Chapter 12 Using media in health promotion

Overview

Communication of information and advice is central to health promotion strategies. A knowledge of how communication between the sender and receiver of messages takes place and an understanding of the medium through which communication occurs are therefore important tools for the health promoter. Mass media is a powerful agent of communication, reaching large numbers of people. In addition to the traditional media (radio, television, press) new forms of media, most notably the internet, have changed communication patterns and coverage. The mass media now combines the capacity to reach large numbers of people with the capacity to be accessed individually as and when people choose. Mass media has a long history of persuading people to buy a vast array of products and lifestyles which create ill health, such as tobacco, alcohol and fast cars, through both paid advertising and current affairs coverage. Paid advertising and campaigns, unpaid news coverage, social marketing and media advocacy are all used to promote health. Practitioners also use posters, leaflets and other tools to enhance communication with service users. This chapter looks at the potential and limitations of using various media in these different ways to promote health. Readers can find a more detailed discussion of health communication and social marketing in Chapter 8 of our companion volume (Naidoo & Wills 2005).

Introduction

The first 10 years of our existence could well be called the era of propaganda. Health education has been realised mainly in terms of mass publicity on all fronts. Ad hoc exhortations have been directed at the public following closely the patterns of commercial advertising (Burton, cited in Tones 1993, p. 128).

Many [have come] to feel that mass publicity methods were expensive and relatively ineffective in changing people’s health habits and beliefs, and that health education would have to be planned on a more personal basis (Burton, cited in Tones 1993, p. 128).

The relationship between the media and the public is complex. In addition to its primary function of informing and entertaining, the media plays a pivotal role in social cohesion, defining what is normal and desirable, and what is not. McQuail (2005) identifies several different roles played by the media:

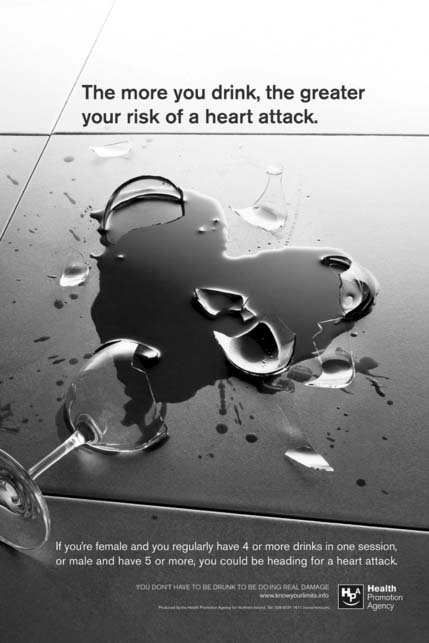

The mass media is important to health promotion because it is so widely used. Many public health issues, e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), alcohol misuse and smoking have been the subject of extensive mass-media campaigns. The aim of such campaigns is usually to raise awareness or present a message advocating healthy lifestyles (Figure 12.1). Beattie (1993) describes the use of the media as ‘health persuasion’, by which he means a top-down conservative method designed to infuse an audience with information.

The media may also be an unhealthy influence, advertising unhealthy products, e.g. fast food, or transmitting unhealthy messages, e.g. that drinking excessively is fun and fashionable. The media also plays a major role in constructing society’s views on health issues and services. What health issues are covered, and the slant the reporting takes, are powerful forces in public discourse around health.

The nature of media effects

The mass media is a distinctive form of communication with specific properties, including:

These characteristics include both strengths and weaknesses when the aim is to promote health. Although a mass audience is guaranteed, with favourable cost implications, ‘correct’ reading, understanding and recall of the intended message by the target audience is by no means certain. A great deal of research is needed to develop suitable messages that will appeal to the target audience and to evaluate their real-life impact. Chapter 8 in our companion volume (Naidoo & Wills 2005) discusses the nature of health promotion messages.

Views on the effects of the mass media have shifted from an early belief that the mass media could produce dramatic changes in attitudes and behaviour to the opposite view that the media has negligible effects (Gatherer et al 1979). Today there is a more tempered view, which regards the media as influential in certain circumstances and in specific ways. For example, a recent systematic review concluded that the use of mass media in promoting the use of health services was effective (Grilli et al 2002). The West Yorkshire Smoking and Health Trial (McVey & Stapleton 2000) demonstrated that a prolonged, heavy-weight, well-resourced mass media campaign can contribute to a significant reduction in smoking prevalence.

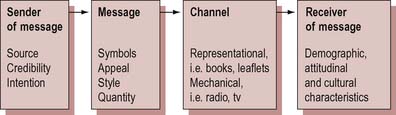

Lasswell (1948) presents the following model of mass communication:

Lasswell’s model is useful in flagging up all the key stages of the process of mass communication:

This model was developed with traditional forms of mass media in mind, and its applicability to newer forms of instant and overlapping communication and technologies has been questioned (Chamberlain 1996). The new technologies, such as text messaging or social network sites, are particularly relevant if young people are the target group. Young people are media-literate, i.e. they can access, understand and create communications using a variety of new technologies, including the internet and mobile phones. These new forms of communication may be used to promote health. Text messaging has been successfully used to improve self-management of diabetes (Franklin et al 2006), and has also been used to engage young people in health messages (Dobkin et al 2007). Atkin (2001) has argued that the new interactive and individually tailored communication technologies empower users. Benefits of these new means of communication include relative anonymity, avoidance of stigmatization and marginalization and immediate access wherever people are.

Four main models of how the media affects audiences have been suggested:

Direct effects (linear causal)

This model likens the effects of the mass media to a hypodermic syringe that has an immediate and direct effect on its audience. It assumes a passive audience which can be swayed by manipulative mass media. This view prompted the development of political broadcasts intended to shift voting intentions.

In 1938 Orson Welles broadcast a radio version of H G Wells’ classic science fiction story The War of the Worlds. Thousands of American listeners assumed that the story of an imminent alien invasion from outer space was real and panic spread as people started to flee (Cantril 1958).

This view has since been replaced by an aerosol spray analogy:

Rather than being a hypodermic needle, we now begin to look at mass communication as a sort of aerosol spray. As you spray it on the surface, some of it hits the target: most of it drifts away; and very little of it penetrates (Mendelsohn 1968).

Two-Step or diffusion of innovation model

This model suggests that mass communication influences key opinion leaders who are active members of the mass-media audience. These opinion leaders then spread ideas to other people through interpersonal means of communication (Katz & Lazarsfeld 1955). The process of diffusing innovation or new ideas through a population is based on the finding that the adoption of new behaviours typically follows an S-shaped trajectory (Rogers & Scott 1997). There is usually a slow initial uptake followed by rapid acceptance, as opinion leaders or early adopters (who are usually from higher socioeconomic groups) communicate the benefits, and then a final slowing as a minority (who tend to be from isolated traditional communities) resist acceptance or change. This suggests that the mass media may be important in raising awareness and communicating basic information, but interpersonal sources, such as friends, peers and known ‘experts’, are most influential in persuading people to make changes.

Cultural effects

This model sees the media as having a key role in creating beliefs and values about health, medicine, disease and illness. The ways in which these are presented, from the kindly doctor in soap operas, to news bulletins on miracle cures and high-tech interventions, all contribute to people’s understanding of health (see, for example, Lupton 1994). Many studies use discourse analysis to reveal the underlying values, concepts and messages implicit in media portrayals of health and ill health. For example, Joffe & Haarhoff (2002) analyse the ways in which diseases such as Ebola are presented as deadly uncontrollable viruses whilst simultaneously giving the message that such diseases pose little threat to the UK. Harrabin et al (2003) argue that public health is neglected in the media. Public health’s long timescale and basis in numerical data make it unattractive to the mass media. Instead, ‘shock horror’ stories of crisis within the National Health Service (NHS) or the appearance of rare diseases tend to dominate the news headlines.

Does the media coverage you monitored fit into these categories?

Which categories were least/most common? What are the implications of this?

How much of the coverage was in entertainment programmes?

Think about and find some examples of how the following are represented in popular media culture:

Communication is concerned with the transmission of messages from a sender to a receiver. Messages are coded into signs and symbols which have meaning within specific codes. The message is encoded by the sender, and decoded by the receiver (Figure 12.2). The intention is that messages should be decoded and understood according to the intentions of the sender, but this can be problematic when using the mass media. This is because the mass media targets large audiences simultaneously, and, unlike direct personal communication, there is typically no feedback loop from the receiver back to the sender of the message. This means messages may be interpreted in ways that were not anticipated or intended by the sender. This is one reason why researching the target audience and piloting messages is an important stage in the planned use of the mass media for health promotion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

BOX 12.1

BOX 12.1 BOX 12.2

BOX 12.2

BOX 12.3

BOX 12.3 BOX 12.4

BOX 12.4 BOX 12.5

BOX 12.5