-ip-nee′-uh) Respirations that are regular in rhythm but slower than normal in rate. cerumen (see-room′-men) A waxy secretion in the ear canal; commonly called ear wax. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) A progressive, irreversible lung condition that results in diminished lung capacity. diurnal (die-ur′-nl) rhythm Pattern of activity or behavior that follows a day-night cycle. dyspnea (disp-nee′-uh) Difficult or painful breathing. essential hypertension Elevated blood pressure of unknown cause that develops for no apparent reason; sometimes called primary hypertension. febrile (feb′-ril) Pertaining to an elevated body temperature. hyperpnea (hahy-per-nee′-uh) An increase in the depth of breathing. hypertension High blood pressure. hyperventilation Abnormally prolonged and deep breathing, usually associated with acute anxiety or emotional tension. intermittent pulse A pulse in which beats occasionally are skipped. orthopnea (or-thop′-nee-uh) Condition in which an individual must sit or stand to breathe comfortably. orthostatic (postural) hypotension A temporary fall in blood pressure when a person rapidly changes from a recumbent position to a standing position. otitis externa Inflammation or infection of the external auditory canal (swimmer’s ear). peripheral (puh-rif′-er-uhl) Term that refers to an area outside of or away from an organ or structure. pulse deficit Condition in which the radial pulse is less than the apical pulse; may indicate a peripheral vascular abnormality. pulse pressure The difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressures (30 to 50 mm Hg is considered normal). pyrexia (pi-rek′-see-uh) Febrile condition or fever. rales Abnormal or crackling breath sounds during inspiration. rhonchi (ron′-ki) Abnormal rumbling sounds on expiration that indicate airway obstruction by thick secretions or spasms. secondary hypertension Elevated blood pressure resulting from another condition, typically kidney disease. sinus arrhythmia Irregular heartbeat that originates in the sinoatrial node (pacemaker). spirometer Instrument that measures the volume of air inhaled and exhaled. stertorous (stuh-tuh′-rus) Term that describes a strenuous respiratory effort marked by a snoring sound. syncope (sing′-kuh-pee) Fainting; a brief lapse in consciousness. tachycardia (tak-i-kahr′-dee-uh) A rapid but regular heart rate; one that exceeds 100 beats per minute. tachypnea (tak-ip-nee′-uh) Condition marked by rapid, shallow respirations. thready Term that describes a pulse that is scarcely perceptible. Dr. Susan Xu is a member of a multiphysician primary care practice. Each physician in the practice has a medical assistant who works directly with him or her. Carlos Ricci, CMA (AAMA), is Dr. Xu’s assistant. Carlos graduated from a medical assistant program 3 years ago and enjoys the variety of patients seen in Dr. Xu’s practice. One of Carlos’ primary responsibilities is to accurately measure and record each patient’s vital signs before the patient is seen by Dr. Xu. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: Measurement of vital signs is an important aspect of almost every patient visit to the medical office. These signs are the human body’s indicators of internal homeostasis and the patient’s general state of health. Because medical assistants are chiefly responsible for obtaining these measurements, it is imperative that they have confidence in the theoretic and practical applications of vital sign measurement. A medical assistant who understands the principles of and the reasons for these measurements becomes a valuable asset to any medical office. Accuracy is essential. A change in one or more of the patient’s vital signs may indicate a change in general health. Variations may suggest the presence or disappearance of a disease process and therefore may lead to alteration of the treatment plan. Although the medical assistant obtains vital signs routinely, it is a task that requires consistent attention to accuracy and detail. These findings are crucial to a correct diagnosis, and vital signs should never be measured with indifference or casualness. In addition to performing accurate measurement, care must be taken when charting the findings on the patient’s medical record. Vital signs are the patient’s temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure. These four signs are abbreviated TPR and BP and may be referred to as cardinal signs. The medical assistant must understand the significance of the vital signs and must measure and record them accurately. Anthropometric measurements are not considered vital signs but usually are obtained at the same time as vital signs. These measurements include height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and other body measurements, such as fat composition and an infant’s head circumference. Vital signs are influenced by many factors, both physical and emotional. A patient may have drunk a hot or cold beverage just before the examination or may be angry or fearful about what the physician may find. For example, consider that a patient has been asked to return to have a repeat Papanicolaou (Pap) smear because the first one showed the presence of suspicious cells. The medical assistant measures the patient’s blood pressure and finds it significantly elevated compared with previous readings. The patient may be anxious and apprehensive about the test results, and the elevated blood pressure readings reflect her anxiety. What temperature reading might be expected in a patient who could not find a parking place and had to walk four blocks to the office, knowing he would be late for his appointment? If you said it would be elevated, you are right. Certainly, this patient’s metabolism would increase because of the physical exercise, and as a result, his temperature would be elevated, along with his pulse, respirations, and blood pressure. For one reason or another, many patients are apprehensive during an office visit. These emotions may alter vital signs, and the medical assistant must help the patient relax before taking any readings. Measurements sometimes must be obtained a second time, after the patient is calmer or more comfortable. For a better picture of the patient’s vital signs, the medical assistant may be asked to record the vital signs twice: at the beginning of the visit and just before the patient leaves the office. Body temperature is defined as the balance between heat lost and heat produced by the body. It is measured in degrees Fahrenheit (F) or degrees Celsius (C). The process of chemical and physical change in the body that produces heat is called metabolism. Body temperature is a result of this process. The core body temperature is maintained within a normal range by the thermoregulatory center in the hypothalamus. The average body temperature varies from person to person and is different in each person at different times throughout the day. In a healthy adult, this diurnal rhythm varies from 97.6° F to 99° F (36.4° C to 37.3° C); the average daily temperature is 98.6° F (36.8° C). Body temperature is lowest in the morning and highest in the late afternoon. Factors that may affect body temperature include the following: In illness, an individual’s metabolic activity is increased; this causes an increase in internal heat production, which in turn raises the body temperature. The increase in body temperature is thought to be the body’s defensive reaction because heat inhibits the growth of some bacteria and viruses. When a fever is present, superficial blood vessels (those near the surface of the skin) constrict. The small papillary muscles at the base of hair follicles also constrict, creating goose bumps. Chills and shivering may follow, producing internal heat. As this process repeats itself, more heat is produced, and the body temperature becomes elevated or rises above the normal range. When more heat is lost than is produced, the opposite effect occurs, and body temperature drops below normal range. Infection, either bacterial or viral, is the most common cause of fever in both children and adults. Infants do not usually develop febrile illnesses during the first 3 months of life; if one is present, it usually is very serious. However, fever, or pyrexia, is very common in young children and accounts for an estimated 26% of office visits. Fevers are classified according to the 24-hour pattern they follow. The three most common patterns are: Variation from the patient’s average body temperature range may be the first warning of an illness or a change in the patient’s current condition. Patients with fever usually have loss of appetite (anorexia), headache, thirst, flushed face, hot skin, and general malaise. Some patients experience an acute onset of chills and shivering followed by an increase in body temperature. A serious possible complication in young children with high fevers is a febrile seizure. Medication to reduce the fever, or antipyretic drugs (e.g., Tylenol), should be taken as instructed to prevent dangerous spikes in temperature. Age-related normal values for temperature readings are shown in Table 31-1. TABLE 31-1 A clinical thermometer is used to measure body temperature. It is calibrated in the Fahrenheit or the Celsius scale. The Fahrenheit scale is used most often in the United States, but hospitals and many ambulatory care settings use the Celsius scale. The formulas for conversion from one system to the other are as follows: For example, if an infant’s temperature is measured at 101° F, the Celsius conversion would be: If the ambulatory care setting where you work uses a Celsius thermometer, patients may ask you what the temperature is in Fahrenheit degrees because that is the scale they understand. If the facility does not have a conversion chart available, you will need to convert the temperature mathematically. For example, if an infant’s temperature is 39° C, what is the Fahrenheit reading? Several types of thermometers and several different methods can be used to take temperature readings. A digital thermometer is placed under the tongue, in the armpit, or rectally; a tympanic thermometer is inserted into the ear; and a temporal artery scanner is moved across the forehead. Average temperature values for adults at the four most common sites are shown in Table 31-2. TABLE 31-2 Axillary temperatures are approximately 1° F (0.6° C) lower than accurate oral readings because axillary readings are not taken in an enclosed body cavity. When taken correctly, the tympanic (ear) temperature is an accurate measure because it records the temperature of the blood closest to the hypothalamus. However, recent research on the newest device for obtaining temperature, the temporal artery (TA) thermometer, indicates that this method is more accurate than tympanic measurement for identifying elevated temperatures in infants. Pediatricians, therefore, may prefer TA temperatures in infants suspected of having a fever. The TA thermometer also records accurate temperature readings in all age groups of patients. The tympanic method still is considered a fast, accurate, and noninvasive way of recording temperatures for older children and adults. When obtaining an oral temperature, you do not have to indicate the site when documenting the reading in the patient’s chart. However, you should write (T) for tympanic, (A) for axillary, or (TA) for temporal artery readings after recording the temperature to clarify that an alternative site was used. Oral temperature cannot be measured accurately in young children because the technique requires patients to hold the thermometer under the tongue and keep the mouth closed. To take an infant’s temperature rectally, lubricate the probe tip, hold the baby securely with the legs elevated, and insert the probe approximately ½ inch; hold the probe carefully throughout the procedure to prevent rectal damage. However, pediatricians may prefer that infants’ temperatures be taken with a temporal thermometer because it is more comfortable for the baby, is less invasive, and eliminates the possible complication of a perforated rectum. For patients older than 3 years and for those unable to hold a thermometer properly in their mouth during the procedure, a tympanic or temporal thermometer can be used; if not, a less accurate axillary temperature can be obtained. Digital thermometers are battery operated and are available in both Fahrenheit and Celsius scales. Disposable covers fit snugly over the probes and are easily and quickly removed by pushing in the colored end of the probe. The instrument sounds a beep when the process is completed (10 to 60 seconds), and the reading appears on a light-emitting diode (LED) screen on the face of the instrument (Procedure 31-1). Because the only part of the instrument that comes in contact with the patient is the probe, which is sheathed, the risk of cross-infection is greatly reduced (Figure 31-1). Another type of digital thermometer resembles the old mercury thermometers that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) no longer allows clinicians to use in healthcare facilities. These thermometers have a digital screen on which the temperature is read and should always be covered by a disposable sheath. Temperature should not be taken orally if the patient recently has had something hot or cold to eat or drink or has just smoked, because these factors may artificially alter the patient’s temperature. In addition, the patient must be able to hold the thermometer under the tongue with the lips tightly sealed around the probe of an accurate oral reading is to be obtained. The tympanic membrane of the ear can be used for quick, accurate, and safe assessment of a patient’s temperature. It shares the blood supply that reaches the hypothalamus, which is the brain’s temperature regulator. The ear canal is a protected cavity, so aural temperature is not affected by factors such as an open mouth, hot or cold drinks, or even a stuffy nose, which would prevent a patient from keeping the mouth closed during the procedure. In addition, the covered probe is designed to bounce an infrared signal off the eardrum without touching it, so the risk of spreading communicable diseases during temperature measurement is greatly reduced. The tympanic measurement system consists of a handheld processor unit equipped with a tympanic probe, which is covered with a disposable speculum for use (Figure 31-2). When the probe is placed into the ear canal, it gently seals the external opening of the canal, and the infrared energy emitted by the tympanic membrane is gathered. This signal is digitized by the processor unit and is shown on the display screen. Accurate readings are obtained in less than 2 seconds (Procedure 31-2). Both the speed of the tympanic thermometer and the comfort it affords the patient have greatly influenced its popularity. However, this unit should not be used (1) if the patient has bilateral otitis externa, because the procedure would be uncomfortable for the patient, and (2) if impacted cerumen is present in both ears, because the reading may be inaccurate. The temporal artery scanner uses an infrared beam to assess the temperature of the blood flowing through the temporal artery of the lateral forehead, where the artery lies about 1 mm below the skin (Figure 31-3). Because the artery is so close to the skin, it provides good surface heat conduction, allowing the thermometer to obtain a fast, accurate, and noninvasive measurement of the body temperature. To perform the procedure, place the probe in the center of the forehead, halfway between the eyebrows and the hairline. Bangs should be pushed back off the forehead (this method cannot be used if bandages cover the area). Depress the button on the scanner and gently stroke the probe across the forehead toward the hairline (at the temples), keeping the probe flat on the patient’s skin. As the scanner moves across the forehead, repeated temperature measurements are taken and the highest measurement is recorded; keeping the button depressed, lift the scanner from the temporal area and lightly place the probe behind the earlobe. Release the button and remove the probe. Recording an accurate temperature takes about 3 seconds (Procedure 31-3). Studies indicate that axillary temperatures are accurate when performed correctly. Axillary temperatures take more time to register the correct body temperature, but the method is safe, simple, and easy to perform (Procedure 31-4). Axillary temperatures are taken with a digital thermometer, which is placed into the axillary fold. If the digital thermometer has more than one probe, the oral (blue) probe with a disposable probe cover should be used. Because tympanic and temporal thermometers are relatively expensive, the axillary method may be a viable way for parents of young children to get accurate temperature readings at home. However, parents should be aware that the axillary temperature may be as much as one degree less than the child’s actual core temperature.

Vital Signs

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Factors That May Influence Vital Signs

Temperature

Physiology

Fever

AGE

FAHRENHEIT

CELSIUS

Newborn (axillary)

98.2°

36.8°

1 year

99.7°

37.6°

6 years to adult (oral)

98.6°

37°

Elderly over age 70 (oral)

96.8°

36°

Temperature Readings

SITE

FAHRENHEIT

CELSIUS

Oral

98.6°

37°

Axillary

97.6°

36.4°

Tympanic

98.6°

37°

Temporal artery

98.6°

37°

Types of Thermometers and Their Uses

Digital Thermometer

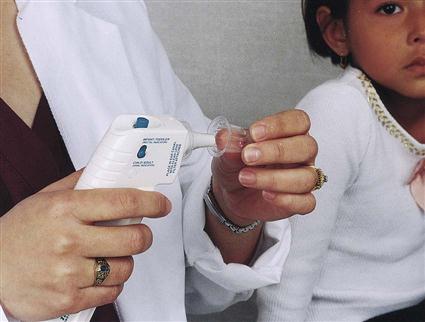

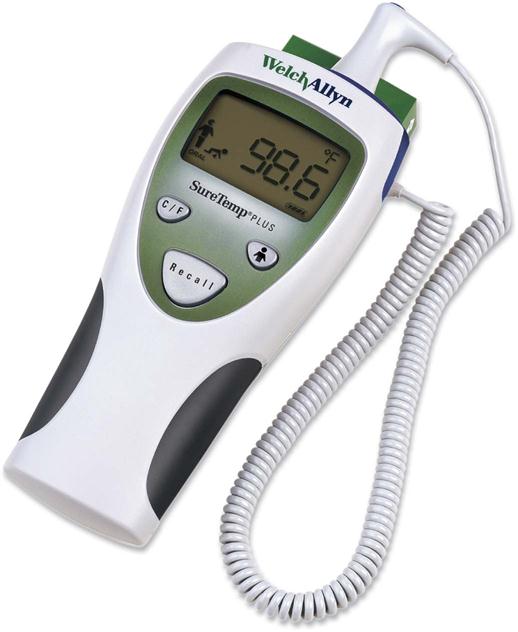

Tympanic Thermometer

Temporal Artery Scanner

Axillary Thermometer

Vital Signs

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access