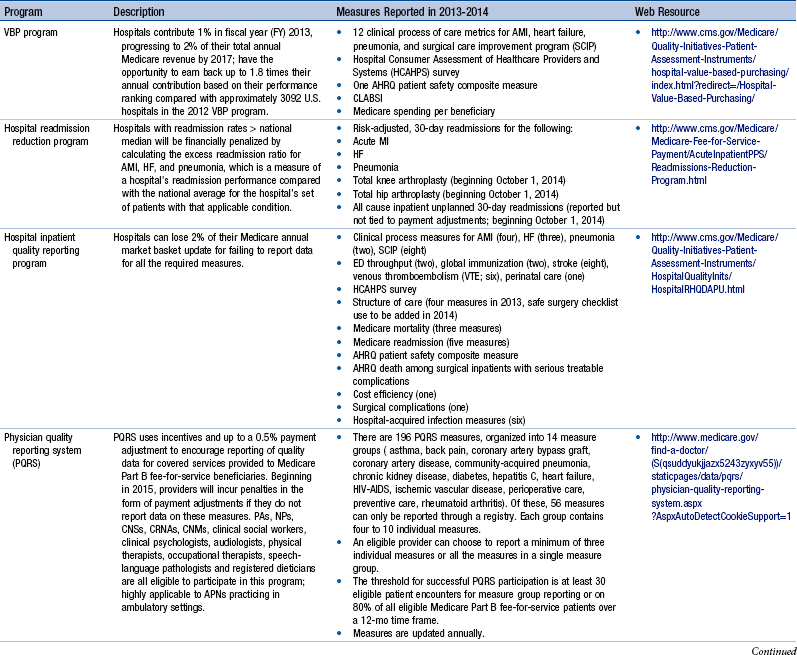

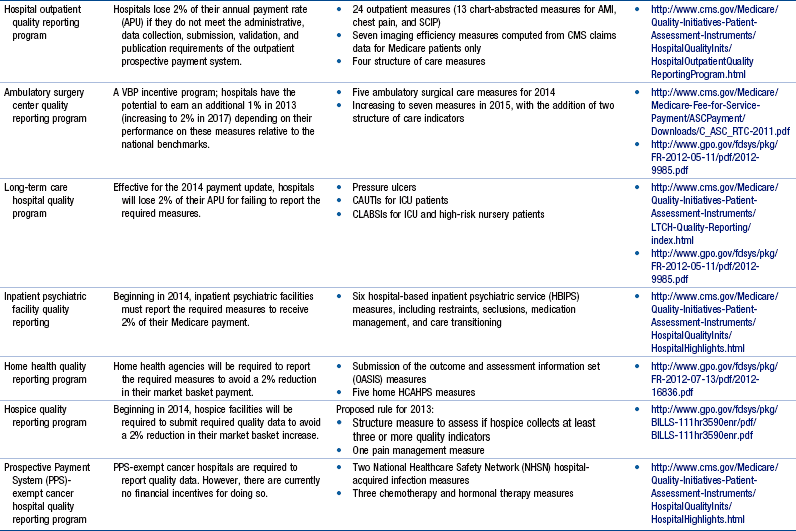

Chapter 24 Regulatory Reporting Initiatives That Drive Performance Improvement, 646 Relevance of Regulatory Reporting to Advanced Practice Nursing Outcomes Foundational Competencies in Managing Health Information Technology TIGER Competencies for Use of Health Care Information Technology Coding Taxonomies and Classification Systems Next-Generation Quality Metrics: eMeasures Meaningful Use of Health Information Technology and Impact on Advanced Practice Nursing Foundational Competencies in Quality Improvement Continuous Quality Improvement Frameworks Organizational Structures and Cultures That Optimize Performance Improvement Strategies for Designing Quality Improvement and Outcome Evaluation Plans for Advanced Practice Nursing The health care reform debate of this decade has generated countless hours of discussion on what the U.S. health care system will look like and how it will be paid for. Even with major steps forward, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011) and the creation of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation, which is designed to stimulate new ways to pay for and deliver care (http://innovations.cms.gov), there is little agreement on which health care models will best achieve measureable progress on the challenges of cost and quality. Innovating health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Health Care, the Mayo Clinic, Geisinger Health System, and Bellin Health, are already taking action to achieve what the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) calls the Triple Aim. These three imperatives aim to do the following: (1) provide effective, safe, and reliable care to individuals; (2) improve the health of populations by focusing on prevention, wellness, and improved management of chronic disease; and (3) decrease per capita costs. (For an informative discussion on health care system innovation strategies in the United States, the reader is referred to Bisognano & Kenney, 2012). Among the many options available to promote these goals, one stands out—wider deployment of and expanded practice parameters for advanced practice nurses (APNs). There is a fundamental fit between these national imperatives and the skills and expertise of each APN role. However, there are impediments in the regulatory environment that may place barriers to the full deployment of APNs. In a recent white paper published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011), The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, Safriet (2011) noted that there are “conflicting and restrictive state provisions governing [APNs] scope of practice and prescriptive authority … as well as the fragmented and parsimonious state and federal standards for their reimbursement” (p. 2). Numerous examples are cited, in which APNs may not examine and certify patients for worker’s compensation, order treatment for long-term care, or even make declarations of death. Extreme limitations in prescriptive authority exist in many states, as well as constraints for ordering durable medical equipment, physical therapy, or laboratory tests. Although Safriet (2011) has provided a comprehensive review of the many restrictions and limitations on APN practice and offers an array of arguments for reforming these regulatory restrictions, expanding APN practice autonomy and allowing for direct reimbursement, one thing is clear—the ability to demonstrate in a reliable and quantifiable manner that quality and cost-effective care can be consistently delivered by APNs is essential. Not only is this information needed to reform regulatory restrictions, it is needed by health care organizations to promote broader adoption and optimization of APN professional services in their emerging health care delivery models. Finally, this information is needed by the public to help raise awareness that APNs can deliver quality care in cost-effective ways. This means that it is every APN’s responsibility to engage fully in meaningful evaluative activities that will inform all stakeholders, including other APNs, about their effectiveness. In addition to the regulatory environment that affects APN practice, there is also a dynamic and ever-changing regulatory environment to which health care organizations must respond. In the United States, legislative requirements are being released by the CMS or HHS and posted in the Federal Registry numerous times each year. With each new posting, expanding reporting requirements are imposed on almost every point of service across the health care continuum. Although these reporting requirements are generally presented in the spirit of improving quality and patient safety, requirements for reporting quality data are increasingly being tied to financial reimbursement. Reimbursement for Medicare and Medicaid claims can be reduced for excessive readmissions, hospital-acquired infections and complications, substandard performance in evidence-based best practices, and decreased patient satisfaction scores. In postacute care settings there are emerging reporting requirements to monitor worsening of pressure ulcers, catheter-acquired urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), central line–associated blood stream infections (CLABSIs), and vaccination of health care personnel for influenza. The United States has truly evolved from a pay for reporting culture to one of pay for performance. Table 24-1 provides a summary of these reporting programs, along with a brief description of their impact on Medicare reimbursement. Some measures, such as CLABSI, not only apply to multiple quality reporting programs in a single health care facility, they also apply to multiple care settings across the continuum, including acute care hospitals, cancer care hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, and long-term care facilities. Thus, failure to comply with reporting requirements has the potential to affect reimbursement across an entire health care system. Additional measurement and reporting requirements for specialized services and health care systems also exist. Box 24-1 illustrates a recent set of measures that are required for health care systems reorganizing as accountable care organizations (ACOs). These measures focus on ambulatory populations and may overlap with several other reporting programs that exist simultaneously across an integrated health care organization, such as the measures required by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) for federal qualified health centers (see Box 24-2) or those required by providers who care for patients within selected payer niches, such as the Medicaid Adult Quality Measures Program (Box 24-3). In addition to payer-mandated reporting programs, health care organizations also have specific reporting requirements to their accreditation bodies, including The Joint Commission (TJC), Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program (HFAP), and Det Norske Veritas Healthcare (DNV). It is not unusual for many of the measures required for accreditation to overlap with those reported to the CMS, although these measures typically reflect an all-payer population. What is important to note is that although many of these measures are similar across reporting programs, each program has its own specific requirements for data collection, data quality, and data submission, which must be strictly adhered to in order to ensure proper accreditation, achieve financial incentives, or avoid financial penalties. APNs should become familiar with the regulatory reporting requirements in their organization, recognizing that some measures may merit higher degrees of APN engagement and stewardship to create and sustain optimal results. The National Quality Forum (NQF) Community Tool to Align Measurement is a useful tool for the APN to review so he or she can become familiar with the measures required for his or her practice setting. This tool organizes NQF-endorsed clinical quality measures associated with major national and state reporting initiatives for all practice settings into a single spreadsheet, which can then be sorted by various programs of interest. Hyperlinks are embedded in the spreadsheet so that it is easy to access the Quality Positioning System on the NQF website, on which measure definitions for each metric are maintained (http://www.qualityforum.org/AlignmentTool). Finally, additional regulatory reporting requirements are beginning to emerge in the areas of patient safety, an area in which APNs will likely become engaged. The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 established a voluntary patient safety event reporting system and guidelines for the establishment of patient safety organizations (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2005). This act called for the standardization of data used for event reporting based on the common formats established and maintained by AHRQ. Some of the initial risk events being reported include medication errors, patient falls, central line infections, and pressure ulcers. At the time of this writing, the NQF is proposing to include the reporting of readmissions data into patient safety organizations (PSOs) for purposes of shared learning across organizations. Although these emerging reporting requirements have not yet been adopted internationally, they are originally based on an international movement through the World Health Organization (WHO), which adopted a framework for an International Classification for Patient Safety to compare patient safety across disciplines and organizations and examine the roles of system and human factors in patient safety (WHO, 2009). The longitudinal work of the WHO is to develop an international classification system of codes that can be used to track patient safety events and the contributing factors leading up to the adverse event. APNs can play a critical role in identifying potential safety issues and developing priorities and safety solutions across all care delivery settings. Although APNs directly engage with these technologies at various levels, not all APNs are able to manipulate independently the various HIS needed to compile the data required to evaluate outcomes. More advanced skills from nurse informatics specialists or other expert report writers may be needed to capture necessary information, such as creating a customized report or merging files from multiple databases to assemble the required information. However, stronger informatics competencies in HIT are needed by APNs to design the evaluation strategy, validate the data, and interpret the findings effectively. For APNs prepared at the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) level, the expectation is that the APN is prepared to “apply new knowledge, manage individual and aggregate level information, and assess the efficacy of patient care technology appropriate to a specialized area of practice” (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006, p. 12). DNP graduates also design, select, and use information systems technology to evaluate programs of care, outcomes of care, and care systems. The expectations for being fluent in the use of technology are reflected in almost every DNP competency (AACN, 2006). The third competency involves information management, which is the underlying concept for performance measurement. This involves the process of collecting data, processing data, and presenting and communicating the processed data as meaningful information or knowledge. In addition, APNs must understand and comply with their organization’s Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) policies and procedures, which provide for how and when patient protected health information (PHI) may be used and under what circumstances it must be de-identified (meaning the removal of any unique patient identifiers, such as name, birth date, medical record numbers, social security numbers, and other personal information that could potentially identify specific individuals within a data set). Breaches of information, such as an unintentional disclosure of PHI in an unencrypted e-mail or a stolen laptop or device with PHI on it, must be immediately reported to the organization’s compliance officer; this can result in financial fines and legal consequences for the health care organization. Box 24-4 lists resources for obtaining additional information about the TIGER competencies. Although most health care organizations have quality management departments with the expertise to build an outcome evaluation plan and conduct the actual data collection and reporting tasks, the APN should understand these concepts to participate in, and in some cases lead, performance measurement activities actively throughout the full data-information-knowledge continuum. Without these competencies and skill sets, APNs may find that their level of participation is often limited to routine data collection tasks that do not require critical thinking or clinical judgment. APNs should limit participation in direct data collection activities unless it is part of their professional peer review process or if the data collection process is integrated into direct patient care and clinical documentation activities. For example, the minimum data set (MDS) used in long-term care settings to capture quality indicators relating to pressure ulcers, CAUTI and CLABSI, are routinely collected from retrospective data and do not require an APN’s time to abstract records and prepare reports. Rather, APNs should be validating the accuracy of the data, monitoring performance trends, and ensuring that best practices are implemented and fully adopted by the interdisciplinary team. Exemplar 24-1 illustrates a scenario of appropriate APN engagement with data collection activities associated with a professional peer review process for the purposes of outcome evaluation and performance improvement. Finally, it may be useful for APNs to understand other types of coding taxonomies and terminology sets that are available for purposes of quality reporting and research. Table 24-2 summarizes several common taxonomies used in inpatient and ambulatory settings. Coding Taxonomies and Terminology Sets Commonly Used in Outcomes Evaluation Although it is not necessary for the APN to understand the precision behind the coding processes, it is highly recommended that APNs spend time shadowing with a medical records coder (also referred to as a health information management specialist) to understand the timing and manner in which the various terminology sets are used. This is important to outcomes evaluation because some types of data are more useful than others, even though they represent similar concepts. For example, the phenomenon of pneumonia could be captured from the claim (using an ICD-9 diagnosis or CPT-4 code), laboratory culture and sensitivity report (using Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes [LOINC] and RxNorm codes), problem list in the EHR (using SNOMED-CT codes), chest imaging report (using natural language processing), or a dictated history and physical report (requiring manual chart abstraction). Although each source of information in the EHR may be correct, the APN may have to determine the best source of information to address the nature of the inquiry in the most timely, efficient, and accurate manner. Exemplar 24-2 illustrates the critical evaluation of the various data types that an APN would conduct when planning to deploy a new strategy to improve care, as well as the collaborative process with quality and informatics specialists that will benefit the APN in the outcome evaluation efforts.

Using Health Care Information Technology to Evaluate and Improve Performance and Patient Outcomes

Regulatory Reporting Initiatives that Drive Performance Improvement

![]() TABLE 24-1

TABLE 24-1

Foundational Competencies in Managing Health Information Technology

TIGER Competencies for Use of Health Care Information Technology

Coding Taxonomies and Classification Systems

![]() TABLE 24-2

TABLE 24-2

Coding Taxonomy

Description

Website

ICD-9-CM: ICD, version 9, clinical modification diagnosis codes

Approximately 13,000 codes three to five characters in length

Used primarily in the United States and United Arab Emirates (UAE) to classify diagnoses for inpatient hospital claims

Coding set lacks detail and laterality.

Limited space for adding new codes

United States targeted to sunset ICD-9 diagnosis codes October 1, 2014.

www.cms.gov/ICD9

ICD-9 procedure codes: ICD, version 9, procedure codes

Approximately 3,000 codes three or four characters in length

Used primarily in the United States to classify diagnoses for inpatient hospital claims

Coding set lacks detail and laterality

Lacks precision to define procedures adequately. Based on outdated technology

United States targeted to sunset ICD-9 procedure codes October 1, 2014.

www.cms.gov/ICD9

ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes: ICD, version 10, clinical modification diagnosis codes

Approximately 68,000 available codes three to seven alphanumeric characters in length

Used by most countries worldwide (United States targeted for transition in 2014) to classify diagnoses for inpatient hospital claims

Coding set is very specific and contains laterality.

Flexible for adding new codes

www.cms.gov/ICD10

ICD-10 procedure codes: ICD, version 10, procedure codes

Approximately 87,000 available codes seven alphanumeric characters in length

Used by most countries worldwide except the United States and UAE (United States targeted for transition in 2013) to classify procedures for inpatient hospital claims

Coding set very specific, provides for precisely defined procedures and laterality.

www.cms.gov/ICD10

CPT (current procedural terminology)

Approximately 7800 available codes for reporting medical, surgical, and diagnostic services in outpatient and office settings, as well as acute care emergency settings, ambulatory surgery, and inpatient procedures done in some hospitals outside the United States.

CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association and is considered a proprietary terminology set requiring licensure before using inside an HIT application.

New codes are released each October.

www.ama-assn.org/med-sci/cpt

HCPCS: Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System

There are two types of HCPCS codes. Level 1 HCPCS codes are identical to CPT codes used for reporting services and procedures in outpatient and office settings to Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurers. Level II HCPCS codes are used by medical suppliers other than physicians, such as ambulance services or durable medical equipment.

www.cms.gov/HCPCSReleaseCodeSets

SNOMED-CT

Complex and highly hierarchical collection of over a million codes and medical terms that describe diseases, procedures, symptoms, findings, and more

Developed by the College of American Pathologists and the National Health Service (Britain)

Used extensively throughout the world, SNOMED-CT codes help organize content in the EHR and cross-walk to other terminologies such as ICD-9, ICD-10, and LOINC.

www.snomed.org

LOINC

Universal standard containing 58,000 observation terms for identifying medical laboratory tests and clinical observations, as well as nursing diagnosis, nursing interventions, outcomes classification, and patient care data sets

Originally developed in the United States in 1994; international adoption expanding rapidly

http://loinc.org

RxNorm

Standardized nomenclature for clinical drugs produced by the National Library of Medicine. This data set is updated monthly to stay abreast of the rapidly changing pharmaceutical industry. It contains links between national drug codes, which are used widely in EHRs and e-prescribing systems.

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/rxnorm/docs/index.html

MS-DRGs

Each inpatient hospital stay in the United States is assigned one of over 750 MS-DRG codes, which are used for billing to Medicare and other payers. Codes are derived from ICD diagnoses and procedure codes. Many conditions are split into one, two, or three MS-DRGs based on whether any one of the secondary diagnoses has been categorized as a major complication or comorbidity (MCC), a CC, or no CC, and are weighted accordingly to reflect severity and reimbursement. Note that a separate MS-DRG code set for long-term care is used (MS-LTC-DRG). Additional coding sets apply to other areas of care (e.g., resource utilization groups [RUGs] apply to skilled nursing and rehabilitation stays).

www.cms.hhs.gov/AcuteInpatientPPS/FFD/list.asp

3M APR DRGs: (All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups)

Used predominately for illness severity and risk of mortality adjustments, this proprietary coding set is commonly used to disseminate comparative performance data for hospitals and providers. APR-DRGs are derived from ICD codes; inpatients are assigned one APR-DRG code, along with a severity of illness code (1-4) and a risk of mortality code (1-4). Although APR DRGs are used internationally, 3M also supports international refined (IR-DRGs), which apply to inpatient and outpatient populations. Additional 3M methods are available to assess and forecast longitudinal resource consumption for designated populations.

http://solutions.3m.com/wps/portal/3M

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Using Health Care Information Technology to Evaluate and Improve Performance and Patient Outcomes

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access