Utilizing a Resource Nurse Model to Improve Nosocomial Pressure Ulcer Rates

Gale Danek PhD, RN, NE-BC1

Betty Jax MSN, ARNP, RN-BC2

Peggy Guin PhD, ARNP, CNRN, CNS-BC3

1Administrative Director, Nursing Research

danekg@shands.ufl.edu

2Administrative Director, Nursing Education

3Neuroscience Clinical Nurse Specialist

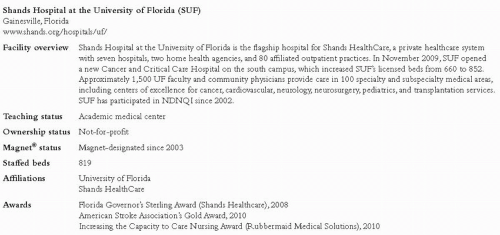

Shands Hospital at the University of Florida Gainesville, Florida www.shands.org/hospitals/uf/

Case Study Highlights

Unit staff nurses were trained as Ostomy Wound Liaison (OWL) resource nurses to serve as pressure ulcer prevention experts for their peers. OWLs collaborated with the hospital’s Pressure Ulcer Prevention (PUP) Team to implement product and process changes. Monthly prevalence studies facilitated immediate remedy of pressure ulcer causes. These strategies, characterized by team building and staff empowerment, led to sustained improvement in hospitalacquired pressure ulcer (HAPU) rates.

Pressure Ulcers in Highly Complex Patients

In early 2004, the Nursing Quality Council and nursing leadership at Shands Hospital at the University of Florida (SUF) recognized that the hospital lacked a reliable measure for assessing pressure ulcer issues. Although SUF has participated in NDNQI® since 2002 (see Figure 1), pressure ulcer data were not submitted until 2004. At this time, SUF committed to conducting quarterly pressure ulcer prevalence studies and submitting data to NDNQI. One of the driving forces for doing this was the confidence that NDNQI comparison data would provide accurate benchmarks for the hospital’s complex and high-acuity patient populations.

In 2004, adult intensive care and intermediate care patients made up 30% of the total beds and were the highest risk patients for pressure ulcer development. In the first quarter of 2004 (1Q04), SUF’s four adult intensive care units (ICUs) had an average HAPU prevalence of 23.8%, well above the NDNQI mean of 17.5% for ICUs in hospitals with over 500 beds.

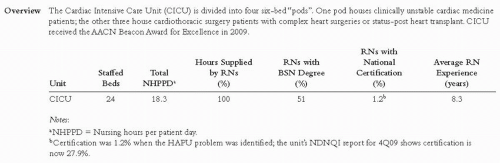

The cardiac intensive care unit (CICU), which cares for cardiac and cardiothoracic surgical patients (see Figure 2), had a much higher HAPU rate at 37.5%.

Many CICU patients have overall poor perfusion and are particularly prone to pressure damage. Cardiovascular surgery patients posed the highest risk. These patients had operating room times that frequently exceeded eight hours and many required extended use of cardiac bypass or aortic cross-clamp during surgery. CICU patients with dissecting aortic aneurysms virtually lost perfusion below the point of the dissection until surgical repair could be completed. Routine HAPU prevention strategies were more difficult to execute in CICU patients because of the presence of multiple IV/IA access devices or open chest cavities. As a result, the culture on the CICU prior to 2004 was somewhat resigned, as the staff viewed HAPUs as an unavoidable complication of that population.

Initial Response to High HAPU Rates

The initial HAPU reduction activities in 2004 and 2005 centered on understanding the issues and helping staff “own” the problem. Nursing leadership, particularly the Vice President of Nursing and the Administrative Director for Professional Practice, quickly identified several key issues contributing to HAPU prevalence. The hospital had very limited expert resources, specifically 1.5 full-time employees (FTEs) for Certified Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses (CWOCN) for 530 beds. There was also a lack of knowledge among all staff, lack of bedside expertise, lack of standardized protocols, ineffective utilization of Braden scores, equipment issues, and inadequate communication of timely HAPU prevalence data at the unit level.

NDNQI quarterly prevalence studies helped address several issues. The data collection process was standardized, staff became more aware of HAPUs, and valid benchmarking data allowed nursing leadership to set goals for the hospital and each unit. HAPUs became the first nursing-sensitive indicator fully embraced by unit level staff, nursing leadership, and senior administration. In late 2004, Shands Healthcare launched a system-wide Pressure Ulcer Prevention (PUP) Team initiative that served to solidify top administrative support and goal setting. Evidence-based skin care protocols were developed and extensive staff education was implemented. SUF’s PUP team was led by an administrative director and the CWOCN. By 4Q05, the average HAPU prevalence rates on the adult ICUs improved to 6.4%, with CICU dramatically reducing their rate to 4.7%.

The Resource Nurse Model

Although significant progress was made over the initial two years, nursing leadership realized in early 2006 that further efforts were required to consistently hold the gains from quarter to quarter. If staff were to own this nursing-sensitive indicator, a creative strategy was needed. Consistent with Magnet® philosophy and the SUF nursing vision of “autonomous, accountable nursing practice”, senior nursing leadership embraced the Ostomy Wound Liaison (OWL) resource nurse model to empower frontline nursing staff to improve their practice and patient outcomes.

The OWL resource nurse model had initially been piloted on a few ICUs in 2004. In 2006, six clinical nurse specialist (CNS) positions were implemented. The CNSs were involved in expanding the OWL program to all units, including critical care, medical-surgical, and pediatric areas. Along with the CWOCN, the new CNSs mentored the unit-based resource nurses.

Resource nurses, as defined by SUF leadership, are clinical experts who function as both a resource and a change agent by disseminating evidence-based information and interfacing with nurses, physicians, patients, and families. For staff nurses to become resources and change agents for their peers, they must receive advanced education, develop their clinical and interpersonal skills, and spend time practicing with clinical experts. To accomplish this, several strategies were established:

Basic OWL training consisting of a one-day education session with CWOCNs and experienced

OWLs and completion of NDNQI pressure ulcer online training

Rounds with experienced OWLs, CWOCNs, or CNSs

Participation in monthly prevalence studies, with CWOCNs or CNSs verifying all ulcers and ulcer staging to increase confidence in data accuracy

Clinical practicum with CWOCNs or experienced OWLs

One-day courses focusing on interpersonal skills and change strategies

Quarterly education meetings

Yearly Wound and Skin Continuing Education Days

Ongoing mentoring by CWOCNs and CNSs to help resource nurses synthesize information and operationalize their role at the bedside

Upon completion of the basic OWL training, new resource nurses receive the OWL recognition pin (see Figure 3). Designed jointly by the CWOCNs and OWLs, the pin enables colleagues to easily identify the resource nurses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree